Abstract

Chirality typically arises in molecules because of a rigidly chiral arrangement of covalently bonded atoms. Less generally appreciated is that chirality can arise when molecules are threaded through one another to create a mechanical bond. For example, when two macrocycles with chemically distinct faces are joined to form a catenane, the structure is chiral although the rings themselves are not. However, enantiopure mechanically axially chiral catenanes in which the mechanical bond provides the sole source of stereochemistry have not been reported. We re-examined the symmetry properties of these molecules and in doing so identified a straightforward route to access them from simple chiral building blocks. Our analysis also led us to identify an analogous but previously unremarked upon rotaxane stereogenic unit, which also yielded to our co-conformational auxiliary approach. With methods to access mechanically axially chiral molecules in hand, their properties and applications can now be explored.

The term chiral was introduced by Lord Kelvin over a century ago to describe objects that are distinct from their own mirror image1. Chirality is relevant in many scientific areas2,3,4,5 but particularly chemistry because different mirror image forms of a molecule famously have different biological properties. Indeed, the shape of a molecule is a major determinant of its function6. Thus, chemists have invested significant effort to develop methods that produce molecules with control over their stereochemistry7. A major part of this effort, which has led to two Nobel prizes8,9, has focused on methods to selectively make molecules in one mirror image form because these are hard to separate using standard techniques. Although chirality is a whole-molecule property10, chemists often trace the appearance of molecular chirality back to one or more rigidly chiral arrangements of atoms in the structure. The most famous of these is the 'stereogenic centre' embodied by a tetrahedral carbon atom bonded to four different substituents, although stereogenic planes and axes are also found in important natural and synthetic structures. Chiral molecules containing such classical covalent stereogenic units have been studied extensively. Less explored are chiral molecules whose stereochemistry ar0ises absent any covalent stereogenic unit, such as Möbius ladders11, molecular knots12, and mechanically interlocked molecules13,14.

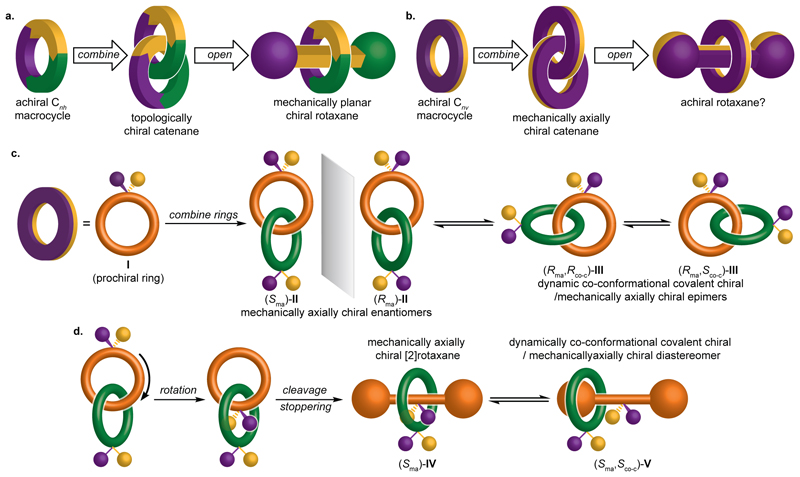

In 1961 Wasserman and Frisch identified that interlocked molecules called catenanes (two molecular rings joined like links in a chain) can display non-classical “mechanical” stereochemistry15; when both rings are 'oriented' (Cnh symmetry) a catenane exists in two mirror image forms (Fig. 1a). A decade later, Schill proposed that rotaxanes composed of an oriented ring encircling an axle whose ends are distinct are also chiral (Fig. 1a)16. In both cases, the sub-components that make up the interlocked structure are not themselves chiral, which is readily emphasized using commonly employed schematic representations that focus on the symmetry properties of the components (Fig. 1a). These representations also make clear that such topologically chiral catenanes and mechanically planar chiral rotaxanes are related notionally through ring opening. Although such molecules were initially challenging to make as single enantiomers17,18,19,20,21, recent efforts have allowed them to be accessed in good enantiopurity using standard synthetic approaches22,23,24,25,26,27.

Figure 1. Schematic depictions of the mechanical stereogenic units of chiral catenanes and rotaxanes (stereolabels are arbitrary).

(a) The mechanical topological and planar chiral stereogenic units of catenanes and rotaxanes are related by a notional ring opening process. (b) The minimal schematic representation of a mechanically axially chiral catenane suggests that there is no analogous axially chiral rotaxane. (c) Semi-structural representations of axially chiral catenanes reveal that such molecules can display co-conformational covalent chirality alongside the fixed mechanical stereogenic unit. (d) The semi-structural representation reveals that rotaxanes display a related but previously unrecognized form of stereochemistry.

Wasserman and Frisch also hinted at, but did not explicitly depict, a second form of catenane stereochemistry that arises when achiral rings with distinct faces (Cnv) are combined (Fig. 1b)15. In 2002, Puddephat and co-workers reported the first synthesis of such a mechanically axially chiral catenane as a racemate28,29. However, no enantiopure examples where the mechanical bond provides the sole source of stereochemistry have been disclosed to date30. To address this challenge, we re-examined the mechanical axial stereogenic unit of catenanes with a focus on not just the symmetry of the components but how this arises structurally. This led us not only to an efficient approach to enantiopure mechanically axially chiral catenanes but also to recognize and synthesize a noncanonical class of mechanically chiral rotaxanes that had previously been overlooked.

Results and discussion

Insights from semi-structural schematic representations

The minimal schematic representation of a mechanically axially chiral catenane (Fig. 1b) does not specify how the facial dissymmetry of the macrocycles arises. The most obvious way this can be achieved chemically is by including a prochiral unit in both rings (I, Fig. 1c)28,30. Strikingly, whereas the minimal schematic representation of a mechanically axially chiral catenane suggests there can be no rotaxane equivalent of this stereogenic unit (Fig. 1b), the semi-structural representation reveals that the notional ring opening process gives rise to a chiral rotaxane (Fig. 1d); even when the ring encircles the prochiral unit of the axle (IV) there is no representation that is achiral. Thus, we see that rotaxanes can display a previously unremarked upon noncanonical mechanically axially chiral stereogenic unit.

Building on the semi-structural analysis above, we returned to the general symmetry properties of mechanically axially chiral molecules. Whereas the components of catenane II and rotaxane IV have C1v point group symmetry, more generally mechanical axial stereochemistry will arise in catenanes whose rings have Cnv symmetry and rotaxanes whose axle has C1v symmetry (for an extended discussion see Supplementary section 13.1). Such structures will tend to exhibit prochirality31 – any single structural modification that does not lie on a symmetry plane will result in a chiral object (for an extended discussion see Supplementary section 13.2). As a direct consequence, although mechanically axially chiral molecules can always, in theory, adopt a highly symmetrical co-conformation (e.g. II and IV) that only expresses mechanical axial stereochemistry, if either ring is displaced from this arrangement the resulting structure contains both a mechanically axially chiral stereogenic unit and a co-conformational covalent stereogenic unit (e.g., III and V). These lower symmetry arrangements exist as pairs of co-conformational diastereomers and are an inherent property of mechanically axial chiral molecules (for an extended discussion see Supplementary section 13.3).

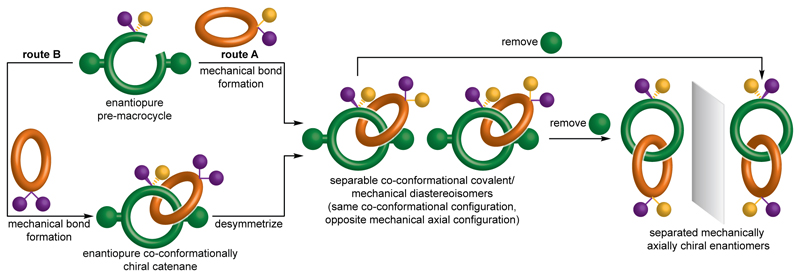

A co-conformational auxiliary approach to axially chiral catenanes and rotaxanes

Having recognized that co-conformational diastereoisomerism is a fundamental property of mechanically axially chiral molecules, it became obvious that a co-conformational stereogenic unit could act as a temporary source of chiral information in their synthesis (Fig. 2). By forming a mechanical bond selectively on one side of a prochiral unit (route A and designing the structure such that co-conformational exchange is initially blocked, the mechanically axially chiral catenane product would be formed as a pair of separable diastereomers with identical co-conformational configuration (here Rco-c) but opposite mechanical axial configuration (Rma or Sma). Alternatively, installing a facially symmetrical ring on one side of a prochiral center would give rise to a single co-conformational enantiomer (route B). Subsequent desymmetrization of the faces of the ring would give rise to the same pair of diastereomers. Removal of the groups preventing co-conformational motion would give mechanically axially chiral enantiomers in which the mechanical bond provides the sole fixed source of stereochemistry. An advantage of this co-conformational chiral auxiliary approaches is that co-conformational enantiomers can be made using chiral pool starting materials by choosing where the mechanical bond is formed17,32,33,34.

Figure 2. Proposed co-conformational auxiliary approach for the synthesis of axially chiral catenanes.

If the prochiral substituents and blocking groups are large enough to prevent co-conformational isomerism, the diastereomers can be separated and then converted into enantiomeric axially chiral catenanes.

To demonstrate our co-conformational auxiliary approach, (R)-serine was elaborated to pre-macrocycle (R)-1 (Supplementary section 2) (Fig. 3a). Macrocycle 2, which contains a prochiral sulfoxide, was readily synthesized (Supplementary section 3) using a Ni-mediated macrocyclization protocol35. Catenane formation was achieved by reacting (R)-1 with macrocycle 2 under active template36 Cu-mediated alkyne–azide cycloaddition (AT-CuAAC)37 conditions38 (route A Supplementary section 4.1); slow addition of (R)-1 to a solution of 2, [Cu(MeCN)4] and NiPr2Et in a mixture of CHCl3–EtOH gave catenanes 3, in which co-conformational motion is prevented by the bulky ester and N-Boc groups, as a separable mixture of diastereomers (d.r. = 71:29). A brief screen of reaction solvent did not allow us to identify conditions that enhanced the stereoselectivity of the reaction (Supplementary section 10.1). Catenanes 3 were also synthesised by reaction of (R)-1 with macrocycle 4 to give (Rco-c)-5 followed oxidation to give catenanes 3 (route B). The diastereoselectivity obtained depended strongly on the oxidant used (see Supplementary section 10.2). The maximum selectivity (39:61 d.r.) without significant over-oxidation was achieved when 2-iodoxybenzoic acid39 (IBX) was employed. Thus, under our optimal conditions, routes A and B proceeded with appreciable but opposite stereoselectivity. Single crystal x-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis of the major product of rac-1 and 2 allowed the different major stereoisomers produced in routes A and B to be assigned (Fig. 3c, Supplementary section 12.1).

Figure 3. Synthesis and analysis of enantiopure axially chiral catenane 6.

(a) Synthesis and separation of catenane diastereomers 3 from (R)-1 by route A or route B (Fig. 2) with opposite diastereoselectivity. Reagents and conditions: i. [Cu(MeCN)4]PF6, NiPr2Et, CH2Cl2, rt, 16 h; ii. IBX, NEt4Br, CHCl3-H2O (99 : 1), rt, 16 h. (b) Conversion of catenane 3 to enantiomeric catenanes 6. Reagents and conditions: CF3CO2H, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 1 h. (c) The solid-state structure of rac-(Sma,Rco-c)-3 allowed the major products of routes a and b to be assigned. (d) The solid-state structure of rac-6 contains rac-(Sma,Rco-c)-6 as the major co-conformational diastereomer. Analysis of (Rma)-6 (purple) and (Sma)-6 (orange) by (e) chiral-stationary-phase high-performance liquid chromatography and (f) circular dichroism spectroscopy respectively confirmed their enantiopurity and their chiral nature. IBX = 2-iodoxybenzoic acid. R = CO2Me.

Conversion of diastereomers 3 to structures in which the mechanically axially chiral stereogenic unit is the only fixed source of stereochemistry can be achieved by removing the Boc group (Fig. 3b and Supplementary section 5) or reducing the esters (Supplementary section 6). Accordingly, removal of the Boc group from (Rma,Rco-c)-3 or (Sma,Rco-c)-3 gave (Rma)-6 (>99% e.e.) and (Sma)-6 (>99% e.e.) respectively (Fig. 3e). The enantiomeric nature of these structures is supported by circular dichroism (CD) analysis (Fig. 3f). The solid-state structure of rac-6 (Fig. 3d) contains both co-conformational diastereomers with the rac-(Sma-Rco-c) co-conformation observed to dominate (~80:20, Supplementary section 12.2).

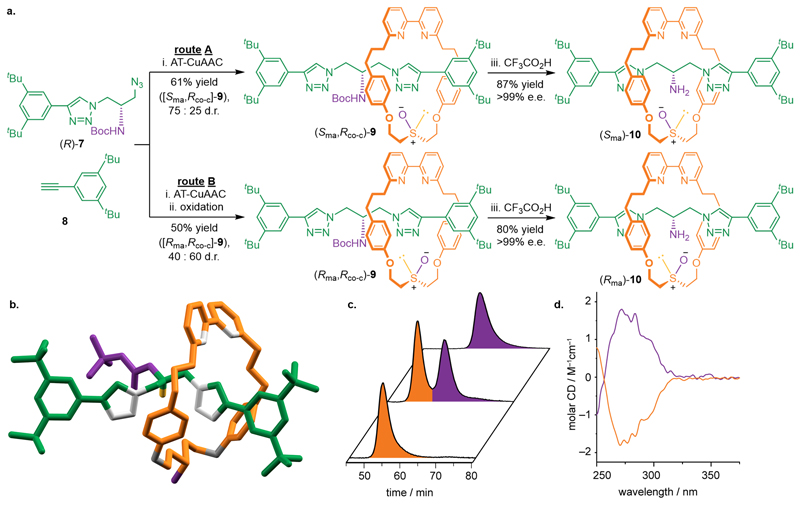

The same strategy was used to synthesize mechanically axially chiral rotaxane 10 (Fig. 4). Serine-derived azide (R)-7 (Supplementary section 7), alkyne 8 and macrocycle 2 were reacted under AT-CuAAC conditions40 to give a separable mixture (75:25 d.r.) of rotaxane diastereomers 9 (route A). Rotaxanes 9 could also be accessed by reaction of (R)-7, 8 and macrocycle 4 followed by oxidation (route B). As with catenanes 3, the diastereoselectivity of route B varied depending on the oxidant used (see Supplementary section 10.4) and the highest diastereoselectivity was obtained with IBX (40:60). SCXRD analysis (Supplementary section 12.4) of the major isomer obtained using route B with (R)-7 (Fig. 4b) allowed the major products of routes A and B to be assigned. Removal of the Boc group from separated samples of (Rma,Rco-c)-9 and (Sma,Rco-c) 9gave (Rma)-10 and (Sma)-10 respectively in excellent enantiopurity (>99% e.e., Fig. 4c). (Rma)-10 and (Sma)-10 produce mirror-image CD spectra (Fig. 4d) emphasizing the chiral nature of the new rotaxane mechanical axial stereogenic unit.

Figure 4. Synthesis of mechanically axially chiral rotaxane 10.

(a) Synthesis of diastereomeric mechanically axially chiral rotaxanes 9 by route A or B gives separable rotaxanes 9 that are converted to 10 by removal of the Boc group. Reagents and conditions: i. macrocycle 2 (route A) or macrocycle 4 (route B), [Cu(MeCN)4]PF6, NiPr2Et, CH2Cl2, rt, 16 h; ii. IBX, NEt4Br, CHCl3-H2O (99 : 1), rt, 16 h; iii. CF3CO2H, CH2Cl2, rt, 16 h. (b) SCXRD analysis of (Rma,Rco-c)-9allowed the major products of routes a and b to assigned. Analysis of (Rma)-10 (purple) and (Sma)-10 (orange) by (c) chiral-stationary-phase high-performance liquid chromatography and (d) circular dichroism spectroscopy respectively confirmed their enantiopurity and their chiral nature. IBX = 2-iodoxybenzoic acid.

Stereochemical assignment and properties of the mechanically axially chiral stereogenic unit

The assignment of the mechanically axially chiral stereogenic unit relies on identifying the highest priority faces of each ring, as proposed by Stoddart and Bruns13. However, because this rule had not been applied in a real system, we immediately encountered difficulties; to unambiguously assign the highest priority face of each ring the relative orientations of the prochiral units must be specified (for an extended discussion see Supplementary section 14.1). On reflection, we suggest that in the case of catenanes the in-plane substituents of the prochiral moieties be positioned at the extremities of the structure and oriented so they 'point' towards one another (Fig. 5a). Conversely, in the equivalent rotaxane, we suggest they be oriented to point in the same direction (Fig. 5b). The latter, somewhat counterintuitive, proposal is designed to ensure that a mechanically axially chiral rotaxane derived from the notional ring opening of an axially chiral catenane would retain the same stereolabel. The absolute stereochemistry of both mechanically axially chiral catenanes and rotaxanes can then be assigned by viewing the ensemble along the axis connecting the prochiral units and observing the relative orientation of the vectors from the out of plane substituent with the highest priority to the lowest priority as shown; a clockwise direction of rotation from the head of the front vector to the tail of the rear vector is assigned as Rma and an anticlockwise path assigned as Sma. This approach can be readily extended to molecules where facial dissymmetry arises due to prochiral stereogenic axes or planes (Supplementary section 14.2).

Figure 5. Assignment and further analysis of the mechanical axial stereogenic unit.

Methods to assign the stereogenic units of mechanically axially chiral (a) catenanes and (b) rotaxanes by specifying the relative orientation of prochiral moieties. (c) The two diastereomers identified in catenanes containing one prochiral and one fixed covalent stereogenic center. (d) The four diastereomers identified in catenanes containing a covalent stereogenic center in both rings whose structures can be specified using either a mechanical topological or axial stereodescriptor. (e) Selective symmetrization of the in-plane or out of plane substituents of one diastereomers of (d) gives a topologically or axially chiral catenane respectively. R = CO2Me.

Finally, we considered the stereochemical nature of catenanes in which one or both prochiral units are replaced with covalent stereocentres. Such structures represent logical alternative precursors to axially chiral catenanes if they could be prepared diastereoselectively and the in-plane substituents subsequently symmetrized. Furthermore, there has been a suggestion that the latter class might contain both mechanical axial and mechanical topological stereogenic units41. In the case of catenanes containing one stereogenic and one prochiral centre (Fig. 5c), ligand permutation analysis reveals two diastereomers (shown) and their enantiomers (i.e. four stereoisomers total), consistent with one covalent centre and one mechanical axial stereogenic unit (for an extended discussion see Supplementary section 15.1).

In the case of catenanes containing a stereogenic centre in each ring, ligand permutation reveals four diastereomers (Fig. 5d) and their enantiomers (eight stereoisomers total), consistent with two covalent and one mechanical stereogenic unit (for an extended discussion see Supplementary section 15.2). However, the nature of the mechanical stereochemistry is ambiguous; each structure can be assigned both a mechanical axial or a mechanical topological stereodescriptor, but only one of these is required to fully specify the structure. This analysis suggests that it would be incorrect to describe such catenanes as simultaneously topologically and mechanically axially chiral – one of the stereolabels would be redundant – but that it is unclear which description should take priority. Our preference would be to apply the mechanical topological stereodescriptor as this captures one of the interesting features of the system, that one of component of its stereochemistry is topologically invariant42. This analysis may appear philosophical in nature but has implications for the synthesis of chiral catenanes. If a single diastereomer of such a catenane could be isolated, it could be converted to an axially chiral catenane by selective symmetrization of the in-plane substituents, or a topologically chiral catenane by symmetrization of the out-of-plane substituents (Fig. 5e). This analysis further highlights that how a stereogenic unit is conceptualized can guide the development of new methodologies.

Conclusions

Detailed analysis of the symmetry properties of the mechanically axially chiral stereogenic unit of catenanes, and in particular the use of semi-structural representations, allowed us to identify an efficient co-conformational auxiliary approach to mechanically axially chiral catenanes and revealed a previously overlooked noncanonical axially chiral stereogenic unit in rotaxanes. The latter is a rare example of a 'new' source of stereoisomerism, as opposed to an overlooked pathway of isomer exchange43,44 or an overlooked opportunity for atropisomerism45, as have recently been reported. The rotaxane mechanical axial stereogenic is so closely related to that of catenanes it is surprising that it was overlooked for so long, which may in part be due to the use of schematic structures (Fig. 1b) that focus on symmetry without reference to underlying chemical structure; although these are useful, they can also obscure important chemical information. Indeed, given that the fixed mechanical stereogenic units of catenanes (topological and axial) now both have an equivalent in rotaxane structures (planar and axial), it appears sensible to suggest that the stereochemistry of rotaxanes and catenanes be unified rather than treated as separate as they are typically46.

Our analysis also led to the surprising conclusion that catenanes based on two rings each containing a single stereogenic center can be described as either mechanically topologically or axially chiral but that only one mechanical stereodescriptor is required to specify their structure, an observation with implications for future studies. Given the increasing interest in applications of chiral interlocked molecules47,48,49,50,51,34 including examples based on mechanical and co-conformationally chiral systems52,53,54, as well as other exotic or hard to access mechanical stereogenic units55,56,57,58,59,60, we anticipate these results will spur progress in the development of functional chiral interlocked systems61. Finally, it should be noted that dynamic stereochemistry related to that of mechanically axially chiral catenanes and rotaxanes can also arise due to conformational and co-conformational processes62,63, both of which have been observed but are poorly understood (for an extended discussion see Supplementary section 16). Such systems have potential applications as stereodynamic probes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

SMG thanks the ERC (Agreement no. 724987) and the Royal Society for a Wolfson Research Fellowship (RSWF\FT\180010). PB thanks the University of Southampton for a Presidential Scholarship. PRG thanks the university of Southampton for funding.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

JRJM and PRG contributed equally; both have the right to place themselves as first author on their CVs. JRJM and SMG developed the co-conformational auxiliary concept. JRJM synthesized 3 and 5 and collected SCXRD diffraction data for a reduced product of catenane 5. PRG synthesized 9 and 10, determined the stereochemistry of rotaxanes 9 and managed the preparation of manuscript graphics. DL optimized the synthesis and purification of 3, 5, synthesized 6 and determined the stereochemistry of catenanes 3. PB collected the X-ray diffraction data of 3, 6 and 9 and fully refined all SCXRD data. DL and PRG managed the preparation of the Supporting Information. SMG directed the research. All authors contributed to the analysis of the results and the writing of the manuscript.

Competing Interests Statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Availability Statement

All characterization data for novel compounds (NMR, MS, CD, HPLC) is available through the University of Southampton data repository (https://doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/D2185). Crystallographic data has been uploaded to the CCDC and is available under the accession numbers 2109976 (rac-(Sma,Rco-c)-3), 2115463 (rac-6), 2109991 (rac-S15) and 2109992 ((Rma,Rco-c)-9).

References

- (1).Kelvin WT. Baltimore Lectures on Molecular Dynamics and the Wave Theory of Light. C. J. Clay; London: 1904. p. 619. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Zschiesche D, et al. Chiral symmetries in nuclear physics. HNPS Proceedings. 2020;9 [Google Scholar]

- (3).Petitjean M. Symmetry, Antisymmetry, and Chirality: Use and Misuse of Terminology. Symmetry. 2021;13 [Google Scholar]

- (4).Mezey PG. Chirality Measures and Graph Representations. Comput Math Appl. 1997;34:105–112. [Google Scholar]

- (5).da Motta H. Chirality and neutrinos, a student first approach. J Phys Conf Ser. 2020;1558:012014 [Google Scholar]

- (6).Diaz DB, et al. Illuminating the dark conformational space of macrocycles using dominant rotors. Nat Chem. 2021;13:218–225. doi: 10.1038/s41557-020-00620-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Eliel EL, Wilen SH, Mander LN. Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds. John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- (8).The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2001 - NobelPrize.org. [accessed 9/11/2021].

- (9).The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2021 - NobelPrize.org. [accessed 9/11/2021].

- (10).Mislow K, Siegel J. Stereoisomerism and Local Chirality. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:3319–3328. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Herges R. Topology in chemistry: designing Mobius molecules. Chem Rev. 2006;106:4820–4842. doi: 10.1021/cr0505425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Fielden SDP, Leigh DA, Woltering SL. Molecular Knots. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:11166–11194. doi: 10.1002/anie.201702531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Bruns CJ, Stoddart JF. The Nature of the Mechanical Bond: From Molecules to Machines. Wiley; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Jamieson EMG, Modicom F, Goldup SM. Chirality in rotaxanes and catenanes. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47:5266–5311. doi: 10.1039/c8cs00097b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Frisch HL, Wasserman E. Chemical Topology. J Am Chem Soc. 1961;83:3789–3795. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Schill G. Catenanes, Rotaxanes and Knots. Academic Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Maynard JRJ, Goldup SM. Strategies for the Synthesis of Enantiopure Mechanically Chiral Molecules. Chem. 2020;6:1914–1932. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Chambron JC, Dietrich-Buchecker C, Rapenne G, Sauvage JP. Resolution of topologically chiral molecular objects. Chirality. 1998;10:125–133. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Yamamoto C, Okamoto Y, Schmidt T, Jager R, Vogtle F. Enantiomeric resolution of cycloenantiomeric rotaxane, topologically chiral catenane, and pretzel-shaped molecules: Observation of pronounced circular dichroism. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:10547–10548. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hirose K, et al. The Asymmetry is Derived from Mechanical Interlocking of Achiral Axle and Achiral Ring Components -Syntheses and Properties of Optically Pure [2]Rotaxanes. Symmetry. 2018;10:20. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Gaedke M, et al. Chiroptical inversion of a planar chiral redox-switchable rotaxane. Chem Sci. 2019;10:10003–10009. doi: 10.1039/c9sc03694f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Imayoshi A, et al. Enantioselective preparation of mechanically planar chiral rotaxanes by kinetic resolution strategy. Nat Commun. 2021;12:404. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20372-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Tian C, Fielden SDP, Perez-Saavedra B, Vitorica-Yrezabal IJ, Leigh DA. Single-Step Enantioselective Synthesis of Mechanically Planar Chiral [2]Rotaxanes Using a Chiral Leaving Group Strategy. J Am Chem Soc. 2020;142:9803–9808. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c03447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Bordoli RJ, Goldup SM. An efficient approach to mechanically planar chiral rotaxanes. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:4817–4820. doi: 10.1021/ja412715m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Jinks MA, et al. Stereoselective Synthesis of Mechanically Planar Chiral Rotaxanes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2018;57:14806–14810. doi: 10.1002/anie.201808990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).de Juan A, et al. A chiral interlocking auxiliary strategy for the synthesis of mechanically planar chiral rotaxanes. Nat Chem. 2022;14:179–187. doi: 10.1038/s41557-021-00825-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Denis M, Lewis JEM, Modicom F, Goldup SM. An Auxiliary Approach for the Stereoselective Synthesis of Topologically Chiral Catenanes. Chem. 2019;5:1512–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).McArdle CP, Van S, Jennings MC, Puddephatt RJ. Gold(I) macrocycles and topologically chiral [2]catenanes. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3959–3965. doi: 10.1021/ja012006+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Habermehl NC, Jennings MC, McArdle CP, Mohr F, Puddephatt RJ. Selectivity in the Self-Assembly of Organometallic Gold(I) Rings and [2]Catenanes. Organometallics. 2005;24:5004–5014. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Theil A, Mauve C, Adeline M-T, Marinetti A, Sauvage J-P. Phosphorus-Containing [2]Catenanes as an Example of Interlocking Chiral Structures. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:2104–2107. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).IUPAC. McNaught AD, Wilkinson A. In: the "Gold Book". 2nd. Chalk SJ, editor. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford; 1997. Compendium of Chemical Terminology. Online version (2019) ISBN 0-9678550-9-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Alvarez-Perez M, Goldup SM, Leigh DA, Slawin AM. A chemically-driven molecular information ratchet. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1836–1838. doi: 10.1021/ja7102394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Carlone A, Goldup SM, Lebrasseur N, Leigh DA, Wilson A. A three-compartment chemically-driven molecular information ratchet. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8321–8323. doi: 10.1021/ja302711z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Cakmak Y, Erbas-Cakmak S, Leigh DA. Asymmetric Catalysis with a Mechanically Point-Chiral Rotaxane. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:1749–1751. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Lewis JEM, et al. High yielding synthesis of 2,2’-bipyridine macrocycles, versatile intermediates in the synthesis of rotaxanes. Chem Sci. 2016;7:3154–3161. doi: 10.1039/c6sc00011h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Denis M, Goldup SM. The active template approach to interlocked molecules. Nat Rev Chem. 2017;1:0061 [Google Scholar]

- (37).Aucagne V, Hanni KD, Leigh DA, Lusby PJ, Walker DB. Catalytic ″click″ rotaxanes: a substoichiometric metal-template pathway to mechanically interlocked architectures. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2186–2187. doi: 10.1021/ja056903f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Lewis JEM, Modicom F, Goldup SM. Efficient Multicomponent Active Template Synthesis of Catenanes. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:4787–4791. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b01602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Shukla VG, Salgaonkar PD, Akamanchi KG. A mild, chemoselective oxidation of sulfides to sulfoxides using o-iodoxybenzoic acid and tetraethylammonium bromide as catalyst. J Org Chem. 2003;68:5422–5425. doi: 10.1021/jo034483b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Lahlali H, Jobe K, Watkinson M, Goldup SM. Macrocycle size matters: ″small″ functionalized rotaxanes in excellent yield using the CuAAC active template approach. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:4151–4155. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Schroder HV, Zhang Y, Link AJ. Dynamic covalent self-assembly of mechanically interlocked molecules solely made from peptides. Nat Chem. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41557-021-00770-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Walba DM. Topological Stereochemistry. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:3161–3212. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Canfield PJ, et al. A new fundamental type of conformational isomerism. Nat Chem. 2018;10:615–624. doi: 10.1038/s41557-018-0043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Canfield PJ, Govenlock LJ, Reimers J, Crossley MJ. Recent Advances in Stereochemistry Reveal Classification Shortcomings. ChemRxiv. 2020 This content is a preprint and has not been peer-reviewed. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Reisberg SH, et al. Total synthesis reveals atypical atropisomerism in a small-molecule natural product, tryptorubin A. Science. 2020;367:458–463. doi: 10.1126/science.aay9981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Lukin O, Godt A, Vogtle F. Residual topological isomerism of intertwined molecules. Chem Eur J. 2004;10:1878–1883. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Martinez-Cuezva A, Saura-Sanmartin A, Alajarin M, Berna J. Mechanically Interlocked Catalysts for Asymmetric Synthesis. ACS Catal. 2020;10:7719–7733. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Pairault N, Niemeyer J. Chiral Mechanically Interlocked Molecules - Applications of Rotaxanes, Catenanes and Molecular Knots in Stereoselective Chemosensing and Catalysis. Synlett. 2018;29:689–698. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Mitra R, Zhu H, Grimme S, Niemeyer J. Functional Mechanically Interlocked Molecules: Asymmetric Organocatalysis with a Catenated Bifunctional Bronsted Acid. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:11456–11459. doi: 10.1002/anie.201704647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Pairault N, et al. Heterobifunctional Rotaxanes for Asymmetric Catalysis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2020;59:5102–5107. doi: 10.1002/anie.201913781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Dommaschk M, Echavarren J, Leigh DA, Marcos V, Singleton TA. Dynamic Control of Chiral Space Through Local Symmetry Breaking in a Rotaxane Organocatalyst. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2019;58:14955–14958. doi: 10.1002/anie.201908330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Heard AW, Goldup SM. Synthesis of a Mechanically Planar Chiral Rotaxane Ligand for Enantioselective Catalysis. Chem. 2020;6:994–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Gaedke M, et al. Chiroptical inversion of a planar chiral redox-switchable rotaxane. Chem Sci. 2019;10:10003–10009. doi: 10.1039/c9sc03694f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Corra S, et al. Chemical On/Off Switching of Mechanically Planar Chirality and Chiral Anion Recognition in a [2]Rotaxane Molecular Shuttle. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:9129–9133. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b00941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Wood CS, Ronson TK, Belenguer AM, Holstein JJ, Nitschke JR. Two-stage directed self-assembly of a cyclic [3]catenane. Nat Chem. 2015;7:354–358. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Caprice K, et al. Diastereoselective Amplification of a Mechanically Chiral [2]Catenane. J Am Chem Soc. 2021;143:11957–11962. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c06557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Cui Z, Lu Y, Gao X, Feng HJ, Jin GX. Stereoselective Synthesis of a Topologically Chiral Solomon Link. J Am Chem Soc. 2020;142:13667–13671. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c05366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Carpenter JP, et al. Controlling the shape and chirality of an eight-crossing molecular knot. Chem. 2021;7:1534–1543. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Leigh DA, et al. Tying different knots in a molecular strand. Nature. 2020;584:562–568. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2614-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Corra S, de Vet C, Baroncini M, Credi A, Silvi S. Stereodynamics of E/Z isomerization in rotaxanes through mechanical shuttling and covalent bond rotation. Chem. 2021;7:2137–2150. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2021.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).David AHG, Stoddart JF. Chiroptical Properties of Mechanically Interlocked Molecules. Israel Journal of Chemistry. 2021;61:608–621. [Google Scholar]

- (62).Ashton PR, et al. Molecular meccano, part 23. Self-assembling cyclophanes and catenanes possessing elements of planar chirality. Chemistry-a European Journal. 1998;4:299–310. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Caprice K, et al. Diastereoselective Amplification of a Mechanically Chiral [2]Catenane. J Am Chem Soc. 2021;143:11957–11962. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c06557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All characterization data for novel compounds (NMR, MS, CD, HPLC) is available through the University of Southampton data repository (https://doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/D2185). Crystallographic data has been uploaded to the CCDC and is available under the accession numbers 2109976 (rac-(Sma,Rco-c)-3), 2115463 (rac-6), 2109991 (rac-S15) and 2109992 ((Rma,Rco-c)-9).