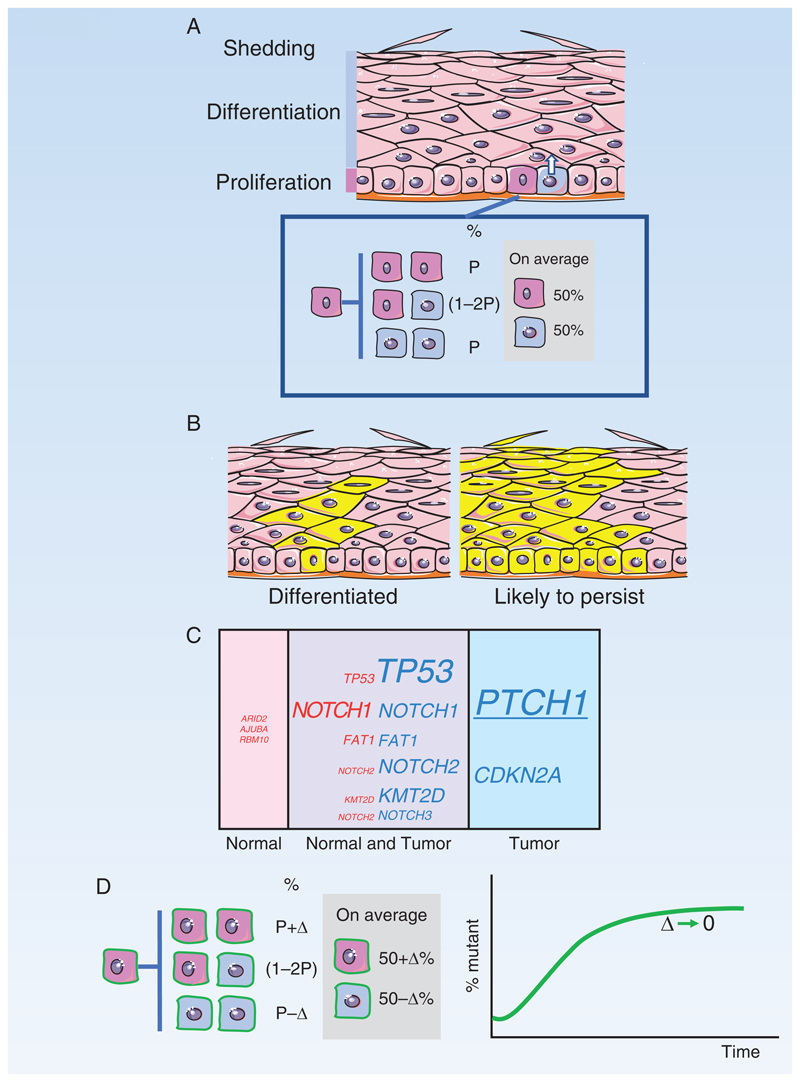

Figure 3. Epidermis.

A: Structure of the epidermis. Proliferating cells are confined to the basal cell layer. On commitment to differentiation, cells exit the basal layer and migrate to the surface. Division of a basal stem cell (dark pink) is coupled to the exit of an adjacent cell (blue) from the basal layer. Inset: Stem cell division results in two stem cells (pink), two differentiating cells (blue), or one cell of each type. The likelihoods of each division outcome (P) are balanced so that an average division generates 50% stem cells and 50% differentiating cells.

B: Typical outcomes of a neutral mutation in a stem cell (yellow). Most clones are lost by differentiation and shedding, after all basal layer cells differentiate (left hand panel). By chance, a few clones will become large and are likely to persist (right hand panel).

C: Mutant genes in normal epidermis and keratinocyte tumors

Percentage by area occupied by cells carrying mutant genes in epidermis of normal typical sun-exposed skin (pink) compared with percentage of tumors carrying mutants (blue). Mutations that appear in both normal skin and tumor are also indicated (purple). Font size indicates percentage. PTCH1, underlined, is only commonly selected in basal cell carcinoma.

D: Dynamics of Trp53 mutant clones in mouse epidermis

Induction of a missense dominant negative Trp53 mutation in single cells in mouse epidermis tilts the normal balance of stem cell fate towards proliferation, with the probability of divisions resulting in two stem cell daughters increasing by Δ above the likelihood of divisions producing two differentiating daughters. This increases the odds of mutant clones persisting rather than being lost by differentiation and produces an exponential increase in the proportion of Trp53 mutant cells in the epidermis. However, once areas of the epidermis have been colonized, the mutant cells within them revert towards balanced cell production (green curve, Δ decreases), so the tissue remains histologically normal and functional.