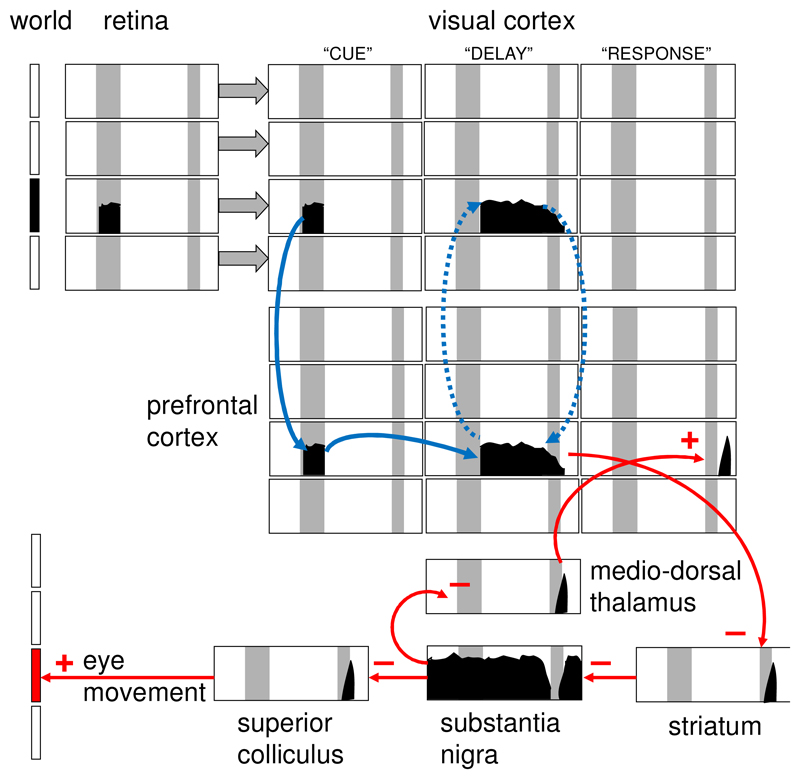

Figure 2.

Perception and action are intertwined in a cycle in mammals. They share their neural circuitry [130,131]. The will to act must start with a goal, which is usually marked by an external percept. The percept, itself, may be fleeting, but then prefrontal cortex uses iterative loops [132] to hold information in posterior cortex in the form of active memory [133]. The figure illustrates these general principles with a simple example based on a delayed response working-memory task in monkeys [132]. A target position is briefly indicated on a screen and registered by the retina (top left) which passes information to visual cortex, which in turn activates prefrontal cortex. During a delay interval, activity from prefrontal cortex refreshes visual cortex, keeping the stimulus location in active memory. When the end of the delay interval is signalled, this location is read out to circuits controlling eye movement and the monkey then looks at the position where the target was before the delay. Note that, unlike trace conditioning tasks, delay tasks do not depend on hippocampal circuitry. Figure adapted from [51] with permission.