This cross-sectional study assesses how patients with cancer perceive cancer treatment and follow-up care (including experiences with telephone and video consultations) and patients’ well-being in comparison with a norm population during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key Points

Questions

How do Dutch patients with cancer perceive care and well-being during the COVID-19 crisis, in comparison with a matched norm population?

Findings

In this cross-sectional analysis within a population-based registry of 4094 Dutch patients with cancer and 977 matched norm participants, up to 29% of patients reported that their appointment was canceled or replaced by a telephone or video consultation, related to systemic therapy. Quality of life, anxiety, and depression were comparable, but norm participants significantly more often reported loneliness (12% vs 7%) than patients with cancer.

Meaning

Long-term evaluation is needed, but additional supportive care for patients with cancer does not appear to be required at this moment.

Abstract

Importance

As the resolution of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) crisis is unforeseeable, and/or a second wave of infections may arrive in the fall of 2020, it is important to evaluate patients’ perspectives to learn from this.

Objective

To assess how Dutch patients with cancer perceive cancer treatment and follow-up care (including experiences with telephone and video consultations [TC/VC]) and patients’ well-being in comparison with a norm population during the COVID-19 crisis.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Cross-sectional study of patients participating in the Dutch Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial Treatment and Long-term Evaluation of Survivorship (PROFILES) registry and a norm population who completed a questionnaire from April to May 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Logistic regression analysis assessed factors associated with changes in cancer care (treatment or follow-up appointment postponed/canceled or changed to TC/VC). Differences in quality of life, anxiety/depression, and loneliness between patients and age-matched and sex-matched norm participants were evaluated with regression models.

Results

The online questionnaire was completed by 4094 patients (48.6% response), of whom most were male (2493 [60.9%]) and had a mean (SD) age of 63.0 (11.1) years. Of these respondents, 886 (21.7%) patients received treatment; 2725 (55.6%) received follow-up care. Treatment or follow-up appointments were canceled for 390 (10.8%) patients, whereas 160 of 886 (18.1%) in treatment and 234 of 2725 (8.6%) in follow-up had it replaced by a TC/VC. Systemic therapy, active surveillance, or surgery were associated with cancellation of treatment or follow-up appointment. Younger age, female sex, comorbidities, metastasized cancer, being worried about getting severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and receiving supportive care were associated with replacement of a consultation with a TC/VC. Patients and norm participants reported that the COVID-19 crisis made them contact their general practitioner (852 of 4068 [20.9%] and 218 of 979 [22.3%]) or medical specialist/nurse (585 of 4068 [14.4%] and 144 of 979 [14.7%]) less quickly when they had physical complaints or concerns. Most patients who had a TC/VC preferred a face-to-face consultation, but 151 of 394 (38.3%) were willing to use a TC/VC again. Patients with cancer were more worried about getting infected with SARS-CoV-2 compared with the 977 norm participants (917 of 4094 [22.4%] vs 175 of 977 [17.9%]). Quality of life, anxiety, and depression were comparable, but norm participants more often reported loneliness (114 of 977 [11.7%] vs 287 of 4094 [7.0%]) than patients with cancer (P = .009).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with cancer in the Netherlands, 1 in 3 reported changes in cancer care in the first weeks of the COVID-19 crisis. Long-term outcomes need to be monitored. The crisis may affect the mental well-being of the general population relatively more than that of patients with cancer.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has affected cancer care worldwide. In the Netherlands, a lockdown was introduced on March 23, 2020. Planned cancer surgical procedures and systemic treatments were delayed or stopped. The Netherlands Cancer Registry reported a 25% decrease in the absolute number of cancer diagnoses.1 Furthermore, to prevent the potential risk of an infection, patients with cancer were advised to not visit the hospital unless strictly needed.2

As a result, cancer patient organizations were alarming the public about postponed cancer diagnoses and operations and delayed systemic treatments. Cancer centers reported high anxiety levels among patients with cancer and a “skyrocketing” demand for counseling and mental health care.3 At the same time, hospitals were quickly scaling up virtual health care by means of video consultation (VC),4 while others used telephone consultation (TC), as alternatives to face-to-face visits.5

Our research objectives were to understand (1) how patients perceive cancer treatment and follow-up care (including experiences with video and telephone consultations), and (2) the well-being of patients with cancer in comparison with an age-matched and sex-matched norm population without cancer during the COVID-19 crisis.

Methods

Cross-sectional assessment was performed within a longitudinal cohort/registry study. Patients participating in the Dutch Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial Treatment and Long-term Evaluation of Survivorship (PROFILES)6 registry were asked to complete an additional COVID-19–related questionnaire if they had previously signed informed consent and gave approval to be invited for additional questionnaires. Vital status was verified on February 1, 2020. Patients were invited from April 18, 2020; a norm population—representative of the Dutch population7—was invited from May 4, 2020. The Institutional Review Board of the Netherlands Cancer Institute (IRBd20-115) approved this study.

Because the norm population was smaller and representative of the general Dutch population (thus younger than the cancer population), we were not able to match 1:1 without replacement. We used the frequency matching method: based on the frequency distribution by stratum (defined by age categories and sex), the number of norm participants that can be matched to the patients was maximized (n = 977).

Sociodemographic and clinical variables were obtained from the Netherlands Cancer Registry. Current cancer and therapy status was self-reported. Comorbidity was assessed with the adapted Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire.8 Five questions about experience with TCs or VCs were derived from the questionnaire by Barsom et al.9 Health-related quality of life was assessed with the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30),10 and a single item11 was used to assess worry about health in the future. Anxiety and depression symptoms were assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.12 Loneliness was assessed with the De Jong Gierveld short scales.13

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to evaluate the independent association of a priori selected variables (age, sex, education level, marital status, living situation, cancer type, cancer stage, metastasis, BMI, comorbidity, current treatment, current supportive care and worry about getting severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 [SARS-CoV-2]) with changes in treatment or follow-up care. General linear models were computed to assess the differences in health-related quality of life, worry about getting SARS-CoV-2, anxiety/depression, and loneliness between patients with cancer and matched controls, adjusted for potential confounders (education level, living situation, comorbidity, COVID-19 status). The odds of changes in treatment or follow-up appointment vs no changes were calculated, separately, for patients currently being treated/had to start treatment and for patients in follow-up. Linear, logistic, and multinomial regression models were computed to assess the differences in health-related quality of life, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and loneliness scores, respectively. All analyses were 2-sided, and P values less than .05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4. (SAS Institute).

Results

The online questionnaire was completed by 4094 of 8428 patients (48.6% response) and 2351 of 3509 norm participants (67.0% response) (eFigure in the Supplement). A total of 977 of 3509 (27.8%) cancer-free norm participants could be age-matched and sex-matched to the patients with cancer (eTable 1 and eTable 2 in the Supplement). Of 886 patients who were currently being treated or had to start treatment, 96 (10.8%) had their treatment postponed or canceled, and 160 (18.1%) had their consult changed to a TC/VC. Among 2725 patients who received follow-up care, 294 (10.8%) had their appointment postponed or canceled, and 234 (8.6%) had their consult changed to a TC/VC. Variables associated with changes in treatment or follow-up are summarized in Table 1. Patients and norm participants reported that the COVID-19 crisis made them contact their general practitioner (852 of 4068 [20.9%] and 218 of 979 [22.3%]) or medical specialist/nurse (585 of 4068 [14.4%] and 144 of 979 [14.7%]) less quickly when they had physical complaints, questions, or concerns (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Multivariable Logistic Regression Analyses of Changes in Treatment and Follow-up Care vs No Changes in Patients Still Receiving Treatment or Follow-up (n = 3611)a.

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients currently being treated or have to start treatment (n = 886) | Patients completed treatment, now in follow-up (n = 2725) | |||

| Treatment postponed or canceled | Consult changed to TC or VC | Follow-up postponed or canceled | Consult changed to TC or VC | |

| No. (%) | 96 (10.8) | 160 (18.1) | 294 (10.8) | 234 (8.6) |

| Age, per year increase | 0.98 (0.95-1.00) | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | 0.99 (0.97-1.00)b |

| Sex (reference = male), female | 0.93 (0.57-1.51) | 1.52 (1.03-2.24)b | 1.15 (0.87-1.50) | 1.03 (0.76-1.39) |

| Married/partnered (reference = no partner) | 1.00 (0.53-1.86) | 0.91 (0.55-1.50) | 1.38 (0.95-2.02) | 0.67 (0.47-0.96)b |

| BMI,c per unit increase | 1.00 (0.96-1.04) | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) | 1.01 (0.99-1.04) | 0.97 (0.94-1.00) |

| Comorbidities (reference = none) | ||||

| 1 | 0.75 (0.43-1.34) | 1.30 (0.81-2.09) | 1.29 (0.97-1.72) | 1.52 (1.06-2.16)b |

| >1 | 0.96 (0.57-1.64) | 1.69 (1.08-2.65)b | 0.83 (0.60-1.15) | 1.65 (1.15-2.37)d |

| Metastasis (reference = no) | 0.87 (0.54-1.40) | 1.66 (1.09-2.53)b | 0.62 (0.38-1.01) | 0.83 (0.51-1.35) |

| Current treatment (reference = no) | ||||

| Surgery | 0.93 (0.43-1.99) | 1.42 (0.77-2.64) | 2.46 (1.12-5.42)b | 1.21 (0.46-3.20) |

| Radiotherapy | 1.34 (0.60-2.98) | 1.06 (0.53-2.13) | 0.72 (0.17-3.04) | 1.14 (0.26-4.96) |

| Chemotherapy | 0.84 (0.49-1.42) | 1.12 (0.73-1.70) | 0.67 (0.14-3.10) | 1.02 (0.24-4.36) |

| Immunotherapy | 1.86 (1.05-3.29)b | 1.45 (0.90-2.34) | 0.77 (0.10-6.16) | 1.12 (0.21-5.98) |

| Targeted therapy | 0.44 (0.13-1.51) | 1.32 (0.66-2.64) | 11.95 (1.66-86.24)b | 0.84 (0.08-8.80) |

| Hormonal therapy | 1.91 (1.07-3.40)b | 1.25 (0.75-2.07) | 1.84 (1.06-3.20)b | 0.79 (0.37-1.66) |

| Active surveillance | 2.23 (1.11-4.49)b | 1.24 (0.63-2.44) | 0.91 (0.57-1.47) | 1.34 (0.85-2.12) |

| Symptom management | 0.58 (0.19-1.74) | 0.85 (0.40-1.81) | 1.76 (0.85-3.67) | 2.57 (1.30-5.07)d |

| Current supportive care (reference = no) | ||||

| Psychological care | 0.88 (0.38-2.03) | 1.20 (0.65-2.24) | 1.16 (0.64-2.09) | 1.80 (1.06-3.07)b |

| General practitioner | 0.79 (0.29-2.14) | 0.79 (0.37-1.70) | 0.89 (0.40-1.97) | 1.62 (0.85-3.08) |

| Dietitian | 1.15 (0.59-2.25) | 1.89 (1.15-3.12)b | 1.25 (0.77-2.03) | 1.38 (0.85-2.24) |

| Physical therapy | NA | NA | 0.57 (0.05-5.94) | 11.64 (2.64-51.32)d |

| Oncological rehabilitation | 1.24 (0.44-3.50) | 0.55 (0.20-1.53) | 1.46 (0.65-3.26) | 2.21 (1.08-4.52)b |

| Oncology nurse | 0.62 (0.36-1.06) | 0.83 (0.55-1.24) | 0.75 (0.49-1.15) | 2.07 (1.43-2.99)d |

| Support groups | 1.75 (0.56-5.52) | 2.70 (1.05-6.94)b | 0.78 (0.23-2.63) | 1.60 (0.63-4.04) |

| Worried about getting infected with SARS-CoV-2e | 1.54 (0.98-2.44) | 1.81 (1.26-2.62)d | 1.02 (0.74-1.39) | 1.66 (1.22-2.27)d |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; NA, not applicable: no estimates; OR, odds ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TC, telephone consultation; VC, video consultation.

Missing data: worried about getting infected with SARS-CoV-2 (n = 42). Missing values were handled as reference category by using dummy variables. Current supportive care services reported by less than 1% of the population (sexologist, creative therapy, religious/spiritual care, see also in eTable 2 in the Supplement) were omitted.

P < .05.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

P < .01.

Quite a bit/very much vs a little/not at all.

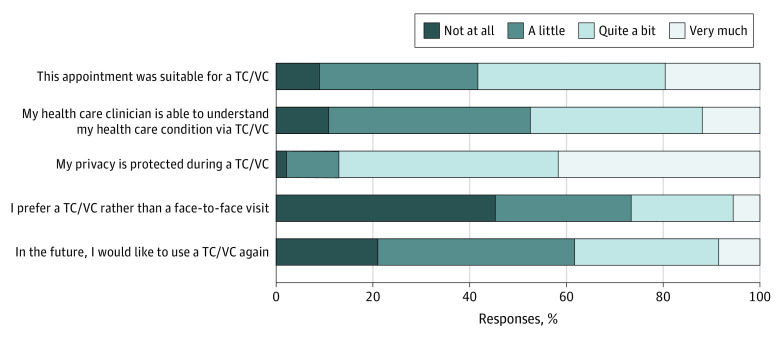

A total of 394 of 3611 (10.9%) patients had their face-to-face appointment replaced by a TC (n = 375) or VC (n = 19). Of the 394 patients, some considered their appointment not at all (35 [8.9%]) or just a little (130 [33.0%]) suitable for a TC/VC, whereas 229 (58.1%) thought it was suitable (Figure). Although most patients (293 [74.4%]) preferred a face-to-face meeting, 151 (38.3%) were willing to have a TC/VC again in the future.

Figure. Experiences With Telephone Consultation (TC) or Video Consultation (VC) Among Patients With Cancer Who Had Their Face-to-Face Appointment Changed Into a TC or VC (N = 394).

Patients reported lower functioning and more fatigue, dyspnea, and insomnia than norm participants, but these differences were not clinically relevant (Table 2). Patients worried more about their health in the future than the norm-population (mean [SD], 28.1 [25] vs 20.9 [23]; P < .001) and were more worried about becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2 (917 of 4094 [22.4%] vs 175 of 977 [17.9%] responded they were “quite a bit” or “very much” worried; P = .01). More norm participants than patients reported being lonely (Table 2).

Table 2. Quality of Life, Symptoms, Anxiety, Depression, and Loneliness of Patients With Cancer and Matched Norm Population.

| Outcome | Mean (SD)a | P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with cancer (n = 4094) | Matched norm population based on age and sex (n = 977) | ||

| EORTC QLQ-C30 [0-100] | |||

| Physical functioning | 88.6 (15.5) | 90.3 (15.5) | <.001 |

| Role functioning | 82.6 (24.8) | 89.2 (20.8) | <.001 |

| Emotional functioning | 85.2 (17.3) | 86.8 (17.1) | .01 |

| Cognitive functioning | 88.2 (17.4) | 92.7 (14.7) | <.001 |

| Social functioning | 88.0 (21.8) | 94.2 (15.7) | <.001 |

| Global quality of life | 76.2 (18.1) | 74.8 (17.4) | .07 |

| Fatigue | 19.8 (21.8) | 15.2 (19.4) | <.001 |

| Pain | 12.4 (20.8) | 12.2 (21.1) | .42 |

| Dyspnea | 9.9 (19.3) | 7.3 (17.2) | <.001 |

| Insomnia | 18.2 (25.2) | 15.0 (24.0) | <.001 |

| Worried about health in future | 28.1 (25.3) | 20.9 (23.2) | <.001 |

| Worried about getting infected with SARS-CoV-2 | 36.8 (23.6) | 33.6 (23.0) | .02 |

| Not at all/a little, No. (%) | 3135 (77.6) | 811 (82.1) | 1.00 [Reference] |

| Quite a bit/very much, No. (%) | 917 (22.4) | 175 (17.9) | .01 |

| HADS (0-21), No. (%) | |||

| Anxiety | 486 (11.8) | 111 (11.2) | .01 |

| Depression | 406 (9.9) | 120 (12.2) | .39 |

| Overall loneliness, No. (%) | |||

| Not lonely | 2273 (56.1) | 490 (50.2) | 1.00 [Reference] |

| Somewhat lonely | 1492 (36.8) | 373 (38.2) | .65 |

| Lonely | 287 (7.1) | 114 (11.7) | .009 |

Abbreviations: EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Crude means and SDs are shown.

Adjusted for educational level, living situation, body mass index, comorbidity, and coronavirus disease 2019 status. General linear models were used for continuous variables, logistic regression analysis for binary variables and multinomial logistic regression for categorical variables. Percentages do not always add up to 100 because they have been rounded to whole numbers. Missing data: EORTC QLQ-C30 (n = 29 patients); worried about getting infected with SARS-CoV-2 (n = 42 patients, n = 1 norm); HADS (n = 51 patients); loneliness (n = 42 patients).

Discussion

Our finding that 19% to 29% of patients reported changes in treatment or follow-up within 4 to 6 weeks after the first announcement of the Dutch COVID-19 lockdown is comparable with a recent report from 7 comprehensive cancer centers that described a 20% to 30% decrease in the overall number of patients with cancer admitted to most centers.3

In line with the advice of experts3,14 to temporarily prevent vulnerable patients from coming to the hospital, we found that patients treated with immune therapy or targeted therapy and those who had comorbid diseases or metastasized cancer were more likely to report changes in cancer care, although sometimes the odds ratios had wide CIs.

The reluctance of patients and norm participants to contact their health care clinicians in the COVID-19 crisis was consistent with the lower cancer incidence in the Netherlands in March 20201 and expected by general practitioners: “Patients might be reluctant to present because of fear of interacting with others, limited capacity to use video or teleconsultations, and concerns about wasting the doctor’s time.”15(p748)

Eleven percent had their consultation converted into a TC/VC, and although the majority preferred face-to-face contact, 39% were willing to use a TC/VC again in the near future. This finding may help change our care for patients not only during the potentially long-lasting COVID-19 period, but also beyond.

The findings of the present study confirm previous anecdotal reports of patients with cancer being afraid,3 with 23% reporting to be worried about getting COVID-19. But almost similar anxiety and depression levels in the norm population, and even higher prevalence of loneliness (albeit the difference was not clinically relevant), suggest that the impact of the crisis may be larger in the norm population than in patients with cancer. Restricted social contacts and limited freedom of movement may have less impact on patients with cancer than norm participants, as they often already report decreased social functioning after a cancer diagnosis, which may not have changed much during COVID-19.

Limitations and Strengths

The present study has some notable strengths, including the use of the large, population-based PROFILES registry with information about cancer diagnosis, stage, and treatment, and the use of a matched norm-population and validated scales. A limitation of the study is that we only invited our online cancer participants, of whom about half responded, whereas 67% of the norm participants responded. Even though our sample included a good representation of patients in different phases of their disease, the cancer respondents reported relatively high functioning scores compared with our previous findings in similar cohorts. This may have resulted in an underestimated impact of the COVID-19 crisis on perceived changes in care and well-being, as specifically the most vulnerable patients were advised not to visit a hospital if not strictly needed.

Conclusions

In conclusion, up to 1 in 3 patients with cancer in the Netherlands experienced postponement or cancellation of their treatment or follow-up appointment or replacement with a TC/VC in the first weeks of the COVID-19 crisis. Longitudinal evaluation will reveal whether this has an association with their long-term health outcomes. The COVID-19 pandemic may affect the mental well-being of the general population more than that of patients with cancer.

eFigure. Flow-chart of COVID-19 study within PROFILES cohorts.

eTable 1. Sociodemographic, comorbidity and COVID-19 characteristics of cancer patients and age- and sex- matched norm population.

eTable 2. Disease and treatment characteristics of cancer patients.

eTable 3. Changes in contact with health care providers because of the COVID-19 crisis when a person has physical complaints, questions or concerns.

eTable 4. Sensitivity analysis of quality of life, symptoms, anxiety and depression and loneliness of cancer patients and matched norm population based on different matching factors.

References

- 1.Dinmohamed AG, Visser O, Verhoeven RHA, et al. . Fewer cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 epidemic in the Netherlands. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):750-751. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30265-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenbaum L The untold toll—the pandemic’s effects on patients without Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):2368-2371. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2009984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van de Haar J, Hoes LR, Coles CE, et al. . Caring for patients with cancer in the COVID-19 era. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):665-671. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0874-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barsom EZ, Feenstra TM, Bemelman WA, Bonjer JH, Schijven MP. Coping with COVID-19: scaling up virtual care to standard practice. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):632-634. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0845-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webster P Virtual health care in the era of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1180-1181. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30818-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van de Poll-Franse LV, Horevoorts N, van Eenbergen M, et al. ; Profiles Registry Group . The Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long term Evaluation of Survivorship registry: scope, rationale and design of an infrastructure for the study of physical and psychosocial outcomes in cancer survivorship cohorts. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(14):2188-2194. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mols F, Husson O, Oudejans M, Vlooswijk C, Horevoorts N, van de Poll-Franse LV. Reference data of the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire: five consecutive annual assessments of approximately 2000 representative Dutch men and women. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(10):1381-1391. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1481293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(2):156-163. doi: 10.1002/art.10993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barsom EZ, Jansen M, Tanis PJ, et al. . Video consultation during follow up care: effect on quality of care and patient- and provider attitude in patients with colorectal cancer. Surg Endosc. Published online March 20, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-07499-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. . The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365-376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Group EORTC Quality of Life Group Item Library. Accessed October 26, 2020. https://www.eortc.be/itemlibrary/

- 12.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Jong Gierveld J, Van Tilburg T. The De Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. Eur J Ageing. 2010;7(2):121-130. doi: 10.1007/s10433-010-0144-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrag D, Hershman DL, Basch E. Oncology practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2005-2006. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones D, Neal RD, Duffy SRG, Scott SE, Whitaker KL, Brain K. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the symptomatic diagnosis of cancer: the view from primary care. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):748-750. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30242-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Flow-chart of COVID-19 study within PROFILES cohorts.

eTable 1. Sociodemographic, comorbidity and COVID-19 characteristics of cancer patients and age- and sex- matched norm population.

eTable 2. Disease and treatment characteristics of cancer patients.

eTable 3. Changes in contact with health care providers because of the COVID-19 crisis when a person has physical complaints, questions or concerns.

eTable 4. Sensitivity analysis of quality of life, symptoms, anxiety and depression and loneliness of cancer patients and matched norm population based on different matching factors.