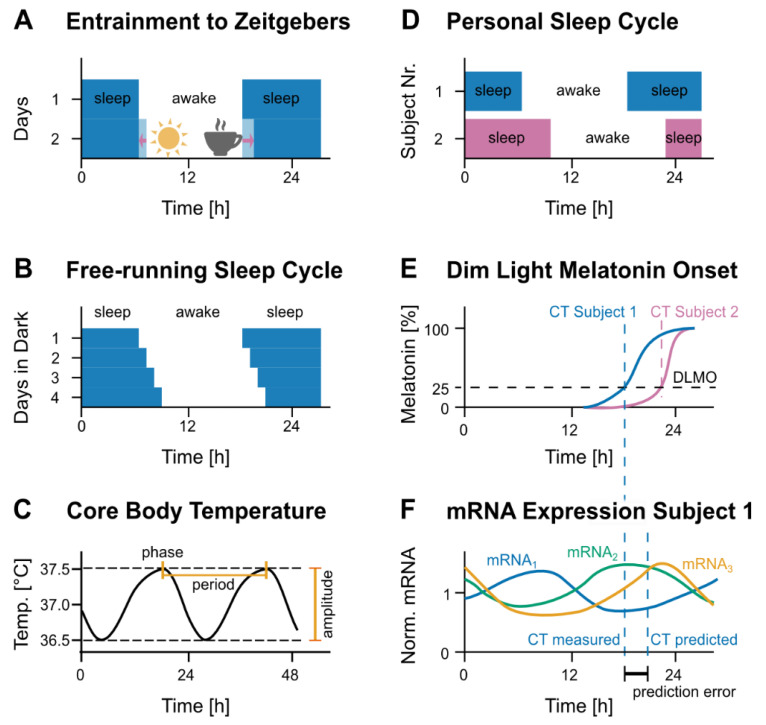

Figure 2.

Circadian oscillations in humans. (A) The circadian rhythm is evident from the sleep/wake cycle of humans. Subjected to a normal day-night rhythm, humans are awake (white) and sleep (blue) with a period adapted to 24 h. Normally, the first light acts as a strong zeitgeber that entrains the subject to its rhythm. Other zeitgebers include temperature, food or the cup of coffee in the evening, which likely delays sleep onset. (B) Under constant light conditions, humans retain a rhythm of wake (white) and sleep (blue) phases with a period of around 24 h. In this example, the period is slightly longer than 24 h, thus shifting wake and sleep from day to day. (C) The core body temperature shows circadian oscillations. The phase (also named acrophase) is defined as the first peak of the oscillation, the time between two peaks is the period and the amplitude is the difference between peak and trough. (D) Indicated are the awake (white) and sleep (colored) phases for two subjects. Subject 1 (blue) has an earlier phase than subject 2 (pink). (E) To measure the dim-light melatonin onset (DLMO), subjects are kept under dim-light conditions during the evening, with hourly sampling for subsequent melatonin quantification. The circadian phase is defined as the time when the concentration of melatonin reaches an absolute (e.g., 2 pg/mL) or relative (e.g., 25%) threshold [15]. (F) The analysis of circadian oscillations of a set of genes for a given subject (here visualized with profile sketches for three imaginary transcripts, mRNA1, mRNA2, mRNA3) allows to predict the circadian time of that subject. The difference between predicted and actual circadian time constitutes the prediction error.