Abstract

There has been a good deal of discussion in the literature regarding which subjects are vulnerable in the context of clinical trials. There has been significantly less discussion regarding when and how to include vulnerable subjects in clinical trials. This lack of guidance is a particular problem for trials covered by the US regulations, which mandate strict requirements on the inclusion of 3 groups: pregnant women/fetuses, prisoners, and children. For the past 30 years, funders, investigators, and institutional review boards have frequently responded to these regulations by excluding pregnant women/fetuses, prisoners, and children from clinical trials. More recent work has emphasized the extent to which a default of exclusion can undermine the value of clinical trials, especially pragmatic trials. A default of exclusion also has the potential to undermine the interests of vulnerable groups, in both the short and the long term. These concerns raise the need for guidance on how to satisfy existing US regulations, while minimizing their negative impact on the value of clinical trials and the interests of vulnerable groups. The present manuscript thus describes a six-step decision procedure that IRBs can use to determine when and how to include vulnerable subjects in clinical trials, including pragmatic trials, that are covered by US regulations.

Keywords: Vulnerable subjects, clinical trials, regulations

Background

US research regulations are based on the recommendations of the National Commission, which was charged with identifying ethical principles for research involving human subjects.1 The Commission was significantly influenced by the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, as well as the history of problematic research on prisoners, and the devastating impact of thalidomide on fetuses. Given this historical context, it is not surprising that the Commission’s recommendations tend to emphasize protecting subjects from the risks of research, as opposed to ensuring them access to its potential benefits.2

Based on these recommendations, US regulations place a range of conditions on clinical research and especially strict conditions on research with three groups: pregnant women/fetuses, prisoners, and children. Funders, investigators, and institutional review boards (IRBs) have frequently responded by excluding these groups. However, a default of exclusion can increase the costs and decrease the value of clinical trials. This is especially a problem for pragmatic trials, which attempt to assess existing approaches in real world settings. Moreover, it is now widely agreed that a default of exclusion has greater potential to set back, than it does to promote, the interests of vulnerable subjects themselves. With these concerns in mind, a number of groups have called for increasing the research participation of pregnant women, prisoners and children.3,4 To realize this goal, commentators argue that US regulations should be revised.5,6 Until they are, IRBs need guidance on how to satisfy existing US regulations, while minimizing their negative impact on the value of clinical trials and the interests of vulnerable groups.

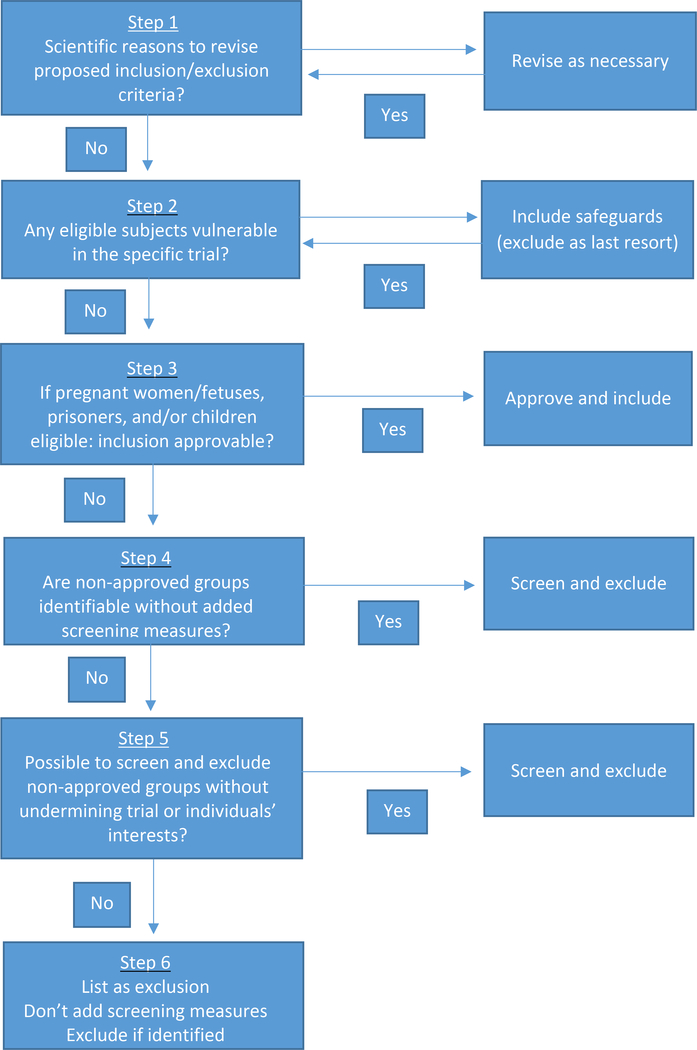

To address this need, the present manuscript proposes a six-step decision procedure on when and how to include vulnerable subjects in clinical trials (Figure 1). This procedure endorses a new approach to cases in which the participation of one or more groups is not approvable for regulatory reasons, but screening and excluding them would undermine the trial and/or the affected individuals’ interests. Specifically, it is argued that, in these cases, membership in the vulnerable group(s) should be listed as exclusion criteria and investigators should exclude individuals who are identified as members of these groups during the course of the research. However, IRBs should not mandate additional screening measures just to identify and exclude these individuals.

Figure 1.

Decision procedure for IRBs assessing when to include vulnerable subjects in clinical trials

Decision procedure for determining when and how to include vulnerable subjects

Step 1: Review proposed inclusion/exclusion criteria for scientific appropriateness

The first step involves the IRB reviewing, and amending as necessary, the inclusion/exclusion criteria proposed in the study. This step should assume a default of inclusion: groups should be included unless their participation would be scientifically inappropriate. For example, in this step, women should be excluded from studies assessing treatments for prostate cancer and teetotalers from studies assessing treatments for alcohol abuse disorder.

Step 2: Include protections for eligible individuals who are vulnerable

Once the IRB has determined that the inclusion/exclusion criteria are scientifically appropriate, it should evaluate whether any eligible individuals are vulnerable.7 This step includes, but is not limited to pregnant women, prisoners and children. If any eligible individuals are vulnerable, the IRB should mandate additional requirements to protect them. To make this assessment, the IRB should assess whether there are any eligible individuals for whom the requirements included in the study do not offer sufficient protection. For example, if the study collects sensitive information that might be disclosed to colleagues, being an employee can place individuals at increased risk. When it does, the IRB should ensure the study includes sufficient data protections. If it is not possible to protect employees’ confidentiality, the IRB should consider whether to exclude them. Because exclusion reduces the generalizability of trials, and can deny individuals access to trials that offer the potential for clinical benefit, individuals should be excluded only when it is not possible to protect them otherwise.

In some contexts, eligible individuals may be vulnerable to coercion or undue influence.8 When they are, US regulations mandate two additional steps: 1. Consideration of whether the IRB should include individuals who have knowledge and experience working with these subjects (46.107) and 2. Additional safeguards to protect their rights and welfare (46.111). These requirements give IRBs the flexibility to determine which safeguards make sense for a given trial. For example, whether employees may feel coerced to participate depends on their status within the organization and whether their superiors have an interest in their participation. When they do, the IRB might stipulate that consent should be obtained by someone who is not in the employee’s chain of command.

Given this flexibility, US regulations on research with individuals who may be vulnerable to coercion or undue influence typically can be satisfied without undermining the trial in question. US regulations on research with pregnant women/fetuses, prisoners, and children are stricter and, thus, pose a greater challenge. Steps 3–5 in the decision procedure are intended to address this challenge by helping IRBs to decide when and how to include these three groups in particular.

Step 3: Determine whether inclusion is approvable under US regulations

When steps 1 and 2 determine that pregnant women/fetuses, prisoners, and/or children are eligible, step 3 determines whether their inclusion is approvable under US regulations. When it is, the IRB should approve the inclusion of the relevant group(s) and they should be enrolled. Assuming any requirements needed to protect these individuals have been incorporated at step 2, there is no need for additional screening to identify which individuals are members of these groups, unless one of the goals of the study is to assess outcomes in these groups specifically.

Under existing US regulations, inclusion of pregnant women/fetuses, prisoners, and children is, unfortunately, not approvable for some trials, even when their participation raises no scientific or ethical concerns. Prisoners may be enrolled only when the IRB includes a prisoner representative (46.304) and the study is certified by the Secretary (46.306). In addition, studies that do not have “the intent and reasonable probability of improving the health or well-being of the subject” must be related to criminal behavior (46.306 2i), prisons (46.306 2ii) or conditions particularly affecting prisoners (46.306 2iii). Healthy children may be enrolled in studies that do not offer a potential for direct benefit only when the risks are no greater than minimal (46.404). US regulations on research with pregnant women are even stricter. To appreciate the extent to which existing regulations can pose an obstacle to clinical trials in general and pragmatic trials in particular, it will be helpful to consider these regulations in some detail.

US regulations permit the inclusion of pregnant women only when:

“Where scientifically appropriate, preclinical studies, including studies on pregnant animals, and clinical studies, including studies on nonpregnant women, have been conducted and provide data for assessing potential risks to pregnant women and fetuses” (45CFR46.204)

In some cases, such data may exist to assess the potential risks to pregnant women and fetuses. But, in many cases, these data will not exist, even though it would be scientifically appropriate to collect it. To consider one example, the TiME trial evaluated extended dialysis against usual care in patients with end-stage renal disease.9 Pregnancy in women who are on dialysis is increasingly common.10 This raises the possibility that the trial might end up including pregnant women. What risks the study poses to pregnant women and fetuses is thus a relevant question. And conducting a prior trial in nonpregnant women could provide data relevant to answering it. In addition, it seems clear that a prior trial could be designed in a way that is consistent with the norms of science, in which case it would be scientifically appropriate.

One might object that conducting a prior trial could substantially delay the TiME trial. Moreover, the value of the information it would collect seems unlikely to justify the costs. While that seems right, the regulations do not require prior trials when they would be valuable or interesting. The regulations mandate prior trials as long as they are scientifically appropriate. The fact that a prior trial may not collect information that is of sufficient value to justify its costs suggests it may be inappropriate on resource allocation grounds. But, it does not imply that it would be scientifically inappropriate.

US regulations also permit clinical trials to be approved for pregnant women only when:

“The risk to the fetus is caused solely by interventions or procedures that hold out the prospect of direct benefit for the woman or the fetus; or, if there is no such prospect of benefit, the risk to the fetus is not greater than minimal and the purpose of the research is the development of important biomedical knowledge which cannot be obtained by any other means.”

Many clinical trials satisfy these conditions. For example, trials involving fetal therapies typically offer a prospect of direct benefit to the fetus. However, many other trials do not. This is especially a problem for more pragmatic trials, which attempt to evaluate existing approaches in real world settings. Pragmatic trials frequently assess interventions that are available in the clinical context, in which case they do not offer a prospect of direct benefit beyond what is available outside of research. At least some of these trials do not pose any additional risks beyond those present in clinical care, suggesting that they may qualify as minimal risk. However, the purpose of these trials typically can be achieved without enrolling pregnant women.

To consider one example, the ABATE trial evaluated Chlorhexidine, routinely used in many ICUs, versus standard bathing for reducing infections in medical and surgical units.11 It was unknown whether participation offered a prospect of direct benefit. The trial did pose minimal risk. However, the purpose of the trial was to collect data regarding the use of Chlorhexidine in standard medical and surgical units. This goal could be achieved without the inclusion of pregnant women, suggesting that this could not be approved for the inclusion of pregnant women.

In response, one might suggest revising the purpose of the trial to include a systematic assessment of Chlorhexidine in pregnant women. That would make sense. However, realizing that goal would require the investigators to perform pregnancy testing on all women of child bearing potential to determine which ones are pregnant. This screening would substantially increase the costs of the trial and significantly undermine its pragmatic nature. Moreover, absent reason to think that the outcomes of bathing are likely to be different in pregnant women, these changes would offer no increase in the value of the data that could justify their costs.

Studies like this pose an important challenge. Steps 1 and 2 find that the inclusion of pregnant women/fetuses, prisoners, and children does not raise scientific or ethical concerns. However, step 3 determines that the participation of one or more of these groups is not approvable under existing regulations. And, revisions to the design of the study to satisfy the regulations would substantially increase its costs and undermine its value. How should IRBs proceed in these cases?

Step 4: Assess whether non-approvable groups are identifiable without added screening

Simply in the course of conducting clinical trials, investigators sometimes identify individuals as pregnant, prisoners or minors. When clinical trials are conducted in prisons, it typically is obvious which individuals are prisoners. Similarly, five year olds are clearly minors. And, during clinic visits, some women disclose that they are pregnant. If the study is not approvable for these groups, IRBs should mandate that they be excluded, even when their participation does not raise ethical or scientific concerns.

Step 5: Assess the impact of added screening and exclusion of non-approvable groups

Other individuals are not readily identifiable as belonging to a non-approvable group. For example, individuals who have been detained in a residential facility for substance abuse treatment qualify as prisoners.12 However, these individuals may not be readily identifiable as “prisoners”. Similarly, many teenagers are not obviously younger than 18. In some cases, mandating additional steps to identify and exclude these individuals raises minimal or no concern. For example, investigators often can simply ask potential participants whether they are under 18. In addition, explanatory trials typically have extensive inclusion/exclusion criteria, with targeted screening measures. Mandating additional screening measures, such as review of potential participants’ records to determine whether they are minors, adds relatively few costs and burdens to these trials. In these cases, IRBs should mandate the added screening and exclusion of individuals who are identified as belonging to a non-approvable group.

In other cases, mandating additional steps to identify and exclude individuals whose participation is not approvable can undermine the trial. It can increase the costs and undermine the extent to which more pragmatic trials are able to rely on real world settings. For example, pregnancy screening prior to bathing in the ABATE trial would be inconsistent with and significantly disruptive to standard care. Excluding vulnerable individuals also raises concern when it precludes them from accessing potentially beneficial treatments.

Step 6: Determine how to proceed when participation is not approvable, but screening and exclusion is problematic

Step 6 addresses cases where the relevant ethical and scientific considerations support the inclusion of vulnerable groups, but the regulations do not permit their inclusion. Given this conflict between ethics and science on the one hand, and the regulations on the other, no approach will be fully satisfactory. The question, then, is whether any approach, although not ideal, is better than the status quo which involves screening and exclusion to satisfy the regulations, despite the costs of doing so.

Interpret existing regulations liberally

Given that the existing regulations are outdated, one might argue that the best way to address conflicts between the regulations and the relevant ethical and scientific considerations is to interpret the regulations in whatever way is necessary to make them consistent with the ethical and scientific considerations. If the requirement that a study must address criminal behavior blocks appropriate inclusion of prisoners, IRBs might simply regard the study as addressing this issue. If the requirement to conduct prior studies in nonpregnant women blocks appropriate inclusion of pregnant women, IRBs might interpret the requirement to conduct such studies when they are scientifically appropriate as requiring the conduct of these studies when they are scientifically valuable.

The temptation to interpret the regulations in whatever ways the reviewing IRB regards as leading to ethically better outcomes, even when doing so goes against the clear meaning of the relevant terms, is understandable. But, widespread adoption of this approach would effectively eliminate the regulations and replace them with the judgement of individual IRBs. This approach could lead to significant abuses and erosion of public trust in clinical research. This approach thus seems worse than the status quo, which threatens individual trials, but not clinical research more generally.

Existing recommendations

Don’t screen, don’t exclude. Some authors, focusing on pragmatic trials, recommend that, absent a scientific or ethical reason to do otherwise, pregnant women/fetuses, prisoners, and children should not be excluded and individuals should not be screened to determine whether they belong to one or more of these groups.13,14 This approach has several advantages. It protects the ability of clinical trials to enroll representative populations and allows individuals to access the potential benefits of trials. It also avoids the need to add screening methods that might undermine trials simply to satisfy the regulations. Unfortunately, this approach forces some investigators to violate the regulations or the approved protocol.

The problem arises when investigators identify some individuals as pregnant, prisoners or minors simply in the course of conducting clinical trials. If the study does not satisfy the regulations on the inclusion of these individuals, allowing them to participate would violate the federal regulations. But, excluding them, in the absence of an explicit exclusion criterion, violates the approved protocol. Putting investigators in the position of having to violate the regulations or approved protocols seems worse than the status quo.

Present proposal: Don’t screen, exclude

The benefits of the existing recommendations trace to the suggestion that investigators not take extra measures to identify vulnerable subjects purely for the purposes of satisfying the regulations. The problems trace to the suggestion that membership in these groups not be listed as exclusion criteria. This suggests a better approach might be to maintain the recommendation of not mandating additional measures simply to identify these individuals, but to list membership in non-approvable groups as exclusion criteria. This approach avoids the need to include added screening tests that are not indicated for scientific or safety purposes and have the potential to undermine the trial and/or individuals’ interests. But, it permits investigators to exclude individuals who are identified as belonging to a group whose participation is not approved. It thereby avoids putting investigators in the position of having to violate the regulations or the approved protocol.

This approach has three important advantages. It helps to enhance the social value of research by increasing the extent to which trials can enroll representative patient populations and rely on real world settings. It also helps to reduce the burdens on participants by eliminating screening tests not needed for scientific or ethical reasons. Finally, by avoiding screening tests that are not needed for scientific or ethical reasons, this approach saves money and resources. These advantages suggest this approach may be better than the status quo.

Potential objections

The present proposal recommends the exclusion of individuals who are identified during the course of research as belonging to a group whose participation is not permitted under the regulations. It also recommends that IRBs mandate additional screening measures to identify and exclude these individuals when doing so will not undermine the trial or the affected individuals’ interests. In contrast, the present proposal recommends that IRBs not mandate additional screening measures when they are not needed for scientific or ethical reasons, and they would undermine the trial and/or the affected individuals’ interests.

One might object to this proposal on the grounds that it involves IRBs approving studies when they know that the screening measures will result in the participation of some ineligible individuals. While this is certainly not ideal, it is not problematic. Indeed, it is inevitable. In many cases, there are no screening measures which can identify with complete accuracy whether potential participants are eligible or ineligible. Examples include a history of heavy drinking, a history of attempted suicide, recent cocaine use, and recent participation in an experimental trial. In these cases, IRBs approve trials which rely on self-report to determine whether potential participants are eligible, even though it is known that self-report of these issues is frequently inaccurate. Similarly, there is no definitive screening test for many diseases, including Alzheimer disease, Fabry disease, Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Fibromyalgia, and Lime Disease. These examples illustrate that IRBs frequently do and should approve studies, even though they recognize that the screening methods are not sufficient to identify all ineligible individuals. The alternative of not approving these studies would halt a good deal of clinical research, including research on many important conditions and illnesses.

One might accept this practice when there are no screening measures that would be more accurate. In contrast, it might be argued that IRBs should always mandate the most accurate screening measures available to identify ineligible individuals. While this approach seems more reasonable, it too is problematic. Trials that are not approved for minors frequently rely on self-report, asking potential participants how old they are. These steps will identify many minors. However, it will miss minors who are motivated to enroll and willing to misstate their age. Similarly, standard practice for screening pregnant women is to perform urine pregnancy tests prior to enrollment and periodically during the course of the study. However, it is known that urine pregnancy tests miss very early-term pregnancies.

In these cases, IRBs approve studies when it is known that the screening measures will fail to identify some ineligible individuals and more accurate measures are available. In the case of minors, investigators could require photo identification with a birth date. Or, given the potential for fake identification, investigators could be required to review the records of each individual to determine their age. When a study is not approvable in pregnant women, investigators could be required to conduct daily urine screening or even use blood pregnancy testing, which is more sensitive than urine testing. When the participation of ineligible individuals raises significant concern, these added measures should be considered. In contrast, when their participation does not raise significant ethical or scientific concerns, it is appropriate for IRBs to not mandate these added measures, even when that approach will increase the number of participants whose inclusion is inconsistent with the regulations.

These examples illustrate a critical point. Existing and appropriate practice does not require investigators to take all possible steps to exclude individuals whose participation is inconsistent with the regulations. Instead, investigators should practice due diligence, taking all appropriate steps to screen out ineligible participants. Which screening tests are appropriate, and which ones are excessive, depends not simply on ensuring that individuals who are ineligible on regulatory grounds do not participate. It takes into account both the costs and the benefits of the available options. It is appropriate to use less than the most accurate screening measures when greater screening would pose costs that are not justified by the value of having fewer ineligible individuals participate. The present proposal is consistent with this practice. It recommends that IRBs not mandate added screening measures to identify ineligible individuals when their participation is acceptable on scientific and ethical grounds and the added screening and exclusion has the potential to undermine the trial and/or the affected individuals’ interests.

Summary

IRBs should assess the proposed inclusion/exclusion criteria of every study they review, determine whether any revisions are needed on scientific grounds, and then consider whether any eligible individuals are vulnerable. When they are, appropriate safeguards should be adopted to protect them. If the final inclusion/exclusion criteria permit the participation of pregnant women/fetuses, prisoners, and/or children, the reviewing IRB should assess whether their enrollment is approvable under existing US regulations. When it is, their participation should be approved.

When the participation of pregnant women/fetuses, prisoners, and/or children is not approvable under existing regulations, IRBs should assess whether they can be screened and excluded without undermining the trial or individuals’ interests. If so, they should be screened and excluded. These steps leave the challenge of what to do when the participation of pregnant women/fetuses, prisoners, and/or children does not raise scientific or ethical concerns and is not approvable under the regulations, but additional screening and exclusion would undermine the trial and/or set back the affected individuals’ interests.

I have argued that, in these cases, membership in these groups should be listed as an exclusion criterion. This permits investigators to exclude any individuals who are identified as ineligible. At the same time, IRBs should not mandate the addition of screening measures which are not justified on scientific or ethical grounds and which undermine the trial or individuals’ interests. This approach involves IRBs approving studies when it is known that the screening measures likely will permit some ineligible individuals to participate. While this approach is not ideal, it offers an improvement on the status quo of screening and excluding vulnerable groups simply in order to satisfy the regulations, even when doing so undermines the trial and/or the affected individuals’ interests.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Christine Grady, Joe Millum, Holly Taylor, and Ben Berkman for helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Funding/Disclaimer

The present work was funded by intramural funds of the NIH Clinical Center. However, the views expressed are the author’s own. They do not represent the position or the policy of the NIH or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Funding Information: There are no funders to report for this submission

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Belmont Report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research, https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/index.html (1979, accessed 23 April 2020). [PubMed]

- 2.Recommendations of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, https://bioethicsarchive.georgetown.edu/pcbe/reports/past_commissions/.

- 3.Lyerly AD, Little MO, and Faden R. The second wave: Toward responsible inclusion of pregnant women in research. Int J Fem Approaches Bioeth 2008; 1(2): 5–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Food and Drug Administration. Enhancing the diversity of clinical trial populations—eligibility criteria, enrollment practices, and trial designs. Guidance for industry, https://www.fda.gov/media/127712/download (2019, accessed 23 April 2020).

- 5.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Ethical Considerations for Revisions to DHHS Regulations for Protection of Prisoners Involved in Research. Ethical Considerations for Research Involving Prisoners. Editors: Gostin Lawrence O, Cori Vanchieri, and Andrew Pope. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; (US: ), 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elger BS and Spaulding A. Research on prisoners - a comparison between the IOM Committee recommendations (2006) and European regulations. Bioethics 2010; 24(1): 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kipnis K Seven vulnerabilities in the pediatric research subject. Theor Med Bioeth 2003; 24: 107–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Largent EA, Grady C, Miller FG, Wertheimer A. Money, coercion, and undue inducement: attitudes about payments to research participants. IRB 2012; 34(1): 1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UH3 Project: Time to reduce mortality in end-stage renal disease (TiME), https://rethinkingclinicaltrials.org/demonstration-projects/uh3-project-time-to-reduce-mortality-in-end-stage-renal-disease-time/ (Accessed 23 April 2020).

- 10.Piccoli GB, Minelli F, Versino E, et al. Pregnancy in dialysis patients in the new millennium: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis correlating dialysis schedules and pregnancy outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31: 1915–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang SS, Septimus E, Kleinman K, et al. Chlorhexidine versus routine bathing to prevent multidrug-resistant organisms and all-cause bloodstream infections in general medical and surgical units (ABATE Infection Trial): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2019; 393: 1205–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Office for Human Research Protections. Prisoner research FAQs, https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/faq/prisoner-research/index.html (Accessed 23 April 2020).

- 13.Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections. Attachment C: Recommendations on regulatory isues in cluster studies, March 13, 2014, http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sachrp-committee/recommendations/2014-july-3-letter-attachment-c/index.html (Accessed 23 April 2020).

- 14.Welch MJ, Lally R, Miller JE, et al. The ethics and regulatory landscape of including vulnerable populations in pragmatic clinical trials. Clin Trials 2015; 12: 503–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]