Abstract

Silk fibroin (SF) hydrogels find wide applications in tissue engineering. However, their scope has been limited due to the long gelation time in ambient conditions. This paper shows the reduction in gelation time of silk fibroin to minutes upon doping with a newly synthesized lauric acid sophorolipid (LASL). LASL comprises a fatty acid, lauric acid (with a 12-carbon aliphatic chain), that is derivatized by glucose molecules using a non-pathogenic yeast Candida bombicola. LASL was characterized using spectroscopic (Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy) and chromatographic (high-performance liquid chromatography, thin-layer chromatography, and high-resolution mass spectrometry) methods. This gelation of SF is comparable to the effect of an anionic surfactant, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). The microstructure of SF-LASL hydrogels was investigated by small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) measurements and exhibited the beads-on-a-necklace model. The rheological properties of these hydrogels show similarity to SF-SDS hydrogels, therefore presenting a greener alternative for tissue engineering applications.

Introduction

Silk fibroin (SF) is a natural protein polymer extracted from the cocoons of Bombyx mori silkworm. It has excellent biocompatibility, enhanced thermo-mechanical stability, low immunogenicity, and also controlled biodegradation.1 These properties make it suitable for use in biomedical applications. Silk fibroin hydrogels are increasingly being explored for applications ranging from tissue regeneration to organ repair.2,3 In an aqueous solution, SF predominantly exhibits random coil secondary structure, and a change in its conformation to beta sheet structure causes its transition from sol to gel.4 This sol to gel transition requires days to complete and can be accelerated by addition of a gelling agent. A previous study by Kaplan et al. showed that interaction of SF with SDS can reduce the gelation time for SF to ∼20 min.5 The hydrogels so-obtained have a sufficiently high bulk modulus and exhibit mechanical stability, suggesting that these hydrogels could be used for biomedical applications. Further, it has also been shown that SDS interacts with hydrophilic segments of SF through its hydrophilic head and hence triggers gelation.6

Previous studies also showed that biosurfactants such as sophorolipids can be used to induce gelation of SF.7 Sophorolipids (SL) are amphiphilic molecules with a hydrophobic lipid tail and a hydrophilic carbohydrate, i.e., a sophorose head. They are produced by certain selective non-pathogenic yeasts mainly by Candida bombicola. When the yeast cells are fed with a glucose and lipid substrate, i.e., fatty acids, the cells derivatize the fatty acid chain with 2 glucose units. The formed product is synthesized as an open chain, i.e., acidic, and closed chain, i.e., lactonic.8 The lactonic SL is more hydrophobic and has biocidal properties, whereas the acidic form has better solubility in water.9 Different SLs can be synthesized by changing the lipid substrate, i.e., fatty acids with varying carbon chain length. Hence, these different SLs exhibit antibacterial, anticancer, antifungal, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory activity.10−14 However, they accelerate the gelation only to a limited extent, and the gelation time here was typically found to be of the order of approximately few hours.7

In this study, we have synthesized a biosurfactant—lauric acid sophorolipid (LASL). Similar to SDS, lauric acid (LA) has a hydrophobic 12-carbon long aliphatic chain, and the synthesis of short-chain fatty acid-based sophorolipids has been found to be challenging.15 This is the first report of a successful synthesis of a sophorolipid incorporating lauric acid as the fatty acid chain using a non-pathogenic yeast Candida bombicola. We have extensively characterized the product obtained using complementary spectroscopic and chromatographic techniques. Unlike SDS, LASL is a green molecule, and sophorolipids have been shown to have excellent biological properties such as antimicrobial, antiviral, and anticancer. Further, just like SDS, it is interesting to see that LASL also accelerates the gelation of SF, and the gelation time is also similar for both the surfactants. Thus, this paper describes the synthesis and characterization of LASL and its effect on gelation time of silk fibroin hydrogels. Eventually, the silk fibroin-LASL hydrogel is characterized for rheological properties and microstructure analysis by SANS experiments.

Results and Discussion

LASL production using C. bombicola cells adapted to LA was successfully carried out by the resting cell method. The yield of LASL obtained by the production method utilizing 2 g % cell and 1 g % LA was 5.67 g/L. The purified product was a crystalline solid, brown in color, and had a sweet odor. Primary characterization of the product such as oil displacement assay and thin-layer chromatography (TLC) to test its surface-active property was carried out. The results are shown in the Supporting Information (Figures S1 and S2). Formation of the zone of clearance in the oil layer due to addition of LASL solution confirmed its surfactant activity. The developed TLC plate also confirmed conversion of LA into the LASL product, which is found to be a mixture of different structures. The surface activity of LASL was also characterized by determination of critical micellar concentration (CMC) by taking surface tension measurements at different LASL concentrations in water. The surface tension of water was reduced from 71 to 34.7 mN/m on addition of LASL. The CMC of LASL was found to be 40 mg/L (Figure S3).

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

The chromatogram in Figure 1A shows that the hydrophobic LA has been derivatized into the acidic and lactonic form of SL. The proportion of the acidic SL form is higher than that of lactonic and is eluted between ∼3.5 and 5 min represented by two sharp peaks. Further small peaks at ∼10, 12, and 16 min indicate the presence of lactonic SL.

Figure 1.

(A) HPLC chromatogram of the product (LASL) using the solvent system ACN and water (80:20). (B) FTIR spectra of LA, glucose, and LASL.

FTIR

The FTIR spectrum of the precursor molecules LA and glucose along with LASL was measured to check incorporation of sophorose moieties onto the LA molecule confirming formation of LASL. (Figure 1B). The primary precursor LA spectrum shows the peak at 1695 cm–1 depicting the carbonyl stretch of the −COOH group. The peaks at 2914 and 2849 cm–1 and different peaks between 1400 and 1500 cm–1 (1470, 1449, and 1412 cm–1) represent characteristic −CH2 groups (aliphatic C12 chain). Stretching vibrations of different −OH groups present in the glucose molecule are observed as a broad peak at 3260 cm–1. Other peaks at 1026 and 985 cm–1 are also seen, which show the presence of C–O stretching as well as a peak at 2944 for −CH groups. In the case of LASL, stretching vibrations of −CH2 groups at 2914 and 2850 cm–1 and that of carbonyl group at 1699 cm–1 are observed, which confirms the presence of LA moieties in LASL. Further, peaks at 1085 and 933 cm–1 representing C–O stretch in the sugar and a broad peak at 3440 cm–1 of −OH group stretching vibrations confirm the presence of glucose moieties in LASL. Finally, a peak at 1244 cm–1 corresponds to a C (−O)–O–C ester bond between the acetyl group and 6′/6″ carbon of glucose. FTIR has been used as a first preliminary test to confirm the formation of sophorolipids.16

HRMS

In the HRMS run, various molecules from the mixture of molecules get separated according to their molecular weight and thus have distinct retention time, which reflects in a chromatogram. Thus, different molecules from the LASL product were identified by analyzing the chromatogram based on their molecular weight.

The biosynthesis of SL involves three steps

-

(1)

Hydroxylation of ω (terminal) or ω-1 (subterminal) carbon on fatty acid. This process is catalyzed by cytochrome P450 monooxygenase belonging to microsomal class II monooxygenase. The hydroxyl group provides attachment for glucose molecules through an ether bond.

-

(2)

Glycosylation of an ω or ω-1 hydroxyl group. A glycosyltransferase I enzyme carries out the coupling of the first glucose (position C1′) molecule using UDP-glucose. The second glucose molecule is transferred onto the first glucose molecule (position C2′) by glycosyltransferase II.

-

(3)Modification of native sophorolipid

- Lactonization. This process happens by an esterification reaction between hydroxyl groups on C4″ from glucose and the carboxyl group of fatty acid.

Thus, different types of SL structures can be found in the final LASL product, i.e., native acidic SL, lactonic SL, and mono-/di-acetylated acidic/lactonic SL. Table 1 contains the structures of LASL, which were found in HRMS analysis and were drawn using ChemDraw software. Both acidic and lactonic forms of LASL as well as their mono-/di-acetylated forms were identified. The attachment of the sophorose moiety can occur from the COOH end of the fatty acid as well as at the penultimate CH group in the hydrophobic tail. Sophorose modification at both ends could be found in the HRMS data analysis.

Table 1. Structures of LASL Identified in the LC-HRMS Analysis.

Rheology Studies for Hydrogels

The LASL product so-obtained and characterized was further evaluated for its ability to induce gelation of RSF solutions. Unlike LA, the LASL product was soluble in water up to a concentration of 1.5% w/v at pH 8. The derivatization of the LA molecule with a hydrophilic sophorose head enables its dissolution in water. The obtained solutions were turbid and were found to be stable at 37 °C for more than 24 h.

Rheology experiments were performed to determine gelation time (GT) of RSF (3% w/v) in the presence of LASL solutions (0.5, 1, and 1.5% w/v). These experiments also gave an insight into the strength of the hydrogels formed. The gelation was performed at 37 °C, i.e., physiological temperature considering their potential use in biomedical application. As seen in Figure 2A, the storage modulus (G′) of all SF-LASL solutions initially was insignificant, and the loss modulus (G″) was measured to be ∼0.4 Pa. The values of both G′ and G″ increased gradually with time to finally reach a plateau. GT was calculated as the time point where G′ and G″ cross over.17 The GT of 3% w/v RSF when mixed with 1.5, 1, and 0.5% w/v LASL solution was determined to be ∼18, 22, and 133 min respectively. The G′ of all the hydrogels was observed to be 1 kPa and did not change with increasing the concentration of LASL. Thus, it can be inferred that as the concentration of LASL increased from 0.5 to 1.5% w/v, the corresponding decrease in the GT for SF was observed.

Figure 2.

(A) Plot of time versus G′/G″ (Pa) from time sweep experiment using 3% w/v RSF solution in the presence of different concentrations of LASL. (B) Plot of time (min) versus OD at 550 nm for hydrogels using 3% w/v RSF in the presence of different concentrations of LASL.

The gelation of the mixture of RSF with LASL was also monitored by measuring the OD at 550 nm at a definite interval of time. In this case, GT was calculated as the time point at which the OD 550 nm was half of its maximum value.5 The GT values for 1.5, 1, and 0.5% w/v were determined to be ∼31, 40, and 195 min. Hence, reduction in GT with increase in LASL concentration can be observed in Figure 2B, which corroborates with results obtained from rheology experiments.

To check the effect of increasing concentration of RSF (to 5 and 10% w/v) on GT with concentration of LASL solution constant as 1.5% w/v, rheology experiments as well as measurements of OD at 550 nm were performed. Figure 3A depicts the results of the time sweep experiment where reduced GT for 10 and 5% w/v is observed to be ∼5 and ∼9 min. Similar reduction in GT of RSF is observed when OD of the solution mixture was monitored at 550 nm (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) Plot of time (min) versus G′/G″ (Pa) from time sweep experiment using 1.5% w/v LASL in the presence of different concentrations of RSF. (B) Plot of time (min) versus OD at 550 nm for hydrogels using 1.5% w/v LASL in the presence of different concentrations of RSF.

It can also be observed that with increasing concentration of SF, the storage modulus drastically increases by multiple orders of magnitude. At the highest concentration, i.e., 10% w/v SF, the G′ is seen to be 100 kPa. In a study by Li et al., gelation behavior of SF was monitored in the presence of anionic surfactants SDS, SDBS, a non-ionic surfactant Triton, and cationic surfactants OTAB, DDBAB, and CPC. The study showed that only ionic and non-ionic surfactants (SDBS and Triton) exhibit similar effects on SF as compared to SDS but have longer GT, and the strength of the hydrogel is also comparatively lower. High-strength robust RSF-SDS gels were formed in this study.18 In our previous study, SF-SDS hydrogels with moduli of ∼1 kPa similar to that of SF-LASL were observed.6 Thus, it can be concluded that our synthesized biosurfactant LASL is equally efficient in reducing the GT as well as forming high-strength hydrogels. Also, the SF-LASL hydrogels have moduli high enough to be explored for their application in tissue engineering.

In the sol to gel transition of SF, the secondary random coil conformation of SF in aqueous solution changes to beta sheets.19 The FTIR data in various reports show an increase in the percent beta sheet content of the system on gelation by addition of SDS and another biosurfactant oleic acid sophorolipid.6,17

As mentioned earlier, GT of SF-LASL hydrogels is inversely proportional to the concentration of LASL in the hydrogel. However, an exactly reverse trend is observed in the case of SDS. In an earlier study, it was seen that as SDS concentration increases in the hydrogel, the GT of the SF-SDS hydrogel increases.6 The contrasting effect of these two similar molecules was intriguing and hence led us to explore the microstructures formed in SF-LASL hydrogels by using SANS. The SANS results could help in understanding the difference between the interaction of these molecules with the SF chain.

SANS Study

The SANS profiles for the hydrogels formed when RSF is mixed with LASL of three different concentrations are shown in Figure 4. The structure of protein-surfactant complexes depends on the interplay of electrostatic as well as hydrophobic interactions between these molecules when mixed. Ionic surfactants, even at low concentrations, are known to denature/alter protein conformations.6,20,21 In the present system of RSF-LASL, too, a change in the conformation of RSF proteins can be expected. The secondary structure of RSF when mixed with LASL has been characterized by the random flight model. This model describes a beads-on-a-necklace-like complex.22 The unfolded protein binds the surfactant micelles in the protein-surfactant cluster, forming small micelle-like clusters along the chain of the protein leading to a bead-necklace kind of morphology (fibrils). The close approach of hydrophobic regions of SL and RSF eventually results in the formation of gel networks. The model employed for analyzing SANS data has been described in terms of the micellar core radius (Rc), the number of micelles attached per cluster (NCLU), and the separation between the center of two nearest micelles (D) in the cluster. These parameters are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 4.

SANS data and model fits for hydrogels synthesized using 3% w/v RSF with varying concentrations of LASL (black lines denote model fits to the SANS data).

Table 2. Fitted Parameters from the Analyzed SANS Data of RSF-LASL Systems.

| system | micellar core radius, Rc (Å) | number of micelles per cluster, NCLU | separation between the center of two nearest micelles, D (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3% w/v RSF + 0.5% w/v LASL | 16.1 | 29 | 39.8 |

| 3% w/v RSF + 1.0% w/v LASL | 14.8 | 49 | 36.9 |

| 3% w/v RSF + 1.5% w/v LASL | 14.1 | 52a | 36.2 |

Apart from this, there are free micelles in the solution.

With increasing concentration of LASL, micellar sizes have been found to decrease, whereas the number of micelles per cluster increases, thereby enhancing the propensity of fibril formation and subsequent gelation. This is in agreement with the observation of faster gelation time at higher LASL concentration in rheological experiments. It may be noted that RSF with 1.5% w/v LASL has free LASL micelles present in the system. This observation is quite opposite to what has been witnessed for anionic surfactant SDS.6 With increasing concentration of SDS, micellar size increases, and the number of micelles per cluster decreases, thereby reducing the propensity of fibril formation. This is in agreement with the observation of longer gelation time at higher SDS concentration in rheological experiments. It may be noted that RSF with 1.5% w/v SDS also has free SDS micelles. On the other hand, the interaction of RSF with oleic acid-based sophorolipids (as indicated by MSL, 3% w/v) has also been probed earlier and demonstrates some interesting features. It has been observed that the presence of lactonic SL (LSL) in the MSL (along with acidic SL in a 3:1 ratio) solution allows some molecules of hydrophobic LSL to interact with the hydrophobic domains (glycine- and alanine-rich patches) of RSF, resulting in the unfolding of RSF. Due to the presence of non-interacting ASL in MSL, the formation of partial beads-on-a-necklace-like complexes and faster gelation were confirmed in the study.17 This indicates that the interaction and the resultant structure in the case of oleic acid-based SL and LASL interacting with RSF have high similarity, which results in a similar gelation behavior.

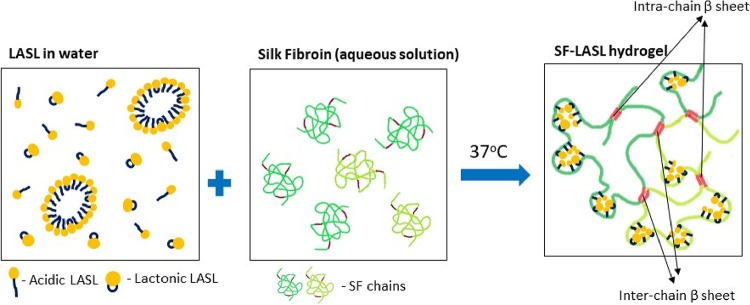

SDS is a synthetic surfactant and can thus be obtained with extremely high purity. Meanwhile, LASL is a mixture of ASL and LSL and their acetylated forms (determined by various techniques such as TLC, HPLC, and HRMS), which also concludes that the interaction of these two surfactants with the SF chain is distinctly different (Figure 5). Further, the HPLC graph shows that the ratio of ASL/LSL is high. As mentioned earlier, the lactonic form of LASL interacts with the hydrophobic domains on the SF chain and facilitates unfolding of the SF chain. This unfolding increases the intra- and interchain interactions between the hydrophobic domains. With concentration of LASL solutions increasing from 0.5 to 1.5% w/v, the concentration of the lactonic form increases and in turn accelerates the unfolding of the chain. Hence, GT of SF being inversely proportional to concentration of LASL solutions can be justified. These results are in agreement with those observed when an oleic acid sophorolipid was used as a gelling agent.

Figure 5.

Schematic representing the interaction between SF chains and LASL molecules in the hydrogels.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Microorganisms

Silk fibers of Bombyx mori silkworm used in this work were procured from Central Sericultural Research and Training Institute, Mysuru, India. Chemicals required in silk processing, i.e., NaHCO3 and lithium bromide, were procured from Merck and Sigma Aldrich, respectively. Different media components used for yeast culture and fermentation, namely, malt extract, glucose, yeast extract, and mycological peptone as well as nutrient agar powder were obtained from Himedia, India. Minor media components (salts) MgSO4, Na2HPO4, NaH2PO4, and (NH4)2SO4 were purchased from SRL, India. Lauric acid (LA), used as a precursor for LASL production, was procured from Loba Chemicals.

The sophorolipid product (LASL) was synthesized using a non-pathogenic yeast Candida bombicola (ATCC 22214) maintained on MGYP medium slants (malt extract, 0.3 g %; glucose, 10 g %; yeast extract, 0.3 g %; mycological peptone, 0.5 g %) for growth at 28 °C and stored at 4 °C.

Preparation of Regenerated Silk Fibroin (RSF)

Regenerated silk fibroin or RSF was prepared from the silk fibers of Bombyx mori silkworm, according to the protocol described earlier.7 Initially, the fibers were treated by boiling the fibers in 0.05% w/v NaHCO3 twice for an interval of half an hour. This is called degumming, which removes the sericin protein from the SF fibers. The fibers were then allowed to dry in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 48 h. To prepare the aqueous solution of SF, the degummed fibers were dissolved in lithium bromide salt solution (Sigma Aldrich) of 9.3 M for 4 h at 60 °C. The LiBr salt was dialyzed against DI water for 48 h to remove the salt completely. The dialyzed RSF solution was later centrifuged to remove impurities. The concentration of silk fibroin was determined gravimetrically to be approximately 5% w/v. Further experiments were carried out by diluting the RSF solution to 3% w/v using deionized water. This solution was lyophilized and stored for further experiments. Lyophilized RSF was used in the SANS measurements.

Production of the Lauric Acid-Derived Sophorolipid

The sophorolipid product was synthesized using a non-pathogenic yeast Candida bombicola (ATCC 22214) by the resting cell method. Briefly, C. bombicola cells were initially grown in 10 mL of an MGYP medium for 24 h. Then, the cells were transferred to 90 mL of the culture medium or CM (glucose, 10 g %; yeast extract, 0.1 g %; (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 g %; Na2HPO4, 0.2 g %; NaH2PO4, 0.7 g %; MgSO4, 0.03 g %). To adapt the cells to lauric acid, 200 mg of LA powder was added to this CM and was incubated at 28 °C for 48 h. This step was repeated 2–3 times. A starter culture was then set up by inoculating the adapted cells in CM. After 48 h, the C. bombicola cells from the starter culture were collected and used for LASL production in 100 mL of CM (set up in a 1 L Erlenmeyer flask). Production of LASL was carried out for a duration of 7 days at 28 °C. The cell loading and LA concentration were optimized to be 2 and 1 g %, respectively.

Extraction of the LASL Product

LASL was produced extracellularly by the yeast cells, which was purified by a solvent extraction method. Cells in the production media were removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was mixed with equal volume of ethyl acetate. An ethyl acetate fraction was collected as the LASL in the production media is extracted into the organic phase and anhydrous sodium sulfate was added to it to ensure complete water removal. Ethyl acetate was removed using a rota-evaporating method, and finally, LASL was air-dried to remove all traces of the solvent.

Characterization of the LASL Product

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

HPLC was performed for preliminary confirmation of LASL formation. LASL samples prepared in 100% ACN were run in a Hitachi HPLC system through a Symmetry C18 column (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm) and were detected at 215 nm using a UV/Visible detector. Total run time for the samples was 30 min. The solvent system used for the run was ACN/water (80:20).

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

LASL, LA, and glucose were characterized using FTIR to confirm incorporation of glucose molecules onto LA molecules and formation of LASL. All the measurements were carried out on a Bruker Tensor II FTIR system using Platinum ATR mode. Spectra were recorded by measuring 40 scans in the range of 500–4000 cm–1 for all the samples and 32 scans for the background.

High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS)

To identify the structure of compounds formed in the LASL product, HRMS was performed on a Thermo Scientific, Hybrid Quadrupole Q Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer. The LASL sample was prepared in acetonitrile. A total run of 10 min was carried out by gradient solvent elution from 5% ACN in water to 100% ACN with a flow rate of 500 μL/min. A liquid chromatography pump (Accela 1250) was used, and the samples were passed through a Thermo Scientific Hypersil ODS C18 column, 100 mm length with 3 μm particle size. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive electrospray ionization mode, where the spray voltage was at 3600 V, the capillary temperature at 320 °C, the S-lens RF level at 50, automatic gain control (AGC) at 1×106, and maximum injection time of 120 ms. Nitrogen was used as the sheath gas, spare gas, and auxiliary gas, set at 35, 2, and 8 (arbitrary units), respectively. A volume of 2 μL of the sample was injected, and scans were performed using positive polarity in the mass range 100–1500 m/z. Data was analyzed with Thermo Scientific Xcalibur software. The mass spectrum was scanned for different predicted structures of LASL and their hydrogen, sodium, and ammonium adducts.

Hydrogel Preparation and Rheology Studies

Preparation of SF hydrogels involved mixing equal volumes of RSF and the LASL solution. LASL was used at three different concentrations (0.5, 1, 1.5% w/v). RSF was also used at three different concentrations (3, 5, 10% w/v). RSF solutions were used at their native pH, whereas pH of all the LASL solutions was adjusted to 8 using 0.1 M NaOH solution. An Anton Paar MCR301 rheometer was used to determine gelation and mechanical properties of the hydrogels. A time sweep experiment was performed using cup and bob geometry (CC-17) at 0.5% strain using a frequency of 6.28 rad s–1 at 37 °C.

Optical Density Measurements

SF-LASL hydrogels were prepared as described earlier. The mixture (1 mL) of 3% w/v RSF solution and LASL solution at a 1:1 ratio was transferred in a 24 well plate (Axygen, India). The sol to gel transition was monitored by measuring the OD of the solution at 550 nm at definite time intervals.

Small-Angle Neutron Scattering (SANS) Measurements

Small-angle neutron scattering experiments were performed at the SANS diffractometer at the Guide Tube Laboratory, Dhruva Reactor, Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, Mumbai, India.23 In SANS, one measures the coherent differential scattering cross section (dΣ/dΩ) per unit volume as a function of wave vector transfer Q (= 4π sin θ/λ, where λ is the wavelength of the incident neutrons and 2θ is the scattering angle). The mean wavelength of the monochromatized beam from a neutron velocity selector is 5.2 Å with a spread of Δλ/λ ∼ 15%. The angular distribution of neutrons scattered by the sample is recorded using a 1 m-long one-dimensional He3 position-sensitive detector. The instrument covers a Q-range of 0.015–0.25 Å–1. LASL solutions (concentrations of 0.5, 1, and 1.5% w/v) and RSF solution (3% w/v) were mixed in equal volumes and monitored in SANS experiments post gelation. The data analysis was done after the data were corrected for the direct beam and background contributions. The data from the microstructures formed inside the hydrogels have been analyzed by comparing the scattering from different models to the experimental data as described in the Supporting Information.

Conclusion

The biosurfactant, lauric acid-derived sophorolipid, was synthesized by using Candida bombicola, and structures present in the final product were determined by HRMS experiment. Acidic and lactonic LASL along with their mono- and di-acetylated forms were found in the extracted LASL product. The interactions between LASL and SF were studied using rheology and SANS measurements. The results of the study show that LASL is equally effective in reducing the GT of SF as SDS, an anionic surfactant. By increasing the concentration of LASL, corresponding reduction in GT of SF is observed. The strength of the hydrogels is determined to be 1 k Pa at 3% w/v concentration of SF and further increases up to 100 kPa by increasing the concentration of SF to 10% w/v, which also reduces the GT even further. The measurements from the SANS experiment show that similar to OASL, the lactonic form interacts with the hydrophobic portion on the SF chain, and ASL molecules form micelles on the SF chain and give rise to beads on a string structure. In contrast to SDS, LASL is a green molecule. It is biodegradable and biocompatible and has bioactive properties. Thus, the formed hydrogels have a promising future in tissue engineering.

Acknowledgments

A.N. acknowledges the support of Department of Science and Technology under the SERB Extra Mural Research Grant (FILE NO.EMRJ2017/001899) for financially supporting this work.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c03411.

Figures from oil displacement experiment, TLC chromatogram, CMC graph, picture of an SF-LASL hydrogel, plots from HRMS experiment, and SANS analysis (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Vepari C.; Kaplan D. L. Silk as a Biomaterial. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2009, 32, 991–1007. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman G. H.; Diaz F.; Jakuba C.; Calabro T.; Horan R. L.; Chen J.; Lu H.; Richmond J.; Kaplan D. L. Silk-Based Biomaterials. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 401–416. 10.1016/S0142-9612(02)00353-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Mooney D. J. Designing Hydrogels for Controlled Drug Delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16071. 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto A.; Chen J.; Collette A. L.; Kim U. J.; Altman G. H.; Cebe P.; Kaplan D. L. Mechanisms of Silk Fibroin Sol-Gel Transitions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 21630–21638. 10.1021/jp056350v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.; Hou J.; Li M.; Wang J.; Kaplan D. L.; Lu S. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Induced Rapid Gelation of Silk Fibroin. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 2185–2192. 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirlekar S.; Ray D.; Aswal V. K.; Prabhune A.; Nisal A.; Ravindranathan S. Silk Fibroin-Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Gelation: Molecular, Structural, and Rheological Insights. Langmuir 2019, 14870–14878. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b02402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey P.; Nawale L.; Sarkar D.; Nisal A.; Prabhune A. Sophorolipid Assisted Tunable and Rapid Gelation of Silk Fibroin to Form Porous Biomedical Scaffolds. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 33955–33962. 10.1039/C5RA04317D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bogaert I. N. A.; Zhang J.; Soetaert W. Microbial Synthesis of Sophorolipids. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 821–833. 10.1016/j.procbio.2011.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira M. R.; Camilios-Neto D.; Baldo C.; Magri A.; Colabone Celligoi M. A. P. Biosynthesis And Production Of Sophorolipids. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2014, 3, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Nawale L.; Dubey P.; Chaudhari B.; Sarkar D.; Prabhune A. Anti-Proliferative Effect of Novel Primary Cetyl Alcohol Derived Sophorolipids against Human Cervical Cancer Cells HeLa. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0174241 10.1371/journal.pone.0174241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsanyiova M.; Patil A.; Mukherji R.; Prabhune A.; Bopegamage S. Biological Activity of Sophorolipids and Their Possible Use as Antiviral Agents. Folia Microbiol. 2016, 61, 85–89. 10.1007/s12223-015-0413-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross R. A.; Shah V.. Method for Neutralizing Fungi Using Sophorolipid and Antifungal Sophorolipids for Use Theren. United States Pat.US8796228B22014, 2, 0–10.

- Dengle Pulate V.; Bhagwat S.; Prabhune A. Antimicrobial and SEM Studies of Sophorolipids Synthesized Using Lauryl Alcohol. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2013, 16, 543–181. 10.1007/s11743-012-1378-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin R.; Pierre J.; Schulze R.; Mueller C. M.; Fu S. L.; Wallner S. R.; Stanek A.; Shah V.; Gross R. A.; Weedon J.; Nowakowski M.; Zenilman M. E.; Bluth M. H. Sophorolipids Improve Sepsis Survival: Effects of Dosing and Derivatives. J. Surg. Res. 2007, 142, 314–319. 10.1016/j.jss.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bogaert I.; Fleurackers S.; Van Kerrebroeck S.; Develter D.; Soetaert W. Production of New-to-Nature Sophorolipids by Cultivating the Yeast Candida Bombicola on Unconventional Hydrophobic Substrates. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2011, 108, 734–741. 10.1002/bit.23004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daverey A.; Pakshirajan K. Production, Characterization, and Properties of Sophorolipids from the Yeast Candida Bombicola Using a Low-Cost Fermentative Medium. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2009, 158, 663–674. 10.1007/s12010-008-8449-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey P.; Kumar S.; Aswal V. K.; Ravindranathan S.; Rajamohanan P. R.; Prabhune A.; Nisal A. Silk Fibroin-Sophorolipid Gelation: Deciphering the Underlying Mechanism. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 3318–3327. 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b01069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Zheng Z.; Yang Y.; Fang G.; Yao J.; Shao Z.; Chen X. Robust Protein Hydrogels from Silkworm Silk. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 1500–1506. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b01463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koh L. D.; Cheng Y.; Teng C. P.; Khin Y. W.; Loh X. J.; Tee S. Y.; Low M.; Ye E.; Yu H. D.; Zhang Y. W.; Han M. Y. Structures, Mechanical Properties and Applications of Silk Fibroin Materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2015, 46, 86–110. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2015.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chodankar S.; Aswal V. K.; Kohlbrecher J.; Vavrin R.; Wagh A. G. Surfactant-Induced Protein Unfolding as Studied by Small-Angle Neutron Scattering and Dynamic Light Scattering. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2007, 19, 326102. 10.1088/0953-8984/19/32/326102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehan S.; Aswal V. K.; Kohlbrecher J. Tuning of Protein-Surfactant Interaction to Modify the Resultant Structure. Phys. Rev. E 2015, 92, 032713. 10.1103/PhysRevE.92.032713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giehm L.; Oliveira C. L. P.; Christiansen G.; Pedersen J. S.; Otzen D. E. SDS-Induced Fibrillation of α-Synuclein: An Alternative Fibrillation Pathway. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 401, 115–133. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aswal V. K.; Goyal P. S. Small-Angle Neutron Scattering Diffractometer at Dhruva Reactor. Curr. Sci. 2000, 79, 947–953. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.