Abstract

Introduction

Current diabetes quality measures are agnostic to patient clinical complexity and type of treatment required to achieve it. Our objective was to introduce a patient-centered indicator of appropriate diabetes therapy indicator (ADTI), designed for patients with type 2 diabetes, which is based on hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) but is also contextualized by patient complexity and treatment intensity.

Research design and methods

A draft indicator was iteratively refined by a multidisciplinary Delphi panel using existing quality measures, guidelines, and published literature. ADTI performance was then assessed using OptumLabs Data Warehouse data for 2015. Included adults (n=206 279) with type 2 diabetes were categorized as clinically complex based on comorbidities, then categorized as treated appropriately, overtreated, or undertreated based on a matrix of clinical complexity, HbA1c level, and medications used. Associations between ADTI and emergency department/hospital visits for hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia were assessed by calculating event rates for each treatment intensity subset.

Results

Overall, 7.4% of patients with type 2 diabetes were overtreated and 21.1% were undertreated. Patients with high complexity were more likely to be overtreated (OR 5.60, 95% CI 5.37 to 5.83) and less likely to be undertreated (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.68) than patients with low complexity. Overtreated patients had higher rates of hypoglycemia than appropriately treated patients (22.0 vs 6.2 per 1000 people/year), whereas undertreated patients had higher rates of hyperglycemia (8.4 vs 1.9 per 1000 people/year).

Conclusions

The ADTI may facilitate timely, patient-centered treatment intensification/deintensification with the goal of achieving safer evidence-based care.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, type 2, quality of health care, health services research, insurance claim review

Significance of this study.

What is already known about this subject?

To align quality measurement with established scientific evidence and to individualize hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) targets and glucose-lowering regimens to balance the anticipated benefits of lowering HbA1c with potential harms, we developed the appropriate diabetes therapy indicator (ADTI), which seeks to identify patients with type 2 diabetes who may be overtreated or undertreated based on their HbA1c level, glucose-lowering medications used, and clinical complexity.

What are the new findings?

Both overtreatment and undertreatment of commercially insured and Medicare Advantage beneficiaries in the USA were common, with patients with high clinical complexity significantly more likely to be overtreated (OR 5.60) but less likely to be undertreated (OR 0.65) compared with patients with low clinical complexity.

Patients classified as overtreated by the ADTI had higher rates of severe hypoglycemia requiring emergency department or hospital care, while patients classified as undertreated had higher rates of severe hyperglycemia.

How might these results change the focus of research or clinical practice?

The ADTI may be used by clinical practices and individual clinicians to facilitate timely, patient-centered treatment intensification/deintensification with the goal of achieving safer evidence-based care.

Introduction

Lowering blood glucose levels in patients with diabetes can reduce the risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications but may necessitate polypharmacy and lead to adverse events, including hypoglycemia. Patients who are clinically complex and/or require multiple glucose-lowering agents or insulin to attain desired glycemic targets are most likely to experience hypoglycemia.1 Clinical practice guidelines advise individualizing hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) targets and glucose-lowering regimens to balance the anticipated benefits of lowering HbA1c with the potential harms.2–7 However, current diabetes quality measures used for population health management, public reporting, and pay-for-performance reimbursement are not designed to evaluate this balance. Instead, they consist of dichotomous thresholds of glycemic control, most often <8%, uniformly applied to nearly all adults aged 18–75 years,8 irrespective of the patient’s clinical complexity, risk for hypoglycemia, and required intensity of glucose-lowering therapy. This approach is not aligned with the goal of delivering high-quality, patient-centered care, and may contribute to the risk/treatment paradox seen in contemporary clinical practice, whereby younger, healthier patients commonly undertreated while older, more clinically complex patients are overtreated.9 As such, there is an urgent need to align the anticipated benefits and harms of treatment with the therapeutic goals pursued by a given patient.

Uniform, dichotomous measures of diabetes control are ill suited to evaluate the individual-level quality and safety of diabetes care. They may miss undertreatment of younger, healthier adults with diabetes who may be harmed by long-term exposure to hyperglycemia (including HbA1c 7%–8%).10 They may also miss overtreatment of older, clinically complex, or already intensively treated patients, for whom achieving HbA1c <8% may not be possible without substantial hypoglycemia risk and may not yield meaningful improvements in health outcomes. Recognizing the need to support individualized glycemic targets, Pogach and colleagues introduced an out-of-range glycemic control measure for older adults with diabetes (aged ≥65 years) who have serious comorbid health conditions.11 While this measure addresses concerns about overtreatment of older and clinically complex adults, it does not tackle the potential overtreatment of younger clinically complex adults,12 nor does it address the potential undertreatment of older or younger adults.

We therefore engaged a multidisciplinary team of clinicians, researchers, and health plan representatives, and partnered with AARP and OptumLabs in collaboration with the National Quality Forum (NQF) Measure Incubator, to develop an appropriate diabetes therapy indicator (ADTI) for adults with diabetes across a range of clinical complexity. Herein, we describe the application of the ADTI to administrative claims data within OptumLabs Data Warehouse (OLDW) to simulate its use in clinical practice. To test the validity of the proposed approach, we then examine the association between treatment appropriateness, as calculated by the ADTI, and rates of emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations for hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia among adults with type 2 diabetes in OLDW.

Subjects, materials, and methods

Study design

A candidate indicator was proposed by the research team on the basis of currently available quality measures,8 clinical practice guidelines,2–7 13 and published literature. This definition was iteratively refined with input from a modified Delphi panel which comprised 12 multidisciplinary non-patient stakeholders. Patient perspective was provided by the Mayo Clinic Diabetes Patient Advisory Group. The final indicator definition was evaluated using administrative claims and laboratory data from OLDW. Because this study involved statistically deidentified data, it was exempt from Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board review.

Modified Delphi panel deliberations

We convened a 12-member modified Delphi panel, selected by call for nominations to OptumLabs partner institutions and the NQF Measure Incubator network, to develop and refine the proposed measure of appropriate diabetes therapy. Selected members included clinicians (endocrinology, primary care, geriatrics), pharmacists, nurses, researchers, and representatives of public and private health plans. Deliberations on the measure consisted of four 90 min meetings held over teleconference. After each conversation, participants provided additional feedback on the measure including recommendations for additional testing (to inform the measure) and further refinement. The final measure definition was unanimously approved by the panel.

Patient perspective

The study team presented a draft of the ADTI to members of the Diabetes Patient Advisory Group and sought feedback on the general approach, specific components of the measure definition, and implementation strategies. The advisory group comprised approximately 10 community members with diabetes and their caregivers. This long-standing group meets with researchers on a monthly basis to provide feedback on research proposals, participant recruitment materials, surveys, and all areas of proposed and existing research grounded in their personal, practical experiences in living with diabetes.

Indicator definition

The ADTI indicator aims to identify glucose-lowering regimens that may not be appropriate for an individual patient and which may need to be re-evaluated in conversation with the patient. Patients identified as potentially overtreated or undertreated may benefit from clinical reassessment to determine whether and what actions need to be taken to better align their management with best available evidence and patients’ goals for their care (online supplemental figure 1). ADTI therefore incorporates three factors: the patient’s clinical complexity, achieved HbA1c level, and current treatment intensity.

bmjdrc-2020-001878supp001.pdf (774.1KB, pdf)

Clinical complexity

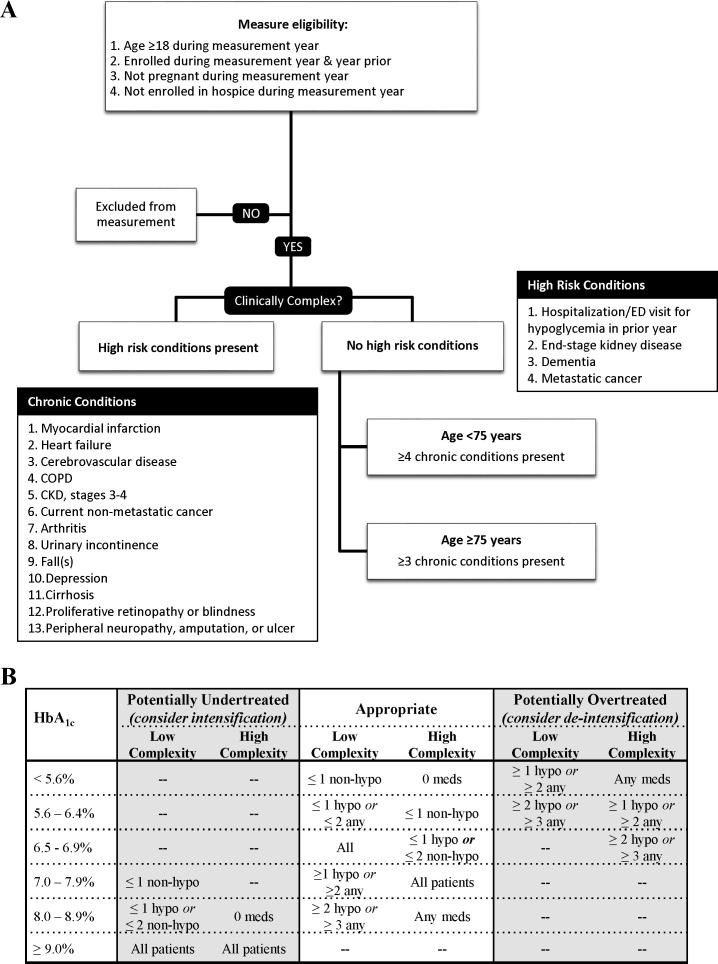

The designation of clinical complexity centered on the risk of severe hypoglycemia, the probability of serious harm ensuing from a hypoglycemic event, and overall disease burden (figure 1). We considered patients as clinically complex if they were 18–74 years old and had ≥4 chronic conditions, or were ≥75 years old and had ≥3 chronic conditions.

Figure 1.

Consensus definition for the appropriate diabetes therapy indicator. (A) Specification of clinical complexity on the basis of patient age during the measurement year and comorbidities ascertained during the year prior to the measurement year. (B) Diabetes treatment regimens that may be suggestive of undertreatment, overtreatment, and appropriate treatment as a function of HbA1c and patient clinical complexity. Medications are classified as increasing the risk of hypoglycemia (sulfonylurea, basal insulin, bolus insulin; ‘hypo-prone’) or not (metformin, sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibitors, thiazolidinediones, α-glucosidase inhibitors, meglitinides, amylin analog). Patients treated with multiple daily insulin injections or insulin pump therapy are considered to receive two hypoglycemia-prone medications. CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c.

Candidate conditions were those specified by the American Diabetes Association,5 6 American Geriatrics Society,13 and/or US Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense2 diabetes management guidelines: dementia, end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), stages 3–4 of chronic kidney disease, advanced liver disease (cirrhosis), heart failure, myocardial infarction, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer), urinary incontinence, falls, arthritis, proliferative retinopathy or blindness, and peripheral neuropathy or amputation or ulcer (online supplemental figure 2). Hypertension was excluded from among the complexity-defining conditions based on Delphi panel input because it is common, does not independently increase risk of hypoglycemia,1 and does not signal diminished life expectancy.14 History of hypoglycemia requiring ED or hospital care in the prior year was added, per guideline specifications suggesting more relaxed treatment targets in this context6 and in recognition of the high risk for hypoglycemia recurrence.1 Dementia, ESKD, and metastatic cancer were weighted more strongly than the other conditions, consistent with the guidelines,2 5 6 13 as they signify short life expectancy, high disease burden, and high risk of hypoglycemia.1 We did not include a measure of life expectancy, as it cannot be reliably ascertained using claims data and thereby is not practical for efficient and generalizable indicator use. Age was considered indirectly, in an effort to balance the known association between advanced age and hypoglycemia (specifically, age ≥75 is a risk factor for hypoglycemia independent of comorbidity)1 and as a marker for remaining life expectancy, with the appreciation that otherwise healthy older adults have sufficient life expectancy to benefit from moderate glycemic control.15

Treatment intensity

Treatment intensity was defined for each HbA1c range by clinical complexity as a function of the number and type (prone to hypoglycemia vs not) of medication use (figure 1). The last HbA1c of 2015 was used, consistent with established measure methodology.8 Diabetes medications were identified from outpatient pharmacy claims during 100 days preceding the HbA1c measurement and classified as at risk for hypoglycemia (insulin, sulfonylurea) versus not (all others; eg, metformin, sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, thiazolidinediones, α-glucosidase inhibitors, meglitinides, amylin analog), consistent with earlier overtreatment measures.11

ADTI evaluation

Data source

The ADTI was assessed using data from OLDW between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2015. OLDW comprised deidentified medical and pharmacy claims, laboratory results, and enrollment records for commercially insured and Medicare Advantage enrollees.16 Included plans are employer-sponsored health plans available to working individuals and their families and Medicare Advantage health plans, which are private sector alternatives to traditional government-sponsored Medicare Part A/B plans available to retirees. The database contains longitudinal health information on enrollees, representing a diverse mixture of ages, ethnicities, and geographic regions across the USA.

Study population

We identified all adult enrollees (≥18 years) with type 2 diabetes who had medical and pharmacy health plan coverage from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2015, and had an available HbA1c result in 2015. Patients who were pregnant or enrolled in hospice during the measurement year (2015) were excluded, per measure specifications (see online supplemental table 1 for relevant codes). The diagnosis of diabetes was established using Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set criteria applied to 2013 and 2014 claims. We excluded patients with type 1 diabetes based on the following criteria: (1) plurality of diabetes Evaluation & Management (E&M) diagnosis codes for type 1 diabetes and fill(s) for bolus insulin, or (2) equal number of type 1 and type 2 diabetes E&M codes and fill(s) for bolus insulin and no fills for sulfonylureas. This classification scheme is consistent with prior literature.9 17 18

Outcomes

The primary outcome was appropriateness of diabetes therapy calculated for the 2015 measurement year. Sensitivity analyses examined ADTI performance among patients aged 18–75 years (consistent with current measures) and >75 years. We compared ADTI results for our population to existing National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) glycemic control indicator,8 which applies a uniform threshold of HbA1c <8.0% vs ≥8% irrespective of the treatment regimen or patient complexity, and is limited to patients aged 18–75 years. Secondary analyses examined (1) baseline patient characteristics associated with increased odds of undertreatment and overtreatment, as compared with appropriate treatment; (2) incidence of ED visits or hospitalizations for hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia in the different appropriateness subgroups; and (3) variation in the proportion of patients treated appropriately among providers of different specialties (internal medicine, family medicine, endocrinology).

Independent variables

Patient age, sex, annual household income, US region, health plan, and race/ethnicity were identified from OLDW enrollment files. Variables were selected on the basis of their demonstrated association with the choice of glucose-lowering therapy and intensity of glycemic control.9 19 They were used to assess for heterogeneity in meeting the ADTI and factors associated with receipt of appropriate care, but were not included in the ADTI itself.

Patient attribution

Eligible providers were physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants in either primary care (internal medicine, family medicine) or endocrinology. Patients were attributed to eligible providers based on the plurality of E&M office visits in 2014–2015. In the event of a tie, patients were attributed to the eligible provider with the plurality of visits in 2015. In the event of persistent tie, patients were attributed to the eligible provider with the last E&M office visit in 2015.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the overall frequencies (percentages) and means (SD) for patient characteristics, overall and stratified by clinical complexity. ADTI performance was calculated as the proportion of patients treated appropriately, undertreated, or overtreated.

A multinomial logistic regression model (reference: appropriate therapy) was used to separately assess the association of undertreatment and overtreatment with baseline patient characteristics, clinical complexity, and attributed provider. Results are reported as ORs and 95% CIs.

Variation in the proportion of patients treated appropriately for individual providers was calculated for providers with ≥25 attributed patients. Differences across specialties (internal medicine, family medicine, and endocrinology) were tested using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Rates of ED visits and hospitalizations with the primary diagnoses of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia in 2015 were calculated for each appropriateness group, reported as the number of events per 1000 enrollees per year.

All analyses were conducted using SAS software V.9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Study population

The study population comprised 206 279 adults, of whom 24 604 (11.9%) were clinically complex (online supplemental table 2). Mean age was 65.5 years (SD 12.1), 49.6% were female, and 58.9% were White. The distribution of qualifying conditions among patients of high clinical complexity is shown in online supplemental table 3; 3557 (14.5%) patients met more than one criterion for clinical complexity. Most were attributed to a primary care provider (47.5% to family medicine, 43.5% to internal medicine); 4.6% were attributed to an endocrinologist and 4.4% could not be attributed.

ADTI assessment

Overall, 71.5% were treated appropriately, 21.1% were potentially undertreated, and 7.4% were potentially overtreated (table 1). Patient characteristics by treatment designation are shown in online supplemental table 4. The proportion of undertreated was higher among patients of low complexity (22.6% vs 10.3%), while the proportion of overtreated was higher among those with high complexity (23.4% vs 5.3%). Similarly, the proportion of overtreated was highest among patients ≥75 years (9.5%), while the proportion of undertreated was highest among patients 18–44 years (32.5%).

Table 1.

Appropriateness of diabetes therapy results in OptumLabs Data Warehouse. Overall results are calculated per low-complexity and high-complexity subgroups and for the whole study population

| hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) | Potentially undertreated (consider intensification) | Appropriate | Potentially overtreated (consider deintensification) | |||

| Low complexity (%) | High complexity (%) | Low complexity (%) | High complexity (%) | Low complexity (%) | High complexity (%) | |

| <5.6% | – | – | 3997 (54.2) | 636 (8.6) | 1934 (26.2) | 801 (10.9) |

| 5.6%–6.4% | – | – | 47 139 (75.1) | 4628 (7.4) | 7616 (12.1) | 3411 (5.4) |

| 6.5%–6.9% | – | – | 36 634 (89.1) | 2948 (7.2) | – | 1551 (3.8) |

| 7.0%–7.9% | 11 495 (23.7) | – | 31 577 (65.0) | 5488 (11.3) | – | – |

| 8.0%–8.9% | 7337 (33.7) | 72 (0.3) | 11 771 (54.0) | 2616 (12.0) | – | – |

| ≥9.0% | 22 175 (90.0) | 2453 (10.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Overall | 41 007 (22.6) | 2525 (10.3) | 131 118 (72.2) | 16 316 (66.3) | 9550 (5.3) | 5763 (23.4) |

| 43 532 (21.1) | 147 434 (71.5) | 15 313 (7.4) | ||||

We also compared ADTI results for our population to the NCQA glycemic control indicator8 (online supplemental table 5). Overall, 7.2% of patients with HbA1c <8.0% were classified as undertreated and 9.6% were classified as overtreated by the ADTI, whereas all would be considered ‘appropriately’ treated by the NCQA definition. Of the 46 424 patients with HbA1c ≥8.0%, who would all be considered as ‘undertreated’ by the NCQA definition, 31.0% were reclassified as appropriately treated by the ADTI. Restricting the study population to patients 75 years and younger, as in the NCQA measure, did not substantially alter the results. Nearly 86% of patients older than 75 years had achieved HbA1c <8.0% and 11.3% of them were classified as overtreated, while 58.9% of patients with HbA1c ≥8.0% were classified as undertreated.

There was significant variation in the proportion of patients receiving appropriate therapy by attributed provider specialty (online supplemental table 6). The median proportion of patients receiving appropriate care was highest among internal medicine providers (77.0%) and lowest among endocrinologists (71.5%); p=0.002. Internal medicine providers had the lowest number overtreated (6.6%), family medicine providers had the highest number undertreated (18.5%), while endocrinology had the highest number overtreated (11.0%) and lowest number undertreated (13.6%).

Factors associated with ADTI performance

The strongest predictors of whether a patient received appropriate glucose-lowering therapy or was undertreated/overtreated were clinical complexity and age (table 2). Odds of overtreatment of patients with high complexity, as compared with patients of low complexity, was 5.60 (95% CI 5.37 to 5.83), while their odds of undertreatment was 0.65 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.68). The odds of both undertreatment and overtreatment declined with patient age, such that patients ≥75 years had an OR 0.40 (95% CI 0.38 to 0.42) of being undertreated and an OR 0.45 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.50) of being overtreated compared with patients 18–44 years. We also found that Black patients (OR 1.26; 95% CI 1.23 to 1.30) and Hispanic patients (OR 1.25; 95% CI 1.21 to 1.29) were both more likely to be undertreated compared with White patients. Women were less likely than men to be both undertreated (OR 0.85; 95% CI 0.83 to 0.87) and overtreated (OR 0.90; 95% CI 0.87 to 0.93). Patient income was inversely associated with odds of undertreatment (OR 0.75; 95% CI 0.73 to 0.78 for annual household income ≥$100 000 vs <$40 000) and had no association with odds of overtreatment. Having Medicare Advantage health coverage, as compared with commercial, was also associated with decreased odds of undertreatment (OR 0.82; 95% CI 0.79 to 0.85) and had no association with overtreatment. Patients attributed to endocrinologists were less likely to be undertreated than those attributed to internal medicine providers (OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.84 to 0.93), and significantly more likely to be overtreated (OR 1.57; 95% CI 1.45 to 1.69).

Table 2.

Predictors of patient undertreatment and overtreatment

| Variable | Undertreatment | Overtreatment | ||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Clinical complexity | ||||

| Low | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| High | 0.65 (0.62 to 0.68) | <0.001 | 5.60 (5.37 to 5.83) | <0.001 |

| Age group (years) | ||||

| 18–44 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 45–64 | 0.78 (0.75 to 0.82) | <0.001 | 0.63 (0.58 to 0.68) | <0.001 |

| 65–74 | 0.53 (0.50 to 0.56) | <0.001 | 0.53 (0.49 to 0.58) | <0.001 |

| ≥75 | 0.40 (0.38 to 0.42) | <0.001 | 0.45 (0.41 to 0.50) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Female | 0.85 (0.83 to 0.87) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.87 to 0.93) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Black | 1.26 (1.23 to 1.30) | <0.001 | 1.02 (0.97 to 1.07) | 0.52 |

| Hispanic | 1.25 (1.21 to 1.29) | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.81 to 0.90) | <0.001 |

| Asian | 0.95 (0.90 to 0.99) | 0.03 | 0.70 (0.64 to 0.76) | <0.001 |

| Unknown/missing | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.05) | 0.54 | 0.84 (0.74 to 0.94) | 0.003 |

| US region | ||||

| Midwest | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Northeast | 1.11 (1.07 to 1.15) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.75 to 0.84) | <0.001 |

| South | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.02) | 0.68 | 0.84 (0.80 to 0.88) | <0.001 |

| West | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.05) | 0.73 | 0.85 (0.80 to 0.92) | <0.001 |

| Annual household income | ||||

| <$40 000 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| $40 000–$49 999 | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.01) | 0.13 | 0.97 (0.91 to 1.04) | 0.42 |

| $50 000–$59 999 | 0.96 (0.92 to 1.00) | 0.05 | 0.91 (0.85 to 0.97) | 0.004 |

| $60 000–$74 999 | 0.92 (0.88 to 0.95) | <0.001 | 0.98 (0.92 to 1.04) | 0.49 |

| $75 000–$99 999 | 0.89 (0.86 to 0.92) | <0.001 | 0.98 (0.92 to 1.03) | 0.41 |

| ≥$100 000 | 0.75 (0.73 to 0.78) | <0.001 | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.10) | 0.13 |

| Unknown | 0.99 (0.93 to 1.05) | 0.68 | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.19) | 0.07 |

| Attributed provider | ||||

| Internal medicine | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Family medicine | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.09) | <0.001 | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.05) | 0.67 |

| Endocrinology | 0.88 (0.84 to 0.93) | <0.001 | 1.57 (1.45 to 1.69) | <0.001 |

| Unattributed | 1.10 (1.04 to 1.16) | <0.001 | 1.07 (0.99 to 1.17) | 0.10 |

| Health plan | ||||

| Commercial | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Medicare Advantage | 0.82 (0.79 to 0.85) | <0.001 | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.11) | 0.14 |

Odds of potential undertreatment and overtreatment were calculated using a multinomial logistic regression model with the reference set to receipt of appropriate therapy.

Association between treatment intensity and severe dysglycemia

Overtreated patients had higher rates of hypoglycemia-related ED visits/hospitalizations (22.0 events/1000 enrollees/year) than appropriately treated patients (6.2 events/1000 enrollees/year) (table 3). In contrast, undertreated patients had higher rates of hyperglycemia-related ED visits/hospitalizations (8.4 events/1000 enrollees/year) than appropriately treated patients (1.9 events/1000 enrollees/year).

Table 3.

Rates of severe hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia as a function of ADTI performance

| Undertreated (n=43 532) | Appropriately treated (n=147 434) | Overtreated (n=15 313) | P value | |

| Hypoglycemia | ||||

| Patients with event, n (%) | 410 (0.9) | 813 (0.6) | 296 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| Event rate per 1000 enrollees per year | 10.66 | 6.15 | 22.01 | <0.001 |

| Hyperglycemia | ||||

| Patients with event, n (%) | 311 (0.7) | 251 (0.2) | 53 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| Event rate per 1000 enrollees per year | 8.41 | 1.87 | 3.66 | <0.001 |

The proportion of patients with at least one event, and the total number of events per 1000 enrollees per year, were calculated among undertreated, appropriately treated, and overtreated patients as defined by the ADTI.

ADTI, appropriate diabetes therapy indicator.

Discussion

In an effort to promote high-quality, evidence-based, and safe diabetes management at the individual and population levels, we proposed and evaluated a new quality indicator for the appropriateness of glucose-lowering therapy among patients with type 2 diabetes. The ADTI balances the benefits of glucose-lowering therapy with the potential harms of hypoglycemia and treatment burden (eg, polypharmacy). When we applied the ADTI to a real-world population of 206 279 adults with type 2 diabetes, we found that 21.1% are potentially undertreated and 7.4% are potentially overtreated. As may be expected, overtreatment was far more common among clinically complex patients, while undertreatment was more common among patients with low complexity. These findings underscore the need for balanced quality indicators that can identify both excessive and inadequate treatment regimens. Using this information, clinicians can engage patients in conversation about their glucose-lowering therapy with the ultimate goal of aligning treatment regimens with patients’ clinical contexts as well as goals and preferences for care.

In the era of population health management, patients are often identified for surveillance or intervention only when they meet a particular metric (eg, high HbA1c) or experience an adverse health outcome (eg, hospitalization). The ADTI can help clinicians identify patients who may be either undertreated (the focus of currently existing quality measures, although in a less nuanced way) or overtreated (which has not been done to date). This approach also addresses other concerns raised about quality measurement,20 whether used for pay-for-performance/public reporting or to facilitate better care through quality improvement. ADTI is not a one-size-fits-all metric; instead, it promotes shared decision-making and personalization of glucose-lowering therapy. By inherently risk adjusting the recommended HbA1c level and the intensity of the glucose-lowering treatment regimen, ADTI encourages therapy that is more likely to be aligned with patient’s clinical context. It also recognizes the effort patients and clinicians make to control hyperglycemia even when HbA1c does not fall below 8%, while reinforcing the benefits of tighter glycemic control for less complex patients. Indeed, 31% of patients with HbA1c ≥8.0% would still be considered appropriately treated by the ADTI, either because of their underlying clinical complexity (wherein more intensive treatment may not be evidence based) or the complexity of their current treatment regimen (wherein more intensive treatment may be unsafe). Conversely, 7.2% of patients with HbA1c <8.0% were still classified as undertreated, reinforcing the benefits of more intensive glycemic control for otherwise healthy patients with long life expectancy. Finally, ADTI identified the 9.6% of patients with HbA1c ≥8.0% who were still overtreated and may benefit from treatment deintensification. By considering the number and type of glucose-lowering medications used to lower HbA1c, the ADTI may provide actionable guidance to patients and providers, and thereby overcome the therapeutic inertia of either overtreatment or undertreatment.

We found that clinically complex patients were 5.6 times more likely to be overtreated (rather than appropriately treated) than patients with low clinical complexity. High rates of potential overtreatment have been observed in a variety of settings and populations,9 21–27 and overtreated patients’ treatment regimens are rarely deintensified.23 24 28 While diabetes overtreatment measures have been proposed previously,11 29 30 they have not been widely incorporated into practice. This may be driven, in part, by clinician, health system, and patient-driven concerns about treatment deintensification.31 32 However, there is increasing recognition of the morbidity33–39 and mortality33 35–37 39–42 incurred by hypoglycemia, with concerted efforts by professional societies and regulatory bodies seeking to reduce these events. Proactive identification of at-risk overtreated patients would be the necessary first step.

Conversely, patients with low clinical complexity were 35% more likely to be undertreated than patients with high complexity. This is consistent with prior studies demonstrating high rates of poor glycemic control among younger patients with diabetes.9 43 44 Even though our study population comprised commercially insured individuals, younger patients may be more likely to be underinsured or have high deductible health plans, contributing to lower use of glucose-lowering medications,45 worse glycemic control, and poor health outcomes.46 The important role of cost and affordability of diabetes management is underscored by the inverse relationship between annual household income and odds of undertreatment, with higher income individuals significantly less likely to be undertreated. Medicare Advantage beneficiaries were also significantly less likely to be undertreated. This may reflect better access to care by retired Medicare Advantage beneficiaries as compared with working-age commercially insured patients, as well as the greater reliance on hypoglycemia-prone drugs (and lower rates of use of newer, non-hypoglycemia-prone drugs)19 47 that make it less likely for a patient to be classified as undertreated. Such undertreatment of patients who are likely to derive benefit from glycemic control reinforces the importance of continued focus on improving access to diabetes care and affordability of glucose-lowering therapies.

Black and Hispanic patients were significantly more likely to be undertreated than White patients. These disparities in diabetes management may be driven by the clinician’s failure to intensify therapy, the patient’s inability to access or afford recommended treatments, and greater burden of social determinants of health. Racial/ethnic minorities have worse diabetes-related health outcomes and greater risk of mortality compared with White patients,48 49 which may stem from gaps in care quality revealed by application of the ADTI.

Overtreatment and undertreatment, as identified by the ADTI, strongly correlated with subsequent risks of experiencing hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia requiring ED or hospital-level care. The rates of ED/hospital visits for hypoglycemia were 22.0 per 1000 people/year among the overtreated compared with 6.2 per 1000 people/year among those appropriately treated. This is important, particularly considering that the vast majority of severe hypoglycemic events do not culminate in an ED/hospital visit.50–52 Conversely, the rates of ED/hospital visits for hyperglycemia were 8.4 per 1000 people/year among the undertreated compared with 1.9 per 1000 people/year among those appropriately treated. Our findings suggest the potential preventability of these events with appropriate glucose management, particularly for the most vulnerable populations.

Our study has several important limitations. HbA1c is a surrogate measure of glycemic control and does not capture the totality of the diabetes care experience.53 While measures such as time in target range more accurately reflect real-time glycemia,54 this approach remains impractical for population-level performance measurement particularly for patients with type 2 diabetes, most of whom do not use (and do not need to use, depending on their treatment regimen) continuous glucose-monitoring technologies. The examined comorbidities do not reflect the full range of biological, sociological, economic, environmental, and behavioral factors that affect a patient’s complexity, contribute to burden of treatment and disease, and impact capacity of self-management and care. While we focused specifically on comorbid conditions identified by the clinical guidelines2 5 6 13 and associated with increased risk for hypoglycemia,1 other potentially pertinent comorbidities and non-clinical risk factors were not captured. We did not account for patient adherence to treatment or for their personal preferences of goals for care. Nevertheless, the ADTI can identify potentially inappropriate care in order to stimulate more nuanced and evidence-based clinical discussions about the goals and processes of diabetes care.

Finally, while the ADTI was evaluated among patients with private insurance and the evaluation results are likely to differ in other populations that may have greater barriers to care and affordability of brand name non-hypoglycemia-prone medications, the underlying principle of appropriate therapy is pertinent to all people with diabetes.

The goal of the ADTI is to ensure that all adults with diabetes receive high-quality, evidence-based, timely, and equitable care. It does so by taking into consideration the HbA1c level and each patient’s clinical complexity and treatment burden. This approach can be readily implemented across a range of clinical settings and healthcare delivery systems, as the required components are already used for quality measurement and reporting, including administrative data (diagnoses), HbA1c results, and patient age. Prospective evaluation of the impact of this indicator on diabetes care quality, patient health outcomes, and administrative burden, as compared with existing dichotomous measures, is necessary prior to its broad dissemination.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all the members of the expert Delphi panel for their time, insights, and commitment to this work. Members of the group were Geraldine Doetzer, JD (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services), Neda Laiteerapong, MD, MS (University of Chicago), Chris Lamer, PharmD, MHS, BCPS, CDE (USPHS Indian Health Service), Benjamin Landsman, MHA (Polyclinic), John Matulis, DO, MPH (Mayo Clinic), Khalilah McCants, DNP, MSN, BSN, BA, RN-BC (UnitedHealth Group), Medha Munshi, MD, MS (Harvard Medical School), Scott Ode, PhD (Mathematica), Christie Teigland, PhD (Avalere Health), Kathleen Vest, PharmD (Midwestern University Chicago College of Pharmacy), Kristina Yu-Isenberg, BS, MPH, PhD (Intarcia Therapeutics), and Evonne Waters, DrBA, MPH, BSN (TWC Research Group). We also thank Stephan Dunning and Albert Feldman of OptumLabs for their assistance in conducting the Delphi panel. Finally, we are deeply grateful to the members of the Mayo Clinic Diabetes Patient Advisory Group for their feedback on the proposed measure goals/objectives, definition, and implementation potential.

Footnotes

Twitter: @RozalinaMD

Presented at: Preliminary data for this publication were presented as poster presentations at the American Diabetes Association 79th Scientific Sessions in San Francisco, California (7–11 June 2019).

Contributors: RGM and NDS are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. RGM designed the study, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. KJL contributed to the discussion and reviewed/edited the manuscript. HKVH analyzed the data and reviewed/edited the manuscript. NDS supervised the study design and data interpretation, contributed to the discussion, and reviewed/edited the manuscript.

Funding: This effort was funded by an AARP Quality Measure Innovation Grant through a collaboration with OptumLabs and the NQF Measure Incubator (RGM) and the National Institute of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant number K23DK114497) (RGM).

Disclaimer: Study contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

Competing interests: RGM also receives support from the Mayo Clinic Center for Health Equity and Community Engagement Research. In the past 36 months, KJL also received support from the National Institute on Aging and the American Federation of Aging Research through the Paul Beeson Career Development Award (K23AG048359), the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG021342), and from CMS to develop and maintain publicly reported quality measures. In the past 36 months, NDS has received research support through Mayo Clinic from the Food and Drug Administration to establish Yale-Mayo Clinic Center for Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation (CERSI) program (U01FD005938); the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Innovation under the Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative (TCPI); the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1U19HS024075; R01HS025164; R01HS025402; R03HS025517); the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R56HL130496; R01HL131535); the National Science Foundation; and the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) to develop a Clinical Data Research Network (LHSNet).

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. This study was conducted using deidentified claims data from OptumLabs Data Warehouse.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.McCoy RG, Lipska KJ, Van Houten HK, et al. . Association of cumulative multimorbidity, glycemic control, and medication use with Hypoglycemia-Related emergency department visits and hospitalizations among adults with diabetes. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e1919099–e99. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conlin PR, Colburn J, Aron D, et al. . Synopsis of the 2017 U.S. department of Veterans Affairs/U.S. Department of defense clinical practice guideline: management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:655–63. 10.7326/M17-1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. . Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American college of endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm - 2019 executive summary. Endocr Pract 2019;25:69–100. 10.4158/CS-2018-0535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for health and care excellence National Institute for health and care excellence pathways: managing blood glucose in Aults with type 2 diabetes, 2019. Available: https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/type-2-diabetes-in-adults [Accessed 23 Apr 2019].

- 5.American Diabetes Association 12. Older Adults: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care 2020;43:S152–62. 10.2337/dc20-S012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Diabetes Association 6. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care 2020;43:S66–76. 10.2337/dc20-S006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LeRoith D, Biessels GJ, Braithwaite SS, et al. . Treatment of diabetes in older adults: an endocrine Society* clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;104:1520–74. 10.1210/jc.2019-00198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Committee for Quality Assurance Comprehensive Diabetes Care: Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) Control (<8.0%). National Quality Forum (NQF)-endorsed measure #0575. Measure steward. Available: http://www.qualityforum.org/QPS/MeasureDetails.aspx?standardID=944&print=0&entityTypeID=1 [Accessed 21 Feb 2020].

- 9.McCoy RG, Lipska KJ, Van Houten HK, et al. . Paradox of glycemic management: multimorbidity, glycemic control, and high-risk medication use among adults with diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2020;8:e001007. 10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-001007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tancredi M, Rosengren A, Svensson A-M, et al. . Excess mortality among persons with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1720–32. 10.1056/NEJMoa1504347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pogach L, Tseng C-L, Soroka O, et al. . A proposal for an Out-of-Range glycemic population health safety measure for older adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2017;40:518–25. 10.2337/dc16-0953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCoy RG, Lipska KJ, Yao X, et al. . Intensive treatment and severe hypoglycemia among adults with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:969–78. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, et al. . Diabetes in older adults: a consensus report. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:2342–56. 10.1111/jgs.12035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee TA, Shields AE, Vogeli C, et al. . Mortality rate in veterans with multiple chronic conditions. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22(Suppl 3):403–7. 10.1007/s11606-007-0277-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leal J, Gray AM, Clarke PM. Development of life-expectancy tables for people with type 2 diabetes. Eur Heart J 2009;30:834–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace PJ, Shah ND, Dennen T, et al. . Optum Labs: building a novel node in the learning health care system. Health Aff 2014;33:1187–94. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klompas M, Eggleston E, McVetta J, et al. . Automated detection and classification of type 1 versus type 2 diabetes using electronic health record data. Diabetes Care 2013;36:914–21. 10.2337/dc12-0964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schroeder EB, Donahoo WT, Goodrich GK, et al. . Validation of an algorithm for identifying type 1 diabetes in adults based on electronic health record data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2018;27:1053–9. 10.1002/pds.4377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCoy RG, Dykhoff HJ, Sangaralingham L, et al. . Adoption of new glucose-lowering medications in the U.S.-The case of SGLT2 inhibitors: nationwide cohort study. Diabetes Technol Ther 2019;21:702–12. 10.1089/dia.2019.0213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aron DC. No "Black swan": unintended but not unanticipated consequences of diabetes performance measurement. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2013;39:106–8. 10.1016/S1553-7250(13)39015-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnold SV, Lipska KJ, Wang J, et al. . Use of intensive glycemic management in older adults with diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:1190–4. 10.1111/jgs.15335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipska KJ, Ross JS, Miao Y, et al. . Potential overtreatment of diabetes mellitus in older adults with tight glycemic control. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:356–62. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maciejewski ML, Mi X, Sussman J, et al. . Overtreatment and Deintensification of diabetic therapy among Medicare beneficiaries. J Gen Intern Med 2018;33:34–41. 10.1007/s11606-017-4167-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sussman JB, Kerr EA, Saini SD, et al. . Rates of Deintensification of blood pressure and glycemic medication treatment based on levels of control and life expectancy in older patients with diabetes mellitus. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1942–8. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tseng C-L, Soroka O, Maney M, et al. . Assessing potential glycemic overtreatment in persons at hypoglycemic risk. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:259–68. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hambling CE, Seidu SI, Davies MJ, et al. . Older people with type 2 diabetes, including those with chronic kidney disease or dementia, are commonly overtreated with sulfonylurea or insulin therapies. Diabet Med 2017;34:1219–27. 10.1111/dme.13380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thorpe CT, Gellad WF, Good CB, et al. . Tight glycemic control and use of hypoglycemic medications in older veterans with type 2 diabetes and comorbid dementia. Diabetes Care 2015;38:dc140599–95. 10.2337/dc14-0599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCoy RG, Van Houten HK, Ross JS, et al. . Hba1C overtesting and overtreatment among US adults with controlled type 2 diabetes, 2001-13: observational population based study. BMJ 2015;351:h6138. 10.1136/bmj.h6138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pogach L, Aron D. The other side of quality improvement in diabetes for seniors: a proposal for an overtreatment glycemic measure. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1510–2. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.4392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snyder L, Neubauer RL, American College of Physicians Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee . Pay-For-Performance principles that promote patient-centered care: an ethics manifesto. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:792–4. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-11-200712040-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sirovich BE, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. Too little? Too much? Primary care physicians' views on US health care: a brief report. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1582–5. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caverly TJ, Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, et al. . Appropriate prescribing for patients with diabetes at high risk for hypoglycemia: national survey of Veterans Affairs health care professionals. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1994–6. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zoungas S, Patel A, Chalmers J, et al. . Severe hypoglycemia and risks of vascular events and death. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1410–8. 10.1056/NEJMoa1003795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goto A, Arah OA, Goto M, et al. . Severe hypoglycaemia and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis with bias analysis. BMJ 2013;347:f4533. 10.1136/bmj.f4533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khunti K, Davies M, Majeed A, et al. . Hypoglycemia and risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in insulin-treated people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a cohort study. Diabetes Care 2015;38:316–22. 10.2337/dc14-0920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cryer PE. Death during intensive glycemic therapy of diabetes: mechanisms and implications. Am J Med 2011;124:993–6. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu C-L, Shen H-N, Hu SC, et al. . A population-based study of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease in association with prior history of hypoglycemia among patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2016;39:1571–8. 10.2337/dc15-2418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCoy RG, Van Houten HK, Ziegenfuss JY, et al. . Self-report of hypoglycemia and health-related quality of life in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Endocr Pract 2013;19:792–9. 10.4158/EP12382.OR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis SN, Duckworth W, Emanuele N, et al. . Effects of severe hypoglycemia on cardiovascular outcomes and death in the Veterans Affairs diabetes trial. Diabetes Care 2019;42:157–63. 10.2337/dc18-1144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonds DE, Miller ME, Bergenstal RM, et al. . The association between symptomatic, severe hypoglycaemia and mortality in type 2 diabetes: retrospective epidemiological analysis of the ACCORD study. BMJ 2010;340:b4909. 10.1136/bmj.b4909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seaquist ER, Miller ME, Bonds DE, et al. . The impact of frequent and unrecognized hypoglycemia on mortality in the ACCORD study. Diabetes Care 2012;35:409–14. 10.2337/dc11-0996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCoy RG, Van Houten HK, Ziegenfuss JY, et al. . Increased mortality of patients with diabetes reporting severe hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1897–901. 10.2337/dc11-2054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Styles E, Kidney RSM, Carlin C, et al. . Diabetes treatment, control, and hospitalization among adults aged 18 to 44 in Minnesota, 2013-2015. Prev Chronic Dis 2018;15:E142. 10.5888/pcd15.180255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lipska KJ, Yao X, Herrin J, et al. . Trends in drug utilization, glycemic control, and rates of severe hypoglycemia, 2006-2013. Diabetes Care 2017;40:468–75. 10.2337/dc16-0985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reiss SK, Ross-Degnan D, Zhang F, et al. . Effect of switching to a high-deductible health plan on use of chronic medications. Health Serv Res 2011;46:1382–401. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01252.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wharam JF, Zhang F, Eggleston EM, et al. . Diabetes outpatient care and acute complications before and after high-deductible insurance enrollment: a natural experiment for translation in diabetes (NEXT-D) study. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:358–68. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCoy RG, Houten HVAN, Ross J, et al. . 38-OR: differences in diabetes medication use between commercial and Medicare advantage beneficiaries, 2013-2018. Diabetes 2020;69:38-OR 10.2337/db20-38-OR [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spanakis EK, Golden SH. Race/ethnic difference in diabetes and diabetic complications. Curr Diab Rep 2013;13:814–23. 10.1007/s11892-013-0421-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim S, Boye KS. Excessive hospitalizations and its associated economic burden among people with diabetes in the United States. Value Health 2009;12:267–72. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00443.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sarkar U, Karter AJ, Liu JY, et al. . Hypoglycemia is more common among type 2 diabetes patients with limited health literacy: the diabetes study of northern California (DISTANCE). J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:962–8. 10.1007/s11606-010-1389-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lipska KJ, Warton EM, Huang ES, et al. . HbA1c and risk of severe hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes: the diabetes and aging study. Diabetes Care 2013;36:3535–42. 10.2337/dc13-0610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karter AJ, Moffet HH, Liu JY, et al. . Surveillance of Hypoglycemia-Limitations of emergency department and hospital utilization data. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:987. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, McCoy RG. Measuring what matters in diabetes. JAMA 2019;321:1865. 10.1001/jama.2019.4310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Battelino T, Danne T, Bergenstal RM, et al. . Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: recommendations from the International consensus on time in range. Diabetes Care 2019;42:1593–603. 10.2337/dci19-0028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjdrc-2020-001878supp001.pdf (774.1KB, pdf)