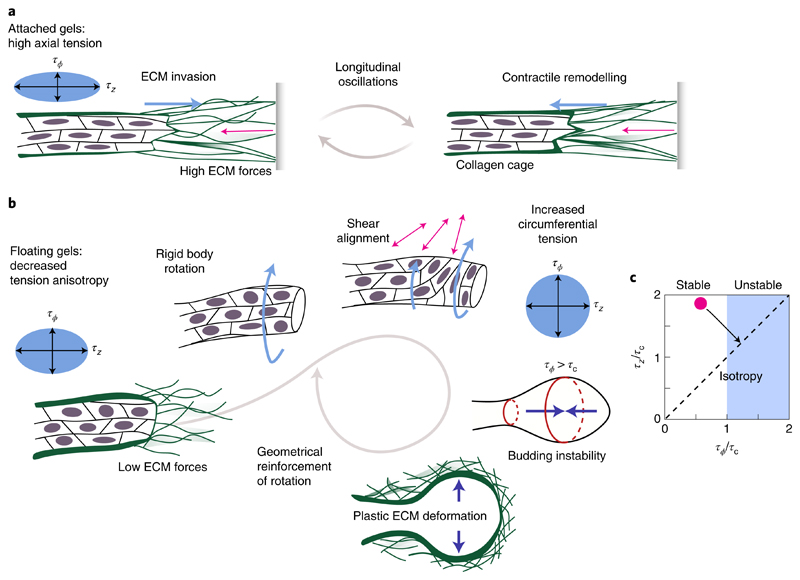

Fig. 4. A hydrodynamic model with anisotropic tension and ECM elasticity can explain the shape transition.

a, In attached gels, high ECM forces are balanced by anisotropic tension and cells move parallel to the branch axis. b, In floating gels, the onset of collective rotation is most likely a consequence of the decreased tension anisotropy, which is in agreement with flat epithelial dynamics28. The resulting surface shear aligns cells in the circumferential direction, increasing τϕ at the expense of τz. c, Stability analysis for a fluid cylinder surrounded by an elastic shell. The cylindrical shape becomes unstable for τϕ > τc ≃ Eh, where E and h correspond to the elastic modulus and thickness of the collagen cage, respectively. Through cell reorientations, the tissue can increase circumferential tension at the expense of axial tension, thus taking the initially stable cylindrical organoid (red dot) into the unstable regime (black arrow).