Figure 1.

Signaling Heterogeneity along the D-V Axis of the Ao

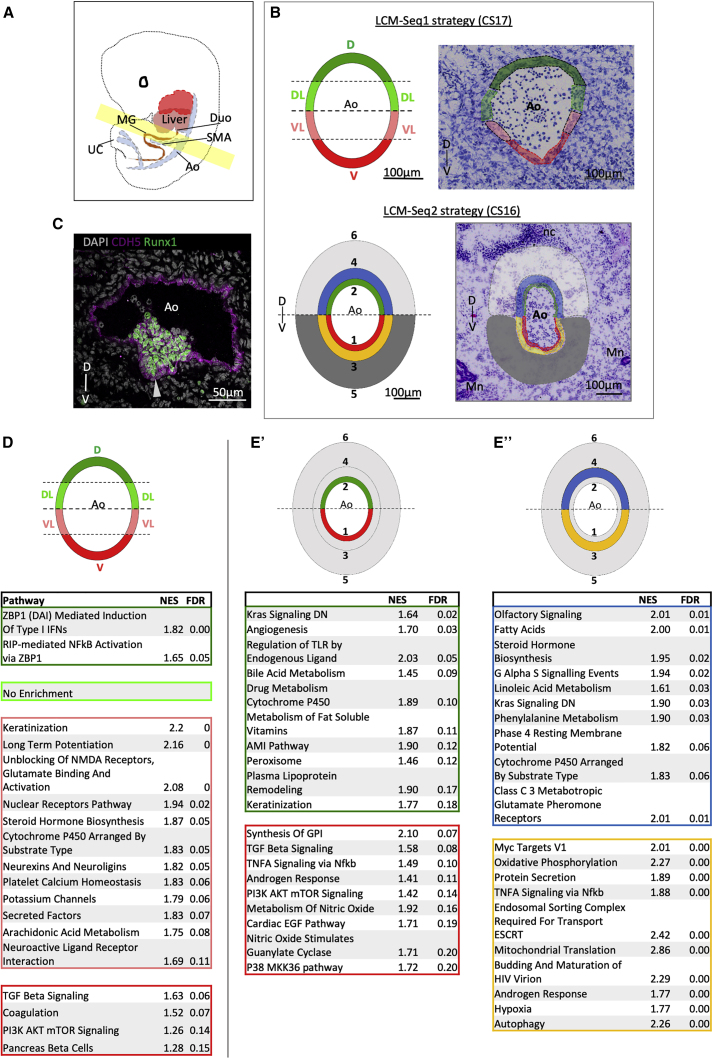

(A) Schematic of a CS16–CS17 embryo. The region highlighted in yellow is taken for LCM-seq; anatomical landmarks of rostral and caudal limits are shown in Figure S1. Ao, dorsal aorta; Duo, duodenum; SMA, superior mesenteric artery; MG, midgut loop; UC, umbilical cord.

(B) Strategy of LCM-mediated subdissection (left) superimposed onto an example Ao transverse section (right) for LCM-seq1 (top) and LCM-seq2 (bottom). V, ventral; VL, ventrolateral; DL, dorsal-lateral; D, dorsal; 1, V_Inner; 2, D_Inner; 3, V_Mid; 4, D_Mid; 5, V_Outer; 6, D_Outer; Mn, mesonephros; nc, notochord.

(C) Sister section stained for CDH5 and Runx1 using antibody staining. The arrowhead indicates an IAHC adhering to the V endothelium.

(B and C) The D-V axis is indicated.

(D and E) Top pathways by false discovery rate (FDR) for LCM-seq domains highlighted in the schematic. The color of the table corresponds with the subdomain indicated in the schematic above. FDR < 0.25.

(D) LCM-seq1: D, DL, VL, and V (each versus the remaining 3 domains).

(E) LCM-seq2: V_Inner (red) versus D_Inner (green) (E’) and V_Mid (yellow) versus D_Mid (blue) (E’’).

Numbers of significant differentially expressed genes for each contrast are shown in Figure S1B.