Abstract

Schizophrenia (SZ) is a psychiatric disorder with a convoluted etiology that includes cognitive symptoms, which arise from among others a dysfunctional dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC). In our search for the molecular underpinnings of the cognitive deficits in SZ, we here performed RNA sequencing of gray matter from the dlPFC of SZ patients and controls. We found that the differentially expressed RNAs were enriched for mRNAs involved in the Liver X Receptor/Retinoid X Receptor (LXR/RXR) lipid metabolism pathway. Components of the LXR/RXR pathway were upregulated in gray matter but not in white matter of SZ dlPFC. Intriguingly, an analysis for shared genetic etiology, using two SZ genome-wide association studies (GWASs) and GWAS data for 514 metabolites, revealed genetic overlap between SZ and acylcarnitines, VLDL lipids, and fatty acid metabolites, which are all linked to the LXR/RXR signaling pathway. Furthermore, analysis of structural T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in combination with cognitive behavioral data showed that the lipid content of dlPFC gray matter is lower in SZ patients than in controls and correlates with a tendency towards reduced accuracy in the dlPFC-dependent task-switching test. We conclude that aberrations in LXR/RXR-regulated lipid metabolism lead to a decreased lipid content in SZ dlPFC that correlates with reduced cognitive performance.

Subject terms: Molecular neuroscience, Schizophrenia

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SZ) is a psychiatric disorder with a convoluted etiology and a lifetime prevalence of 0.84%. It is thought that an interplay between genetic, epigenetic, and environmental risk factors is involved in SZ etiology1. Symptoms of SZ include positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms2. The positive symptoms comprise delusions and hallucinations3, the negative symptoms are a loss of typical affective functions2, and the most prominent cognitive symptoms of SZ are deficits in attention4 and executive functioning5–7. There are currently no effective pharmacological treatment strategies that target the negative and cognitive symptoms of SZ8. Cognitive symptoms and related changes in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of SZ patients are already present before disease onset9 and contribute negatively to functional outcome10–13. Cognitive deficits are found in individuals at high risk to develop SZ14 and family members of SZ patients15, albeit to a lower degree. The various subregions of the PFC are involved in deficits in specific cognitive domains16. For example, although ventro-lateral PFC functioning remains largely unaffected, impaired dorsolateral (dl)PFC-dependent processes are thought to underlie a range of cognitive deficits in SZ17–19. In addition, dlPFC activation during the performance of cognitive tasks is decreased in SZ patients18,20,21.

Transcriptomic studies on the PFC of SZ patients have increased our understanding of the molecular mechanisms contributing to the PFC-dependent cognitive impairment in SZ. The majority of transcriptomic studies performed on SZ dlPFC (RNA sequencing22–29 or microarray30–32 analyses) have been conducted on a mix of gray and white matter. However, gray and white matter display discrete gene expression patterns33, and therefore investigating the transcriptome of a gray and white-matter mix does not allow the detection of gene expression differences that arise from and are specific to either gray or white matter. One transcriptomic study has been performed on SZ PFC gray matter, but did not specify the PFC subregion that was used34. Yet, spatial differences in gene expression patterns exist throughout the cortex35 and PFC subregions have distinct contributions to the cognitive deficits in SZ16. Only two transcriptomic studies published to date have analyzed solely the gray matter of the SZ dlPFC subregion, with one study reporting differences in the axon guidance pathway36 and the other analyzing the expression of only the delta 4-desaturase, sphingolipid 2 (DEGS2) gene37.

In the current study, we sequenced the transcriptome of the gray matter of dlPFC in SZ and controls. As we found that the differentially expressed genes were enriched in Liver X Receptor/Retinoid X Receptor (LXR/RXR)-mediated lipid metabolism genes, we next investigated whether SZ has a genetic link with lipid metabolism. We indeed identified shared genetic etiology between SZ and among other acylcarnitines, very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) lipids, and fatty acid metabolites. Finally, exploratory analyses of structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data were in accordance with a lower lipid content of the dlPFC gray matter in SZ patients as compared to controls and correlated with reduced cognitive performance. Thus, distortions in lipid homeostasis play a key role in the cognitive symptoms of SZ.

Materials and methods

Samples and RNA sequencing

Human post-mortem dlPFC brain tissue from four chronic SZ patients and four control individuals was obtained from the Dutch Brain Bank (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Sample size was based on tissue availability. Sections of 300 µm were obtained in a cryostat (Leica) at −15 °C and two to three punches were collected from different places in the gray matter and in the white matter using a 2.00 mm punch needle (Harris). Punches were frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 °C until RNA isolation using RNeasy lipid tissue mini kit (74804 Qiagen). Isolated RNA was sent for quality control, RNA sequencing, and bioinformatics data analysis to BGI Genomics. Agilent 2100 Bio Analyzer was used to determine RNA quality and RNA integrity numbers of all RNA samples were 6.7 or higher. RNA sequencing was performed using BGISEQ-500 platform generating 6.71 Gb bases per sample. Using hierarchical indexing for spliced alignment of transcripts or HISAT, clean reads were mapped to the reference genome UCSC HG38 with an average of 92.06% mapped reads. Gene expression levels (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) were calculated using RSEM and NOIseq algorithms were then used to determine genes differentially expressed in SZ patients and controls. Significantly differentially expressed genes (probability > 0.8) were used for analysis with the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software package (Qiagen). RNA sequencing and RNA-sequencing data analysis were performed by researchers that were blinded for disease state. RNA-sequencing data are freely available through https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12640460.v1

Quantitative real-time PCR

For quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis, per sample 350 μg RNA was treated with DNase I (Fermentas) and cDNA was synthesized using the Revert Aid H-minus first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific). cDNA was subsequently diluted 1 : 20 in MilliQ H2O and stored at −20 °C until qPCR analysis. qPCR samples contained 2.0 μL diluted cDNA, 0.8 μL 5 μM forward primer, 0.8 μL 5 μM reverse primer, 5 μL SybrGreen mix (Roche), and 1.8 μL MilliQ H2O. qPCR was performed with a Rotor Gene 6000 Series (Corbett Life Sciences) using a three-step paradigm with a fixed gain of 8. Fifty cycling steps of 95, 60, and 72 °C were applied and fluorescence was acquired after each cycling step. Primers were designed with NCBI Primer-Blast and synthesized by Sigma (for primer pair sequences, see Supplementary Table S1). Melting temperature was used to check whether a single PCR product was generated and the take off and amplification values of the housekeeping genes (Ppia and Gapdh) were used to determine the normalization factor with GeNorm38 after which normalized mRNA expression levels were calculated. qPCR data were analyzed using Levene’s test for equality of variances and two-tailed independent samples T-tests in SPSS Statistics 21. Individual data points and means were plotted using Graphpad Prism 4. Researchers were blinded for disease state during qPCR analysis.

Shared genetic etiology

Two SZ genome-wide association studies (GWASs) and four metabolite GWAS datasets were used to calculate shared genetic etiology between SZ and metabolite levels. We first calculated shared genetic etiology between 561 metabolites and SZ using previously published SZ GWAS data that was obtained from 33,426 SZ patients from European ancestry39. We then replicated the calculation using a second SZ GWAS dataset, namely the GWAS data from 36,989 SZ patients as provided by the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium40, which includes the same patients from European descent, but also includes individuals with East-Asian ancestry. The metabolite GWAS data were obtained from Rhee et al.41 including 268 metabolite GWASs, Draisma et al.42 including 129 metabolite GWASs, Kettunen et al.43 including 123 metabolite GWASs, and Ahola-Olli et al.44 including 41 cytokine GWASs, and included 2076, 7478, and 24,925 participants of European decent, and 2019 Finnish participants, respectively. Shared genetic etiology was calculated using the freely available program PRSice version 1.2345 with PLINK version 1.9 and based on the method of Johnson et al.46. Metabolite GWAS data were taken as base samples and SZ GWAS data as the target sample, and correlation results were weighted by the SZ group size. Using PRSice, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were clumped to remove linkage disequilibrium (LD) with an LD threshold of 0.1, a distance threshold of 250 kb, and the 1000 Genomes Project data as genotype reference47. A range of SNP significance thresholds was used (pT < 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5) to calculate shared genetic etiology and the p-values obtained using these thresholds were corrected with Bonferroni multiple comparisons correction for the number of metabolites tested.

Analysis of the dlPFC gray-matter MP-RAGE signal and correlation with task-switching accuracy

The Consortium for Neuropsychiatric Phenomics made available an MRI dataset including 125 healthy individuals (median age = 28 years old, 53% female) and 50 individuals (median age = 37.5 years old, 76% female) diagnosed with SZ or schizoaffective disorder. This dataset includes a T1-weighted magnetization prepared–rapid gradient echo (MP-RAGE) sequence (repetition time = 1.9 s, echo time = 2.26 ms, field-of-view = 250 mm, matrix = 256 × 256, slice thickness = 1 mm, 176 slices), as well as cognitive behavioral data from the task-switching test. For details on the dataset, see ref. 48. For all MRI analyses, open source code was used. The MP-RAGEs were corrected for B0/B1 inhomogeneities using the N4 algorithm. A study-specific template of the MP-RAGE scans was created in the common space between the scans with an iterative diffeomorphic warp estimate using the ANTS package49. The template was diffeomorphically registered to the MarsAtlas50. A segmentation of the dlPFC was extracted from the atlas and projected to each individual scan. The dlPFC regions of interest were corrected at the individual level with a gray-matter mask made with FSL-FAst and the output was visually verified. The average MP-RAGE signal in the dlPFC gray matter of SZ patients and controls was examined. Two linear models were fitted including the average left and right gray-matter dlPFC MP-RAGE signal as the dependent variable and age, sex and group as the independent variables. A retrospective motion-estimate (Average Edge Strength) was also calculated with the homonymous Matlab toolbox51 and entered as an independent variable. The analyses were repeated for data acquired at both 3T scanners (Trio, Siemens Healthineers). We then utilized a linear model to analyze the correlation between dlPFC gray-matter MP-RAGE signal and accuracy in the task-switching test in SZ patients accounting for age and motion. For details on the task-switching test, see ref. 48. Individual data points and means were plotted using Graphpad Prism 4. Researchers were blinded for disease state during data analysis.

Results

RNA sequencing reveals LXR/RXR activation as the top-enriched canonical pathway in gray matter of SZ dlPFC

RNA sequencing was performed on gray matter from dlPFC of four SZ patients and four controls (see Supplementary Table S2 for subject and tissue characteristics). Gene expression density was similar for all samples (Supplementary Fig. S1a) and differential expression analysis showed 132 significantly upregulated genes and 5 significantly down-regulated genes in SZ dlPFC gray matter (Supplementary Fig. S1b). Ingenuity pathway analysis of the significantly differentially expressed genes revealed that “LXR/RXR activation” was the most significantly enriched canonical pathway in the dlPFC of SZ patients (p = 3.89E-07 in Benjamini–Hochberg corrected T-test; see Table 1 for the top five canonical pathways with statistical values and molecules involved); the other canonical pathways were at least 30 times less enriched. The LXR/RXR pathway regulates cholesterol homeostasis in the brain. The increased abundance of transcripts that are associated with activation of the LXR/RXR pathway indicates a change in cholesterol metabolism in SZ dlPFC gray matter.

Table 1.

Ingenuity pathway analysis of genes differentially expressed in SZ vs. control dlPFC gray matter.

| Canonical pathway | p-value (Benjamini–Hochberg corrected) | Genes |

|---|---|---|

| LXR/RXR activation | 3.89E − 07 | AGT, APOC2, C4A/C4B, IL1RL1, S100A8, SERPINA1, TNFRSF11B |

| Complement system | 1.15E − 05 | C1QA, C1QB, C1QC, C4A/C4B |

| Antigen presentation pathway | 1.43E − 05 | HLA-DMA, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DRB3, HLA-DRB5 |

| PD1-PD-L cancer immunotherapy pathway | 5.45E − 05 | HLA-DMA, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DRB3, HLA-DRB5, TNFRSF11B |

| T-helper cell differentiation | 1.71E − 04 | HLA-DMA, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DRB5, TNFRSF11B |

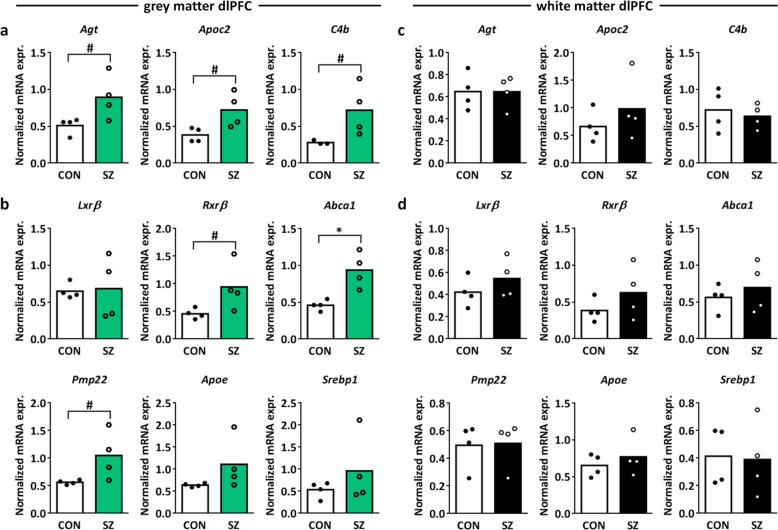

Upregulation of the “LXR/RXR activation” canonical pathway components angiotensinogen (Agt), apolipoprotein C2 (Apoc2), and complement 4b (C4b) in SZ vs. control dlPFC gray matter was confirmed by qPCR (Fig. 1a; independent samples T-test t = 2.407, p = 0.053, df = 6, t = 2.673, p = 0.056, df=3.986, t = 2.155, p = 0.083, df=3.059, respectively; see Supplementary Table S1 for primer sequences). We next investigated whether other mRNAs related to LXR/RXR activation were also differentially expressed in SZ dlPFC gray matter. LXRβ is the isoform of LXR that is expressed most abundantly in the brain and forms heterodimers with RXRβ52. We found an upregulation of Rxrβ, but no changes in the mRNA expression of Lxrβ in the SZ dlPFC gray matter as compared to controls (Fig. 1b; independent samples T-test Rxrβ t = 2.202, p = 0.070, df = 6, Lxrβ t = 0.156, p = 0.885, df = 3.378). The LXRβ/RXRβ pathway activates the transcription factor sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (e.g., SREBP1) and as such stimulates cholesterol and oxysterol efflux from the cell via ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (Abca1), which is regulated by peripheral myelin protein 22 (Pmp22)52–54. Upon efflux from the cell, cholesterol is packed in the brain in high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-like particles containing apolipoproteins, predominantly apolipoprotein E (ApoE)52. Abca1 and Pmp22, but not Srebp1 and Apoe, mRNA expression were upregulated in SZ vs. control dlPFC gray matter (Fig. 1b; independent samples T-test Srebp1 t = 1.047, p = 0.335, df = 6, Apoe t = 1.606, p = 0.206, df = 3.032, Abca1 t = 3.836, p = 0.023, df = 3.538, Pmp22 t = 2.219, p = 0.068, df = 6), indicating increased cholesterol efflux in SZ dlPFC gray matter. Notably, in the dlPFC white matter, no changes in LXR/RXR-related mRNA expression were found (Fig. 1c, d), highlighting the importance of studying mRNA expression patterns in the gray and white matter separately.

Fig. 1. Expression of LXR/RXR-related mRNAs in SZ vs. control dlPFC gray and white matter.

a Normalized mRNA expression of angiotensinogen (Agt), apolipoprotein C2 (Apoc2), and complement 4b (C4b) in SZ vs. control dlPFC gray matter. These mRNAs are components of the canonical pathway “LXR/RXR activation” in the Ingenuity pathway analysis. b Normalized mRNA expression of the LXR/RXR signaling cascade components Liver X receptor β (Lxrβ), retinoid X receptor β (Rxrβ), ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (Abca1), peripheral myelin protein 22 (Pmp22), apolipoprotein E (ApoE), and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1) in SZ vs. control dlPFC gray matter. c, d Normalized mRNA expression of the same genes as in a and b in the white matter of dlPFC. n = 4 samples per group, #p < 0.1, *p < 0.05 in independent samples T-test.

In addition to the LXR/RXR activation pathway, the canonical pathway analysis revealed significant enrichment of four immune-related pathways in SZ dlPFC gray matter (Table 1), in line with the dysregulation of mRNA expression of genes related to inflammation and the immune system in SZ PFC25,38. Furthermore, the top upstream regulator in the Ingenuity pathway analysis was interferon-γ (Supplementary Table S3; p = 2.22E − 16) and this and other proinflammatory cytokines are associated with SZ55–57.

Shared genetic etiology between SZ and lipid metabolism

To further investigate the role of lipid metabolism in SZ, we analyzed the shared genetic etiology between SZ and 514 circulating metabolites, including amino acids, nutrients, organic compounds, cytokines, growth factors, and lipids. Following Bonferroni correction (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S4), we found significant overlap between genetic risk for SZ and 35 metabolites (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S4; p < 0.05) using the results of the 2018 SZ GWAS study published by the Bipolar and Schizophrenia working group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium39. Using a second 2014 SZ GWAS dataset provided by the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium40, the genetic association between SZ risk and 25 of the 35 metabolites was replicated, and 21 additional metabolites that share genetic etiology with SZ were identified (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S5). Strikingly, the 56 metabolites that share significant genetic etiology with SZ are all related to lipids (except for IP10 and IL16) and fall within three themes: acylcarnitines, VLDL lipids, and fatty acid metabolites. We conclude that disruptions in lipid homeostasis are genetically associated with SZ. The finding that two immune-related metabolites IP10 and IL16 (Table 2) share genetic etiology with SZ is in line with the involvement of the immune system in the disorder.

Table 2.

Metabolites that share significant genetic etiology with SZ.

| Metabolite | Lowest significant p-value treshold | Bonferroni- corrected p-value | Lowest significant p-value treshold | Bonferroni- corrected p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SZ GWAS 201840 | SZ GWAS 201448 | |||

| C5.1.DC1 | 0.1 | 0.000246 | 0.05 | 0.015176 |

| IP105 | 0.3 | 0.000997 | 0.05 | 0.048767 |

| CH2.DB.ratio2 | 0.1 | 0.00153 | 0.1 | 0.014121 |

| LPE16_0_LIPID4 | 0.001 | 0.001988 | 0.001 | 0.000768 |

| XS.VLDL.TG3 | 0.2 | 0.002406 | 0.3 | 0.039835 |

| C14.1.OH1 | 0.05 | 0.002534 | 0.05 | 0.008502 |

| DB.in.FA2 | 0.1 | 0.003962 | 0.1 | 0.010729 |

| XS.VLDL.P3 | 0.3 | 0.004685 | 0.2 | 0.008044 |

| IDL.C3 | 0.05 | 0.006454 | NA | NA |

| PC38_2_LIPID4 | 0.3 | 0.007062 | 0.2 | 0.000573 |

| CH2.in.FA2 | 0.2 | 0.008944 | 0.1 | 0.006678 |

| Bis.DB.ratio2 | 0.2 | 0.009453 | 0.05 | 0.018628 |

| DHA2 | 0.4 | 0.010114 | 0.05 | 0.00935 |

| SM.C26.04 | 0.1 | 0.010245 | 0.05 | 0.002634 |

| XS.VLDL.L3 | 0.05 | 0.010881 | 0.2 | 7.49E-05 |

| TAG54_6_LIPID4 | 0.001 | 0.016009 | 0.001 | 0.009793 |

| SM.OH.C24.14 | 0.1 | 0.017865 | 0.05 | 0.006078 |

| FAw34 | 0.05 | 0.01807 | 0.05 | 0.002175 |

| fumarate_maleate_valerat_CMH | 0.05 | 0.019523 | 0.05 | 0.001032 |

| Ratio_PC3806_LPC2206_LIPID4 | 0.05 | 0.023256 | NA | NA |

| IDL.FC3 | 0.4 | 0.024663 | NA | NA |

| LPC20_3_LIPID4 | 0.3 | 0.026304 | NA | NA |

| XS.VLDL.PL3 | 0.05 | 0.027834 | 0.2 | 0.00178 |

| XL.VLDL.TG3 | 0.3 | 0.032077 | 0.3 | 0.001178 |

| PC32_0_LIPID4 | 0.1 | 0.032928 | 0.1 | 0.000627 |

| PC.ae.C44.34 | 0.1 | 0.034516 | NA | NA |

| IDL.L3 | 0.1 | 0.034726 | NA | NA |

| S.VLDL.C3 | 0.4 | 0.035649 | 0.4 | 0.047852 |

| IDL.P3 | 0.1 | 0.036891 | NA | NA |

| lysoPC.a.C20.44 | 0.3 | 0.039526 | 0.2 | 0.019734 |

| Bis.FA.ratio2 | 0.1 | 0.040777 | 0.05 | 0.005426 |

| S.VLDL.L3 | 0.5 | 0.0408 | NA | NA |

| GROa | 0.001 | 0.042828 | NA | NA |

| MCP1 | 0.001 | 0.045366 | 0.001 | 0.001432 |

| LPC22_6_LIPID4 | 0.1 | 0.048797 | NA | NA |

| Cit | NA | NA | 0.05 | 0.00031 |

| PCB36_4_LIPID4 | NA | NA | 0.05 | 0.000894 |

| PC38_6_LIPID4 | NA | NA | 0.1 | 0.002651 |

| CE20_5_LIPID3 | NA | NA | 0.2 | 0.002948 |

| TAG56_6_LIPID4 | NA | NA | 0.2 | 0.005974 |

| PC40_6_LIPID4 | NA | NA | 0.3 | 0.008719 |

| PC.aa.C24.04 | NA | NA | 0.1 | 0.010428 |

| TAG56_8_LIPID4 | NA | NA | 0.2 | 0.012203 |

| IL165 | NA | NA | 0.05 | 0.01252 |

| TAG58_10_LIPID4 | NA | NA | 0.3 | 0.014247 |

| TAG56_6_LIPID4 | NA | NA | 0.3 | 0.020381 |

| XXL.VLDL.PL3 | NA | NA | 0.3 | 0.027232 |

| L.VLDL.P3 | NA | NA | 0.05 | 0.030895 |

| XL.HDL.L3 | NA | NA | 0.5 | 0.032042 |

| aconitate_CMH | NA | NA | 0.1 | 0.032102 |

| XL.VLDL.L3 | NA | NA | 0.4 | 0.03703 |

| TAG58_11_LIPID4 | NA | NA | 0.3 | 0.037887 |

| PC38_4_LIPID4 | NA | NA | 0.4 | 0.038142 |

| LDL.D3 | NA | NA | 0.001 | 0.042824 |

| FAw64 | NA | NA | 0.05 | 0.044601 |

| ADP_CMH | NA | NA | 0.4 | 0.049512 |

1Acylcarnitines.

2Fatty acids.

3Cholesterols.

4Other lipids.

5Immune-related cytokines.

Lipid content of dlPFC gray matter is lower in SZ than in controls and correlates with reduced accuracy in the task-switching test

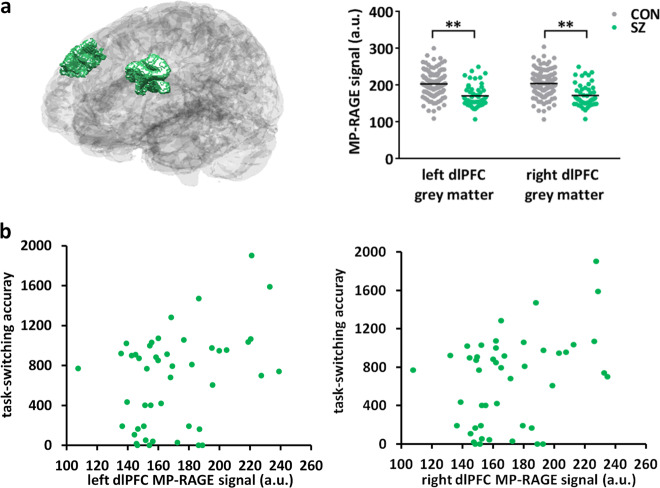

We further investigated the effect of the disrupted lipid homeostasis in SZ dlPFC gray matter using a publicly available dataset from the Consortium for Neuropsychiatric Phenomics. This dataset contains amongst others structural MRI scans and performance in the task-switching cognitive test of 50 SZ patients and 125 control individuals48. From this dataset, we analyzed the T1-weighted MP-RAGE signal. The macromolecular pool in the brain consists mainly of lipids, as illustrated by the typical gray–white matter contrast obtained in T1-weighted MRI scans. The T1 inversion pulse saturates the free-water pool and the macromolecule pool. Following the saturation, the macromolecular pool quickly relaxes and subsequently accelerates the relaxation of the free-water pool in a process termed magnetization transfer. We hypothesized that a difference in lipid content and thus macromolecular pool would contribute to a change in magnetization transfer. We tested this by comparing the dlPFC gray-matter MP-RAGE signal between SZ patients and controls. We found that the MP-RAGE signal was significantly decreased in the dlPFC gray matter of SZ patients as compared to controls, both in the left and right hemispheres, and accounting for age, sex, motion, and scanning site (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table S6; linear model left dlPFC estimate = −26.025, t = −4.433, p < 0.001, right dlPFC estimate = −25.249, t = −4.319, p < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. S2). These results are in accordance with a lower macromolecular content and thus a lower lipid content of the SZ dlPFC gray matter. Notably, we found a correlation between the accuracy on the dlPFC-dependent task-switching test and the MP-RAGE signal in both the left and right dlPFC accounting for age and motion (Fig. 2b; linear model left dlPFC estimate = 4.286, t = 1.946, p = 0.0579, right dlPFC estimate = 4.330, t = 1.969, p = 0.0551). These data are consistent with a lower lipid content of the SZ dlPFC gray matter that correlates with a reduced accuracy in the dlPFC-dependent task-switching test and as such is in line with an important role for a distorted lipid metabolism in the cognitive deficits of SZ.

Fig. 2. MP-RAGE signal in SZ and control dlPFC gray matter and correlation with task-switching accuracy.

a Left: schematic representation of the dlPFC gray matter in the left and right brain hemispheres. Right: average MP-RAGE signal from the left and right dlPFC gray matter in SZ versus control (CON). **p < 0.001 in a linear model corrected for sex, age, motion, and scanning site. b Scatter plot of the accuracy in the task-switching test and the MP-RAGE signal from the dlPFC gray matter in the left and right hemisphere of SZ patients.

Discussion

SZ is a psychiatric disorder with an unknown etiology and its cognitive deficits are associated with the dlPFC. Here we performed RNA sequencing of post-mortem dlPFC gray matter of SZ patients and controls to gain insight into the molecular mechanisms contributing to the cognitive dysfunction in SZ. We found an enrichment of differentially expressed genes in the LXR/RXR activation pathway and validated upregulation of components of the LXR/RXR lipid metabolism pathway in SZ dlPFC gray, but not white, matter. We further revealed shared genetic etiology between SZ and a number of lipid-related metabolites, confirming a genetic link between SZ and lipid metabolism. Finally, the results obtained with the MP-RAGE signals from structural MRI data are in accordance with a decreased lipid content in the dlPFC gray matter of SZ patients and correlated with reduced performance in the task-switching cognitive test.

Gray and white matter have a different cellular composition and function, and distinct transcriptomes33. Gray matter of the cortex consists mainly of neurons and glial cells, while white matter consists primarily of myelinated axons. Previous RNA-sequencing studies on mixes of gray and white matter from the dlPFC of SZ patients and controls have shown among others altered abundance of transcripts involved in glucocorticoid signaling29, presynaptic function32, inflammation25, nuclear receptor signaling23, synaptic vesicle recycling, transmitter release, and cytoskeletal dynamics31. Our RNA-sequencing study on only the dlPFC gray matter confirms the dysregulation of inflammation-related genes in SZ. More importantly, among the differentially expressed dlPFC gray-matter genes the most enriched pathway involved LXR/RXR-mediated cholesterol lipid homeostasis. LXR/RXR-related genes were upregulated in the dlPFC gray matter of SZ patients, but were unaltered in the dlPFC white matter. The previous transcriptomic studies on a mix of SZ dlPFC gray and white matter have likely missed the enrichment of this pathway because of the relatively high contribution of the lipid content of the white matter.

Interestingly, dlPFC gray-matter mRNA expression differences in the axon guidance pathway are known to exist between controls and SZ patients with auditory hallucinations, but not between controls and SZ patients without auditory hallucinations36. This highlights that mRNA expression in dlPFC gray matter might differ among subgroups of SZ patients. As in the present study we did not compare subgroups of SZ patients, we may have missed more subtle mRNA expression differences between patients and controls. In addition, for unknown reasons we did not find the previously reported decreased mRNA expression of the SZ-associated DEGS2 gene in SZ dlPFC gray matter37 nor the decreased expression of sodium channel subunit SCN2A, the latter probably due to the fact that we studied a different PFC subregion34. Thus, future transcriptomic studies should include SZ patient subgroups and various PFC subregions.

The LXR/RXR pathway is activated by binding of oxysterols to LXR. Oxysterols are metabolites produced during the breakdown of cholesterol and able to cross the blood brain barrier. In the brain, LXRβ forms heterodimers with RXRβ and their activation leads to increased efflux of cholesterol via ABCA1- and PMP22-regulated mechanisms into HDL-like particles containing apolipoprotein, inhibition of cholesterol uptake by the cell and stimulation of fatty acid synthesis52–54. We indeed found moderate upregulation of Rxrβ, Apoc2, Abca1, and Pmp22 in SZ dlPFC gray matter as compared to controls. Interestingly, LXR signaling is involved in the development of ventral midbrain dopaminergic neurons52,58 and there is a genetic association between PMP22 and SZ59. In vitro studies have shown contradictory effects of antipsychotics on LXR signaling in that one study has reported an increased mRNA expression of Abca1 and Apoe60, whereas a second study has shown that antipsychotics reduce cholesterol synthesis and export from the endoplasmic reticulum, and do not induce LXR activation61. Nevertheless, a disturbance of LXR-mediated cholesterol homeostasis appears to play a role in SZ etiology, but further studies are necessary.

A number of links exist between a distorted lipid homeostasis and SZ. For example, a meta-analysis has revealed that metabolic syndrome in SZ patients, a condition in which cholesterol and triglyceride levels are abnormal, is associated with a high degree of cognitive impairment62. Metabolic syndrome also impairs cognition in otherwise healthy individuals63. Blood triglyceride levels are correlated with positive symptom severity and blood HDL levels with global functioning of SZ patients64. Unmedicated SZ patients have lower total cholesterol, HDL, and apolipoprotein levels64,65, and lower short-chain acylcarnitine levels in the blood66. Moreover, in SZ patients using antipsychotic medication the occurrence of metabolic syndrome is increased and cholesterol levels are correlated with cognitive impairment63,67, implicating a role for peripheral lipid metabolism in brain functioning and cognitive deficits in SZ. In the present study, we find that SZ shares genetic etiology with a number of metabolites, most of which were replicated using a second SZ GWAS study. Among the metabolites that share genetic etiology with SZ, we found an enrichment of acylcarnitines, VLDL lipids and fatty acid metabolites. A previous polygenic risk score analysis has revealed that the severity of cognitive deficits is linked to genetic variations in genes involved in retinoid signaling68, a pathway that, similar to the LXR/RXR pathway, is linked to lipid metabolism. Therefore, our results together with this earlier finding highlight a genetic contribution to the observed alterations in lipid homeostasis in SZ that are thus likely not solely caused by antipsychotic treatment.

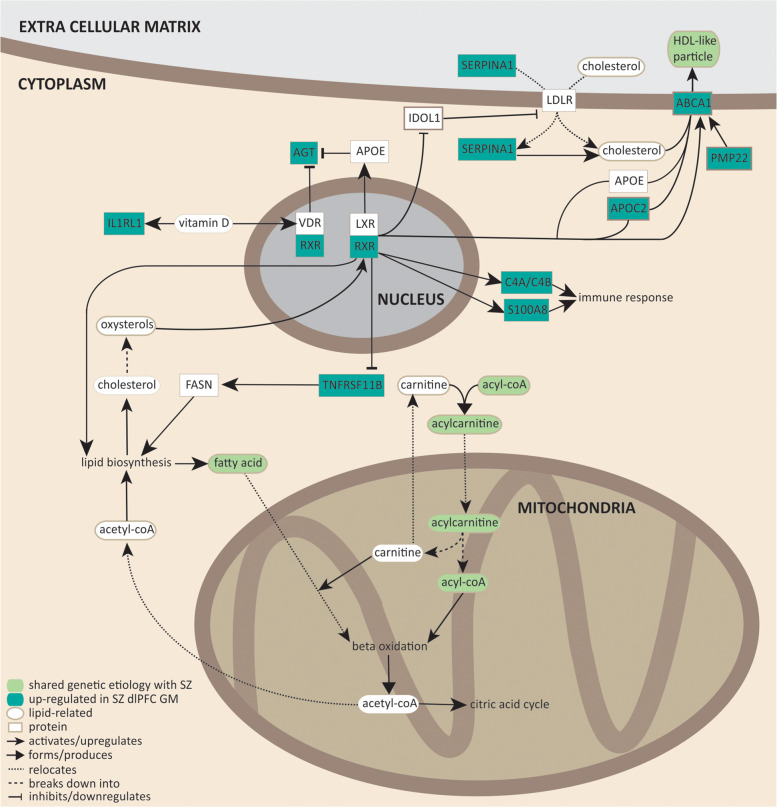

Notably, acylcarnitines, fatty acid production, cholesterol efflux into HDL-like particles, and LXR/RXR activation share a common molecular pathway (Fig. 3). During fatty acid oxidation, unsaturated fatty acids esterify with acyl-CoA to form acylcarnitine that is subsequently transported into the mitochondrial inner membrane. Once inside the inner mitochondrial membrane, acylcarnitines are subjected to β-oxidation, which produces acetyl-CoA that can either enter the citric acid cycle, or is transported to the cytosol where it participates in lipid biosynthesis (fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis). Cholesterol can be transported out of the cell via HDL-like particles. Based on our transcriptomic study and the shared genetic etiology between SZ and several lipid-related metabolites, we conclude that lipid homeostasis involving fatty acid oxidation and cholesterol efflux, production, and transport may well play a role in SZ.

Fig. 3. Molecular pathways involving LXR/RXR signaling, acylcarnitines, VLDL lipids, and fatty acid metabolites.

Dark green rectangles represent genes upregulated in SZ dlPFC. Light green ovals represent lipid-related metabolites that share significant genetic etiology with SZ. Arrows indicate the nature of molecular interactions (see legend in the figure for details). References54,68,84–94 have been used to construct the molecular pathways.

Using a publicly available dataset48, we show that the T1-weighted MP-RAGE signal is significantly decreased in SZ dlPFC gray matter. The T1-weighted MP-RAGE signal creates contrast between gray and white matter, which is thought to be due to magnetization transfer effects, where increased lipid content results in increased signal. Our results are therefore consistent with a decreased lipid content in the gray matter of the dlPFC of SZ patients. This conclusion does not take into account the added effects from differences in spin density or in the relaxation rate of the free-water pool itself to the MP-RAGE signal. However, the relaxation rate of the free-water pool itself is largely homogeneous across the brain69,70. Our finding of a decreased lipid content in SZ dlPFC gray matter thus warrants future validation with quantitative magnetization transfer methods. Notably, the decreased MP-RAGE signal in SZ dlPFC gray matter correlates with decreased accuracy in the task-switching test in SZ patients. The task-switching test examines executive functioning and relies on the dlPFC71–73. In SZ patients, reduced accuracy74 and reaction time differences75 in this test have been reported. We find that in SZ altered performance in the task-switching test might arise from a decreased lipid content in the dlPFC.

About half of the dry weight of the brain is attributable to lipids and about 80% of brain lipids are part of myelin sheaths. In SZ PFC, abnormalities in myelination are evident and decreased PFC myelin content contributes to disease symptomatology76,77. Furthermore, polyunsaturated fatty acid levels in the blood are correlated with white-matter integrity in frontal regions of the SZ brain78, whereas increased LDL levels are associated with white-matter alterations79, and white matter, as well as myelin abnormalities in the PFC contribute to cognitive deficits in SZ76. Myelin lipids are produced by oligodendrocytes (OLs) and LXRβ-knockout mice show a hypomyelination phenotype, because cholesterol deficiency inhibits OL differentiation and myelination80,81. During brain development, LXRβ is also involved in the formation of OL precursor cells82 and exerts transcriptional control over myelin-related genes83. Therefore, abnormalities in LXR signaling likely contribute to myelin deficits in SZ PFC.

Taken all findings together, we conclude that LXR-driven disturbances in lipid homeostasis are associated with SZ and may mediate the myelination deficits, and as such contribute to the etiology of the cognitive symptoms of SZ.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the program “Top talent” Donders Centre for Medical Neuroscience (to D.A.M.) and a Van Gogh travel grant (to D.A.M., B.N.O., and G.J.M.M.).

Author contributions

D.A.M. and G.J.M.M. designed the project and wrote the manuscript. D.A.M. performed data acquisition and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. W.A.Z. performed data acquisition of RNA sequencing and qPCR experiments. M.B.M. performed data analysis of shared genetic etiology, N.P. performed data analysis of structural MRI data. J.R.H. and B.N.O. contributed to supervision of the project. G.J.M.M. supervised the project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41398-020-01084-x).

References

- 1.Modai S, Shomron N. Molecular risk factors for schizophrenia. Trends Mol. Med. 2016;22:242–253. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tandon R, Nasrallah HA, Keshavan MS. Schizophrenia, “just the facts” 4. Clinical features and conceptualization. Schizophrenia Res. 2009;110:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arndt S, Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Miller D, Nopoulos P. A longitudinal study of symptom dimensions in schizophrenia. Prediction and patterns of change. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1995;52:352–360. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950170026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fioravanti M, Carlone O, Vitale B, Cinti ME, Clare L. A meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in adults with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2005;15:73–95. doi: 10.1007/s11065-005-6254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis R. Should cognitive deficit be a diagnostic criterion for schizophrenia? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2004;29:102–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gold JM, et al. Selective attention, working memory, and executive function as potential independent sources of cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 2018;44:1227–1234. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reichenberg A, Harvey PD. Neuropsychological impairments in schizophrenia: Integration of performance-based and brain imaging findings. Psychol. Bull. 2007;133:833–858. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel KR, Cherian J, Gohil K, Atkinson D. Schizophrenia: overview and treatment options. P T. 2014;39:638–645. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bloemen OJ, et al. White-matter markers for psychosis in a prospective ultra-high-risk cohort. Psychol. Med. 2010;40:1297–1304. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamminga CA, Buchanan RW, Gold JM. The role of negative symptoms and cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia outcome. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1998;13(Suppl 3):S21–S26. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199803003-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hintze B, Borkowska A. Associations between cognitive function, schizophrenic symptoms, and functional outcome in early-onset schizophrenia with and without a familial burden of psychosis. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2015;52:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhagyavathi HD, et al. Cascading and combined effects of cognitive deficits and residual symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia - a path-analytical approach. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229:264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joseph J, et al. Predictors of current functioning and functional decline in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Res. 2017;188:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mollon J, Reichenberg A. Cognitive development prior to onset of psychosis. Psychol. Med. 2018;48:392–403. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717001970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gkintoni E, Pallis EG, Bitsios P, Giakoumaki SG. Neurocognitive performance, psychopathology and social functioning in individuals at high risk for schizophrenia or psychotic bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2017;208:512–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manoach DS. Prefrontal cortex dysfunction during working memory performance in schizophrenia: reconciling discrepant findings. Schizophrenia Res. 2003;60:285–298. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo JY, Ragland JD, Carter CS. Memory and cognition in schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 2019;24:633–642. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0231-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ragland JD, et al. Cognitive control of episodic memory in schizophrenia: differential role of dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015;9:604. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shad MU, Muddasani S, Keshavan MS. Prefrontal subregions and dimensions of insight in first-episode schizophrenia–a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2006;146:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lesh TA, et al. Proactive and reactive cognitive control and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex dysfunction in first episode schizophrenia. NeuroImage. Clin. 2013;2:590–599. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoon JH, et al. Association of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex dysfunction with disrupted coordinated brain activity in schizophrenia: relationship with impaired cognition, behavioral disorganization, and global function. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008;165:1006–1014. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07060945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramaker RC, et al. Post-mortem molecular profiling of three psychiatric disorders. Genome Med. 2017;9:72. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0458-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corley SM, Tsai SY, Wilkins MR, Shannon Weickert C. Transcriptomic analysis shows decreased cortical expression of NR4A1, NR4A2 and RXRB in schizophrenia and provides evidence for nuclear receptor dysregulation. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0166944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tao R, et al. GAD1 alternative transcripts and DNA methylation in human prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in brain development, schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 2018;23:1496–1505. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fillman SG, et al. Increased inflammatory markers identified in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 2013;18:206–214. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birnbaum R, et al. Investigating the neuroimmunogenic architecture of schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 2018;23:1251–1260. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis KN, et al. GAD2 alternative transcripts in the human prefrontal cortex, and in schizophrenia and affective disorders. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0148558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hauberg, M. E. et al. Differential activity of transcribed enhancers in the prefrontal cortex of 537 cases with schizophrenia and controls. Mol. Psychiatry, 10.1038/s41380-018-0059-8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Sinclair D, Fillman SG, Webster MJ, Weickert CS. Dysregulation of glucocorticoid receptor co-factors FKBP5, BAG1 and PTGES3 in prefrontal cortex in psychotic illness. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:3539. doi: 10.1038/srep03539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shao L, Vawter MP. Shared gene expression alterations in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;64:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maycox PR, et al. Analysis of gene expression in two large schizophrenia cohorts identifies multiple changes associated with nerve terminal function. Mol. Psychiatry. 2009;14:1083–1094. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mirnics K, Middleton FA, Marquez A, Lewis DA, Levitt P. Molecular characterization of schizophrenia viewed by microarray analysis of gene expression in prefrontal cortex. Neuron. 2000;28:53–67. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mills JD, et al. Unique transcriptome patterns of the white and grey matter corroborate structural and functional heterogeneity in the human frontal lobe. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dickinson D, et al. Differential effects of common variants in SCN2A on general cognitive ability, brain physiology, and messenger RNA expression in schizophrenia cases and control individuals. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:647–656. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hawrylycz MJ, et al. An anatomically comprehensive atlas of the adult human brain transcriptome. Nature. 2012;489:391–399. doi: 10.1038/nature11405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilabert-Juan J, et al. Semaphorin and plexin gene expression is altered in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenia patients with and without auditory hallucinations. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229:850–857. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohi K, et al. DEGS2 polymorphism associated with cognition in schizophrenia is associated with gene expression in brain. Transl. Psychiatry. 2015;5:e550–e550. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saetre P, et al. Inflammation-related genes up-regulated in schizophrenia brains. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Genomic Dissection of Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia. Including 28 subphenotypes. Cell. 2018;173:1705–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Consortium SWGOTPG. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rhee EP, et al. A genome-wide association study of the human metabolome in a community-based cohort. Cell Metab. 2013;18:130–143. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Draisma HHM, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel genetic variants contributing to variation in blood metabolite levels. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7208. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kettunen J, et al. Genome-wide study for circulating metabolites identifies 62 loci and reveals novel systemic effects of LPA. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11122. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahola-Olli AV, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 27 loci influencing concentrations of circulating cytokines and growth factors. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;100:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Euesden J, Lewis CM, O’Reilly PF. PRSice: Polygenic Risk Score software. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1466–1468. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson, T. gtx: Genetics ToolboX. R package version 0.0.8. (2013).

- 47.Auton A, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poldrack RA, et al. A phenome-wide examination of neural and cognitive function. Sci. data. 2016;3:160110. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Avants BB, et al. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. NeuroImage. 2011;54:2033–2044. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Auzias G, Coulon O, Brovelli A. MarsAtlas: a cortical parcellation atlas for functional mapping. Hum. brain Mapp. 2016;37:1573–1592. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zaca D, Hasson U, Minati L, Jovicich J. Method for retrospective estimation of natural head movement during structural MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2018;48:927–937. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Courtney R, Landreth GE. LXR regulation of brain cholesterol: from development to disease. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2016;27:404–414. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J. Clin. Investig. 2002;109:1125–1131. doi: 10.1172/JCI0215593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou Y, et al. PMP22 regulates cholesterol trafficking and ABCA1-mediated cholesterol rfflux. J. Neurosci. 2019;39:5404–5418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2942-18.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jemli A, et al. Association of the IFN-gamma (+874A/T) genetic polymorphism with paranoid schizophrenia in Tunisian population. Immunol. Investig. 2017;46:159–171. doi: 10.1080/08820139.2016.1237523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paul-Samojedny M, et al. Association study of interferon gamma (IFN-gamma) +874T/A gene polymorphism in patients with paranoid schizophrenia. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2011;43:309–315. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9442-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Na KS, Jung HY, Kim YK. The role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the neuroinflammation and neurogenesis of schizophrenia. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. psychiatry. 2014;48:277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Theofilopoulos S, et al. Brain endogenous liver X receptor ligands selectively promote midbrain neurogenesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013;9:126–133. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Endres, D. et al. Schizophrenia and hereditary polyneuropathy: PMP22 deletion as a common pathophysiological link? Front. Psychiatry10, 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00270 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Vik-Mo AO, Ferno J, Skrede S, Steen VM. Psychotropic drugs up-regulate the expression of cholesterol transport proteins including ApoE in cultured human CNS- and liver cells. BMC Pharmacol. 2009;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kristiana I, Sharpe LJ, Catts VS, Lutze-Mann LH, Brown AJ. Antipsychotic drugs upregulate lipogenic gene expression by disrupting intracellular trafficking of lipoprotein-derived cholesterol. Pharmacogenomics J. 2010;10:396–407. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2009.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bora E, Akdede BB, Alptekin K. The relationship between cognitive impairment in schizophrenia and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2017;47:1030–1040. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716003366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.MacKenzie NE, et al. Antipsychotics, metabolic adverse effects, and cognitive function in schizophrenia. Front. psychiatry. 2018;9:622. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Solberg DK, Bentsen H, Refsum H, Andreassen OA. Association between serum lipids and membrane fatty acids and clinical characteristics in patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2015;132:293–300. doi: 10.1111/acps.12388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu X, et al. The comparison of glycometabolism parameters and lipid profiles between drug-naive, first-episode schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Schizophrenia Res. 2013;150:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cao B, et al. Characterizing acyl-carnitine biosignatures for schizophrenia: a longitudinal pre- and post-treatment study. Transl. Psychiatry. 2019;9:19. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0353-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krakowski M, Czobor P. Cholesterol and cognition in schizophrenia: a double-blind study of patients randomized to clozapine, olanzapine and haloperidol. Schizophrenia Res. 2011;130:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reay, W. R. et al. Polygenic disruption of retinoid signalling in schizophrenia and a severe cognitive deficit subtype. Mol. Psychiatry, 10.1038/s41380-018-0305-0 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.van Gelderen P, Jiang X, Duyn JH. Effects of magnetization transfer on T1 contrast in human brain white matter. NeuroImage. 2016;128:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gochberg DF, Gore JC. Quantitative imaging of magnetization transfer using an inversion recovery sequence. Magn. Reson. Med. 2003;49:501–505. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Premereur E, Janssen P, Vanduffel W. Functional MRI in macaque monkeys during task switching. J. Neurosci. 2018;38:10619–10630. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1539-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dove A, Pollmann S, Schubert T, Wiggins CJ, von Cramon DY. Prefrontal cortex activation in task switching: an event-related fMRI study. Brain Res. Cogn. Brain Res. 2000;9:103–109. doi: 10.1016/S0926-6410(99)00029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hyafil A, Summerfield C, Koechlin E. Two mechanisms for task switching in the prefrontal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:5135–5142. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2828-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Greenzang C, Manoach DS, Goff DC, Barton JJ. Task-switching in schizophrenia: active switching costs and passive carry-over effects in an antisaccade paradigm. Exp. Brain Res. 2007;181:493–502. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-0946-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ravizza SM, Moua KC, Long D, Carter CS. The impact of context processing deficits on task-switching performance in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Res. 2010;116:274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maas DA, Valles A, Martens GJM. Oxidative stress, prefrontal cortex hypomyelination and cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1171. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Maas DA, et al. Interneuron hypomyelination is associated with cognitive inflexibility in a rat model of schizophrenia. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2329. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16218-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peters BD, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and brain white matter anisotropy in recent-onset schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Prostagland. Leuk. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2009;81:61–63. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Szeszko PR, et al. White matter changes associated with antipsychotic treatment in first-episode psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:1324–1331. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Saher G, et al. High cholesterol level is essential for myelin membrane growth. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:468–475. doi: 10.1038/nn1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sandoval-Hernandez A, Contreras MJ, Jaramillo J, Arboleda G. Regulation of oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination by nuclear receptors: role in neurodegenerative disorders. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016;949:287–310. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-40764-7_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xu P, et al. Liver X receptor beta is essential for the differentiation of radial glial cells to oligodendrocytes in the dorsal cortex. Mol. Psychiatry. 2014;19:947–957. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Meffre D, et al. Liver X receptors alpha and beta promote myelination and remyelination in the cerebellum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:7587–7592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424951112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Remaley AT, et al. Apolipoprotein specificity for lipid efflux by the human ABCAI transporter. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;280:818–823. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhu R, Ou Z, Ruan X, Gong J. Role of liver X receptors in cholesterol efflux and inflammatory signaling (review) Mol. Med. Rep. 2012;5:895–900. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Longo N, Frigeni M, Pasquali M. Carnitine transport and fatty acid oxidation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1863:2422–2435. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hong C, Tontonoz P. Liver X receptors in lipid metabolism: opportunities for drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:433–444. doi: 10.1038/nrd4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gibbons AS, et al. The neurobiology of APOE in schizophrenia and mood disorders. Front. Biosci. 2011;16:962–979. doi: 10.2741/3729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Martorell S, et al. Vitamin D receptor activation reduces angiotensin-II-induced dissecting abdominal aortic aneurysm in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016;36:1587–1597. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Manna PR, Sennoune SR, Martinez-Zaguilan R, Slominski AT, Pruitt K. Regulation of retinoid mediated cholesterol efflux involves liver X receptor activation in mouse macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;464:312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.06.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pfeffer PE, et al. Vitamin D enhances production of soluble ST2, inhibiting the action of IL-33. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;135:824–827. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Subramaniyam D, et al. Cholesterol rich lipid raft microdomains are gateway for acute phase protein, SERPINA1. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010;42:1562–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Goswami S, Sharma-Walia N. Crosstalk between osteoprotegerin (OPG), fatty acid synthase (FASN) and, cycloxygenase-2 (COX-2) in breast cancer: implications in carcinogenesis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:58953–58974. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Robertson KM, et al. Cholesterol-sensing receptors, liver X receptor alpha and beta, have novel and distinct roles in osteoclast differentiation and activation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2006;21:1276–1287. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.