Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has grossly affected how we deliver health care and how health care institutions derive value from the care provided. Adapting to new technologies and reimbursement patterns were challenges that had to be met by the institutions while patients struggled with decisions to prioritize concerns and to identify new pathways to care. With the implementation of social distancing practices, telemedicine plays an increasing role in patient care delivery, particularly in the field of neurology. This is of particular concern in our cancer patient population given that these patients are often at increased infectious risk on immunosuppressive therapies and often have mobility limitations. We reviewed telemedicine practices in neurology pre– and post–COVID-19 and evaluated the neuro-oncology clinical practice approaches of 2 large care systems, Barrow Neurological Institute and Geisinger Health. Practice metrics were collected for impact on clinic volumes, institutional recovery techniques, and task force development to address COVID-19 specific issues. Neuro-Oncology divisions reached 67% or more of prepandemic capacity (patient visits and slot utilization) within 3 weeks and returned to 90% or greater capacity within 6 weeks of initial closures due to COVID-19. The 2 health systems rapidly and effectively implemented telehealth practices to recover patient volumes. Although telemedicine will not replace the in-person clinical visit, telemedicine will likely continue to be an integral part of neuro-oncologic care. Telemedicine has potential for expanding access in remote areas and provides a convenient alternative to patients with limited mobility, transportation, or other socioeconomic complexities that otherwise challenge patient visit adherence.

Keywords: Barrow Neurological Institute (BNI), COVID-19, Geisinger Health, neuro-oncology, telehealth

History of United States COVID-19 Crisis of 2020

More than 9720 people infected and 213 dead marked the earliest signs of a late December pneumonia outbreak in the Wuhan, Hubei, province of China.1 By January 31, 2020, there would be an additional 106 people in 19 other countries infected, putting the world on high alert.1 A novel coronavirus would be the culprit in causing the disease now known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), while even the most reliable sources debate the origins of this entity now labeled as a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) based on its near 80% homology to the 2002 to 2003 highly fatal SARS-CoV epidemic with patient symptoms compatible with acute respiratory distress syndrome.2

Symptomatic adults have an approximate 14-day incubation period, reliably present with fever and dry cough, and some demonstrate signs of fatigue, myalgias, and dyspnea; however, some patients remain completely asymptomatic.1,3 Chest imaging frequently shows bilateral ground glass opacities in positive cases.3 There has recently been some suggestion of increased stroke or stroke-like presentations, and this continues to be investigated.4,5 Pediatric symptomatology is similar to common upper respiratory tract viral infections but the data are limited in this population, with only 2% of the confirmed US cases involving children younger than 18 years.6

Countries received information about the basic reproduction number (R0), an indicator of the potential for one infected individual to cause new infections in a naive population, calculated by the World Health Organization to range from 1.4 to 2.5 individuals.7 By comparison, R0 estimates for SARS had ranged from 2 to 5.7 Subsequent, more detailed analysis by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) accounting for confounding elements such as reservoir spillover events and low surveillance intensity, however, revealed a much higher R0 of 5.7 for COVID-19.8 For symptomatic patients, quarantining and contact tracing were determined to be the most effective approaches to contain the virus; however, with a suspected 20% of transmission being driven by asymptomatic infected individuals, the CDC recommended social or physical distancing efforts.8

History of Telemedicine in and Challenges in Neurology Clinics

Telemedicine is broadly defined as medicine delivered from a distance, and has been modified over time to better define video vs telephonic and provider-at-home vs patient-at-home encounter types.9 In the COVID-19 era the definition continues to expand because there is a growing need for flexibility in health care delivery, the use of both video and telephonic virtual visits, and the necessity for adjusted reimbursement patterns by insurers. Over the past 20 to 30 years, digital technology has been classified by functionality (consultation, diagnosis, monitoring, and mentoring), application (medical specialty, disease entity, site of care, or treatment modality), and type of technology.9 The expansion was driven primarily by a need to increase access to care for military personnel, prisoners, and rural populations, and has been extended to address the needs of low-income communities.10 Global or regional natural disasters have also motivated the development of telemedicine, as evidenced by the Multinational Telemedicine System program funded by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) from 2013 to 2017.11

Telestroke was one of the earliest applications of synchronous digital telemedicine, developed in 1999 to increase patient access to time-sensitive and neurologic function preserving fibrinolytic therapies after a presumed stroke.10 Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) was approved for stroke in 1996, but had been underused in certain geodemographic regions.12 The institution of telemedicine improved the use of tPA as well as patient outcomes in these areas and expanded to more than 50 networks across the United States within the first decade.12 Remarkably, use of the telestroke system to measure the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale was demonstrated to have a comparable interrater reliability to that of in-person measurements.12

To proceed with a telemedicine visit with video conferencing, internet access and a device with a webcam are required. Examples of HIPAA-compliant audiovisual platforms include Zoom, InTouch, Cisco WebEx, Doxy.me, Thera-LINK, and TheraNest.13,14 With the temporary waiver of HIPAA penalties in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, FaceTime, Google Duo, WhatsApp, Doximity, and Skype are alternative options.15 These technology requirements as well as the need for a private space in which to conduct the visit would pose challenges for the most vulnerable in our society, including the homeless and those unable to afford costly high-tech devices and access to the internet. This has undoubtedly resulted in significant access and health provision disparities along socioeconomic lines. People who are older, live in rural areas, have lower incomes, are less educated, or have more chronic conditions are all less likely to have internet access, with only 58% of people older than 65 years stating that they use the internet.10

Telemedicine in Neurology Subspecialties

While the use of telemedicine in stroke neurology has been well established, there are limited data for telemedicine in other neurological specialties. There have been studies on use in traumatic brain injury, dementia, epilepsy, headache, movement disorders, multiple sclerosis, neuromuscular, and inpatient neurology, although the neuromuscular subspecialty was largely restricted to patients with established diagnoses.16 Reliance of neurologists on the physical exam for the diagnostic process has posed a unique challenge in adapting to this new method.

Although intractable epilepsy may be diagnosed with inpatient continuous EEG monitoring, spell characterization in an epilepsy monitoring unit is considered nonurgent and has been deferred at many institutions, requiring treatment using best clinical judgment.17,18 Additionally, nonurgent epilepsy surgery has also been postponed.17,18 Electrodiagnostic studies and muscle and nerve biopsies for diagnosis of neuromuscular disease, as well as nonurgent treatment with botulinum toxin injections, have also been cancelled, with outpatient pulmonary function tests not always performed because of increased risk. Outpatient physical and occupational therapists tend to see only essential postoperative patients, with the remaining patients sent photographs or videos of exercises. In some regions, delivery of medical equipment such as wheelchairs and Hoyer lifts has been significantly delayed.19

Anecdotally, the fear surrounding the perceived or actual risk of contracting COVID-19 has affected not only the patient’s willingness to present for medical care but also the flexibility of practitioners to treat conditions that are equivocal for emergent need. Given that many cancer patients are on immunosuppressive treatment, they are at particularly increased risk of developing COVID-19 and having poorer outcomes if they were to contract the disease.20 There have been discussions around how standards of care for cancer patients might be modified to limit the risk for COVID-19.21,22 One report from the Hubei province demonstrated a greater than 20% reduction in oncologic and hematologic drugs being administered.23 Several registries, such as COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium and American Society of Hematology, have been developed to capture cancer patients with a COVID-19 diagnosis with a goal to assess patient outcomes and analyze clinical practice in this patient population.24 Telemedicine is likely to play an important role in reducing the risk of exposure in vulnerable populations, particularly in neuro-oncology, for which most oral therapies are prescribed on an outpatient basis. However, many patients may still be required to present to a clinic with special precautions taken to receive chemotherapy infusions or remain compliant with clinical trial protocols.

Caring Through Telemedicine

Telemedicine may seem somewhat impersonal, particularly when engaging in difficult conversations such as providing a new diagnosis of brain tumor or discussing goals of care. Small physical gestures that routinely express sympathy or otherwise comfort the patient such as sitting close, leaning in, or offering a facial tissue are lost.25 Comforting the patient is also a critical component to patient-physician trust and rapport building.26,27 During telemedicine visits, subtle changes in body language, facial expressions, voice intonation, and hand gestures are potentially misinterpreted. Concern for privacy violation and issues of patient mistrust of technology might also play a role and hamper patient-physician communication.25 On the other hand, the convenience of telemedicine may allow for more frequent visits to be scheduled to develop greater rapport. Physicians need to remain cognizant of these issues when meeting with patients via telemedicine. There may also be a resistance to learn new technology, particularly among older patients and more senior providers. Access and optimal use of telemedicine may be limited, particularly for the demographic groups previously described. Telemedicine is also disruptive and complex, demanding that health care providers learn new methods of consultation and requiring operational telemedicine networks, policies and procedures, and technology infrastructure to be put in place.28 Furthermore, limitations on performing the neurological exam may hamper the detection of subtle exam findings that may suggest progression of disease. As providers become more accustomed to the technological variability and the interpersonal etiquette of telemedicine, patient satisfaction will likely continue to improve.

Telemedicine Neurological Examination

Telemedicine has been useful in neurology to minimize the time and costs associated with patient access to critical neurologic care by allowing for rapid video-based assessments and has been of longstanding utility in rural, veteran, and populations with otherwise limited mobility.29 This is an especially useful tool in geographic regions where neurologists are limited and is a growing option used in hospitals, home health agencies, and specialty practices.29,30 While we presume there are measurable differences in the length of time required to complete virtual vs in-person neurological examinations, it is likely highly dependent on the technology used and the experience of the practitioner. Issues in development of workflows and procedural codes might also influence these outcomes in the COVID-19 era.31 To our knowledge, there are no published reports that directly compare this metric in neurology.

Pre-telemedicine visit calls with nursing can be completed to assist with gathering most recent vital signs as available in the chart or completed at home by the patients with access to measuring devices (temperature, blood pressure and weight).

Mental status/language.—A detailed mental status exam can be performed, with components of the Mini-Mental Status Exam or Montreal Cognitive Assessment through screen-sharing techniques and having the patient copy on paper and hold up to the camera.

Speech.—This can be assessed during cognitive assessment through direct observation.

Cranial nerves.—A limited assessment of visual fields and extraocular movements is accomplished with close-range camera visualization, often observing for ptosis and nystagmus simultaneously. Direct observation for facial asymmetry and use of the patient or family members to test and report facial sensory deficits, hearing to finger rub, symmetric head rotation, shoulder shrug, tongue protrusion.

Motor.—This exam has significant limitations because of the inability to precisely measure strength and determine patterns of weakness or assess reflexes and tone. However, some determination can be made by assessing for symmetric movements, downward drift, pronator drift, arm roll, leg drift, squats, toe walk, heel walk, standing from seated position, and fine finger movements. Often the clinician can readily determine focality. Muscle contractures, atrophy, tremor, and involuntary movements may also be noted.

Sensory.—This exam can be reported subjectively or with the assistance of a present family member. Romberg sign may be checked but is difficult for lay people or is risky and often left out of telemedicine exams.

Coordination.—Assessed by instructing the patient to complete finger-to-nose and heel to chin testing.

Gait.—With appropriate space and range of the camera, gait is tested readily. When the patient is using a cell phone for video conferencing and unable to prop up the device, the proper assessment may be difficult to perform. A very limited objective neurological assessment for cognitive, language, speech, and hearing are possible via telephonic medicine visits.

Importantly, we noted that the time required to complete a routine neurological exam via telehealth was extended as compared to the in-person visit. This time was further extended for telehealth visits complicated by slow internet connections and other communication and 2-way video problems between the patient and the provider. Furthermore, patients with hearing or vision deficits, cognitive decline, and poor range of video view (eg, desktop computer camera, cell phone camera) led to extended exam times. We did not formally measure the exam times between virtual and in-person visits, and believe this would be an important metric to capture because it might have implications on clinical scheduling and billing practices.

Dual-Institutional Experiences and Adaptations

Telemedicine Task Force Development

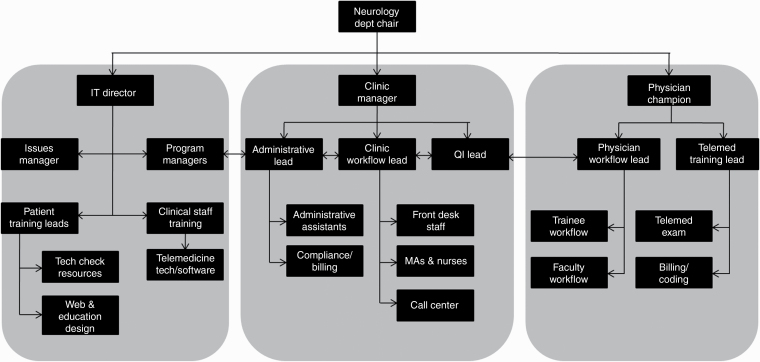

Multiple teams including clinical teams, administrators, business operations, and information technology (Figure 1) worked in tandem to implement a system of telemedicine office visits using Zoom (Barrow Neurological Institute [BNI, Barrow] vs InTouch (Geisinger Health) video communications software. Weekly or daily standing calls were held with the full leadership team to ensure alignment in efforts and to address areas of concern with a broad group to bring more ideas to the table for resolution. Pre-telemedicine calls with nursing and technology support teams helped to preempt technological issues. Robust documentation and training materials were provided for patients, trainers, and staff. Dissemination of educational PowerPoint presentations on HIPAA compliance and proper execution of the neurology telemedicine visit was common between the institutions. Use of uniform “dot” or “smart” phrases and notes that include key points within the billable telemedicine document were provided. Regular check-ins with staff and leadership were implemented for continued optimization of the system. Redeployed personnel from areas of lesser demand during the early phases of the pandemic were helpful to fulfill these responsibilities.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Barrow Neurological Institute Telemedicine Task Force Assigned to Develop a System of Telemedicine Office Visits.

Using Zoom, providers received an email invitation once the appointment was confirmed. Approximately 15 minutes prior to the appointment time, the medical assistant logged into Zoom and completed a review of systems (ROS), medical reconciliation, and pharmacy updates.32 Using InTouch, providers are notified of the patient’s admission into a virtual waiting room, where the provider can click on the “connect” link to initiate the visit.33 Usually, medical assistants or nursing teams perform a final technology check, ROS, medication review, and vital signs the day of the visit prior to the appointment with the provider. In both cases, 2 patient verifiers are used to confirm the patient’s identity and consent for telemedicine visit is obtained.

Telemedicine Billing, Coding, and Reimbursement Prepandemic and Postpandemic

Changes in billing, such as expansion of the list of Medicare-covered telehealth services by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in 2019, have further opened opportunities for teleneurology16 in the home and in the clinical space.

Prior to COVID-19 pandemic, billing, coding, and reimbursement for telemedicine were limited to telemedicine used within the hospital or clinic. Home video visits were not reimbursed by any insurance companies and the outpatient use of hospital or clinic telemedicine was restricted by some payers. Today, patients can benefit from the use of telemedicine by seeing a provider from the safety and comfort of their own home while provider offices can seek reimbursement for services rendered that previously would not have been paid.

In the postpandemic setting, billing, coding, and reimbursement for telemedicine has not been formally decided on yet as a plan for future direction. Currently, the expansion of covered services is still active, and patients can still seek new or established care from their home or the clinical space. What is evolving is the providers’ preference on when and how to use telemedicine. Now that COVID-19–positive cases are decreasing and businesses are opening up, more patients are being seen in person as needed. The use of telemedicine is still fully reimbursable by payers and is being recommended to be permanently mixed in to everyday practice. These decisions will be heavily influenced as payers evaluate their payment models.

Barrow Neurological Institute

BNI has been an internationally renowned center for neurology and neurosurgery since 1962, and has been recognized for having performed the largest number of neurosurgeries annually in the United States. BNI has seen patients from Arizona, neighboring states, and internationally within its 9 Barrow Brain and Spine satellite locations, and employs 5000 faculty and staff across the system. With more than 460 active clinical trials, Barrow is a leader in innovations and was the first institution to offer phase 0 clinical trials for brain tumors. Barrow has 5 residency programs and 12 fellowship programs, has one of the top recognized neurosurgery residency programs nationally, and trains the most brain and spine surgeons of any facility in the United States.

Metrics for Barrow Neurological Institute neuro-oncology ambulatory clinics.—From January 5, 2020 to March 16, 2020, the number of in-person visits ranged from 40 to 65 per week, averaging 54 visits per week. The first telemedicine visit was held March 19, 2020. The number of telemedicine visits per week rapidly increased to 36 visits per week (67% of prepandemic visit capacity) by April 5, 2020 to April 11, 2020, and it reached the prepandemic average by April 19, 2020 to April 25, 2020, with 55 visits per week. By May 1, 2020, the clinic experienced a slightly increase visit numbers above that of the prepandemic visit numbers.

Geisinger Health

Geisinger Health (Geisinger), founded more than 105 years ago, is one of the nation’s largest rural health systems, employing more than 36 000 faculty to staff 15 Geisinger hospital campuses across Central and Northeastern Pennsylvania. With a nearly 4 million-patient catchment area, Geisinger offers primary, secondary, and tertiary care to patients. Geisinger is an academic health institution offering 30 residency programs, 23 fellowship programs, and affiliates with two 4-year colleges. Based on the size of this health care system and its densely rural patient population, use of telemedicine was already well established within particular subspecialties by the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Department of Neurology had been well versed in the use of telemedicine at least 4 years before the pandemic. Platforms for system-wide virtual communications software and provider education were readily activated with minimal need for the development of a formal telemedicine task force.

Metrics for Geisinger Health’s neuro-oncology ambulatory clinics.—We evaluated clinic trends at 2 months prior to the pandemic and for 6 weeks during the early pandemic period (from the time of early state closure and physical distancing recommendation enforcement). We collected the percentage of telemedicine/telehealth visits (both telephonic and televideo) and in-person visits during these times. From January 5, 2020 to March 16, 2020, 100% of patients were billed for in-person visits with an average of 48.5 patients per week (range, 41-60 patients per week) at 93% slot utilization. March 16, 2020, was the first day of telehealth visits. For the first 3 weeks, from March 16 to April 3, 2020, we completed 72 patient visits: 49% (n = 35) in-person visits, and 51% (n = 37) telemedicine visits, averaging 26 patients per week during peak early COVID-19 physical distancing ramp-up. During the second 3-week period (April 6-27), the clinic saw 74 patients (average, 27 patients per week), 12% (n = 9) in person and 88% by telemedicine. By May 2, 2020, 6.5 weeks post–initial closure, the clinic saw an average of 50 patients per week, 90% telemedicine visits and 10% in person, with a 94% slot utilization rate—1% higher than the COVID-19 prepandemic rate. Interestingly, by this time the neuro-oncology subspecialty clinic averaged a better slot utilization overall as compared to the combined neurology department clinics (94% vs 83.3%, respectively) slot utilization. We are currently in the process of evaluating our satisfaction survey reports as supported by Press Ganey Associates to assess the patient experience during telemedicine for the following metrics: (1) ease of scheduling access; (2) care provider professionalism, caring, explanations, and discussion; (3) connectivity and technology issues; and (4) overall assessment and willingness to recommend the services. It is too early to report these data but this will be an important metric to capture.

Comparative Analysis of the Combined Institutional Metrics

A comparative analysis of the 2 institutions’ ambulatory neuro-oncology clinics during the early COVID-19 pandemic period between March 16, 2020 and May 2, 2020, is provided in Table 1. Here we have an overview of the early pandemic ambulatory clinic metrics such as the evaluation period and number of practicing neuro-oncology providers at each institution, and identify each institutions’ patient visit types: (1) new patients/hospital discharges, (2) return patients, and (3) procedural/chemotherapy infusion clinic visits. This information captured the type of patients being seen between the 2 institutions. Barrow’s neuro-oncology clinic routinely sees a larger volume of patients and has twice the number of providers available as compared to Geisinger. We evaluated the percentage of patient visit types to better compare the institutions over a matched time period. Geisinger saw a slightly larger percentage of new/hospital discharge patients as compared to Barrow, whereas Barrow saw a higher percentage of return patients (see Table 1). Overall, however, the trends between the 2 institutions were similar. We note the largest reduction from the pre–COVID-19 period to the early pandemic visit types was for the new patient/hospital discharge postoperative patients for both institutions (data not shown). This is in line with the mandate for limited elective neurosurgical procedures, patient reluctance to present to clinics, and reduction of available hospital beds that was observed nationally during this time.

Table 1.

Comparative Assessment of Patient Clinic Visit Demographics During the Early Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic

| Patient clinic visit demographics during early COVID-19 pandemic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Barrow Neurological Institute (Arizona) | Geisinger Health (Pennsylvania) | |

| COVID-19 observation time frame | March 16, 2020 to May 1, 2020 | March 16, 2020 to May 2, 2020 |

| No. of clinical neuro-oncology providers | 4 | 2 |

| New/hospital discharge neuro-oncology | 8% (n = 30) | 12% (n = 22) |

| Return neuro-oncology (routine follow-up) | 85% (n = 316) | 78% (n = 149) |

| Procedural and chemotherapy infusion clinic visits | 7% (n = 26) | 10% (n = 19) |

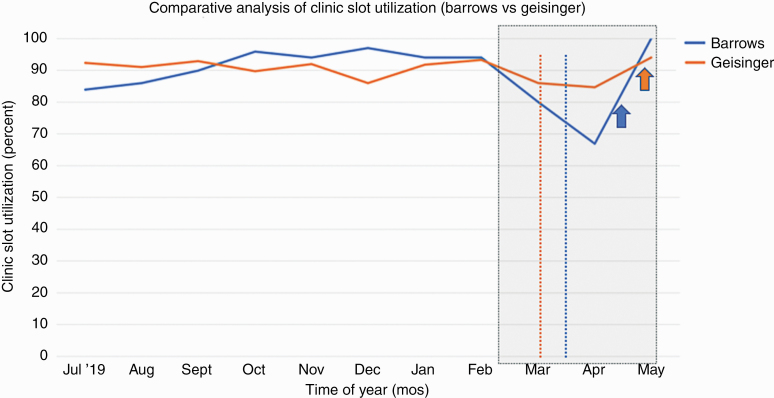

Our respective state closure recommendations were vastly different, with Arizona (Barrow) being delayed by 10 days after Pennsylvania (Geisinger) mandated closures (Figure 2). Early closure by Pennsylvania allowed for earlier transition to telehealth visits, which presumably better matched patient reluctance to present to in-person clinic appointments, thus allowing for Geisinger’s slightly lower reduction in slot utilization during the early pandemic period. Conversely, Arizona reopened earlier than Pennsylvania, thus presumably meeting the increasing demand for more in-person visits—resulting in a near 100% slot utilization by the first week in May. Geisinger achieved a 94% fill rate by this same time. These regional differences likely account for the state-imposed closure and reopening dates. However, Geisinger Health is a large rural integrated health care system that routinely uses telehealth and virtual meetings, thus allowing for a more rapid transition with fewer challenges and less provider educational lag time. On the other hand, Barrow is located in a large metropolitan area and had some prior experience with telemedicine in stroke, movement disorders, and traumatic brain injury clinics—leading to its overall rapid implementation in telehealth in neuro-oncology.

Figure 2.

Comparative Analysis of Clinic Slot Utilization for Barrow Neurological Institute vs Geisinger Health Neuro-Oncology Ambulatory Clinics. The neuro-oncology clinic COVID-19 analysis period between March 16, 2020 to May 2, 2020 (within the gray-shaded rectangle). Neuro-oncology clinic utilization rates for Barrow (blue line) vs Geisinger (orange line) between July 2019 and May 2020. Maximum decline in utilization seen in early April was at 67% (Barrow) and 84% (Geisinger). State closure dates for Barrow/Arizona (blue vertical dashed-line) March 15, 2020 vs Geisinger/Pennsylvania (orange vertical dashed-line) March 5, 2020. State initial reopening dates Barrow/Arizona (blue up arrow) April 15, 2020 vs Geisinger/Pennsylvania (orange up arrow) April 27, 2020. (Dates of closure and reopening as per Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center data.34)

Both institutions experienced an April 2020 decline in slot utilization to approximately 67% (Barrow) and 84% (Geisinger) of prepandemic visit capacity for both institutions (see Figure 2). The state closure date for Barrow/Arizona on March 15, 2020, was later than that for Geisinger/Pennsylvania on March 5, 2020. The state initial reopening date in Barrow/Arizona on April 15, 2020, however, was sooner than that of Geisinger/Pennsylvania on April 27, 2020. These dates of closure and reopening are reported according to Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center data.34

Discussion

Overall Assessment

Implementation of the system was facilitated by quick contracting turnaround, allowing for rapid deployment, as well as quick access to all signatories, which expedited the administrative process. Vocal champions were selected as first users and were an asset for educating providers on using the system. There was efficient redistribution of personnel to help ease the transition, as well as active participation and collaboration of these personnel. A mainstream vendor was used that people know and recognize as easy to use.

Our experiences with telemedicine have demonstrated that much of the neurological exam can be effectively performed using video conferencing. Telehealth offers added benefits for patients because it saves transportation time and costs, especially in cases of routine patient well-checks when critical decision making can be performed virtually. This is also of particular benefit for patients with advanced disease and profound focal neurological deficits that limit their mobility. It also improves efficiency by avoiding delays with rooming patients, because medical assistants do not need to wait for rooms to become vacant. Furthermore, there is potential for expanding catchment area and providing services to patients in remote areas because it eliminates geographical limitations. There is an interesting potential to improve patient outcomes as several studies in cancer care have demonstrated an association between poorer clinical outcomes with increasing distance from the cancer facility.35

Conclusion

There are yet many caveats to telemedicine as part of the clinical practice model; however, it is our impression that telemedicine is here to stay to some extent as a vital complement to the in-person clinic visit. A more permanent integration of the practice models will serve to broaden the scope of the neuro-oncology practice and allow for smoother transition during future crises. As internet access expands and technologies continue to develop, telemedicine is likely to play an increasing role in the delivery of health care across medical specialties and geographic regions to change the way we view and deliver health care.

Funding

No funding support to report for the study included in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the members of the BNI and Geisinger Health COVID-19 Task Forces as well as our respective Clinical Operations teams for their support with data collection and contributions in review of this manuscript. We would like to also acknowledge the late Mr Donald DeGrasse (Teleneuro-Oncology Clinic, BNI), and Mr Jeff Erdly (Geisinger Health) for their program support. Finally, we thank our respective departmental chairs, Dr Jeremy Shefner (BNI) and Dr Neil Holland (Geisinger Health).

Author contributions include the following: E.F. and NT.N.G., concept development as well as the following listed contributions. R.T., A.A., M.S., E.S., and S.C., substantial involvement in the development of the draft manuscript, contributed important intellectual content, data interpretation and development of figures, critical revisions, and discussions around important intellectual content. Final approval of the planned version for publication. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work for accuracy and are committed to the integrity of the final product.

Conflict of interest statement. N.T.N.G. serves on the advisory board for Novocure. All remaining authors have nothing to report.

References

- 1. He F, Deng Y, Li W. Coronavirus disease 2019: what we know? J Med Virol. 2016;92(7):719–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yuki K, Fujiogi M, Koutsogiannaki S. COVID-19 pathophysiology: a review. Clin Immunol. 2020;215:108427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020;109:102433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Avula A, Nalleballe K, Narula N, et al. COVID-19 presenting as stroke. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:115–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Divani AA, Andalib S, Di Napoli M, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 and stroke: clinical manifestations and pathophysiological insights. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29(8):104941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Information for Pediatric Healthcare Providers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 29, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/pediatric-hcp.html. Previous version viewable at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/90713. Accessed June 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu Y, Gayle AA, Wilder-Smith A, Rocklöv J.. The reproductive number of COVID-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus. J Travel Med. 2020;27(2):taaa021. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sanche S, Lin YT, Xu C, et al. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):1470–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Waller M, Stotler C. Telemedicine: a primer. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2018;18(10):54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Doarn CR, Latifi R, Poropatich RK, et al. Development and validation of telemedicine for disaster response: the North Atlantic Treaty Organization multinational system. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24(9):657–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hess DC, Audebert HJ. The history and future of telestroke. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(6):340–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Varma N, Marrouche NF, Aguinaga L, et al. HRS/EHRA/APHRS/LAHRS/ACC/AHA worldwide practice update for telehealth and arrhythmia monitoring during and after a pandemic. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17(9):E255–E268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fava GA. The decline of pluralism in medicine: dissent is welcome. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smith WR, Atala AJ, Terlecki RP, et al. Implementation guide for rapid integration of an outpatient telemedicine program during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231(2):216–222.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hatcher-Martin JM, Adams JL, Anderson ER, et al. Telemedicine in neurology: Telemedicine Work Group of the American Academy of Neurology update. Neurology. 2020;94(1):30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuroda N. Epilepsy and COVID-19: associations and important considerations. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;108:107122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sethi NK. EEG during the COVID-19 pandemic: what remains the same and what is different. Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;131(7):1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guidon AC, Amato AA. COVID-19 and neuromuscular disorders. Neurology. 2020;94(22):959–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yeoh CB, Lee KJ, Rieth EF, et al. COVID-19 in the cancer patient. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(1):16–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mohile NA, Blakeley JO, Gatson NTN, et al. Urgent considerations for the neuro-oncologic treatment of patients with gliomas during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22(7):912–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gosain R, Abdou Y, Singh A, et al. COVID-19 and cancer: a comprehensive review. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020;22(5):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vrdoljak E, Sullivan R, Lawler M. Cancer and coronavirus disease 2019; how do we manage cancer optimally through a public health crisis? Eur J Cancer. 2020;132:98–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Desai A, Warner J, Kuderer N, et al. Crowdsourcing a crisis response for COVID-19 in oncology. Nat Cancer. 2020;1:473–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Luz PLD. Telemedicine and the doctor/patient relationship. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019;113(1):100–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Singh C, Leder D. Touch in the consultation. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(596):147–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stewart M. Reflections on the doctor-patient relationship: from evidence and experience. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(519):793–801. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smith AC, Thomas E, Snoswell CL, et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Telemed Telecare. 2020;26(5):309–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Patel UK, Malik P, DeMasi M, et al. Multidisciplinary approach and outcomes of tele-neurology: a review. Cureus. 2019;11(4):e4410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wechsler LR, Tsao JW, Levine SR, et al. ; American Academy of Neurology Telemedicine Work Group . Teleneurology applications: report of the Telemedicine Work Group of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;80(7):670–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen PM, Hemmen TM. Evolving healthcare delivery in neurology during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Front Neurol. 2020;11:578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mack H. Enterprise video conferencing company Zoom teams up with Epic to launch configurable telehealth platform. MobiHealthNews. April 20, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cahaba Media Group. InTouch launches telehealth platform. HomeCare. April 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Impact of Opening and Closing Decisions by State. 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/state-timeline/. Accessed August 15, 2020.

- 35. Turner M, Fielding S, Ong Y, et al. A cancer geography paradox? Poorer cancer outcomes with longer travelling times to healthcare facilities despite prompter diagnosis and treatment: a data-linkage study. Br J Cancer. 2017;117(3):439–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]