Abstract

n-Butanol is a renewable resource with a wide range of applications. Its physicochemical properties make it a potential substitute for gasoline. Saccharomyces cerevisiae can produce n-butanol via amino acid catabolic pathways, but the use of pure amino acids is economically unfeasible for large-scale production. The aim of this study was to optimize the production of n-butanol by S. cerevisiae from protein-rich agro-industrial by-products (sunflower and poultry offal meals). By-products were characterized according to their total protein and free amino acid contents and subjected to enzymatic hydrolysis. Protein hydrolysates were used as nitrogen sources for the production of n-butanol by S. cerevisiae, but only poultry offal meal hydrolysate (POMH) afforded detectable levels of n-butanol. Under optimized conditions (carbon/nitrogen ratio of 2 and working volume of 60%), 59.94 mg/L of n-butanol was produced using POMH and glucose as substrates. The low-cost agro-industrial by-product showed great potential to be used in the production of n-butanol by S. cerevisiae. Other protein-rich residues may also find application in biofuel production by yeasts.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s42770-020-00370-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Biofuel, Nitrogen source, Optimization

Introduction

Global concern about climate change and the need to replace fossil fuels have motivated the scientific community to search for environmentally friendly energy sources [1]. Biofuels are a promising substitute for fossil fuels because they can be produced by fermentation of renewable materials [2]. Large-scale ethanol production has become possible due to technological advances. Although it is the most widely used biofuel today, ethanol is not considered the best substitute for gasoline. Butanol, a higher alcohol with four carbons and four isomers (n-butanol, sec-butanol, isobutanol, and tert-butanol) has some important advantages over ethanol [3]. In comparison with ethanol, butanol has higher blending ability with gasoline and energy density and is less volatile and more hydrophobic. Its main disadvantage is the low yield of fermentation reactions [4, 5]. Microorganisms of the genus Clostridium naturally produce butanol via acetone–butanol–ethanol fermentation. Their low tolerance to butanol, however, leads to low metabolite production (13–14 g/L). Therefore, Clostridium species are not indicated for industrial-scale production of this alcohol [6, 7]. Other microorganisms, such as Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, have been investigated for their ability to produce n-butanol [1].

S. cerevisiae is widely used in the food and ethanol industries. A vast range of genetic tools are available for the yeast, and it is highly tolerant to higher alcohols [8, 9]. S. cerevisiae can produce n-butanol by heterologous expression of the clostridial pathway or by amino acid catabolism via the Ehrlich pathway [3, 5, 8, 10].

Previous studies have shown that amino acids can boost S. cerevisiae n-butanol production by acting as cosubstrates in fermentation [5, 8, 9, 11]. To date, all studies have used pure amino acids, such as glycine and threonine, as sources of nitrogen, but their high costs make large-scale butanol production unfeasible. An interesting alternative is the use of a low-cost amino acid source [11], for instance, protein-rich agro-industrial by-products. However, a proteolysis pretreatment step is required to degrade polypeptides into hydrolysates which the microorganism can uptake [12, 13].

The aim of this study was to optimize the production of n-butanol by S. cerevisiae using agro-industrial by-products as a source of amino acids. Sunflower and poultry offal meals were hydrolyzed to increase the availability of peptides and free amino acids, and fermentation process parameters were investigated to increase n-butanol yield.

Material and methods

Agro-industrial by-products

Sunflower meal was kindly supplied by the Institute of Food Technology (Campinas, Brazil) and poultry offal meal (FVA) by Patense® (Adamantina, Brazil).

Optimization of enzymatic hydrolysis

Enzymatic hydrolysis of agro-industrial by-products was performed using a commercial endoprotease produced by Bacillus licheniformis (Alcalase® 2.4 L, Novozyme®, Bagsvaerd, Denmark). This enzyme not only has been present a high protease activity but a considerable resistance to autoproteolysis due to its current production and commercialization with post-translational modifications [12, 14]. Tests were carried out in 250-mL Erlenmeyer flasks under moderate agitation using a 1:16 (sunflower meal/water) or 1:10 (poultry offal meal/water) solid-to-liquid ratio. A central composite rotatable design (CCRD) was used to determine the optimal process conditions for free amino acid production. Three factors were evaluated, pH (6.3–9.7), temperature (50–70 °C), and enzyme concentration (0.5–5.5% v/v), with 6 axial points and 3 repetitions of the center point, totaling 17 runs. The effects of independent variables on the dependent variable (degree of hydrolysis) were analyzed using Protimiza Experimental Design [15] (https://experimental-design.protimiza.com.br/).

Selection of protein hydrolysate for n-butanol production

Protein hydrolysates were prepared by enzymatic hydrolysis under the optimal conditions determined for each agro-industrial by-product. Hydrolysates were used as a nitrogen source for the production of n-butanol by S. cerevisiae UFMG-CM-Y267, a strain isolated from a Tapirira guianensis tree in Tocantins, Brazil [16]. The strain was previously shown to produce n-butanol [17].

The fermentation medium (pH 6) was composed of 20 g/L glucose and protein hydrolysates diluted in sterile distilled water to a final concentration of 15 g/L protein [11]. Cells cultured in YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose, and 2% agar) were incubated in a 500-mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 100 mL YPD broth at 30 °C and 200 rpm for 12 h. Cells were centrifuged (2500×g for 10 min), washed with sterile distilled water, and transferred to the fermentation medium at an initial optical density of 0.1 at 600 nm (OD600). Fermentations were carried out in triplicate under semi-anaerobic conditions in 2-mL Eppendorf tubes containing 2 mL of medium with a minimal amount of headspace. Tubes were incubated in a dry bath heater (Loccus DBH-S, Loccus, Cotia, Brazil) at 30 °C under agitation (800 rpm) for 72 h. The concentrations of glucose, n-butanol, isobutanol, ethanol, and acetic acid were determined after fermentation.

Optimization of fermentation parameters

A second CCRD was used to evaluate the effects carbon–nitrogen (C/N) ratio (2–58 mol/mol) and working volume (20–80% v/v) on n-butanol and isobutanol production by S. cerevisiae from poultry offal meal hydrolysate (POMH). A total of 11 runs were performed, with 4 axial points and 3 repetitions of the center point. The effects of independent variables were analyzed using Protimiza Experimental Design [15] (https://experimental-design.protimiza.com.br/). The C/N ratio was calculated on the basis of the carbon content of glucose and not of amino acids because the carbon atoms of n-butanol are obtained from glucose, whereas amino acids act as cosubstrates [8].

The fermentation medium was composed of 1.73 g/L POMH and different concentrations of glucose. The inoculum was prepared as described above (see section Selection of protein hydrolysate for n-butanol production), and fermentations were carried out in 50-mL Falcon tubes with different working volumes at 30 °C for 84 h under constant agitation of 250 rpm. The concentrations of n-butanol and isobutanol were determined after fermentation.

Analytical methods

Quantification of total protein and free amino acids

Agro-industrial by-products and their hydrolysates were characterized according to their total protein content and free amino acid profile. Hydrolysates were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was collected. Total protein was determined by the Kjeldahl method [18] using a nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor of 6.25.

Total amino acids were quantified by reverse-phase chromatography using a high efficiency liquid chromatograph (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), according to the methods of White et al. [19] and Hagen et al. [20]. Amino acids were identified and quantified by comparison with their retention times to those of an external standard (Pierce PN 20088, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, USA) and an internal standard (α-aminobutyric acid, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, USA), respectively, according to White et al. [19] and Hagen et al. [20]. For free amino acid determination, amino acids were extracted with 0.1 M HCl under agitation for 30 min. An aliquot of the filtrate was derivatized by the same method used for total amino acid determination (excepting acid hydrolysis).

Tryptophan concentration was determined after enzymatic hydrolysis with pronase (40 °C for 22–24 h) by a colorimetric method using 4-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde in 10.55 mol/L sulfuric acid (H2SO4). Samples were read at 590 nm, and tryptophan levels were calculated using a standard curve of l-tryptophan [21].

Determination of degree of hydrolysis

Degree of hydrolysis (DH), or percentage of cleaved peptide bonds, was determined by the pH-stat method, based on the titration of α-amino groups released during enzymatic hydrolysis under constant pH and temperature. DH was calculated using Eq. (1) [22]:

| 1 |

where B is the volume (mL) of NaOH solution consumed during hydrolysis to maintain the pH, Nb is the normality of the base, Mp is the protein mass (g, calculated as nitrogen content × Kjeldahl factor), htotal is the total number of peptide bonds prior to the reaction (for most proteins, htotal corresponds to 8 mol equiv./kg), and α is the degree of dissociation of α-amino groups, or the proportionality factor, which was calculated using Eq. (2):

| 2 |

According to Steinhart and Beychok [23] and Kristinsson and Rasco[24], pKa can be calculated using Eq. (3):

| 3 |

where T is the temperature in K.

Quantification of glucose and metabolic products

Samples were filtered through a PVDF Millex® GV Durapore® membrane (0.22 μm, Millipore, Massachusetts, USA) for determination of n-butanol, isobutanol, ethanol, acetic acid, and glucose concentrations. Quantification was performed using a high-performance liquid chromatograph equipped with a HyperREZ XP column at 60 °C (Thermo Fischer Scientific, USA) and a refractive index detector at 50 °C using 5 mM H2SO4 as the mobile phase at 0.6 mL/min. Calibration curves were constructed using standard solutions (Sigma–Aldrich, USA).

Results and discussion

Characterization of agro-industrial by-products

Agro-industrial by-products are available in large quantities and frequently contain industrially and economically important compounds. By-products can be used in bioprocesses to reduce both costs and environmental impacts [25]. Sunflower meal and poultry offal meal were chosen for their high protein content [26], a desired property for protein hydrolysate production and, subsequently, production of n-butanol by S. cerevisiae. The total protein content and free amino acid profile of the by-products are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Protein content and Amino acid profile of poultry offal and sunflower meals

| Agro-industrial by-product | ||

|---|---|---|

| Poultry offal meal | Sunflower meal | |

| Protein content | ||

| Total protein (%) | 62.72a ± 0.24 | 62.05a ± 0.25 |

| Amino acid profile (g amino acid/100 g sample) | ||

| Aspartic acid | 5.00 | 4.01 |

| Glutamic acid | 13.58 | 8.34 |

| Serine | 2.58 | 2.74 |

| Glycine | 3.16 | 5.58 |

| Histidine | 1.43 | 1.49 |

| Arginine | 6.33 | 5.24 |

| Threonine | 2.29 | 3.32 |

| Alanine | 2.29 | 3.50 |

| Proline | 2.41 | 4.19 |

| Tyrosine | 1.58 | 1.68 |

| Valine | 3.01 | 2.83 |

| Methionine | 0.86 | 1.27 |

| Cystine | 0.37 | 0.24 |

| Isoleucine | 2.46 | 2.73 |

| Leucine | 3.58 | 3.43 |

| Phenylalanine | 2.58 | 1.97 |

| Tryptophan | 1.10 | 0.93 |

| Lysine | 1.98 | 3.55 |

The total protein means followed by the same letter (a) do not differ significantly (p > 0.05) by Tukey’s test

Agro-industrial by-products did not differ in protein content, and their amino acid profiles were relatively similar (Table 1). Rostagno et al. [27] reported lower crude protein contents than those observed in this study: 37.50% in sunflower meal and 47.80% in poultry offal meal. These differences are likely due to differences in processing conditions, plant variety, growth season, and genetic factors of source materials [28]. Studies have shown that alanine, glycine, threonine, serine, and valine act as cosubstrates in n-butanol production by yeasts [8, 11, 29, 30]. Together, these cosubstrates were detected at 17.97% in poultry offal meal and 13.33% in sunflower meal. Therefore, the by-products were deemed appropriate for the production of protein hydrolysates to be used as substrates for fermentation.

Enzymatic hydrolysis of agro-industrial by-products

Optimization of enzymatic hydrolysis

Sunflower and poultry offal meals were subjected to enzymatic hydrolysis to solubilize proteins, thereby improving the availability of amino acids for assimilation by S. cerevisiae during fermentation. According to Kurozawa et al. [22], enzyme specificity, pH, reaction temperature, and substrate are important parameters affecting the efficiency of enzymatic hydrolysis. CCRD and response surface methodology were applied to determine the optimal temperature, pH, and enzyme concentration for high yields of free amino acids and low molecular weight peptides. The response variable was the DH. Preliminary kinetic analysis shows that the best reaction times for sunflower and poultry offal meals were 2 and 3 h of hydrolysis, respectively (Figs. S1 and S2, Supplementary material).

CCRD levels and experimental results are shown in Table 2. The maximum DH was 31.98% (run 12) in sunflower meal and 31.32% (run 7) in poultry offal meal. Sunflower meal required lower enzyme concentrations than poultry offal meal to achieve similar DH values. The highest response for sunflower meal was obtained using pH 9.7 (+ 1.68), indicating that the substrate is more soluble at alkaline pH. Runs 15, 16, and 17 (center point) showed similar results, demonstrating good reproducibility of the experiments.

Table 2.

Central composite rotatable design matrix showing coded and actual values of process parameters and their effects on the response variable, degree of hydrolysis (DH)

| Run | Temperature (°C) | pH | % Enzyme (v/v) | DH (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunflower meal | Poultry offal meal | ||||

| 1 | 54 (− 1) | 7.0 (− 1) | 1.5 (− 1) | 16.22 | 21.43 |

| 2 | 66 (+ 1) | 7.0 (− 1) | 1.5 (− 1) | 13.97 | 18.34 |

| 3 | 54 (− 1) | 9.0 (+ 1) | 1.5 (− 1) | 16.98 | 25.74 |

| 4 | 66 (+ 1) | 9.0 (+ 1) | 1.5 (− 1) | 12.14 | 20.32 |

| 5 | 54 (− 1) | 7.0 (− 1) | 4.5 (+ 1) | 22.59 | 24.91 |

| 6 | 66 (+ 1) | 7.0 (− 1) | 4.5 (+ 1) | 20.52 | 23.14 |

| 7 | 54 (− 1) | 9.0 (+ 1) | 4.5 (+ 1) | 20.43 | 31.32 |

| 8 | 66 (+ 1) | 9.0 (+ 1) | 4.5 (+ 1) | 19.27 | 27.45 |

| 9 | 50 (− 1.68) | 8.0 (0) | 3.0 (0) | 16.87 | 22.90 |

| 10 | 70 (+ 1.68) | 8.0 (0) | 3.0 (0) | 13.00 | 20.19 |

| 11 | 60 (0) | 6.3 (− 1.68) | 3.0 (0) | 16.32 | 28.68 |

| 12 | 60 (0) | 9.7 (+ 1.68) | 3 (0) | 31.98 | 26.53 |

| 13 | 60 (0) | 8.0 (0) | 0.5 (− 1.68) | 15.98 | 20.28 |

| 14 | 60 (0) | 8.0 (0) | 5.5 (+ 1.68) | 31.48 | 27.42 |

| 15 | 60 (0) | 8.0 (0) | 3.0 (0) | 29.13 | 27.42 |

| 16 | 60 (0) | 8.0 (0) | 3.0 (0) | 28.19 | 27.99 |

| 17 | 60 (0) | 8.0 (0) | 3.0 (0) | 29.13 | 27.42 |

CCRD allows using coded values to generate regression models and eliminate non-significant coefficients [15]. Models were generated on the basis of CCRD results, and coefficients were evaluated at p < 0.10. The second-order models for sunflower meal and poultry offal meal are represented by Eqs. (4) and (5), respectively:

| 4 |

| 5 |

where x1 is the temperature (°C), x2 is the pH, and x3 is the enzyme concentration (%).

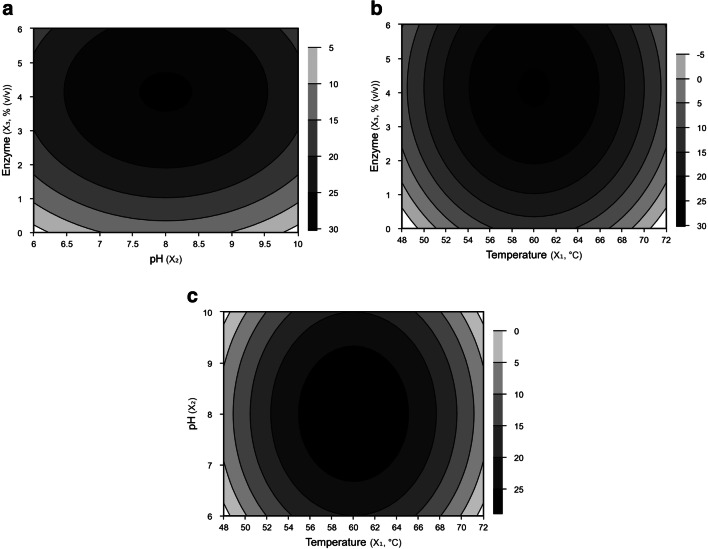

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) is performed for each substrate to verify the validity of regression coefficients and mathematical models (Tables S1 and S2, Supplementary material). For both by-products, the F value was higher than the F critical (4 times higher for sunflower meal and 5 times higher for poultry offal meal), and the coefficient of determination (R2) was higher than 74%, indicating that predicted values agree satisfactorily with experimental results. Figures 1 and 2 show the response surface contour plots of DH as a function of pH, temperature, and enzyme concentration. DH was significantly affected by all variables. The optimal enzyme concentration for poultry offal meal (2.80%, Fig. 1a and b) is lower than that for sunflower meal (3.64%, Fig. 2a and b). This result may be explained by the higher percentage of amino acids in poultry offal meal than in sunflower meal (Table 1). At pH 7.5 to 8.0 and temperatures of 55 to 60 °C―optimal conditions for enzyme activity and protein solubility [12]―a high DH can be achieved using lower enzyme concentrations.

Fig. 1.

Contour plots of degree of hydrolysis of poultry offal meal as a function of enzyme concentration and pH (a), enzyme concentration and temperature (b), and pH and temperature (c)

Fig. 2.

Contour plots of degree of hydrolysis of sunflower meal as a function of enzyme concentration and pH (a), enzyme concentration and temperature (b), and pH and temperature (c)

Models are validated by carrying out enzymatic hydrolysis under the optimal conditions for each by-product, as shown in Table 3. Experimental results were similar to predicted values, demonstrating that the optimization was successful. Kinetic curves are constructed for each substrate (Figs. S1 and S2, Supplementary material). Hydrolysis occurred more rapidly during the first 60 min for both substrates, decreasing gradually until reaching a plateau in 120 and 180 min of reaction for sunflower and poultry offal meals, respectively.

Table 3.

Predicted and experimental values of degree of hydrolysis (DH) of sunflower meal (SM) and poultry offal meal (POM)

| Substrate | Variable | DH (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | pH | % Enzyme (v/v) | Predicted value | Experimental value | |

| SM | 60 | 8.0 | 3.7 | 27.86 | 30.08 ± 2.30 |

| POM | 60 | 8.0 | 3.0 | 29.23 | 27.60 ± 0.78 |

The results corroborate those of Villanueva et al. [31], who achieved a DH of 34.7% using Alcalase for enzymatic hydrolysis of a protein isolate of sunflower meal, and of Ordóñes et al. [32], who reported a DH of 37.8% using Alcalase (endopeptidase) and Flavourzyme (exopeptidase) to hydrolyze sunflower meal. Taheri et al. [33] reported a lower DH (26.14%) for poultry head and leg meal than that of the present study. The authors used Alcalase at 45.53 °C, pH 8.5, 0.5 a.u. enzyme/g protein, and reaction time of 85.13 min.

Hydrolysate characterization

The protein content and free amino acid profile of hydrolysates were evaluated. POMH and sunflower meal hydrolysate (SMH) had protein contents of 66.25 ± 0.77 g/L and 62.13 ± 0.67 g/L, respectively. SMH had a darker color than POMH because it is rich in phenolics, such as chlorogenic acid. This compound has a greenish color in alkaline medium and can darken with oxidation [34].

The amino acid profiles of both hydrolysates are shown in Table 4. Although hydrolysates had a high protein content (above 60%), the concentration of free amino acids was not high. This was likely due to the formation of peptides rather than free amino acids during enzymatic hydrolysis. S. cerevisiae can consume peptides, as it contains specific permeases to transport amino acid by-products across the plasma membrane [35]. According to Huo et al. [36], protein hydrolysates are defined as a mixture of amino acids and peptides and can be successfully used for the production of biofuel via the Ehrlich pathway.

Table 4.

Amino acid profile of poultry offal meal hydrolysate (POMH) and sunflower meal hydrolysate (SMH)

| Amino acid | POMH | SMH |

|---|---|---|

| (g amino acid/100 g sample) | ||

| Aspartic acid | 0.01915 | 0.01559 |

| Glutamic acid | 0.02361 | 0.04254 |

| Serine | 0.01987 | 0.02807 |

| Glycine | 0.00376 | 0.00601 |

| Histidine | 0.06639 | 0.02525 |

| Arginine | 0.03782 | 0.03806 |

| Threonine | 0.02561 | 0.02875 |

| Alanine | 0.00878 | 0.04811 |

| Proline | 0.09312 | 0.01883 |

| Tyrosine | 0.00595 | 0.01155 |

| Valine | 0.01844 | 0.07062 |

| Methionine | 0.00830 | 0.03863 |

| Cystine | 0.00268 | 0.00914 |

| Isoleucine | 0.08239 | 0.24956 |

| Leucine | 0.01051 | 0.03327 |

| Phenylalanine | 0.03497 | 0.14308 |

| Tryptophan | 0.01864 | 0.06959 |

| Lysine | 0.02106 | 0.07088 |

| Total | 0.5252 | 10.162 |

Production of n-butanol from agro-industrial by-products

Selection of protein hydrolysate for the production of n-butanol

Fermentation tests were carried out to select the best protein hydrolysate for n-butanol production by S. cerevisiae. The fermentation medium was designed to contain a final concentration of soluble proteins of 15 g/L, following the recommendations of Branduardi et al. [11]. Glucose consumption and metabolite production after 72 h of fermentation are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Glucose consumption and n-butanol, isobutanol, ethanol, and acetic acid concentrations after 72 h of fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae UFMG-CM-Y267 using protein hydrolysates as substrates

| Protein hydrolysate | Glucose (g/L) |

n-Butanol (mg/L) |

Isobutanol (mg/L) |

Ethanol (g/L) |

Acetic acid (g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POMH | 0.03 ± 0.002 | 42.66 ± 2.63 | 32.76 ± 1.47 | 8.61 ± 0.04 | 0.35 ± 0.01 |

| SMH | nd | nd | 10.33 ± 1.44 | 8.77 ± 0.15 | 0.87 ± 0.09 |

POMH, poultry offal meal hydrolysate; SMH, sunflower meal hydrolysate; nd, not detected

Yeasts were able to grow in the fermentation media, as evidenced by metabolite production and the almost complete consumption of glucose. In addition to n-butanol concentration, ethanol and acetic acid concentrations were determined, as they are common metabolites of S. cerevisiae fermentation. Isobutanol, a butanol isomer, is also known to be produced by the yeast. As expected, ethanol was the major metabolite, followed by acetic acid and butanol isomers. S. cerevisiae is a well-known ethanol producer, and higher alcohols are considered by-products of fermentation [37]. The native amino acid degradation pathways present in yeasts support only a small amount of higher alcohols [36].

POMH resulted in the production of 42.66 mg/L n-butanol and 32.76 mg/L isobutanol. On the other hand, yeasts were not able to produce n-butanol at detectable levels from SMH, and the concentration of isobutanol was lower than that obtained from POMH.

When broken down via the Ehrlich pathway, different amino acids result in the formation of different higher alcohols. For instance, n-butanol is produced from glycine, serine, cysteine, alanine, and tryptophan; isobutanol from valine; 2-methyl-1-butanol from isoleucine; 3-methyl-1-butanol from leucine; 2-phenylethanol from phenylalanine; and tyrosol from tyrosine residues [36, 38, 39]. POMH had a higher concentration of n-butanol and isobutanol precursors (glycine, serine, cysteine, alanine, tryptophan, and valine) (Table 4). Therefore, it was selected to be used for the optimization of n-butanol production.

Optimization of n-butanol production by S. cerevisiae from POMH

In this step, we sought to optimize fermentation parameters for high n-butanol production. A 22 CCRD is used to assess the effects of C/N ratio and working volume on n-butanol and isobutanol concentrations (Table 6).

Table 6.

Central composite rotatable design matrix showing coded and actual values and experimental results

| Run | C/N ratio | Working volume (%) | n-Butanol (mg/L) | Isobutanol (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 (− 1) | 29 (− 1) | nd | 56.41 |

| 2 | 50 (+ 1) | 29 (− 1) | 34.01 | 288.96 |

| 3 | 10 (− 1) | 71 (+ 1) | 51.33 | 65.77 |

| 4 | 50 (+ 1) | 71 (+ 1) | 35.25 | 291.90 |

| 5 | 2 (− 1.41) | 50 (0) | 65.44 | 16.32 |

| 6 | 58 (+ 1.41) | 50 (0) | 46.33 | 302.01 |

| 7 | 30 (0) | 20 (− 1.41) | nd | 119.20 |

| 8 | 30 (0) | 80 (+ 1.41) | nd | 209.97 |

| 9 | 30 (0) | 50 (0) | 48.20 | 204.06 |

| 10 | 30 (0) | 50 (0) | 59.67 | 204.45 |

| 11 | 30 (0) | 50 (0) | 51.04 | 195.21 |

nd, not detected

Surface response contour plots are generated on the basis of CCRD results (Fig. 3). The validity of regression models and coefficients (Eqs. (6) and (7)) is tested by ANOVA (Tables S3 and S4, Supplementary material).

| 6 |

| 7 |

where x1 is the C/N ratio (mol/mol) and x2 is the working volume (%). The F value was higher than the F critical, and R2 values were 88.20% for n-butanol and 95.19% for isobutanol.

Fig. 3.

Contour plots of n-butanol (a) and isobutanol (b) concentrations as a function of C/N ratio (mol/mol) and working volume (%)

Run 5 and center point runs (9, 10, and 11), carried out with a working volume of 50%, afforded the highest n-butanol concentrations. Runs 7 (20% working volume) and 8 (80% working volume), carried out using a C/N ration of 30, resulted in undetectable levels of the higher alcohol. The results suggest that reaction volume has a substantial effect on n-butanol production. In Eq. (6), linear and quadratic terms of working volume (x2 and x22) and the interaction term (x1x2) are statistically significant at p < 0.10.

Figure 3a shows that n-butanol production is negatively affected at working volumes lower than 40%, i.e., with more oxygen available, regardless of C/N ratio. On the other hand, at working volumes above 70%, i.e., under oxygen limitation, n-butanol concentration increases with decreasing C/N ratios. Therefore, the optimal conditions are working volume of 57–68% and C/N ratio of 0.2–3.

To then estimate the concentration of n-butanol under optimal conditions, we selected a working volume of 60% and a C/N ratio of 2 (7.5 g/L glucose + 1.73 g/L nitrogen) and the model predicted a n-butanol concentration of 60.35 mg/L. Experimental tests carried out under the optimal conditions resulted in a concentration of 62.11 ± 0.92 mg/L, close to the predicted value. Run 5 yielded a higher n-butanol concentration than the predicted and validated under optimized conditions. The results of the center point (runs 9, 10, and 11) had a standard deviation of 5.97 mg/L, showing that the high concentration afforded in run 5 might have been due to analytical error.

Run 6 afforded the highest concentration of isobutanol (302.01 mg/L), probably because of the high initial glucose concentration used. The opposite was observed in run 5: low initial glucose concentration resulted in the lowest isobutanol yield. Equation (7) and Fig. 3b show that isobutanol production is directly proportional to C/N ratio and is little affected by working volume (or oxygen availability), contrary to the observed for n-butanol production.

Gutierrez [37], studying the production of isobutanol by fermentation, observed a significant effect of sucrose concentration on alcohol formation. According to the author, nitrogen deficiency, caused by the high concentration of the carbon source (i.e., higher C/N ratio), increased isobutanol production. The same behavior was observed by Äyräpää [40] when studying the influence of nitrogen source concentration on the formation of higher alcohols by Saccharomyces pastorianus.

Within the study range adopted, the highest isobutanol yield (360 mg/L) could be achieved using a 65–80% working volume and a 57–60 C/N ratio. However, because the focus of this study was n-butanol production, the isobutanol model was not experimentally validated.

S. cerevisiae UFMG-CM-Y267, a non-modified wild strain identified capable of producing n-butanol from glycine (15 g/L) and glucose (20 g/L), was used in this study. Azambuja et al. [17] evaluated 48 S. cerevisiae strains and observed that different strains have different metabolite production profiles. The authors reported that this same strain (UFMG-CM-Y267), when grown on glucose and glycine, produced 12.7 mg/L n-butanol, about 5 times lower than that obtained in this study using POMH (59.94 mg/L n-butanol) containing a variety of amino acids.

In the study by Branduardi et al. [11], the authors proposed a metabolic route for the production of n-butanol by the yeast S. cerevisiae when carbon was used as a carbon source and glycine as a nitrogen source. In this work, the authors speculated that the amino acid glycine acted as a booster for the carbon flow to be directed to the production of butanol, being then considered a fermentation cosubstrate. Later, in the work published by Si et al. [8], the authors carried out a fermentation carbon-labeled glucose (D-glucose-13C6) and glycine (L-glycine-2-13C) and confirmed the hypothesis of the previous article by demonstrating that all butanol produced was from glucose and that glycine acted as a cosubstrate.

Research to date has shown that the production of n-butanol by S. cerevisiae is still well below the concentrations obtained by species of Clostridium. However, the production of this alcohol using bacteria presents several problems due to the need for strictly anaerobic cultures, low growth rate, and spore formation [41, 42]. Thus, the yeast S. cerevisiae has become a promising option to be evaluated. On the other hand, as demonstrated in this and other studies, the production of n-butanol by S. cerevisiae is still much lower than the production of ethanol. However, knowing that butanol has been considered as the best substitute for gasoline, the production of this alcohol deserves and demands more studies so that in the future, the industrial production of butanol can become reality.

Our results also showed that n-butanol production by S. cerevisiae depends on the catabolism of specific amino acids. However, to achieve high yields, great availability of these nitrogen sources is necessary. The wild-type yeast studied (i.e., does not have any type of genetic modification to increase the production of butanol) was able to produce n-butanol in higher concentration in the presence of a variety of amino acids, when compared with only glycine. Thus, in this work, we speculate that the presence of several amino acids is preferable over the presence of a single amino acid. Moreover, protein-rich by-products are potential sources of amino acids and can contribute to reducing butanol production costs. So far, this work is the second already published evaluating wild-type strains for the production of n-butanol and the first to use agro-industrial by-products as a source of nitrogen to reduce raw material costs.

Conclusion

Enzymatic hydrolysis of poultry offal meal under optimized conditions resulted in an interesting source of amino acids for n-butanol production by S. cerevisiae. An n-butanol concentration of 59.94 mg/L was achieved under optimal C/N ratios and working volumes. Agro-industrial by-products are a low-cost source of a mixture of amino acids. Their use in n-butanol production can decrease production costs and add value to agro-industrial wastes.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 280 kb)

Funding

The authors thank the São Paulo State Research Foundation (FAPESP) for the financial support (grants nos. 2015/50612-8, 2015/20630-4, 2016/04602-3 and 2019/08542-3) and Dr. Maria Teresa Bertoldo Pacheco from the Institute of Food Technology, Campinas, Brazil, for kindly providing the sunflower meal.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chen CT, Liao JC. Frontiers in microbial 1-butanol and isobutanol production. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2016;363:1–13. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnw020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Branduardi P, Porro D. n-butanol: challenges and solutions for shifting natural metabolic pathways into a viable microbial production. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2016;363:1–7. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnw070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuroda K, Ueda M. Cellular and molecular engineering of yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae for advanced biobutanol production. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2016;363:1–24. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnv247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi YJ, Lee J, Jang YS, Lee SY. Metabolic engineering of microorganisms for the production of higher alcohols. mBio. 2014;5:1–10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01524-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swidah R, Wang H, Reid PJ, et al. Butanol production in S. cerevisiae via a synthetic ABE pathway is enhanced by specific metabolic engineering and butanol resistance. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2015;8:97. doi: 10.1186/s13068-015-0281-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steen EJ, Chan R, Prasad N, Myers S, Petzold CJ, Redding A, Ouellet M, Keasling JD. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the production of n-butanol. Microb Cell Factories. 2015;7:36. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-7-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang Y, Liu J, Jiang W, Yang Y, Yang S. Current status and prospects of industrial bio-production of n-butanol in China. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;33:1493–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Si T, Luo Y, Xiao H, Zhao H. Utilizing an endogenous pathway for 1-butanol production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab Eng. 2014;22:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi S, Si T, Liu Z, Zhang H, Ang EL, Zhao H. Metabolic engineering of a synergistic pathway for n-butanol production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25675. doi: 10.1038/srep25675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hazelwood LA, Daran JM, van Maris AJ, et al. The Ehrlich pathway for fusel alcohol production: a century of research on Saccharomyces cerevisiae metabolism. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:2259–2266. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02625-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Branduardi P, Longo V, Berterame NM, Rossi G, Porro D. A novel pathway to produce butanol and isobutanol in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6:68. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-6-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt CG, Salas-Mellado M. Influence of alcalase and flavourzyme performance on the degree of hydrolysis of the proteins of chicken meat. Quím Nova. 2009;32:1144–1150. doi: 10.1590/S0100-40422009000500012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi KY, Wernick DG, Tat CA, Liao JC. Consolidated conversion of protein waste into biofuels and ammonia using Bacillus subtilis. Met Eng. 2014;23:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furlani IL, Amaral BS et al (2020) Imobilização enzimática: Conceito e efeitos na proteólise. Quím Nova:1–11. 10.21577/0100-4042.20170525

- 15.Rodrigues MI, Iemma AF (2014) Experimental design and process optimization. CRC Press

- 16.Barbosa R, Almeida P, Safar SVB, Santos RO, Morais PB, Nielly-Thibault L, Leducq JB, Landry CR, Gonçalves P, Rosa CA, Sampaio JP. Evidence of natural hybridization in Brazilian wild lineages of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8:317–329. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azambuja SPH, Teixeira GS, Andrietta MGS, Torres-Mayanga PC, Forster-Carneiro T, Rosa CA, Goldbeck R. Analysis of metabolite profiles of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains suitable for butanol production. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2019;366:1–7. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnz164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Instituto Adolfo Lutz (2008) Métodos físico-químicos para análise de alimentos, São Paulo 4:-1020

- 19.White JA, Hart RJ, Fry JC. An evaluation of the waters Pico-tag system for the amino-acid analysis of food materials. J Anal Met Chem. 1986;8:170–177. doi: 10.1155/S1463924686000330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagen SR, Frost B, Augustin J. Precolumn phenylisothiocyanate derivatization and liquid chromatography of amino acids in food. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1989;72:912–916. doi: 10.1016/0308(93)90-8146127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spies JR. Determination of tryptophan in proteins. Anal Chem. 1967;39:1412–1416. doi: 10.1021/ac60256a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurozawa LE, Park KJ, Hubinger MD. Influência das condições de processo na cinética de hidrólise enzimática de carne de frango. Ciênc Tecnol Aliment. 2009;29:557–566. doi: 10.1590/S0101-20612009000300017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinhardt J, Beychok S. Interaction of proteins with hydrogen ions and other small ions and molecules. The Proteins: Composition, Structure and Function. 1964;2:139–304. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kristinsson HG, Rasco BA. Kinetics of the hydrolysis of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) muscle proteins by alkaline proteases and a visceral serine protease mixture. Process Biochem. 2000;36:131–139. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(00)00195-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pastore GM, Bicas JL, Junior MRM. Biotecnologia de alimentos. São Paulo: Atheneu; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tavernari FC, Albino LFT, et al. Farelo de girassol: composição e utilização na alimentação de frangos de corte. Rev Ele Nutr. 2008;5:638–647. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rostagno HS, Albino LT et al (2011) Brazilian tables for poultry and swine: composition of feedstuffs and nutritional requirements. UFV, DZO: Viçosa

- 28.Zarkadas CG, Yu Z, Voldeng HD, Hope HJ, Minero-Amador A, Rochemont JA. Comparison of the protein-bound and free amino acid contents of two northern adapted soybean cultivars. J Agric Food Chem. 1994;42:21–33. doi: 10.1021/jf00037a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshizawa K. The formation of higher alcohols in the fermentation of amino acids by yeast: the formation of isobutanol from α-acetolactic acid by washed yeast cells. Agric Biol Chem. 1964;28:279–285. doi: 10.1080/00021369.1964.10858244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X, Nielsen KF, Borodina I, Kielland-Brandt MC, Karhumaa K. Increased isobutanol production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by overexpression of genes in valine metabolism. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2011;4:21. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villanueva A, Vioque J, Sánchez-Vioque R, Clemente A, Pedroche J, Bautista J, Millán F. Peptide characteristics of sunflower protein hydrolysates. J Amer Oil Chem Soc. 1999;76:1455–1460. doi: 10.1007/s11746-999-0184-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ordonez C, Benitez C, Gonzalez JL. Amino acid production from a sunflower wholemeal protein concentrate. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:4749–4754. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taheri A, Kenari AA et al (2011) Poultry by-products and enzymatic hydrolysis: optimization by response surface methodology using Alcalase® 2.4 L. Inter J Food Eng 7(5). 10.2202/1556-3758.1969

- 34.Carrão-Panizzi MC, Mandarino JMG (1994) Girassol: derivados protéicos. Embrapa Soja-Documentos (INFOTECA-E)

- 35.Perry JR, Basrai MA, Steiner HY, Naider F, Becker JM. Isolation and characterization of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae peptide transport gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:104–115. doi: 10.1128/MCB.14.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huo YX, Cho KM, Rivera JGL, Monte E, Shen CR, Yan Y, Liao JC. Conversion of proteins into biofuels by engineering nitrogen flux. Nat Biotech. 2011;29:346–351. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gutierrez LE. Produção de álcoois superiores por linhagens de Saccharomyces durante a fermentação alcoólica. Sci Agric. 1993;50:464–472. doi: 10.1590/S0103-90161993000300021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sentheshanmuganathan S, Elsden SR. The mechanism of the formation of tyrosol by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem J. 1958;69:210–218. doi: 10.1042/bj0690210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serp D, von Stockar U, Marison IW. Enhancement of 2-phenylethanol productivity by Saccharomyces cerevisiae in two-phase fed-batch fermentations using solvent immobilization. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2003;82:103–110. doi: 10.1002/bit.10545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Äyrápáá T. Biosynthetic formation of higher alcohols by yeast. Dependence on the nitrogenous nutrient level of the medium JI. Brewing. 1971;77:266–276. doi: 10.1002/j.2050-0416.1971.tb06945.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atsumi S, Cann AF, Connor MR, Shen CR, Smith KM, Brynildsen MP, Chou KJY, Hanai T, Liao JC. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for 1-butanol production. Metab Eng. 2008;10:305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steen EJ, Chan R, Prasad N, Myers S, Petzold CJ, Redding A, Ouellet M, Keasling JD. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the production of n-butanol. Microb Cell Factories. 2008;7:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-7-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 280 kb)