Abstract

The current epidemic of obesity and its associated metabolic syndromes imposes unprecedented challenges to our society. Despite intensive research focus on obesity pathogenesis, an effective therapeutic strategy to treat and cure obesity is still lacking. The obesity development is due to a disturbed homeostatic control of feeding and energy expenditure, both of which are controlled by an intricate neural network in the brain. Given the inherent complexity of brain networks in controlling feeding and energy expenditure, the understanding of brain-based pathophysiology for obesity development is limited. One key limiting factor in dissecting neural pathways for feeding and energy expenditure is unavailability of techniques that can be used to effectively reduce the complexity of the brain network to a tractable paradigm, based on which a strong hypothesis can be tested. Excitingly, emerging techniques have been involved to be able to link specific groups of neurons and neural pathways to behaviors (i.e., feeding and energy expenditure). In this chapter, novel techniques especially those based on animal models and viral vector approaches will be discussed. We hope that this chapter will provide readers with a basis that can help to understand the literatures using these techniques and with a guide to apply these exciting techniques to investigate brain mechanisms underlying feeding and energy expenditure.

Keywords: Inducible and conditional gene targeting, Genome editing, Optogenetics, Chemogenetics, Neural circuit mapping, Energy balance, Body weight

12.1. Introduction

The current epidemic of obesity and its associated metabolic syndromes imposes unprecedented challenges to our society. Despite intensive research focus on obesity pathogenesis, an effective therapeutic strategy to treat and cure obesity is still lacking. The obesity development is due to a disturbed homeostatic control of feeding and energy expenditure, both of which are controlled by an intricate neural network in the brain. Given the inherent complexity of brain networks in controlling feeding and energy expenditure, the understanding of brain-based pathophysiology for obesity development is limited. One key limiting factor in dissecting neural pathways for feeding and energy expenditure is unavailability of techniques that can be used to effectively reduce the complexity of the brain network to a tractable paradigm, based on which a strong hypothesis can be tested. Excitingly, emerging techniques have been involved to be able to link specific groups of neurons and neural pathways to behaviors (i.e., feeding and energy expenditure). In this chapter, novel techniques especially those based on animal models and viral vector approaches will be discussed. We hope that this chapter will provide readers with a basis that can help to understand the literatures using these techniques and with a guide to apply these exciting techniques to investigate brain mechanisms underlying feeding and energy expenditure.

12.2. Conditional and Inducible Gene Targeting Through Cre/loxP Recombination

The complete gene knockout (KO) in mice through homologous recombination permits investigation of the biological roles of specific genes in vivo [1, 2]. However, this technology becomes obsolete as a result of some obvious caveats, including embryonic lethality, no desirable phenotype, and lack of specificity for genes simultaneously expressed in multiple cell or tissue types [3, 4]. To overcome these obstacles, Cre recombinase isolated from bacteriophage P1 has emerged as a popular tool to achieve site-specific gene targeting in mouse models [5–8]. The Cre recombinase catalyzes excision of a “floxed” DNA fragment, a region which is flanked by two 34-bp loxP elements, placed in direct orientation [9]. The 34-bp long sequence of loxP, which is absent in the endogenous mouse genome, is made of two 13-bp inverted repeats as the Cre-binding sites with an 8-bp spacer region in the middle [10–13]. To achieve tissue-specific knockout of gene of interest (GOI) in a mouse model, the following steps are required for successful implementation of this Cre/loxP binary system [5] (Fig. 12.1):

The floxed mouse can be created by homologous recombination (HR) in ES cells, in which one or multiple essential exons of the GOI are flanked by two loxP sites located in intronic regions. The loxP sites should not disturb gene transcription so that the floxed mouse carrying two floxed alleles displays a wild-type phenotype.

To generate a Cre-driver mouse, the coding sequence of Cre recombinase is introduced by either knock-in or BAC transgenic approach to ensure ectopic expression of Cre recombinase under the control of a carefully chosen promoter. The promoter practically determines the cell lineage or tissue specificity of the Cre expression profile. The pattern of Cre-mediated gene targeting can be validated by breeding the Cre mouse with a “reporter” mouse line in which a reporter allele (such as beta-galactosidase and green fluorescent protein or GFP) is driven by a strong and ubiquitous promoter but is interrupted by a transcription STOP cassette flanked by loxP sites [14–16]. A reporter expression pattern would indicate whether the Cre driver is expressed in the desired cell types.

Breeding the floxed mouse with the Cre-driver mouse leads to irreversible excision of the floxed exons in cells expressing Cre recombinase, thereby rendering gene inactivation specifically in Cre-expressing tissues or cells [17–19]. To perform gain-of-function genetic analysis, a loxP-STOP-loxP cassette is introduced upstream of the first exon of the targeted gene, leading to disrupted gene expression, i.e., KO. As the next step, breeding a Cre mouse with this floxed KO mouse removes the STOP cassette, and normal gene expression can be restored exclusively in the Cre-expressing cell types [20–23].

Fig. 12.1.

Schematic representation of the conventional Cre/loxP-mediated conditional gene knockout

Over the past decades, the Cre/loxP strategy has been evolved as the most popular binary recombination system, allowing versatile and efficient control of gene expression. One successful case in application of Cre/loxP binary expression system in energy metabolism research is the use of a Pro-opiomelanocortin (Pomc)-Cre line for targeting metabolism-relevant genes in a defined subpopulation of hypothalamus neurons [24, 25]. This strategy unraveled the mechanistic insights of an array of hormonal signaling systems, such as leptin and ghrelin, in mediation of energy homeostasis through differential action upon POMC neurons [26]. Furthermore, characterization of mice carrying Pomc-Cre and floxed genes that governs critical cellular processes including endoplasmic reticulum stress, mitochondrial uncoupling proteins, and autophagy system demonstrated their unique yet critical roles in control of body weight and metabolism [27–31].

The classical Cre/loxP binary expression, though achieved great success in genetic manipulation, lacks temporal control of gene expression. In the strategy by breeding Cre mice with floxed mice, genetic manipulation occurs as soon as the promoter-driven Cre expression is turned on during the early developmental stage. The early Cre expression, either transiently or persistently, may trigger developmental compensation as commonly displayed by global KO approach, thus masking the desired phenotypes. Furthermore, because the expression pattern of some promoters in early stage is markedly different from that of adult stage, early Cre expression may lead to widespread recombination in many undesired places. This caveat potentially makes the functional data difficult to interpret. To achieve a better understanding of physiological roles of genes, the onset of Cre-mediated recombination is desirable to be controlled independently from the endogenous regulatory elements [8, 9].

As an alternative yet efficient approach, Cre recombinase can be introduced to floxed mouse through viral transduction. Cre-expressing adenovirus (Ad) or adeno-associated virus (AAV) can be injected through various routes to target genes within individual peripheral organs or a restricted brain area [32–34]. Used in adult animals, this strategy circumvents the developmental compensation and often results in rapid and efficient recombination within a restricted surrounding area at the injection site [21–23, 35–37]. Despite the lack of inheritance, some studies indicated that phenotypes from AAV-mediated genetic knockout were maintained for up to 6 months [38].

The tamoxifen-based CreER system was developed in the late 1990s and has been emerged as a popular tool to achieve inducible control of gene expression [39] (Fig. 12.2). This technique takes advantage of the nuclear localization capacity of a ligand-binding domain of human estrogen receptors (ER) fused with the coding sequence of Cre recombinase. This strategy ensures the restriction of HSP90-bound CreER within the cytoplasm unless exposed to an estrogen receptor antagonist, tamoxifen or 4-hydroxytamoxifen [6]. The CreER fusion protein translocates into the nucleus to cause cell-specific recombination once transgenic mice are treated with tamoxifen at a desired development or post-development stage [40]. To date, a large repertoire of conditional mutant mice carrying floxed alleles, floxed reporters, or Cre/CreER drivers have been generated by numerous mouse genetic labs and several large-scale collaborative initiatives, including the GENSAT Project (Rockefeller University), AIBS Transgenic Mouse Project (Allen Institute for Brain Science), RIKEN (Japan), MMRRC (NIH), and JAX [5, 14, 41–43]. Majority of these mouse strains are maintained as either live or cryo-stocks and readily to be distributed to researchers. The ever-increasing amount of Cre/loxP mouse inventory will undoubtedly facilitate a more complete understanding of the biological processes underlying energy homeostasis.

Fig. 12.2.

Schematic representation of the inducible CreER/loxP-mediated gene knockout

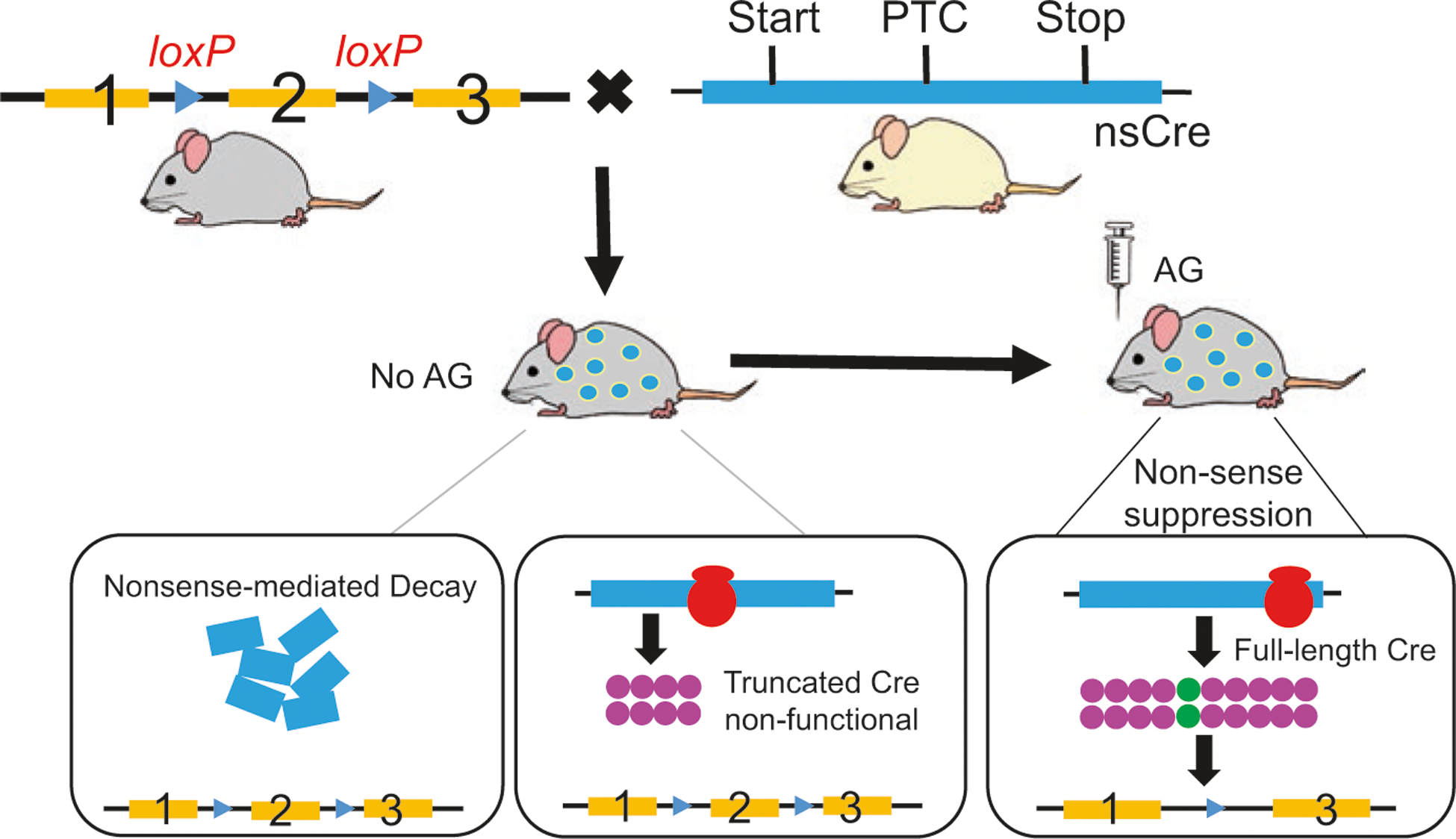

Emerging evidences suggest that the CreER system possesses some non-negligible caveats in addressing fundamental biological issues, such as weak recombination, silencing effects, as well as CreER- and tamoxifen-mediated metabolic side effects and cytotoxicity in particular organs [44–50]. To overcome these limitations, a new nsCre system by introducing a premature termination codon (PTC) into the coding sequence of Cre gene (nsCre) was designed (Fig. 12.3) [51]. It is conceivable that the mRNA transcribed from nsCre transgene cannot be fully translated into functional Cre recombinase unless suppressing the PTC by aminoglycoside (AG)-based compounds [52, 53]. Results from in vitro and in vivo proof-of-concept paradigms demonstrated that administering AG compounds into a pre-defined brain region of adult transgenic animals within any desired time window achieved rapid and specific control of gene targeting [51]. This new inducible nsCre system has been successfully applied in the genetic disruption of GABA biosynthesis in AgRP neurons 4 days after administration of AG [51]. Rapid and total deletion of GABA signaling from AgRP neurons in young adult animals abolished feeding response, increased energy expenditure, exacerbated glucose tolerance, and ultimately resulted in severe starvation manifesting the AgRP neuron ablation model [51]. Unlike lipid-soluble tamoxifen, applicable AG derivatives cannot penetrate the blood-brain barrier or diffuse far from the site of injection [54]. Thus, the new nsCre system is particularly useful to distinguish between central and peripheral contributions when endogenous expression profile of the gene of interest exists in both the brain and periphery. Targeting specific genes with a widely distributed pattern within the brain may also be easily achieved. Together, this nonsense suppression-based genetic system provides an ideal strategy in achieving conclusive results for many complicated, compensatory mechanism-protected, physiological, and neurological processes.

Fig. 12.3.

Schematic representation of the inducible nsCre/loxP-mediated gene knockout.

The nonsense mutation that generates a premature termination codon (PTC) is inserted into the coding sequence of Cre recombinase (nsCre). Transgenic mice carrying the nsCre and homozygous floxed gene of interests are made. When in the absence of aminoglycoside (AG), PTC-containing mRNA is predominantly degraded through the process of nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), while the remainder is translated to truncated nonfunctional Cre. When AG (e.g., Geneticin) is administered into adult animals, AG suppresses the decay of the PTC-containing premRNA at the site of transcription, represses the proofreading mechanism of the ribosomal complex inserting a random amino acid at the PTC, and finally generates full-length, functional, Cre proteins. This whole process is termed nonsense suppression. The functional Cre then catalyzes the genetic recombination of the floxed gene. Once AG is metabolized by the Cre-expressing cells or tissues, the nonsense suppression is rapidly reinstated to stop further production of functional Cre

12.3. Dissection of Neural Circuit by Recombinant Rabies Virus

Deciphering the neural mechanisms in control of feeding behavior and body weight requires knowledge of the synaptic connectivity of relevant neural circuits as well as the relationship between each defined neural circuit and physiological function. Rabies virus, a negative-sense single-stranded RNA [(−)ssRNA], has outstanding capacity as a retrograde tracer of neuronal populations that are synaptically connected [55–58]. There are several advantages of rabies virus over another family of retrograde viral tracers, i.e., α-herpes viruses which include herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and pseudorabies virus (PRV):

Rabies virus displays a significantly reduced cytotoxicity.

Rabies virus has the capacity to infect the brain of primates.

Herpes viruses typically have a lysis phase that often leads to the release of viral particles from host cells and infect nearby cells through non-synaptic manner.

Rabies virus can be easily genetically engineered due to the fact that it has a genome of only ~12 kb that harbors 5 coding genes, while herpes viruses have genomes of ~150 kb that code for more than 70 genes [55].

Altogether, these features make rabies virus a useful retrograde tracer for studying the functional connectivity of neural circuit [56, 59]. However, like other trans-synaptic viruses, wild-type rabies virus is a polysynaptic tracer that leads to potential ambiguity in determination of how many synaptic steps have been crossed at any given time [55]. This caveat poses a challenge to dissection of a precise pattern of synaptic connectivity, considering the vast cohort of neuronal types within the brain, the large number of synapses existing on each neuron, and the high degree of connectivity in intact neural circuits. Furthermore, it is not possible to apply this method for combined circuit tracing and gene manipulation of the first-order neurons, since high-order neurons will also be affected (see more details below).

In recent years, a glycoprotein-deleted (ΔG) rabies virus has been developed and recognized as a robust toolbox for monosynaptic circuit analysis [60–62] (Fig. 12.4). The envelope glycoprotein (RG) is essential not only for the assembly of infectious viral particles during the natural cycle of rabies virus but also for the trans-synaptic crossing of the virus [63, 64]. Genetic deletion of RG gene or swap-out with a GFP reporter from the SAD-B19 rabies genome leads to the restriction of viral infection to the first-order neurons at the injection site [61]. To restore the trans-synaptic capacity, RG-deleted rabies virus is pseudotyped with an avian virus envelope protein named EnvA; such virus is therefore called EnvA-SADΔG-GFP [61]. Once the virus is injected into the brain of wild-type mice, it cannot infect any neurons because the mammalian neurons lack the cognate receptor for EnvA, called TVA. However, pretreatment of AAV vector carrying the coding gene for TVA to the same brain region warrants efficient infection of TVA-expressing neurons by EnvA-SADΔG-GFP rabies virus [55].

Fig. 12.4.

Schematic representation of pseudotyped rabies virus for retrograde monosynaptic tracing

Since RG is required for packaging new viral particles and trans-synaptic propagation, and SADΔG-GFP does not carry the coding sequence for RG, RG should be introduced to the same group of neurons typically through AAV-mediated viral transduction [65]. If TVA but not RG is expressed, infection with EnvA-SADΔG-GFP rabies virus (with GFP marker) would be restricted to TVA-positive neurons and cannot spread over to the presynaptic neurons. If neurons express both TVA and RG, TVA would allow initial infection of rabies virus, while RG in those cells allows trans-synaptic propagation and GFP labeling of the second-order neurons with direct synaptic projection to these cells. Importantly, continued propagation beyond the second-order neurons cannot occur, because these presynaptic neurons do not express RG and there is no RG-coding sequence in the rabies genome [56]. Therefore, this system warrants monosynaptic spread of rabies virus, which eliminates the ambiguity about the number of synapses that have been crossed. More interestingly, the pseudotyped rabies tracing strategy can be further adapted to Cre-driver mouse lines to achieve cell-/tissue-specific control of TVA and RG expression [66].

One of the great advantages of ΔG rabies virus-mediated monosynaptic tracing over other existing approaches (such as electron microscopy [EM] and paired electrophysiological recording) is the capacity to identify long-range, direction-specific, synaptic connectivity [60, 67, 68]. A few recent studies successfully applied this new technology to interrogate hypothalamic circuits in control of appetitive and cognitive behaviors [67, 68]. In order to decipher the excitatory inputs to AgRP neurons that control caloric-deficiency-induced activation, the Cre-dependent AAV-FLEX-RG and AAV-FLEX-TVA-mCherry viruses (Fig. 12.4) were co-injected into the arcuate nucleus (ARC) where AgRP neurons are located [67]. As the next step, EnvA-SADΔG-GFP rabies virus was injected to the same region in the ARC to allow rabies infection of AgRP neurons that express TVA-mCherry and RG. The rabies virus was thus supposed to retrograde from AgRP neurons to presynaptic cells which can be visualized by the GFP reporter carried from trans-synaptically propagated rabies virus. Using this technique, these authors made a surprising discovery that major excitatory inputs to the AgRP emanate from two discrete neuronal populations in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN). Application of a similar tracing strategy leads to identification of a novel connection between oxytocin-expressing neurons within the PVN and neurons in the central amygdala, a pathway which is critical for the control of fear response [68]. In this study, synaptic connections were further supported by several lines of results derived from optogenetic manipulation and EM-based histological data [68]. Nevertheless, rabies virus tracing results, for the first time, established the monosynaptic property of this critical neural circuit.

Beyond the tremendous success in neural tracing analysis, a variety of ΔG rabies virus variants have recently been developed by amalgamating with some newly developed genetic toolboxes. These variants include ΔG rabies vectors carrying trans-acting factors such as Cre and FLP recombinase, genetically encoded Ca2+ sensors, and molecules for activation or silencing of neural circuits such as channelrhodopsin-2 and allatostatin receptors [69, 70]. These emerging techniques, when combined with Cre/FLP-driver mice or conditional mouse models, allow precise genetic and functional analysis in defined neuronal circuits.

12.4. Optogenetics

Optogenetics, as reflected by its name, uses a combination of light and genetic methods to enable precise perturbation of neurocircuits in living animals. This technique utilizes light-activated microbial opsins, which can be genetically expressed in neurons to achieve rapid control of neuron activity by light [71, 72]. The principle underlying light-mediated activation is photoisomerization of the chromophore retinal. Similar to light-sensing in retina of vision sensing, photo isomerizes the alltrans retinal, which leads to a series of conformational changes of opsins [73]. These conformational changes result in ion transports across the membrane, which, in stark contrast to light sensing in the retina, results in changes in signal transduction instead of ion transport [73]. This striking difference makes it possible to effectively apply microbial opsins in mammalian systems without interfering endogenous signaling pathways by light. Interestingly, the endogenous retinal in mammalian neurons can tolerate well with foreign microbial opsins, and no additional retinal is required for microbial opsin to mediate light-induced ion transport in mammalian neurons. In turn, microbial opsins can also tolerate well with fusion with other proteins such as green and red fluorescent proteins (GFP and RFP) without affecting their ion transport ability or light sensitivity, which makes it easy to track transgenic and functional expression of microbial opsins in mammalian neurons. In addition, low intensity of light illumination (below 10 mW) is required to activate these opsins, which greatly limits potential damage to tissues directly by light illumination. Due to its capability of rapid control of neuron activity with a high level of fidelity and precision, noninvasive control by light, and reversibility, the optogenetics has gained rapid popularity. Since the first application of microbial opsins in mammalian neurons, a variety of microbial opsins as well as various mutations and hybrids have been generated with an aim to achieve better performance. The distinct features of these opsins have been intensively reviewed elsewhere [73–77]. Discussions on application of optogenetics in the investigation of a variety of brain disorders, including mood disorders, anxiety, addiction, Parkinson’s diseases, etc., have also been reviewed elsewhere [78–82]. This section will briefly introduce the most utilized opsins including channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2), halorhodopsin (Halo), and archaerhodopsin (Arch), which have been used for neuronal excitation (ChR2) or inhibition (Halo and Arch) as well as their application in understanding brain control of feeding and energy expenditure (Fig. 12.5).

Fig. 12.5.

Schematic representation of channelrhodopsins, halorhodopsins, and archaerhodopsins

ChR2 was first identified to be a light-gated cation channel in 2002 [83–85] and was demonstrated to conduct nonselective cation influx in neurons and therefore reliably control neuron activity in 2005 [72, 86, 87]. ChR2 can be expressed stably and safely in mammalian neurons, in which blue light illumination can reliably induce sustained activation with a rapid kinetics (milliseconds). The firing of neurons can be induced in a scalable way by delivery of a large range of frequency and duration of light stimulation [86]. ChR2, upon receiving light illumination, will undergo conformational changes and open its channel for passive conductance of cations, rendering it as an efficient cation channel [73, 88]. Importantly, ChR2 expression, without light illumination, causes no discernable effects on neurons [86]. Thus, ChR2 is an ideal candidate as a tool to activate neurons and investigate their physiological effects. To overcome some limitation with native ChR2, mutations have been made on ChR2 with an aim to be able to use light to better control neuron activity with precision. Toward this, many mutations have been generated. ChR2 with H134R mutation (ChR2/H134R) exhibits reduced desensitization and increased light sensitivity [74, 87], which increases photocurrents and is so far the most popular tool in the field of brain control of metabolism.

To complement the application of ChR2 that activates neurons, Halo was explored to silence neurons based on its light-driven chloride pumping activity (Fig. 12.5). When Halo from Natronomonas pharaonis (NpHR) was expressed in neurons, long-duration light pulses induce long-term steady inhibition, and short-duration light pulses reliably inhibit single action potentials induced by current injection across a broad range of frequencies [71, 89]. Similar to ChR2, light activation of NpHR induces Cl−-mediated currents with fast kinetics within milliseconds [71, 89]. So NpHR can effectively serve as an optical inhibitor of neuronal activity. A major difference between NpHR and GABAA receptors, a chloride channel, is that the former is a pump and will only cause membrane potential changes, but not input resistance, while the latter will cause a reduction in input resistance. Excitingly, due to differential action spectrums of ChR2 and NpHR by light, it is possible to use distinct wavelengths of lights to activate and silence the same neurons [71, 89], allowing a simultaneous bidirectional control of neuron activity with light. Thus, use of combination of ChR2 and NpHR will be able to test the sufficiency and requirement for brain neurons in physiology simultaneously. To overcome poor membrane targeting, an advanced version of NpHR has been generated (eNpHR3.0), which, when expressed in mammalian neurons, exhibits improved membrane targeting and photocurrents [90]. However, a brief episode of eNpHR3.0 activation tends to increase the probability of spiking in response to a volley of presynaptic action potentials [91], presumably due to its depletion of normal Cl− gradient of neurons. This alteration of baseline neuron activity might confound and therefore limit the use of this opsin in mammalian neurons.

Archaerhodopsin (Arch) is a green-yellow light-driven outward proton pump and therefore can hyperpolarize neurons (Fig. 12.5). When expressed in mammalian neurons, Arch can also produce hyperpolarizing current with millisecond temporal precision [92]. Compared to eNpHR3.0, the advanced version of Arch, eArchT3.0, showed better membrane targeting, higher sensitivity to light, and higher photocurrents [90, 93]. Importantly, it appears that the outward proton pump activity is not associated with any alterations in intracellular pH due to the intrinsic compensatory mechanism [91]. This feature is in contrast to eNpHR3.0, which, as discussed above, is able to cause changes in Cl− gradient. Thus, eArchT3.0 appears to be a better choice to silence mammalian neurons.

A combination of optogenetics and Cre-loxP technology provides an unprecedented specificity in manipulating neuron activity. The Cre-loxP technology provides a specificity in the expression of opsins, and the optogenetic approach provides a specific regulation by light in a rapid inducible and reversible fashion. Currently, a variety of viral vectors are available with Cre-dependent expression of ChR2, eNpHR3.0, eArchT3.0, or other opsins. The Cre-dependent expression is achieved by an elegant design of double-floxed inverted open reading frame (DIO) or flip-excision (FLEX) strategy, in which the inverted opsin reading frame is flanked by two sets of floxed sequences (Fig. 12.6). Cre-mediated inversion of DIO/FLEX will allow functional expression of opsins. A typical example of using a combination of optogenetics and Cre-loxP technology is ChR2-assisted circuit mapping (CRACM), by which monosynaptic connectivity can be identified if light-stimulated presynaptic neurons induce a time-locked postsynaptic current within a few milliseconds (Fig. 12.7). Due to irregular distribution and diffusive projections of hypothalamic neurons, monosynaptic connectivity between these neurons is particularly difficult to ascertain. As discussed below, CRACM has been frequently used to determine monosynaptic connectivity between hypothalamic neurons.

Fig. 12.6.

Schematic diagram showing DIO/FLEX strategy in which the expression of ChR2-EYFP in the viral vector is dependent on Cre-mediated flip of the inverted ChR2-EYFP coding sequence

Fig. 12.7.

A representative example showing CRACM. (a) Diagram showing GABAergic projections from lateral hypothalamic (LH) to PVH neurons. (b) Picture showing an actual recording setup with a brain section containing PVH neurons, a recording pipette, and an optic fiber. (c) Actual current traces showing time-locked (less than 5 ms) inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) in response to each blue light stimulation

The optogenetics approach has greatly enhanced our understanding on brain neural pathways controlling feeding and metabolism. It is well established that hypothalamic neurons expressing agouti-related protein (AgRP neurons) are important for feeding [94, 95]. However, it was unknown how and whether these neurons act alone or in concert with other neurons to promote feeding. With blue light activation of AgRP neurons expressing ChR2 in live animals, the animals exhibit robust feeding, and the feeding behavior correlates with light activation [96], demonstrating that AgRP neurons are sufficient to orchestrate feeding without training or co-activation of any other neurons. Furthermore, light activation of AgRP neurons induces monosynaptic inhibitory currents in nearby POMC neurons as well as those in the paraventricular hypothalamus (PVH), proving a direct GABAergic projection from AgRP neurons to POMC and PVH neurons [97]. In contrast, light activation of POMC neurons fails to induce any monosynaptic responses in AgRP neurons [97], demonstrating a unidirectional interaction between AgRP and POMC neurons. It is perceivable that clear delineation of neurocircuits and their roles in feeding wouldn’t have been established without the application of optogenetics. Similarly, light stimulation of ChR2-expressing GABAergic neurons in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) stimulates feeding, while that of glutamatergic neurons in the LHA inhibits feeding [98], identifying a previously unknown role for these neurons in potently regulating feeding behavior. Notably, light inhibition of eArchT3.0-expressing GABAergic neurons in the BNST inhibits feeding in food-deprived animals [98], demonstrating an importance of these neurons in feeding inhibition. This is one of first examples of using eArchT3.0-mediated neuron inhibition for feeding regulation.

Efficient expression of ChR2 in remote fibers allows specific activation of these fibers by light in vivo, which can be used to examine specific physiological roles of distinct remote sites that mediate the function of ChR2-expressing neurons. For example, specific activation of ChR2-expressing AgRP fibers in the PVH, BNST, lateral hypothalamic area (LHA), paraventricular thalamus (PVT), or central amygdalar nucleus (CEA) all produces robust feeding behavior [99], suggesting parallel and redundant projections from AgRP neurons to these discrete sites in feeding promotion. Similarly, light stimulation of ChR2-expressing local fibers in the CEA of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) neurons in the parabrachial nucleus (PBN) suppresses feeding [100], demonstrating a role for PBN CGRP projections in the CEA in feeding suppression. In addition, local stimulation of GABAergic local fibers in the PVH coming from the LHA increases feeding [101], suggesting a role for PVH in mediating the feeding behavior by stimulating LHA GABAergic neurons. Furthermore, local stimulation of GABAergic fibers in the VTA coming from LHA GABAergic neurons also stimulates feeding [102]. Thus, LHA GABAergic neurons promote feeding also through parallel and redundant pathways, and PVH and VTA are at least part of downstream brain sites mediating the feeding behavior.

As discussed above, single use of excitatory ChR2 and inhibitory eArchT3.0 has been used to study neuron function in feeding regulation. However, to delineate neural pathways, it is imperative to determine whether the putative downstream neurons are responsible for mediating the feeding effect. To achieve this goal, dual stimulations with light to control the activities of both upstream and downstream neurons are required. Notably, due to a difference in action spectrum, different rhodopsins can be concurrently activated by respective lights at a distinct wavelength without affecting each other [71, 89, 103]. This multimodal independent control of neuron activity allows interrogation of downstream neurons that mediate behaviors. As illustrated as an example of occlusion experiments in Fig. 12.8, excitation of neuron A releases glutamate onto neuron B and inhibits feeding. To determine whether excitation of neuron B is required for the feeding inhibition, one could express ChR2 in neuron A and eArchT3.0 in neuron B, allowing simultaneous activation of local GABAergic fibers originated near neuron A and inhibition of neuron B with illumination of both blue and yellow lights. If inhibition of neuron B by yellow light reduces the feeding inhibitory effect elicited by blue light activation of neuron A, then neuron B is at least one of downstream mediators of neuron A in feeding inhibition. This method has nicely been employed in establishing that inhibition of PVH neurons is required to mediate AgRP feeding promotion [97] as well as that excitation of parabrachial neurons is required to mediate PVH MC4R-expressing neurons in feeding inhibition [104].

Fig. 12.8.

Schematic diagram showing an occlusion experimental model

With the development of more advanced versions of opsin and new lines of Cre animals with more specific and restricted expression in the brain, the application of optogenetics approach to understand brain mechanism in feeding/energy balance regulation will become more versatile and powerful. The noninvasive light-mediated control of neuron activity with millisecond kinetics and reversibility offers an unprecedented precision to correlate neuron activity with feeding behavior. However, despite the current popularity of using optogenetics, cautions must be exercised in applying this technique, and a few drawbacks have been noticed with this technique [105]. Most studies using optogenetics on freely living animals require implantation of optic fibers for light delivery, which will inevitably cause damage to brain tissues and will potentially confound the ongoing studies. Associated with light illumination is light-induced heat production, which itself may alter neuron activity. In addition, ChR2-mediated excitation can sometimes induce depolarization block [106], and inhibitory opsins can also induce hyperpolarization-induced activation of cation channels and therefore rebound action potential firings [107, 108], both of which may confound interpretation of experimental results. Another major drawback is that optogenetic control of neuron activity is purely artificial and the magnitude of excitation (ChR2) or inhibition (eArchT3.0 or eNpHR3.0) may never be experienced in any physiological circumstances and, therefore, behavioral phenotypes (i.e., feeding) may be artificial. Thus, additional physiological experiments are required to extrapolate the significance of behavior phenotypes from optogenetic studies. Finally, artificial manipulations of neuron activity with optogenetics are conducted without real-time monitoring of neuron activity. Real-time monitoring of neuron activity is key to establish a causal relationship between neuron activity and behavior [109]. For example, light stimulation of ChR2-expressing AgRP neurons causes voracious feeding, and the duration of feeding depends on duration of light stimulation [96], which might indicate that AgRP neuron activation drives feeding behavior. However, recent studies with real-time monitoring AgRP neuron activity in live animals demonstrate that initial feeding requires AgRP neuron activation but continuous feeding is not and, instead, is associated with reduced AgRP neuron activity [110, 111]. These contrasting results suggest a need to exercise caution when using optogenetics to blindly manipulate neuron activity to study behavior.

To address potential issues associated with optogenetics, more efforts have been investigated to improve its performance. Wireless delivery of light has been actively pursued to achieve remote delivery of light for optogenetic control of deep brain neurons [112–114]. New opsins with faster kinetics and better sensitivity to light have been actively sought, for example, a recent study reported a new, natural anion channelrhodopsin, which requires less than one thousandth of the light intensity than required by the most efficient currently available optogenetic rhodopsins [115]. Importantly, a close-loop strategy has been proposed to use with optogenetics to achieve optic control of neuron activity based on real-time monitoring neuron activity and behavior output [109]. These technical and conceptual advances will lead to a more efficient application of optogenetics in the identification of key neurons and neural pathways in the brain that control feeding and energy expenditure.

12.5. Chemogenetics

Chemogenetics, also termed designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADD), involves expression of an artificial receptor, normally a G-protein-coupled receptor, which lacks endogenous ligands but can effectively engage intracellular signaling pathways, normally through G-protein-mediated signaling, by an artificial ligand, which is usually a chemical but with no endogenous activity [116, 117]. Thus, pharmacological application of ligands can achieve remote control of G-protein-coupled signaling pathways. Since ligands activate G-protein-coupled signaling, this approach can virtually be used for all kinds of cells with G-proteins. This approach was initially developed by Dr. Bryan Roth of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Through mutation of human muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, an excitatory DREADD receptor was generated (hM3Dq), which completely loses the binding of acetylcholine, but can be effectively activated by an otherwise pharmacologically inert drug, clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) [118]. Importantly, once activated by CNO, hM3Dq receptors will activate Gq-protein-coupled signaling pathways, leading to an elevation of intracellular Ca2+ and thus activation of neurons [97, 119–121]. With a similar approach, the inhibitory DREADD (hM4Di) receptors, which induce Gi-protein-coupled signaling pathways by activation of CNO, were generated and can be used to achieve remote inhibition of neurons that express this receptor [97, 118, 121, 122]. Recently, Gs-DREADD has also been generated to induce the cAMP pathway once activated by CNO [123, 124]. Given the fact that it utilizes the intracellular pathways and involves in vivo pharmacology, the DREADD approach can be applied to address questions in a more “physiological” sense and has gained rapid popularity in the field of neuron control of feeding and metabolism. Similar to optogenetics, a few animal models [119, 124, 125] and a variety of vectors with Cre-dependent expression of DREADDs have been generated [97, 116, 121]. These vectors can be used in combination with Cre-loxP technology to achieve a high level of controlled specificity in targeted expression and activation. Of note, mice with knock-in of Cre-dependent expression of Gs-, Gi-, or Gq-coupled DREADD receptors have all become available from the Jackson Laboratory, which will greatly expedite the research using DREADD approaches for neuronal control of feeding and other behaviors. The controlled expression, inducibility, and reversibility (degradation of CNO within a few hours) make the DREADD approach powerful to link neuron activity with behavior.

The showcase of the application of both hM3Dq and hM4Di has been demonstrated on AgRP neurons. CNO effectively increases and reduces the excitability of AgRP neurons that express hM3Dq and hM4Di, respectively [121]. Mice with specific expression of hM3Dq in AgRP neurons respond to CNO with voracious feeding and those with hM4Di in the AgRP neurons with reduced feeding [121]. These results illustrate the effectiveness of in vivo pharmacological CNO in controlling AgRP neuron activity. With a combination of DREADD and mouse genetics, differential roles of neurotransmitters, GABA, NPY, and AgRP, have been shown to mediate feeding behavior of AgRP neurons [126]. For POMC neurons, although it is well-established that these neurons suppress feeding, how these neurons located in different brain regions (hindbrain versus hypothalamus) regulate feeding is unknown. With specific hM3Dq expression in different brain regions of POMC neurons, it has been shown that POMC neurons in the hindbrain mediate short-term feeding suppression, whereas those in the hypothalamus mediate long-term feeding suppression [127]. DREADD-mediated activation of leptin receptor neurons in the dorsomedial hypothalamus increases energy expenditure and reduces body weight [128], demonstrating a sufficiency for these neurons in promoting energy expenditure. Notably, DREADD is also able to efficiently activate tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-expressing neurons in rats to regulate feeding behavior [129], suggesting DREADD as a versatile approach in different species.

Of interest, DREADD has recently been explored to probe functions of subcellular regions in neurons. Using an axon-targeting approach, the inhibitory hM4Di is targeted preferentially to remote axon terminals of PVH single-minded 1 (Sim1) neurons. Stereotaxic delivery of CNO to distinct projection sites of Sim1 neurons reveals that isolated inhibition of glutamate release from Sim1 neurons restricted to the periaqueductal gray (PAG) regions is sufficient to promote feeding, nicely demonstrating a role for PAG neurons in mediating PVH Sim1 neurons in feeding regulation [130]. Importantly, DREADD can be used in conjunction with the optogenetics to identify novel neural pathways for feeding and energy metabolism. For example, the CRACM technology has helped identification of a novel excitatory drive from PVH neurons that express thyroid-releasing hormone (TRH neurons) to AgRP neurons [67]. With a combination of excitatory hM3Dq expressed in TRH neurons and inhibitory hM4Di expressed in AgRP neurons, it has been demonstrated that feeding promotion by PVH TRH neurons is mediated by AgRP neurons [67]. These sets of experiments convincingly identified a previously unknown glutamatergic pathway from PVH TRH neurons to AgRP neurons in feeding regulation.

In comparison to optogenetics, the DREADD approach has a much slower kinetics. Long diffusion (minutes) and clearance (hours) time associated with CNO administration renders this approach to lack a precise temporal control of neuron activity, which may potentially confound delineation of complex neuronal circuits for behavior. However, this long duration of action may provide an advantage to studies that require long-duration observations of behaviors such as feeding and energy expenditure. For example, measurements of energy expenditure require a relatively long duration and enclosed chambers, which are not compatible with prevalent optogenetic applications with tethered optical cables. Using DREADD, the function of a group of arcuate GABAergic neurons in promoting energy expenditure has been elegantly demonstrated [131]. Thus, for a given study, it may be more effective to combine optogenetics and DREADDs, as illustrated above in delineation of TRH neuron to AgRP neuron projection in feeding regulation [67]. Another potential complication arises from the fact that DREADDs rely on endogenous G-protein signaling pathways to control neuron functions. Thus, the ability of DREADDs to effectively control neuron activity is determined by a combination of DREADD expression levels, coupling of DREADD and G-protein, and inherent action of the G-protein signaling pathways on the function of the studied neurons. This may be the reason that a wide range of CNO doses are reported to elicit behavioral effects.

12.6. Conclusion

It is noteworthy that an approach that combines light control with intracellular signaling pathways is on the horizon. Based on a chimeric opsin, intracellular signaling can be controlled in a temporally precise manner by light [132, 133]. Stemmed from the light-oxygen-voltage (LOV) family domain of proteins, a variety of LOV-based optogenetic tools for control of intracellular signaling have been proposed and tested [134, 135]. It is without doubt that new approaches such as optogenetics and DREADD have revolutionized our understanding of brain neural circuits in controlling feeding and energy metabolism. With the rapid development of novel technology, more advanced approaches will likely become available and will inevitably expedite our research progress toward more complete understanding of brain control of feeding and provide a mechanistic rationale for effective drug targeting against feeding disorders and associated obesity and diabetes.

Acknowledgments

The research in the Tong lab is supported by grants from the American Heart Association, American Diabetes Foundation, and National Institutes of Health. The research in the Wu lab is supported by the Pew Charitable Trusts, National Institutes of Health, and USDA Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS). Q. Tong is the holder of Cullen Chair in Molecular Medicine and Welch Scholar at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School. Q. Wu is the Pew Scholar of Biomedical Sciences, a Kavli Scholar, and Assistant Professor at the Children’s Nutritional Research Center (CNRC) at Baylor College of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics. Y. Han is a Postdoctoral Fellow from Q. Wu lab. We thank Guobin Xia from Q. Wu lab for assistance to graphics editing. We express our deep appreciations to those scientists who made contributions to the field, but have not been cited due to space limitations.

Contributor Information

Qi Wu, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA; Children’s Nutrition Research Center, Research Service of Department of Agriculture of USA, Houston, TX, USA.

Yong Han, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, USDA-ARS, Houston, TX, USA.

Qingchun Tong, Center for Metabolic and Degenerative Diseases, Brown Foundation Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston, TX, USA.

References

- 1.Limaye A, Hall B, Kulkarni AB (2009) Manipulation of mouse embryonic stem cells for knockout mouse production. Curr Protoc Cell Biol, Chapter 19, Unit 19 13 19 13, 11–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall B, Limaye A, Kulkarni AB (2009) Overview: generation of gene knockout mice. Curr Protoc Cell Biol, Chapter 19, Unit 19 12 19 12, 11–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iacobas DA, Scemes E, Spray DC (2004) Gene expression alterations in connexin null mice extend beyond the gap junction. Neurochem Int 45(2–3):243–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsumoto M et al. (1996) Ataxia and epileptic seizures in mice lacking type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Nature 379(6561):168–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Kieffer BL (2007) Conditional gene targeting in the mouse nervous system: insights into brain function and diseases. Pharmacol Ther 113(3):619–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morozov A, Kellendonk C, Simpson E, Tronche F (2003) Using conditional mutagenesis to study the brain. Biol Psychiatry 54(11):1125–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craig NL (1988) The mechanism of conservative site-specific recombination. Annu Rev Genet 22:77–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagy A (2000) Cre recombinase: the universal reagent for genome tailoring. Genesis 26(2):99–109 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sauer B (1998) Inducible gene targeting in mice using the Cre/lox system. Methods 14(4):381–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sternberg N, Hamilton D, Austin S, Yarmolinsky M, Hoess R (1981) Site-specific recombination and its role in the life cycle of bacteriophage P1. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 45(Pt 1):297–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sternberg N, Hamilton D (1981) Bacteriophage P1 site-specific recombination. I Recombination between loxP sites. J Mol Biol 150(4):467–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoess RH, Ziese M, Sternberg N (1982) P1 site-specific recombination: nucleotide sequence of the recombining sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 79(11):3398–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoess RH, Wierzbicki A, Abremski K (1986) The role of the loxP spacer region in P1 site-specific recombination. Nucleic Acids Res 14(5):2287–2300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang ZJ, Zeng H (2013) Genetic approaches to neural circuits in the mouse. Annu Rev Neurosci 36:183–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madisen L et al. (2010) A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci 13(1):133–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Branda CS, Dymecki SM (2004) Talking about a revolution: the impact of site-specific recombinases on genetic analyses in mice. Dev Cell 6(1):7–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brusa R (1999) Genetically modified mice in neuropharmacology. Pharmacol Res 39(6):405–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewandoski M (2001) Conditional control of gene expression in the mouse. Nat Rev Genet 2(10):743–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells T, Carter DA (2001) Genetic engineering of neural function in transgenic rodents: towards a comprehensive strategy? J Neurosci Methods 108(2):111–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dragatsis I, Levine MS, Zeitlin S (2000) Inactivation of Hdh in the brain and testis results in progressive neurodegeneration and sterility in mice. Nat Genet 26(3):300–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balthasar N et al. (2005) Divergence of melanocortin pathways in the control of food intake and energy expenditure. Cell 123(3):493–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coppari R et al. (2005) The hypothalamic arcuate nucleus: a key site for mediating leptin’s effects on glucose homeostasis and locomotor activity. Cell Metab 1(1):63–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hnasko TS, Sotak BN, Palmiter RD (2005) Morphine reward in dopamine-deficient mice. Nature 438(7069):854–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balthasar N et al. (2004) Leptin receptor signaling in POMC neurons is required for normal body weight homeostasis. Neuron 42(6):983–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gropp E et al. (2005) Agouti-related peptide-expressing neurons are mandatory for feeding. Nat Neurosci 8(10):1289–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sohn JW, Elmquist JK, Williams KW (2013) Neuronal circuits that regulate feeding behavior and metabolism. Trends Neurosci 36(9):504–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramirez S, Claret M (2015) Hypothalamic ER stress: a bridge between leptin resistance and obesity. FEBS Lett 589(14):1678–1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malhotra R, Warne JP, Salas E, Xu AW, Debnath J (2015) Loss of Atg12, but not Atg5, in pro-opiomelanocortin neurons exacerbates diet-induced obesity. Autophagy 11(1):145–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coupe B et al. (2012) Loss of autophagy in pro-opiomelanocortin neurons perturbs axon growth and causes metabolic dysregulation. Cell Metab 15(2):247–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drougard A, Fournel A, Valet P, Knauf C (2015) Impact of hypothalamic reactive oxygen species in the regulation of energy metabolism and food intake. Front Neurosci 9:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diano S, Horvath TL (2012) Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) in glucose and lipid metabolism. Trends Mol Med 18(1):52–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu Q, Boyle MP, Palmiter RD (2009) Loss of GABAergic signaling by AgRP neurons to the parabrachial nucleus leads to starvation. Cell 137(7):1225–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmed BY et al. (2004) Efficient delivery of Cre-recombinase to neurons in vivo and stable transduction of neurons using adeno-associated and lentiviral vectors. BMC Neurosci 5:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dayton RD, Wang DB, Klein RL (2012) The advent of AAV9 expands applications for brain and spinal cord gene delivery. Expert Opin Biol Ther 12(6):757–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berton O et al. (2006) Essential role of BDNF in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway in social defeat stress. Science 311(5762):864–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sainsbury A et al. (2002) Important role of hypothalamic Y2 receptors in body weight regulation revealed in conditional knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99(13):8938–8943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu Q, Clark MS, Palmiter RD (2012) Deciphering a neuronal circuit that mediates appetite. Nature 483(7391):594–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaspar BK et al. (2002) Adeno-associated virus effectively mediates conditional gene modification in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99(4):2320–2325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feil R et al. (1996) Ligand-activated site-specific recombination in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93(20):10887–10890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayashi S, McMahon AP (2002) Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre: a tool for temporally regulated gene activation/inactivation in the mouse. Dev Biol 244(2):305–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madisen L et al. (2015) Transgenic mice for intersectional targeting of neural sensors and effectors with high specificity and performance. Neuron 85(5):942–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris JA et al. (2014) Anatomical characterization of Cre driver mice for neural circuit mapping and manipulation. Front Neural Circuits 8:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smedley D, Salimova E, Rosenthal N (2011) Cre recombinase resources for conditional mouse mutagenesis. Methods 53(4):411–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harno E, Cottrell EC, White A (2013) Metabolic pitfalls of CNS Cre-based technology. Cell Metab 18(1):21–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Magnuson MA, Osipovich AB (2013) Pancreas-specific Cre driver lines and considerations for their prudent use. Cell Metab 18(1):9–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Danielian PS, Muccino D, Rowitch DH, Michael SK, McMahon AP (1998) Modification of gene activity in mouse embryos in utero by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre recombinase. Curr Biol 8(24):1323–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Birling MC, Gofflot F, Warot X (2009) Site-specific recombinases for manipulation of the mouse genome. Methods Mol Biol 561:245–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lexow J, Poggioli T, Sarathchandra P, Santini MP, Rosenthal N (2013) Cardiac fibrosis in mice expressing an inducible myocardial-specific Cre driver. Dis Model Mech 6(6):1470–1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huh WJ, Mysorekar IU, Mills JC (2010) Inducible activation of Cre recombinase in adult mice causes gastric epithelial atrophy, metaplasia, and regenerative changes in the absence of “floxed” alleles. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 299(2):G368–G380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teitelman G, Kedees M (2015) Mouse insulin cells expressing an inducible RIPCre transgene are functionally impaired. J Biol Chem 290(6):3647–3653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meng F et al. (2016) New inducible genetic method reveals critical roles of GABA in the control of feeding and metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113(13):3645–3650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kervestin S, Jacobson A (2012) NMD: a multifaceted response to premature translational termination. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13(11):700–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shalev M, Baasov T (2014) When proteins start to make sense: fine-tuning aminoglycosides for PTC suppression therapy. Medchemcomm 5(8):1092–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nau R, Sorgel F, Eiffert H (2010) Penetration of drugs through the blood-cerebrospinal fluid/blood-brain barrier for treatment of central nervous system infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 23(4):858–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Callaway EM (2008) Transneuronal circuit tracing with neurotropic viruses. Curr Opin Neurobiol 18(6):617–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Callaway EM, Luo L (2015) Monosynaptic circuit tracing with glycoprotein-deleted rabies viruses. J Neurosci 35(24):8979–8985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luo L, Callaway EM, Svoboda K (2008) Genetic dissection of neural circuits. Neuron 57(5):634–660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ginger M, Haberl M, Conzelmann KK, Schwarz MK, Frick A (2013) Revealing the secrets of neuronal circuits with recombinant rabies virus technology. Front Neural Circuits 7:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ugolini G (2011) Rabies virus as a transneuronal tracer of neuronal connections. Adv Virus Res 79:165–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miyamichi K et al. (2011) Cortical representations of olfactory input by trans-synaptic tracing. Nature 472(7342):191–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wickersham IR et al. (2007) Monosynaptic restriction of transsynaptic tracing from single, genetically targeted neurons. Neuron 53(5):639–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wall NR, Wickersham IR, Cetin A, De La Parra M, Callaway EM (2010) Monosynaptic circuit tracing in vivo through Cre-dependent targeting and complementation of modified rabies virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(50):21848–21853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Etessami R et al. (2000) Spread and pathogenic characteristics of a G-deficient rabies virus recombinant: an in vitro and in vivo study. J Gen Virol 81(Pt 9:2147–2153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mebatsion T, Konig M, Conzelmann KK (1996) Budding of rabies virus particles in the absence of the spike glycoprotein. Cell 84(6):941–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wickersham IR, Finke S, Conzelmann KK, Callaway EM (2007) Retrograde neuronal tracing with a deletion-mutant rabies virus. Nat Methods 4(1):47–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arenkiel BR, Ehlers MD (2009) Molecular genetics and imaging technologies for circuit-based neuroanatomy. Nature 461(7266):900–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krashes MJ et al. (2014) An excitatory paraventricular nucleus to AgRP neuron circuit that drives hunger. Nature 507(7491):238–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Knobloch HS et al. (2012) Evoked axonal oxytocin release in the central amygdala attenuates fear response. Neuron 73(3):553–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Osakada F et al. (2011) New rabies virus variants for monitoring and manipulating activity and gene expression in defined neural circuits. Neuron 71(4):617–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kiritani T, Wickersham IR, Seung HS, Shepherd GM (2012) Hierarchical connectivity and connection-specific dynamics in the corticospinal-corticostriatal microcircuit in mouse motor cortex. J Neurosci 32(14):4992–5001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Han X, Boyden ES (2007) Multiple-color optical activation, silencing, and desynchronization of neural activity, with single-spike temporal resolution. PLoS One 2(3):e299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li X et al. (2005) Fast noninvasive activation and inhibition of neural and network activity by vertebrate rhodopsin and green algae channelrhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102(49):17816–17821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang F et al. (2011) The microbial opsin family of optogenetic tools. Cell 147(7):1446–1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lin JY, Lin MZ, Steinbach P, Tsien RY (2009) Characterization of engineered channelrhodopsin variants with improved properties and kinetics. Biophys J 96(5):1803–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yizhar O, Fenno L, Zhang F, Hegemann P, Diesseroth K (2011) Microbial opsins: a family of single-component tools for optical control of neural activity. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2011(3):top102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McIsaac RS, Bedbrook CN, Arnold FH (2015) Recent advances in engineering microbial rhodopsins for optogenetics. Curr Opin Struct Biol 33:8–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lin JY (2011) A user’s guide to channelrhodopsin variants: features, limitations and future developments. Exp Physiol 96(1):19–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Anderson DJ (2012) Optogenetics, sex, and violence in the brain: implications for psychiatry. Biol Psychiatry 71(12):1081–1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Britt JP, Bonci A (2013) Optogenetic interrogations of the neural circuits underlying addiction. Curr Opin Neurobiol 23(4):539–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tourino C, Eban-Rothschild A, de Lecea L (2013) Optogenetics in psychiatric diseases. Curr Opin Neurobiol 23(3):430–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lammel S, Tye KM, Warden MR (2014) Progress in understanding mood disorders: optogenetic dissection of neural circuits. Genes Brain Behav 13(1):38–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sparta DR, Jennings JH, Ung RL, Stuber GD (2013) Optogenetic strategies to investigate neural circuitry engaged by stress. Behav Brain Res 255:19–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sineshchekov OA, Jung KH, Spudich JL (2002) Two rhodopsins mediate phototaxis to low- and high-intensity light in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99(13):8689–8694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nagel G et al. (2003) Channelrhodopsin-2, a directly light-gated cation-selective membrane channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100(24):13940–13945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nagel G et al. (2002) Channelrhodopsin-1: a light-gated proton channel in green algae. Science 296(5577):2395–2398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K (2005) Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat Neurosci 8(9):1263–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nagel G et al. (2005) Light activation of channelrhodopsin-2 in excitable cells of Caenorhabditis elegans triggers rapid behavioral responses. Curr Biol 15(24):2279–2284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Han X (2012) In vivo application of optogenetics for neural circuit analysis. ACS Chem Neurosci 3(8):577–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang F et al. (2007) Multimodal fast optical interrogation of neural circuitry. Nature 446(7136):633–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gradinaru V et al. (2010) Molecular and cellular approaches for diversifying and extending optogenetics. Cell 141(1):154–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Raimondo JV, Kay L, Ellender TJ, Akerman CJ (2012) Optogenetic silencing strategies differ in their effects on inhibitory synaptic transmission. Nat Neurosci 15(8):1102–1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chow BY et al. (2010) High-performance genetically targetable optical neural silencing by light-driven proton pumps. Nature 463(7277):98–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mattis J et al. (2012) Principles for applying optogenetic tools derived from direct comparative analysis of microbial opsins. Nat Methods 9(2):159–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Luquet S, Perez FA, Hnasko TS, Palmiter RD (2005) NPY/AgRP neurons are essential for feeding in adult mice but can be ablated in neonates. Science 310(5748):683–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cone RD (2005) Anatomy and regulation of the central melanocortin system. Nat Neurosci 8(5):571–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Aponte Y, Atasoy D, Sternson SM (2011) AGRP neurons are sufficient to orchestrate feeding behavior rapidly and without training. Nat Neurosci 14(3):351–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Atasoy D, Betley JN, Su HH, Sternson SM (2012) Deconstruction of a neural circuit for hunger. Nature 488(7410):172–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jennings JH, Rizzi G, Stamatakis AM, Ung RL, Stuber GD (2013) The inhibitory circuit architecture of the lateral hypothalamus orchestrates feeding. Science 341(6153):1517–1521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Betley JN, Cao ZF, Ritola KD, Sternson SM (2013) Parallel, redundant circuit organization for homeostatic control of feeding behavior. Cell 155(6):1337–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Carter ME, Soden ME, Zweifel LS, Palmiter RD (2013) Genetic identification of a neural circuit that suppresses appetite. Nature 503(7474):111–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wu Z et al. (2015) GABAergic projections from lateral hypothalamus to paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus promote feeding. J Neurosci 35(8):3312–3318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nieh EH et al. (2015) Decoding neural circuits that control compulsive sucrose seeking. Cell 160(3):528–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Klapoetke NC et al. (2014) Independent optical excitation of distinct neural populations. Nat Methods 11(3):338–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Garfield AS et al. (2015) A neural basis for melanocortin-4 receptor-regulated appetite. Nat Neurosci 18(6):863–871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Allen BD, Singer AC, Boyden ES (2015) Principles of designing interpretable optogenetic behavior experiments. Learn Mem 22(4):232–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Herman AM, Huang L, Murphey DK, Garcia I, Arenkiel BR (2014) Cell type-specific and time-dependent light exposure contribute to silencing in neurons expressing Channelrhodopsin-2. elife 3:e01481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Madisen L et al. (2012) A toolbox of Cre-dependent optogenetic transgenic mice for light-induced activation and silencing. Nat Neurosci 15(5):793–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chuong AS et al. (2014) Noninvasive optical inhibition with a red-shifted microbial rhodopsin. Nat Neurosci 17(8):1123–1129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Grosenick L, Marshel JH, Deisseroth K (2015) Closed-loop and activity-guided optogenetic control. Neuron 86(1):106–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chen Y, Lin YC, Kuo TW, Knight ZA (2015) Sensory detection of food rapidly modulates arcuate feeding circuits. Cell 160(5):829–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Betley JN et al. (2015) Neurons for hunger and thirst transmit a negative-valence teaching signal. Nature 521(7551):180–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.McCall JG et al. (2013) Fabrication and application of flexible, multimodal light-emitting devices for wireless optogenetics. Nat Protoc 8(12):2413–2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rossi MA et al. (2015) A wirelessly controlled implantable LED system for deep brain optogenetic stimulation. Front Integr Neurosci 9:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hashimoto M, Hata A, Miyata T, Hirase H (2014) Programmable wireless light-emitting diode stimulator for chronic stimulation of optogenetic molecules in freely moving mice. Neurophotonics 1(1):011002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Govorunova EG, Sineshchekov OA, Janz R, Liu X, Spudich JL (2015) Natural light-gated anion channels: a family of microbial rhodopsins for advanced optogenetics. Science 349(6248):647–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Urban DJ, Roth BL (2015) DREADDs (designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs): chemogenetic tools with therapeutic utility. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 55:399–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sternson SM, Roth BL (2014) Chemogenetic tools to interrogate brain functions. Annu Rev Neurosci 37:387–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL (2007) Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104(12):5163–5168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Alexander GM et al. (2009) Remote control of neuronal activity in transgenic mice expressing evolved G protein-coupled receptors. Neuron 63(1):27–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sasaki K et al. (2011) Pharmacogenetic modulation of orexin neurons alters sleep/wakefulness states in mice. PLoS One 6(5):e20360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Krashes MJ et al. (2011) Rapid, reversible activation of AgRP neurons drives feeding behavior in mice. J Clin Invest 121(4):1424–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ferguson SM et al. (2011) Transient neuronal inhibition reveals opposing roles of indirect and direct pathways in sensitization. Nat Neurosci 14(1):22–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Guettier JM et al. (2009) A chemical-genetic approach to study G protein regulation of beta cell function in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106(45):19197–19202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Farrell MS et al. (2013) A Galphas DREADD mouse for selective modulation of cAMP production in striatopallidal neurons. Neuropsychopharmacology 38(5):854–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zhu H et al. (2014) Chemogenetic inactivation of ventral hippocampal glutamatergic neurons disrupts consolidation of contextual fear memory. Neuropsychopharmacology 39(8):1880–1892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Krashes MJ, Shah BP, Koda S, Lowell BB (2013) Rapid versus delayed stimulation of feeding by the endogenously released AgRP neuron mediators GABA, NPY, and AgRP. Cell Metab 18(4):588–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zhan C et al. (2013) Acute and long-term suppression of feeding behavior by POMC neurons in the brainstem and hypothalamus, respectively. J Neurosci 33(8):3624–3632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Rezai-Zadeh K et al. (2014) Leptin receptor neurons in the dorsomedial hypothalamus are key regulators of energy expenditure and body weight, but not food intake. Mol Metab 3(7):681–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Li AJ, Wang Q, Elsarelli MM, Brown RL, Ritter S (2015) Hindbrain catecholamine neurons activate orexin neurons during systemic glucoprivation in male rats. Endocrinology 156(8):2807–2820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Stachniak TJ, Ghosh A, Sternson SM (2014) Chemogenetic synaptic silencing of neural circuits localizes a hypothalamus→midbrain pathway for feeding behavior. Neuron 82(4):797–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kong D et al. (2012) GABAergic RIP-Cre neurons in the arcuate nucleus selectively regulate energy expenditure. Cell 151(3):645–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Airan RD, Thompson KR, Fenno LE, Bernstein H, Deisseroth K (2009) Temporally precise in vivo control of intracellular signalling. Nature 458(7241):1025–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.van Bergeijk P, Adrian M, Hoogenraad CC, Kapitein LC (2015) Optogenetic control of organelle transport and positioning. Nature 518(7537):111–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Pudasaini A, El-Arab KK, Zoltowski BD (2015) LOV-based optogenetic devices: light-driven modules to impart photoregulated control of cellular signaling. Front Mol Biosci 2:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Grosse R (2015) LOV is all we need. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 16(4):206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]