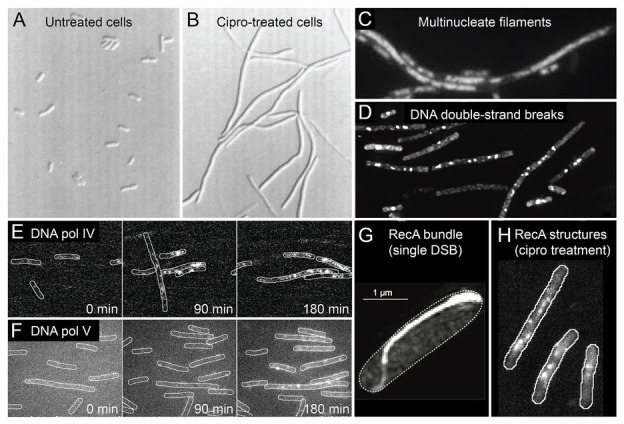

Figure 2.

Conditions inside bacterial cells undergoing antibiotic-induced mutagenesis. With the exception of panels (A) and (G), all panels depict Escherichia coli cells exposed to ciprofloxacin, a bactericidal antibiotic of the fluoroquinolones class. (A,B) E. coli growing as rod-shaped cells in the absence of antibiotics (A) and as filamentous cells in the presence of ciprofloxacin (B). Figure adapted from Diver and Wise (1986). (C) Filamentous E. coli cells contain multiple copies of the chromosome, as shown by DAPI staining. The number of chromosomes scales with filament length. Figure adapted from Bos et al. (2015). (D) Large numbers of DNA double-strand breaks in ciprofloxacin-treated cells, as detected by a fluorescent protein fusion of the Gam protein. Figure adapted from Pribis et al. (2019). (E,F) Increased activity of fluorescently labeled error-prone DNA polymerases IV (E) and V (F) in ciprofloxacin-treated cells, as visualized by single-molecule fluorescence microscopy. Figures adapted from Henrikus et al. (2018, 2020). (G) Large bundle of fluorescently labeled RecA formed in an E. coli cell that contains a single DNA double-strand break induced via expression of the SceI restriction enzyme. Figure adapted from Lesterlin et al. (2014). (H) Colocalisation of error-prone DNA polymerase IV with RecA in ciprofloxacin-treated cells. RecA-ssDNA nucleoprotein filaments (RecA*) are specifically visualized using a portion of the RecA*-binding cI repressor protein that has been fused to a fluorescent protein. Figure adapted from Henrikus et al. (2020).