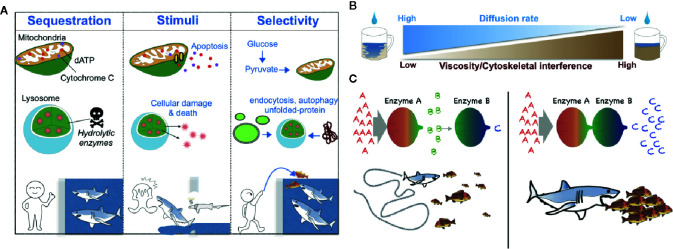

Figure 1.

Schematic models of the biological roles of compartmentalization, viscosity, and local protein concentrations. (A) Metabolic compartmentalization by membrane-bound organelles confines metabolites to organelles to increase reaction efficiency and protect cellular contents—analogous to potential prey that may be protected from sharks by confining the predators to a shark tank (left). Release of organellar contents into the cytoplasm can elicit changes in cell fate (e.g., induction of an apoptotic program by cytochrome C and dATP or cellular damage mediated by lysosomal enzymes)—analogous to sharks that can either attack prey or themselves die when there is a breach in a shark tank (middle). Generally, the transportation of molecules into membrane-bound organelles is highly selective and regulated—analogous to sharks that may be fed without opening oneself up to the possibility of bodily harm by introducing prey into a shark tank from a distance (right). (B) A schematic diagram of the negative correlation between the fluid viscosity of a medium and the diffusion rate of metabolites within it. (C). A schematic diagram of the effect of the local concentration or relative proximity of enzymes belonging to the same metabolic pathway. When Enzymes A and B are spatially separated, Enzyme B can receive only small amounts of its substrate b, which is generated by the distant Enzyme A. Thus, Enzyme B produces only small amounts of its enzymatic product c—analogous to a shark that can catch only a relatively small number of fish when the fish are sparse (left). However, when Enzymes A and B are in close proximity, Enzyme B can receive much more of its substrate b and thus produce much more of its product c—analogous to a shark that can capture more fish when the fish are schooling (right).