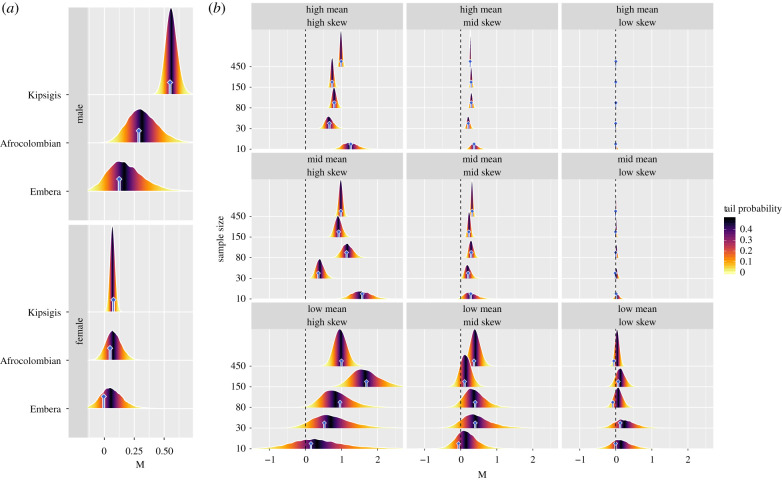

Figure 2.

Frame (a): point estimates (blue bars) and posterior estimates (density distributions) of M for males and females in three human populations with different marriage systems. For males, M distinguishes the polygynous Kipsigis from the serially monogamous Afrocolombians—a mean difference of 0.23 (90% CI: 0.01, 0.46)—and the monogamous Emberá—a mean difference of 0.32 (90% CI: 0.07, 0.58). However, despite male Afrocolombians and Emberá having fairly distinct point estimates of M, a Bayesian approach suggests that it is hard to reliably conclude that there are skew differences between these populations given the relevant sample sizes—i.e. we see a mean difference of 0.08 (90% CI: −0.23, 0.42), where the posterior credible interval overlaps zero quite heavily. Among females, reproductive skew is approximately constant across populations, but the posterior estimate of M is most precise in the Kipsigis where population size is largest. Frame (b): posterior estimates of M for various simulated datasets, with various levels of skew and mean RS. Reproductive success was drawn randomly from a Negative Binomial distribution with a mean rate per exposure time unit of 1.0=low, 7.0=mid, and 20.0=high. To alter skew, we set the exponent of a rate scaling random effect to 0.01=low skew, 0.31=mid skew, and 0.61=high skew (as shown in figure 1a). Within each frame, we see the posterior distributions of M for various levels of sample size. Posterior estimates of M map closely onto the point estimates of M, plotted as blue bars. In general, we see that as the sample size increases, the posterior distributions narrow, reflecting more precise estimates of M. When the RS rate is low, there is necessarily less RS data and thus greater uncertainty in M, which is reflected in wider posterior credible regions. (Online version in colour.)