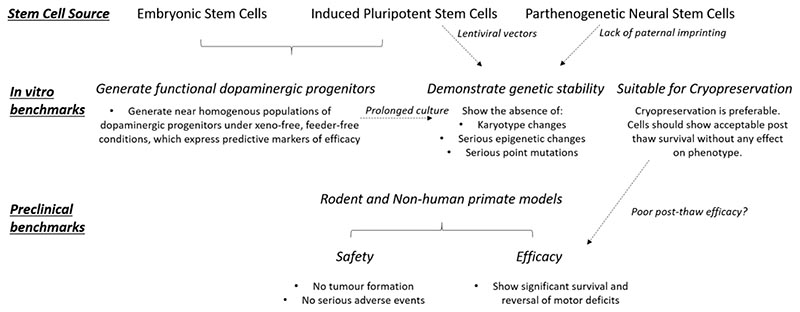

Fig. 2. Preclinical benchmarks of efficacy and safety required for a stem cell therapy for the treatment of PD to be considered for a clinical trial.

A first requirement is to be able to generate the cell type of choice (for the treatment of PD, A9 dopaminergic progenitors; top). When considering embryonic or induced pluripotent stem cells, the investigators must ensure that these can reliably generate sufficient numbers of functional dopaminergic progenitors expressing predictive markers of efficacy (middle left). All stem cell sources must demonstrate genetic stability. These can be defined as the absence of major changes in karyotype and the absence of epigenetic and/or point variants that could be implicated in relevant disease or in tumour formation (centre middle). It has been argued that, for induced pluripotent stem cells and parthenogenetic neural stem cells, the incidence of genetic aberrations may be increased owing to the use of lentiviral vectors and to the lack of paternal imprinting, respectively. If a stem cell therapy is to be widely used clinically, the ability to cryopreserve the product is preferable. However, cryopreservation must not have any detrimental impact on the viability, phenotype and/or functional efficacy of the cells, post-thaw. Because of the lack of relevant data, the risk of poor post-thaw survival and the effect of cryopreservation on cell phenotype require further investigation (middle right). At the preclinical-assessment stage, safety in cell grafting should be shown. Of upmost importance is that the grafts do not generate tumours; also, they should not result in any other serious adverse events, such as migration and integration into normal neural circuits. Moreover, the regulatory authorities require biodistribution and toxicity data for the cell product. Furthermore, for a product to be considered a viable clinical option, the grafted cells should be able to reverse motor dysfunction in a chemically lesioned rodent (and possibly in a non-human primate model) of PD, and this clinical benefit should be sustained (bottom). The dashed arrows indicate trade-offs between requirements.