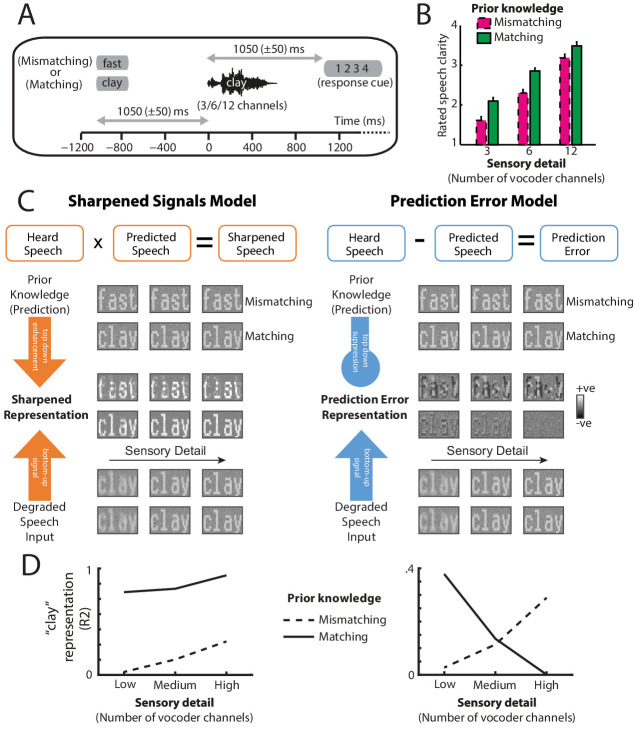

Figure 1. Overview of experimental design and hypotheses.

(A) On each trial, listeners heard and judged the clarity of a degraded spoken word. Listeners’ prior knowledge of speech content was manipulated by presenting matching (‘clay’) or mismatching (‘fast’) text before spoken words presented with varying levels of sensory detail (3/6/12-channel vocoded), panel reproduced from B, Sohoglu and Davis, 2016. (B) Ratings of speech clarity were enhanced not only by increasing sensory detail but also by prior knowledge from matching text (graph reproduced from Figure 2A, Sohoglu and Davis, 2016). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean after removing between-subject variance, suitable for repeated-measures comparisons (Loftus and Masson, 1994). (C) Schematic illustrations of two representational schemes by which prior knowledge and speech input are combined (for details, see Materials and methods section). For illustrative purposes, we depict degraded speech as visually degraded text. Under a sharpening scheme (left panels), neural representations of degraded sensory signals (bottom) are enhanced by matching prior knowledge (top) in the same way as perceptual outcomes are enhanced by prior knowledge. Under a prediction error scheme (right panels), neural representations of expected speech sounds are subtracted from sensory signals. These two schemes make different predictions for experiments that assess the content of neural representations when sensory detail and prior knowledge of speech are manipulated. (D) Theoretical predictions for sharpened signal (left) and prediction error (right) models. In a sharpened signal model, representations of the heard spoken word (e.g. ‘clay’; expressed as the squared correlation with a clear [noise-free] ‘clay’) are most accurately encoded in neural responses when increasing speech sensory detail and matching prior knowledge combine to enhance perception. Conversely, for models that represent prediction error, an interaction between sensory detail and prior knowledge is observed. For speech that mismatches with prior knowledge, increasing sensory detail results in better representation of the heard word ‘clay’ because bottom-up input remains unexplained. Conversely, for speech that matches prior knowledge, increased sensory detail results in worse encoding of ‘clay’ because bottom-up input is explained away. Note that while the overall magnitude of prediction error is always the smallest when expectations match with speech input (see Figure 1—figure supplement 1), the prediction error representation of matching ‘clay’ is enhanced for low-clarity speech and diminished for high-clarity speech. For explanation, see the Discussion section.

© 2016, PNAS

Figure 1A reproduced from Figure 1B, Sohoglu and Davis, 2016. The author(s) reserves the right after publication of the WORK by PNAS, to use all or part of the WORK in compilations or other publications of the author's own works, to use figures and tables created by them and contained in the WORK.

© 2016, PNAS

Figure 1B reproduced from Figure 2A, Sohoglu and Davis, 2016. The author(s) reserves the right after publication of the WORK by PNAS, to use all or part of the WORK in compilations or other publications of the author's own works, to use figures and tables created by them and contained in the WORK.

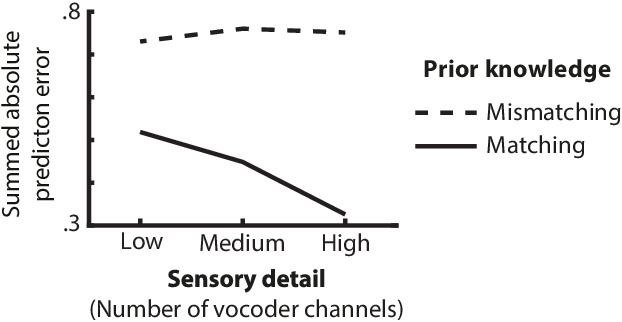

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Summed absolute prediction error for representations illustrated in Figure 1C.