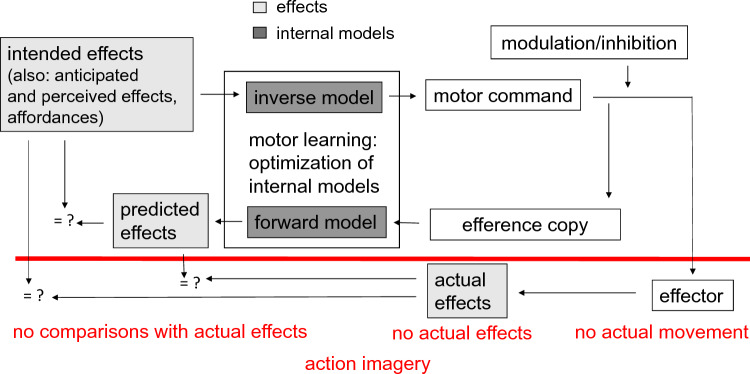

Fig. 1.

Model of action control (adapted and modified from Blakemore et al., 2002; Dahm & Rieger, 2019a, 2019b). Intended action effects (e.g., wanting to shoot the basketball into the basket), anticipated action effects (e.g., the expectation that the ball will set the net into motion when the ball passes through the net), perceived action effects (e.g., watching someone who shoots the ball into a basket), and affordances (e.g., seeing the basket) have the potential to activate the motor commands which usually lead to those effects or match the affordance of perceived objects using inverse models. After its activation, the motor command is sent to the effectors. Before it reaches the effector, some modulation or inhibition of the motor commands occurs, otherwise one would constantly react to affordances. Further, when a motor command is sent to the effectors, an efference copy is made. The efference copy is used by forward models to predict the consequences of the action on the body and on the environment (predicted effects). Three types of comparisons (indicated by = ?) can take place in executed actions to evaluate the appropriateness of an action and to detect errors: comparisons of intended and predicted effects, comparisons of actual and intended effects, and comparisons of actual and predicted effects. In action imagery, because no actual movement occurs, only the comparison between intended and predicted effects takes place. Motor learning is conceptualized as the acquisition of inverse and forwards models and their optimization, which results in successively lower discrepancies between intended, predicted and actual effects after repeated action execution