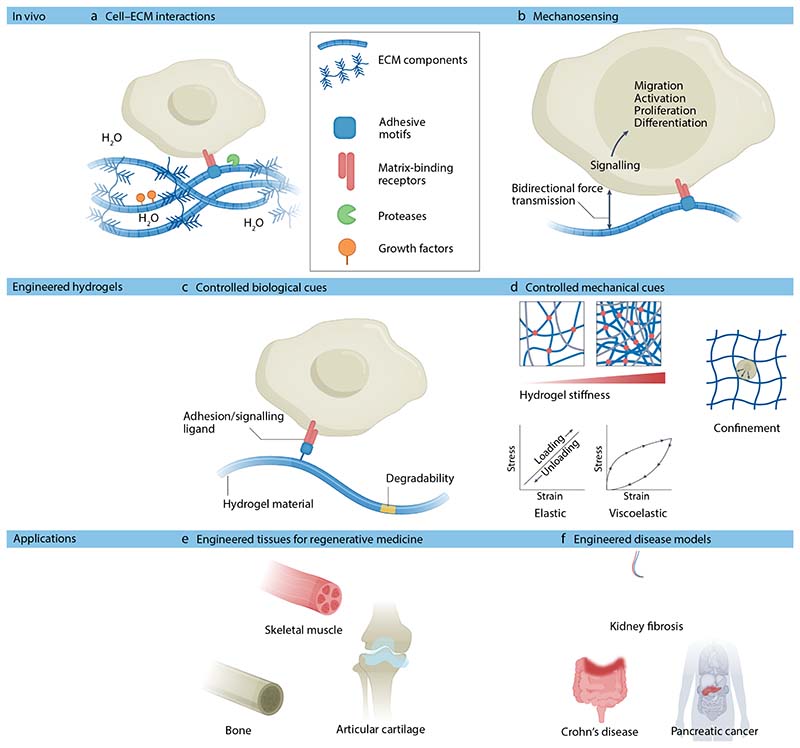

Figure 1. Engineered hydrogels replicate ECM and mechanical cues of native tissues.

a) In native tissues, cells interact with their surrounding ECM via matrix-binding receptors. b) Cells detect mechanical cues in their local environment by applying traction on their surrounding matrix. This process, known as mechanosensing, prompts biochemical signaling, which drives gene transcription and activation of various proteins resulting in cell migration, proliferation and progenitor cell differentiation. c) In vivo-like ECM cues can be replicated in hydrogels, often by tethering adhesive motifs copied from the native ECM directly into the hydrogel material. d) Many mechanical cues provided by the native environment can be replicated using hydrogels. For example, hydrogel properties can be modulated to mimic the stiffness or viscoelastic properties of a native tissue. Minimally deformable and non-degradable matrices can also be created to confine cells. e) Engineered hydrogels have found numerous applications in regenerative medicine and disease modelling. For example, as scaffolds for muscle, bone and cartilage tissue engineering. f) Hydrogels have also been applied in disease modelling to provide a local environment to cells and organoids that mimics tissue-specific ECM ligands and local elasticity/viscoelasticity. This approach enables mimicking of pathological changes in the native ECM during fibrotic wound healing and in diseases such as cancer. Abbreviations: ECM, extracellular matrix.