Abstract

E3 ubiquitin ligases are of interest as drug targets due to their involvement in the regulation of the functions and interactions of several proteins. Various E3 ligase complexes are considered oncogenes or tumor suppressors associated with the development of melanoma. These proteins regulate the functions of various signaling pathways and proteins, such as p53 and Notch. The aim of the present study was to determine the expression levels of F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7 (FBXW7), c-Myc, MDM2 and p53 proteins in samples from patients with dysplastic nevi or melanoma, and to evaluate their association with clinicopathological parameters and prognosis of the disease. Paraffin blocks with postoperative material from 100 patients diagnosed with dysplastic moles or melanoma were used in the present study. Tissue microarrays and immunohistochemistry were used to examine FBXW7, c-Myc, MDM2 and p53 protein expression. The results revealed that there was significantly lower FBXW7 expression in advanced melanoma compared with dysplastic nevus, melanoma in situ and stage pT1 melanoma (P<0.001). Additionally, there was a statistically significant association between the expression levels of FBXW7 and the morphological type of the tumor (P<0.001). In addition, there was a strong positive association between FBXW7 expression and the changes in c-Myc expression (P<0.02), and a strong trend was observed between decreased FBXW7 expression and a higher risk of death in patients, with the major factor in patient mortality being the stages of melanoma. Additionally, p53 expression was associated with the depth of melanoma invasion and the morphological type of the tumor. In summary, FBXW7 expression exhibited the highest statistically significant prognostic value and associations with advanced melanoma. As the majority of FBXW7 substrates are oncoproteins, their degradation by FBXW7 may highlight these proteins as potential targets for the treatment of melanoma.

Keywords: melanoma, F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7, p53, c-Myc, MDM2, ubiquitin ligases, prognostic factor

Introduction

E3 ligases of the ubiquitin proteasome system are involved in the regulation of protein functions, stability and degradation; some of the components of the E3 ligase complexes are considered oncogenes or tumor suppressors with regards to the development of melanoma (1,2). Previous studies have focused on identifying gene products whose expression is altered as a disease progresses, as these may be novel molecular targets for the treatment of melanoma or new prognostic markers to track the course of the disease (1,3).

F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7 (FBXW7) is a well-studied F-box-containing protein (4–6). F-box proteins are subunits of SCF-type E3 ligases that recognize the substrate, bind to it and target it for ubiquitination and degradation (4). It has been demonstrated that FBXW7 can act as a tumor suppressor by negatively regulating the expression levels of several protein oncogenes, including c-Myc, Notch, cyclin E and c-Jun (5–8). In melanoma, FBXW7 acts as a tumor suppressor. Studies have revealed that FBXW7 expression is significantly decreased in primary and metastatic melanoma samples compared with samples of dysplastic nevi, and that this decreased FBXW7 expression is associated with melanoma progression (5,9). However, the mechanism underlying the decrease in FBXW7 expression in tumors remains unclear.

One of the most important regulators of FBXW7 is p53 (10,11). p53 is a major tumor suppressor protein, with mutations detected in several types of human cancer, such as breast cancer, bone and soft tissue sarcoma, brain tumor, adrenocortical carcinoma, leukemia, stomach cancer and colorectal cancer (12–17). Mao et al (11) revealed that FBXW7 mediates the critical role of p53 in responding to DNA damage, suggesting that FBXW7 may be a p53-dependent gene tumor suppressor involved in tumor development. Further studies have demonstrated that FBXW7 expression may be restored by targeting the p53 signaling pathway (10,11).

c-Myc is a protein that is found in ~70% of all types of human cancer, including leukemia (18,19), sarcoma (20) and hepatocellular carcinoma (21,22). c-Myc is important for normal cell growth, and cellular Myc protein levels are tightly controlled (23,24). At least four different ubiquitin ligase complexes can target c-Myc for proteasomal degradation, including FBXW7 (23). Previous studies have revealed increased c-Myc expression in advanced and metastatic melanoma (25–29).

The E3 ubiquitin ligase MDM2 is a major negative regulator of the p53 tumor suppressor protein, and by suppressing p53, MDM2 promotes tumor development (30). In normal cells, the presence of MDM2 is essential for maintaining p53 protein expression at a basal level by regulating its ubiquitination and degradation in the 26S proteasome (31,32). In addition, MDM2 suppresses p53 function by directly binding to the transcriptional binding site of p53, thereby preventing its interaction with transcription factors (33–35). p53 and MDM2 interact and form a negative autoregulation loop in which elevated p53 transcriptional levels activate MDM2, which in turn decrease p53 levels (15,30,36).

The aim of the present study was to determine the protein expression levels of FBXW7, c-Myc, MDM2 and p53 in patients with dysplastic nevi or melanoma using tissue samples. Additionally, the associations between the expression levels of these proteins with clinicopathological parameters and prognosis of the disease were evaluated to determine whether these proteins may be used as prognostic factors for patients with melanoma, potentially allowing for improved modeling of effective personalized treatment of melanoma.

Materials and methods

Study population

The present study was performed on tissue microarray (TMA) sections obtained from paraffin blocks of postoperative material from 100 patients with dysplastic nevi or skin melanoma treated at the National Cancer Institute (Vilnius, Lithuania) between January 2013 and December 2018. Histological and immunohistochemical analysis was performed at the National Center of Pathology affiliated to Vilnius University Hospital SantarosKlinikos (Vilnius, Lithuania). The present study was approved by the Vilnius Regional Committee of Biomedical Research (approval no. 158200-16-878-387; approval date, 2016-12-13).

The present study included patients >18 years old with surgically removed and histologically confirmed dysplastic nevi or melanoma. The present study included 16 patients diagnosed with dysplastic nevi, 16 with in situ melanoma, 17 with pathological tumor (pT) 1 stage, 17 with pT2 stage, 17 with pT3 stage and 17 with pT4 stage melanoma. The following clinicopathological parameters of patients were evaluated: Sex, age, pT stage (37), morphological tumor type, ulceration and localization. Of the 100 cases under analysis, 39 were male and 61 were female, with a median age of 61 years (range, 21–92 years).

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis

The TMAs were constructed from 10% buffered formalin-fixed (at room temperature for ~24 h) paraffin-embedded tissue blocks; 2-mm diameter cores were punctured from the tumor block as randomly selected by a pathologist (1 core per patient), thus producing 2 TMAs constructed using the tissue arraying instrument (TMA Master; 3DHISTECH, Ltd.). The TMA blocks for immunohistochemistry were cut into 2-µm-thick sections and mounted on TOMO adhesion glass slides (Matsunami Glass Ind., Ltd.). The sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated in a descending alcohol series, and antigen retrieval for antibodies against p53 and c-Myc proteins was performed using DAKO PTLink system with EnVision FLEX Target buffer (pH 8.0) at 95°C for 20 min (both from Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.), while that for antibodies against FBXW7 and MDM2 proteins was performed using a Ventana Benchmark Ultra system with Cell Conditioning solution (pH 8.5) at 100°C for 36 min. (both from Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.; Roche Diagnostics). The sections were blocked with FLEX Peroxide Block (cat. no. SM801; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) at room temperature for 5 min for p53, 10 min for c-Myc and 8 min for FBXW7 and MDM2.Subsequently, the sections were incubated with antibodies against p53 (1:200; cat. no. M7001, clone DO-7; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) and c-Myc (1:40; cat. no. ab32072, cloneY69; Abcam) at room temperature for 30 min, then incubated using a DAKO EnVision FLEX system (Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) for 20 min at room temperature. Incubation with antibodies against FBXW7 (1:50; cat. no. MA5-26562, clone OTI6F5; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and MDM2 (1:250; cat. no. MA1-113, clone IF2; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was performed at 37°C for 32 min and then using the VentanaUltraview DAB detection kit (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.; Roche Diagnostics) for 8 min at 37°C. Finally, the sections were developed using DAB, counterstained using Mayer's hematoxylin at room temperature for 10 min and mounted. Negative controls were performed by omitting the application of the primary antibody. The IHC slides were observed using a light microscope at a magnification of ×20 (0.5 µm resolution) using a bright field AperioScanScope XT Slide Scanner (Leica Microsystems, Inc.).

Assessment of FBXW7, c-Myc, MDM2 and p53 expression

The pathologist performed a visual assessment of staining intensity and overall percentage of cells staining. The intensity of protein immunostaining was scored as 0–3: 0, Negative staining; 1, weak staining; 2, moderate staining; and 3, strong staining. The percentage of nuclear staining was graded in 4 categories: 1, 0–25%; 2, 26–50%; 3, 51–75%; and 4, 76–100%. The combined score obtained by multiplying the staining intensity score with the staining percentage score was graded as follows: 0–6, Low expression; and 7–12, high expression.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA v11.2 (StataCorp LP). Fisher's exact test was used to evaluate the association between protein expression and the patient clinicopathological parameters. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional and hazard regression analyses were performed to estimate the crude hazard ratios (HRs), adjusted HRs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of HRs. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Patient characteristics

Based on the morphological type of melanoma, there were 48 cases of superficial melanoma, 27 cases of nodular melanoma and 9 cases of lentigomaligna. Of all the melanoma cases analyzed, 26 had melanoma depths of ≤1 mm and 42 cases had depths of invasion >1 mm, while 32 cases were non-invasive. Of the 68 melanoma cases ranging from pathological stages pT1-pT4, 22 were ulcerated. In 77% of the cases, the tumor was diagnosed in sun-exposed areas (Table I).

Table I.

Association between FBXW7 protein expression and clinicopathological variables.

| FBXW7 expression, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinicopathological variables | N | High | Low | P-value |

| All cases | 100 | 53 (53.0) | 47 (47.0) | – |

| Sex | 0.41 | |||

| Male | 39 | 23 (54.8) | 16 (45.2) | |

| Female | 61 | 30 (49.2) | 31 (50.8) | |

| Age, years | 0.69 | |||

| ≤58 | 44 | 25 (56.8) | 19 (43.2) | |

| >58 | 56 | 28 (50.0) | 28 (50.0) | |

| pT stage | 0.001a | |||

| Dysplastic nevi | 16 | 15 (93.7) | 1 (6.25) | |

| pTis | 16 | 14 (73.7) | 2 (12.5) | |

| pT1 | 17 | 15 (88.2) | 2 (11.8) | |

| pT2 | 17 | 6 (35.3) | 11(64.7) | |

| pT3 | 17 | 1 (5.9) | 16 (94.1) | |

| pT4 | 17 | 2 (11.8) | 15 (88.2) | |

| Depth of invasion, mm | 0.001a | |||

| ≤1 | 26 | 20 (76.9) | 6 (23.1) | |

| >1 | 42 | 4 (9.5) | 38 (90.5) | |

| Non-invasive | 32 | 29 (90.6) | 3 (9.4) | |

| Morphology | 0.001a | |||

| Superficial spreading | 48 | 26 (54.2) | 22 (45.8) | |

| Lentigomaligna | 9 | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | |

| Nodular | 27 | 5 (18.5) | 22 (81.5) | |

| Dysplastic nevi | 16 | 15 (93.7) | 1 (6.5) | |

| Site | 0.54 | |||

| Sun-protected | 13 | 5 (38.5) | 8 (61.5) | |

| Sun-exposed | 77 | 42 (54.5) | 35 (45.5) | |

| Unknown | 10 | 6 (60.0) | 4 (4.0) | |

| Ulceration in melanoma (pT1-pT4) | 68 | 0.18 | ||

| Present | 22 | 5 (22.7) | 17 (77.3) | |

| Absent | 46 | 19 (41.3) | 27 (58.7) | |

P<0.001. pT, pathological tumor; FBXW7, F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7.

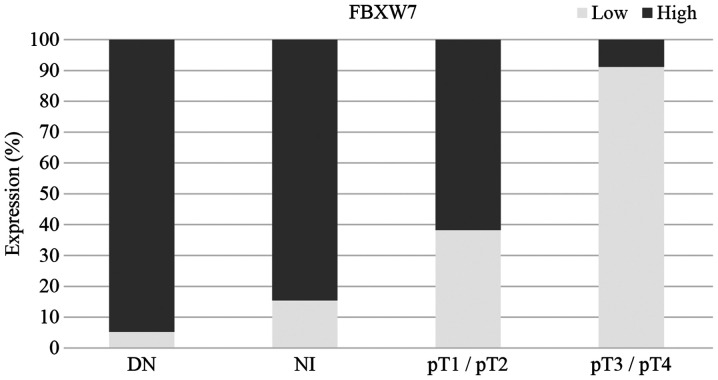

FBXW7 expression is associated with pathological stage, melanoma invasion depth and tumor morphological type

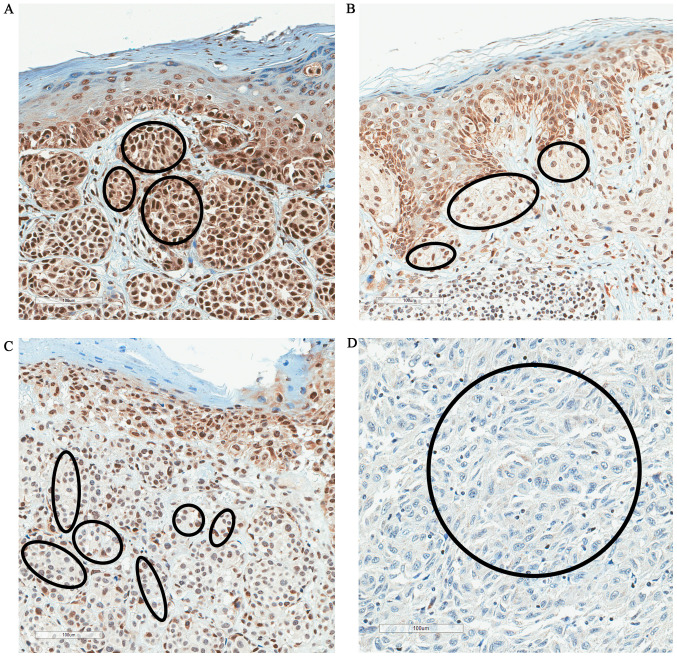

High FBXW7 expression was observed in 53% of samples, and low expression was observed in 47% of cases (Table I). There was a significant association between FBXW7 expression and pT stage. There was a significantly lower level of FBXW7 expression in advanced melanoma (pT3/pT4) compared with dysplastic nevi, melanoma in situ and pT1/pT2 stage melanoma (P<0.001; Fisher's exact test; Table I). Fig. 1 shows the proportion of high/low FBXW7 expression in dysplastic nevi, melanoma in situ, pT1/pT2 and pT3/pT4 melanoma. Fig. 2 shows the changes of immunostaining of FBXW7 protein depending on pT stage (pT1-pT4). There was strong FBXW7 immunostaining in pT1 melanoma, moderate staining in pT2, weak staining in pT3 and negative staining in pT4 melanoma (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Low FBXW7 expression is associated with melanoma progression. DN, dysplastic nevi; NI, non-invasive melanoma/melanoma in situ; FBXW7, F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7; pT, pathological tumor stage.

Figure 2.

FBXW7 protein expression in cutaneous melanoma. Representative images of (A) strong FBXW7 immunostaining in pT1 melanoma, (B) moderate FBXW7 immunostaining in pT2 melanoma, (C) weak FBXW7 staining in pT3 melanoma and (D) negative FBXW7 staining in pT4 melanoma. Marked areas indicate FBXW7 staining in malignant melanocytes. Magnification, ×100. FBXW7, F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7; pT, pathological tumor stage.

Additionally, there was a statistically significant association between FBXW7 expression and the morphological type of the tumor (P<0.001); high FBXW7 expression was observed in 93.7% of dysplastic nevus tissues, 77.8% of lentigomaligna cases and 54.2% of cases of superficial spreading melanoma, whereas 81.5% of nodular melanomas exhibited low FBXW7 expression (Table I). Furthermore, there was a statistically significant association between FBXW7 expression and the tumor invasion (P<0.001), with a depth ≤1 mm observed in 76.9% of cases with high FBXW7 expression, whereas 90.5% of cases with melanoma invasion >1 mm exhibited low FBXW7 expression (Table I). There was no statistically significant association between FBXW7 expression and sex, age or tumor localization (Table I).

p53 expression is associated with the depth of melanoma invasion and the morphological type of the tumor

There was no statistically significant association between p53 expression and melanoma pT stage. Almost equal proportions of high and low expression levels of p53 were observed in dysplastic nevi and melanoma in situ. Higher proportions of high p53 expression were observed in stage pT1/pT2 and pT3/pT4 melanoma samples compared with high p53 expression in dysplastic nevi and melanoma in situ tissues (Fig. 3). High p53 expression was observed in 70–80% of melanoma samples ranging from stage pT1 to pT4, but p53 expression was not associated with pT stage (P=0.06; Table II). Fig. 4 shows the immunostaining of p53 protein in different pT melanoma stages (pT1-pT4). Additionally, there was no association between p53 expression with sex, age and tumor localization.

Figure 3.

p53 expression in DN, NI, pT1/pT2 and pT3/pT4 melanoma. DN, dysplastic nevi; NI, non-invasive melanoma/melanoma in situ; pT, pathological tumor stage.

Table II.

Association between p53 protein expression and clinicopathological variables.

| p53 expression, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinicopathological variables | N | High | Low | P-value |

| All cases | 100 | 53 (53.0) | 47 (47.0) | – |

| Sex | 0.20 | |||

| Male | 39 | 23 (59.0) | 16 (41.0) | |

| Female | 61 | 44 (72.1) | 17 (27.9) | |

| Age, years | 0.52 | |||

| ≤58 | 44 | 31 (70.5) | 13 (29.5) | |

| >58 | 56 | 36 (64.3) | 20 (35.7) | |

| pT stage | 0.06 | |||

| Dysplastic nevi | 16 | 8 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | |

| pTis | 16 | 7 (43.7) | 9 (56.3) | |

| pT1 | 17 | 14 (82.3) | 3 (17.7) | |

| pT2 | 17 | 12 (70.6) | 5 (29.4) | |

| pT3 | 17 | 12 (70.6) | 5 (29.4) | |

| pT4 | 17 | 14 (82.3) | 3 (17.7) | |

| Depth of invasion, mm | 0.02a | |||

| ≤1 | 26 | 20 (76.9) | 6 (23.1) | |

| >1 | 42 | 32 (76.2) | 10 (23.8) | |

| Non-invasive | 32 | 15 (46.9) | 17 (53.1) | |

| Morphology | 0.01a | |||

| Superficial spreading | 48 | 33 (68.8) | 15 (31.2) | |

| Lentigomaligna | 9 | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) | |

| Nodular | 27 | 23 (85.2) | 4 (14.8) | |

| Dysplastic nevi | 16 | 8 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | |

| Site | 0.35 | |||

| Sun-protected | 13 | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) | |

| Sun-exposed | 77 | 49 (63.6) | 28 (36.4) | |

| Unknown | 10 | 7 (70.0) | 3 (30.0) | |

P<0.02. pT, pathological tumor.

Figure 4.

p53 protein expression in cutaneous melanoma. Representative images of (A) moderate p53 immunostaining in pT1 melanoma and (B) in pT2 melanoma, and (C) strong p53 immunostaining in pT3 and (D) in pT4 melanoma. Marked areas indicate p53 staining in malignant melanocytes. Magnification, ×100. pT, pathological tumor stage.

There was a statistically significant association between p53 expression and depth of melanoma invasion (P=0.02); when melanoma depth was ≤1 and >1 mm, high p53 expression was observed in 76.9 and 76.2% of cases, respectively, whereas a low p53 protein expression was detected in 53.1% of non-invasive tumors (Table II). There was also a statistically significant association between p53 expression and the morphological type of the tumor (P=0.01), with high p53 expression observed in 85.2% of nodular melanomas and in 68.8% of superficial spreading melanomas, while p53 expression in lentigomaligna tissues was mainly low (Table II).

c-Myc protein expression is not associated with advanced melanoma

Examination of c-Myc protein expression (Fig. 5) revealed that its expression was high in 36% of cases and low in 64% of cases. c-Myc protein expression was not significantly associated with advanced melanoma. Similarly, c-Myc expression was not associated with any clinicopathological parameters, including sex, age, morphological type of the tumor, depth of invasion and localization (Table III).

Figure 5.

c-Myc protein expression in cutaneous melanoma. Representative images of (A) high c-Mycimmunostaining in pT1 melanoma, (B) moderate c-Mycimmunostainingin pT2 melanoma and (C) in pT3 melanoma, and (D) weak c-Mycimmunostaining in pT4 melanoma. Marked areas indicate c-Myc staining in malignant melanocytes. Magnification, ×100. pT, pathological tumor stage.

Table III.

Association between c-Myc protein expression and clinicopathological variables.

| c-Myc expression, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinicopathological variables | N | High | Low | P-value |

| All cases | 100 | 36 (36.0) | 64 (64.0) | – |

| Sex | 0.29 | |||

| Male | 39 | 17 (43.6) | 22 (56.4) | |

| Female | 61 | 19 (31.1) | 42 (68.9) | |

| Age, years | 0.53 | |||

| ≤58 | 44 | 14 (31.8) | 30 (68.2) | |

| >58 | 56 | 22 (39.3) | 34 (60.7) | |

| pT stage | 0.75 | |||

| Dysplastic nevus | 16 | 8 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | |

| pTis | 16 | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) | |

| pT1 | 17 | 7 (41.2) | 10 (58.8) | |

| pT2 | 17 | 5 (29.4) | 12 (70.6) | |

| pT3 | 17 | 5 (29.4) | 12 (70.6) | |

| pT4 | 17 | 5 (29.4) | 12 (70.6) | |

| Depth of invasion, mm | 0.37 | |||

| ≤1 | 26 | 10 (38.5) | 16 (61.5) | |

| >1 | 42 | 12 (28.6) | 30 (71.4) | |

| Non-invasive | 32 | 14 (43.7) | 18 (56.3) | |

| Morphology | 0.57 | |||

| Superficial spreading | 48 | 17 (35.4) | 31 (64.6) | |

| Lentigomaligna | 9 | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) | |

| Nodular | 27 | 8 (29.6) | 19 (70.4) | |

| Dysplastic nevus | 16 | 8 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | |

| Site | 0.59 | |||

| Sun-protected | 13 | 5 (38.5) | 8 (61.5) | |

| Sun-exposed | 77 | 29 (37.7) | 48 (62.3) | |

| Unknown | 10 | 2 (20.0) | 8 (80.0) | |

pT, pathological tumor.

Decreased c-Myc expression was observed in 56% of melanoma cases, and in 71.4% of these cases, decreased expression was observed at melanoma depths >1 mm. There were no changes in c-Myc expression in dysplastic nevus, as both increased and decreased expression was observed in 50% of cases. There was a slight decrease in c-Myc expression observed in cases with melanoma in situ and stage pT1 melanoma, and low c-Myc protein expression levels were observed in 70.6% of melanoma cases in stages pT2, pT3 and pT4. However, there was no statistically significant association between c-Myc expression levels and the pathological stage of melanoma (P=0.75).

MDM2 expression levels are not associated with advanced melanoma

The present study revealed that there was low MDM2 expression in 97% of all investigated tumor samples; therefore, MDM2 expression did not exhibit any statistically significant association with advanced melanoma or any other clinicopathological parameters (Table IV and Fig. 6).

Table IV.

Association between MDM2 protein expression and clinicopathological variables.

| MDM2 expression, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinicopathological variables | N | High | Low | P-value |

| All cases | 100 | 3 (3.0) | 97 (97.0) | – |

| Sex | 0.56 | |||

| Male | 39 | 2 (5.1) | 37 (94.9) | |

| Female | 61 | 1 (1.1) | 60 (98.9) | |

| Age, years | 0.58 | |||

| ≤58 | 44 | 2 (4.5) | 42 (95.5) | |

| >58 | 56 | 1 (1.8) | 55 (98.2) | |

| pT stage | 0.99 | |||

| Dysplastic nevus | 16 | 0 (0.0) | 16 (100.0) | |

| pTis | 16 | 1 (6.3) | 15 (93.7) | |

| pT1 | 17 | 1 (5.9) | 16 (94.1) | |

| pT2 | 17 | 0 (0.0) | 17 (100.0) | |

| pT3 | 17 | 1 (5.9) | 16 (94.1) | |

| pT4 | 17 | 0 (0.0) | 17 (100.0) | |

| Depth of invasion, mm | 0.99 | |||

| ≤1 | 26 | 1 (3.8) | 25 (96.2) | |

| >1 | 42 | 1 (2.4) | 41 (97.6) | |

| Non-invasive | 32 | 1 (3.1) | 31 (96.9) | |

| Morphology | 0.34 | |||

| Superficial spreading | 48 | 1 (2.1) | 47 (97.9) | |

| Lentigomaligna | 9 | 1 (11.1) | 8 (88.9) | |

| Nodular | 27 | 1 (3.7) | 26 (96.3) | |

| Dysplastic nevus | 16 | 0 (0.0) | 16 (100.0) | |

| Site | 0.99 | |||

| Sun-protected | 13 | 0 (0.0) | 13 (100.0) | |

| Sun-exposed | 77 | 3 (3.9) | 74 (96.1) | |

| Unknown | 10 | 0 (0.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

pT, pathological tumor.

Figure 6.

MDM2 protein expression in cutaneous melanoma. Representative images of (A) weak MDM2 immunostaining in pT1 melanoma and (B) in pT2 melanoma, (C) moderate MDM2 immunostaining in pT3 melanoma and (D) weak MDM2immunostaining in pT4 melanoma. Marked areas indicate MDM2 staining in malignant melanocytes. Magnification, ×100. pT, pathological tumor stage.

FBXW7 protein expression is associated with c-Myc protein expression

Fisher's exact test was performed to evaluate the association between FBXW7, c-Myc, MDM2 and p53 expression. The results revealed that there was a statistically significant association between FBXW7 and c-Myc expression, revealing that 76.6% of cases with low FBXW7 expression had also low c-Myc expression (P=0.02; Table V). There was no other statistically significant association between protein expression.

Table V.

Association between the changes in the protein expression levels of FBXW7, c-Myc, MDM2 and p53.

| p53, n (%) | c-Myc, n (%) | MDM2, n (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins | Expression levels | High | Low | P-value | High | Low | P-value | High | Low | P-value |

| c-Myc | High | 27 (75.0) | 9 (25.0) | 0.27 | ||||||

| Low | 40 (62.5) | 24 (37.5) | ||||||||

| MDM2 | High | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0.99 | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0.29 | |||

| Low | 34 (35.0) | 36 (65.0) | 34 (35.0) | 36 (65.0) | ||||||

| FBXW7 | High | 33 (62.3) | 20 (37.7) | 0.30 | 25 (47.2) | 28 (52.8) | 0.02a | 2 (3.8) | 51 (96.2) | 0.99 |

| Low | 34 (72.3) | 13 (27.7) | 11 (23.4) | 36 (76.6) | 1 (2.1) | 46 (97.9) | ||||

P<0.02. FBXW7, F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7.

High FBXW7 expression is positively associated with survival

A univariate Cox regression analysis was used to determine which of the analyzed clinicopathological indicators may be associated with survival. The results revealed that sex, age, morphological type and the localization of tumors were not significantly associated with mortality. However, tumor ulceration was found to increase the risk of death by 2.79 times, although this rate was not statistically significant (P=0.06). Patient survival was significantly influenced by pT stage, where the risk of death increased by 5.6 times with advanced stage (P=0.03). Taking into account the impact of changes in the expression levels of FBXW7, c-Myc and p53 on the risk of death, the results revealed that high FBXW7 expression decreased the risk of death and improved survival (P=0.08), and high expression levels of p53 increased the risk of death by 2.48 times (P=0.10). However, these rates were not statistically significant. The results revealed that c-Myc expression was not significantly associated with mortality (Table VI). A multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed no statistically significant results (Table VII).

Table VI.

Univariate Cox regression analysis of protein expression and clinicopathological variables predicting the survival of patients with cutaneous melanoma.

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, males vs. females | 2.01 (0.56–7.22) | 0.29 |

| Age, ≤58 vs. >58 years | 1.16 (0.39–3.49) | 0.79 |

| pT stage, pT1/pT2 vs. pT3/pT4 | 5.60 (1.24–25.2) | 0.03a |

| Morphology, superficial spreading vs. other | 2.48 (0.83–7.43) | 0.10 |

| Ulceration, absent vs. present | 2.79 (0.95–8.08) | 0.06 |

| Site, sun-protected vs. sun-exposed | 0.57 (0.16–2.11) | 0.40 |

| p53 expression, low vs. high | 2.48 (0.83–7.43) | 0.10 |

| c-Myc expression, low vs. high | 0.36 (0.08–1.63) | 0.19 |

| FBXW7 expression, low vs. high | 0.16 (0.02–1.23) | 0.08 |

P<0.05. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; pT, pathological tumor; FBXW7, F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7.

Table VII.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of protein expression and clinicopathological variables predicting the survival of patients with cutaneous melanoma.

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, males vs. females | 1.47 (0.31–7.07) | 0.48 |

| Age, ≤58 vs. >58 years | 0.69 (0.13–3.55) | 0.66 |

| pT stage, pT1/pT2 vs. pT3/pT4 | 3.13 (0.38–25.7) | 0.29 |

| Morphology, superficial spreading vs. other | 1.37 (0.28–6.60) | 0.69 |

| Ulceration, absent vs. present | 2.33 (0.60–9.09) | 0.23 |

| Site, sun-protected vs. sun-exposed | 0.42 (0.09–1.98) | 0.27 |

| p53 expression, low vs. high | 0.65 (0.16–2.70) | 0.55 |

| c-Myc expression, low vs. high | 0.35 (0.07–1.72) | 0.19 |

| FBXW7 expression, low vs. high | 0.65 (0.05–9.12) | 0.75 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; pT, pathological tumor; FBXW7, F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7.

Discussion

FBXW7 is a tumor suppressor that controls the protein expression levels of several oncogenes, including c-Myc, Notch, Cyclin E, c-Jun, Mcl-1 and m-TOR (5,38,39). However, little is known regarding the regulation of FBXW7 in tumors. Regulation of FBXW7 expression may occur at the transcriptional or protein levels, as well as by post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation (40). p53 molecules, NUMB4, NF-κB1, microRNA-27 and microRNA-223 are known to be important in FBXW7 regulation (10).

Previous studies have revealed decreased FBXW7 activity in melanoma cells (3,9). The present study demonstrated that FBXW7 expression was lower in primary melanoma compared with dysplastic nevi. FBXW7 expression in metastatic melanoma was lower compared with in primary melanoma, and its decreased expression was associated with a less favorable 5-year survival rate (9). Furthermore, in vitro experiments have demonstrated that FBXW7 suppresses the migration of melanoma cells via the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway; therefore, suppression of FBXW7 in melanoma cells results in increased cell migration and stress fiber formation (9).

The results of the present study revealed that FBXW7 expression decreased in advanced melanoma, and a statistically significant association was found between the decrease in FBXW7 expression and the increasing pT stage of melanoma. Additionally, a trend was observed between decreased FBXW7 expression and an increased risk of death in patients, although this association was not significant.

Previous studies have demonstrated that decreased FBXW7 expression is associated with melanoma progression and the accumulation of c-Myc protein (3,9,41). c-Myc is one of the major targets of FBXW7, and c-Myc regulates the expression of >15% of the genes involved in processes of cell differentiation, proliferation, protein synthesis, metabolism and apoptosis; thus, impaired c-Myc function may underlie tumor formation (5,42). FBW7α promotes ubiquitination of Myc in proteasomes, whereas FBW7γ ubiquitinates Myc in the nucleus and thus suppresses the ability of Myc to promote cell growth (41,43–46). Therefore, a decrease in FBXW7 expression results in increased c-Myc expression (10).

In the present study, 17 cases of stage pT2 melanoma, 17 cases of stage pT3 melanoma and 17 cases of stage pT4 melanoma were examined, and low c-Myc protein expression was detected in 12 cases (70.6%) in each group. According to a comparison of these groups with melanoma in situ and stage pT1 melanoma, the changes in c-Myc protein expression were not statistically significant. In addition, there was a strong direct association observed between the changes in FBXW7 and c-Myc expression with a decrease in FBXW7 expression, and a decrease in c-Myc expression was also observed. These results differ from those of previously published studies (41,45,47). The results of the present study may be influenced by the sample size. In addition, melanoma is a heterogeneous tumor and its development and progression is affected by the interaction of multiple genes and various signaling pathways (48). In some types of cancer, c-Myc may acquire loss-of-function mutations, while in the majority of cases, c-Myc expression is upregulated (49–52). In both cases, altered c-Myc expression results in tumor formation through disrupted transcription, translation or differentiation (42,49).

One of the most important regulators of FBXW7 is p53; p53 is a major tumor suppressor protein and is frequently mutated in several types of cancer, such as breast cancer, bone and soft tissue sarcoma, brain tumor, adrenocortical carcinoma, leukemia, stomach cancer and colorectal cancer (12–17). Previous studies have demonstrated that FBXW7 is a p53-dependent tumor suppressor gene involved in tumor development (10,11). Additionally, studies have revealed that FBXW7 expression may be restored via targeting the p53 signaling pathway (10,11). The increased expression levels of wild-type p53 have been previously demonstrated in melanoma (53). However, considering the malignant nature and resistance to treatment in cases of melanoma (54,55), p53 does not appear to be effective as a tumor suppressor in melanoma. Although the mechanisms are not yet fully understood, certain p53 targets have been shown to be downregulated (56,57).

Increased expression levels of the MDM2 oncoprotein have been reported in several types of human cancer, including sarcoma, glioma, hematologic malignancies, melanoma and carcinoma, carrying the wild-type p53 allele (35,58). High levels of MDM2 are associated with a worse prognosis in several types of cancer, such as sarcoma, glioma and pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (58,59). Malignant melanoma is characterized by increased MDM2 expression (60). Rajabi et al (61) revealed that there was an association between MDM2 expression with tumor thickness and invasion in primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. In 50% of melanoma cases, strong MDM2 expression is detected, leading to enhanced degradation of p53, and thus resulting in tumor cell proliferation (56,60,62).

In the present study, upregulated p53 expression was observed in primary and invasive melanoma. In cases of melanoma with a thickness >1 mm, p53 expression was increased compared with in non-invasive tumors, whereas FBXW7 expression decreased in advanced melanoma. Previous studies have demonstrated that the first exon of FBXW7 has a p53 binding site (11,63). Additionally, decreased FBXW7 expression following genotoxic stress may be activated by p53 (6,42). However, in the present study, there was no statistically significant association between p53 expression and the changes in FBXW7 expression.

p53 and MDM2 interact and form a negative autoregulatory loop in which elevated p53 transcriptional levels activate MDM2, which in turn decreases the levels of p53 (15,30,36). The present study revealed that there was a decrease in MDM2 expression in almost all cases assessed (97%). In contrast to published studies (60–62,64), the results of the present study did not identify a significant association between MDM2 expression and melanoma invasion, and there was no association between the decrease in MDM2 expression and p53 expression.

The main limitation of the present study consists in a relatively small number of subjects in the analyzed groups, assembled according to the stage of melanoma by depth. The sample size may have influenced the results obtained and the assessment of the effect of low FBXW7 protein expression on patient survival. Future studies should continue to analyze the expression levels of E3 ubiquitin ligases in melanoma tissues, since it is important to identify new potential targets for the treatment of melanoma, as well as to evaluate their prognostic significance. Future studies should investigate the expression levels of E3 ligases and their substrates at the mRNA level, as well as other genes involved in the development of melanoma, and should evaluate their interactions, their changes in expression associated with clinical characteristics and their prognostic significance.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that FBXW7 exhibited the most statistically significant prognostic value and associations with advanced melanoma. As most of the FBXW7 substrates are oncoproteins, their degradation by FBXW7 may underlie the mechanism by which decreased FBXW7 expression results in tumor progression and may highlight these proteins as potential targets for the treatment of melanoma.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (grant no. ESFA Nr.09.3.3-V-711-01-0001) and the project ‘Development of doctoral studies’ realization according to the 2014–2020 European Union Funds Programme of Investment Activity, priority 9 ‘Education of society and increasing of human source potential’ (grant no. ESFA-09.3.3-V-711) and ‘Support for scientific research by scientists and other researchers’.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

JM selected the patients, collected the clinicopathological data, interpreted the results and prepared the manuscript. ZG was involved in drafting and revising the manuscript, and made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data. IV performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the results and created the graphs and tables. AL was involved in performing the tissue microarray and immunohistochemical analysis, drafted and revised the manuscript. JP performed the histological examination of tissue samples of melanoma and dysplastic nevi, assisted in the tissue microarray preparation and evaluated the immunohistochemical staining. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Vilnius Regional Committee of Biomedical Research (approval no. 158200-16-878-387, approval date 2016-12-13, and addition no. 158200-878-PP1-05, 2017-03-17). All patients signed informed consent forms to participate in the present study (approval no. II-2016-5, 2016-12-07, version 4, and approval no. II-2016-5, 2017-02-14, version 5).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Morrow JK, Lin HK, Sun SC, Zhang S. Targeting ubiquitination for cancer therapies. Future Med Chem. 2015;7:2333–2350. doi: 10.4155/fmc.15.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma J, Guo W, Li C. Ubiquitination in melanoma pathogenesis and treatment. Cancer Med. 2017;6:1362–1377. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aydin IT, Melamed RD, Adams SJ, Castillo-Martin M, Demir A, Bryk D, Brunner G, Cordon-Cardo C, Osman I, Rabadan R, et al. FBXW7 mutations in melanoma and a new therapeutic paradigm. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju107. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie CM, Wei W, Sun Y. Role of SKP1-CUL1-F-box-protein (SCF) E3 ubiquitin ligases in skin cancer. J Genet Genomics. 2013;40:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welcker M, Clurman BE. FBW7 ubiquitin ligase: A tumour suppressor at the crossroads of cell division, growth and differentiation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:83–93. doi: 10.1038/nrc2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z, Inuzuka H, Zhong J, Wan L, Fukushima H, Sarkar FH, Wei W. Tumor suppressor functions of FBW7 in cancer development and progression. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:1409–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang HL, Weng HY, Wang LQ, Yu CH, Huang QJ, Zhao PP, Wen JZ, Zhou H, Qu LH. Triggering Fbw7-mediated proteasomal degradation of c-Myc by oridonin induces cell growth inhibition and apoptosis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:1155–1165. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu H, Wang K, Fu H, Song J. Low expression of the ubiquitin ligase FBXW7 correlates with poor prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2018;11:413–419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng Y, Chen G, Martinka M, Ho V, Li G. Prognostic significance of Fbw7 in human melanoma and its role in cell migration. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1794–1802. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Ye X, Liu Y, Wei W, Wang Z. Aberrant regulation of FBW7 in cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5:2000–2015. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mao JH, Perez-Losada J, Wu D, Delrosario R, Tsunematsu R, Nakayama KI, Brown K, Bryson S, Balmain A. Fbxw7/Cdc4 is a p53-dependent, haploinsufficient tumour suppressor gene. Nature. 2004;432:775–779. doi: 10.1038/nature03155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pei D, Zhang Y, Zheng J. Regulation of p53: A collaboration between Mdm2 and Mdmx. Oncotarget. 2012;3:228–235. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madan E, Gogna R, Bhatt M, Pati U, Kuppusamy P, Mahdi AA. Regulation of glucose metabolism by p53: Emerging new roles for the tumor suppressor. Oncotarget. 2011;2:948–957. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muller PAJ, Vousden KH. p53 mutations in cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:2–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wade M, Li Y, Wahl G. MDM2, MDMX and p53 in oncogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:83–96. doi: 10.1038/nrc3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olivier M, Goldgar DE, Sodha N, Ohgaki H, Kleihues P, Hainaut P, Eeles RA. Li-Fraumeni and related syndromes: Correlation between tumor type, family structure, and TP53 genotype. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6643–6650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birch JM, Alston RD, McNally RJ, Evans DG, Kelsey AM, Harris M, Eden OB, Varley JM. Relative frequency and morphology of cancers in carriers of germline TP53 mutations. Oncogene. 2001;20:4621–4628. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felsher DW, Bishop JM. Reversible tumorigenesis by MYC in hematopoietic lineages. Mol Cell. 1999;4:199–207. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80367-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marinkovic D, Marinkovic T, Mahr B, Hess J, Wirth T. Reversible lymphomagenesis in conditionally c-MYC expressing mice. Int J Cancer. 2004;110:336–342. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain M, Arvanitis C, Chu K, Dewey W, Leonhardt E, Trinh M, Sundberg CD, Bishop JM, Felsher DW. Sustained loss of a neoplastic phenotype by brief inactivation of MYC. Science. 2002;297:102–104. doi: 10.1126/science.1071489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabay M, Li Y, Felsher DW. MYC activation is a hallmark of cancer initiation and maintenance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4:1–14. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a014241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shachaf CM, Kopelman AM, Arvanitis C, Karlsson A, Beer S, Mandl S, Bachmann MH, Borowsky AD, Ruebner B, Cardiff RD, et al. MYC inactivation uncovers pluripotent differentiation and tumour dormancy in hepatocellular cancer. Nature. 2004;431:1112–1117. doi: 10.1038/nature03043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato M, Rodriguez-Barrueco R, Yu J, Do C, Silva JM, Gautier J. MYC is a critical target of FBXW7. Oncotarget. 2015;6:3292–3305. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer N, Penn LZ. Reflecting on 25 years with MYC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:976–990. doi: 10.1038/nrc2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross DA, Wilson GD. Expression of c-myc oncoprotein represents a new prognostic marker in cutaneous melanoma. Br J Surg. 1998;85:46–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greulich KM, Utikal J, Peter RU, Krähn G. c-MYC and nodular malignant melanoma. A case report. Cancer. 2000;89:97–103. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000701)89:1<97::AID-CNCR14>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraehn GM, Utikal J, Udart M, Greulich KM, Bezold G, Kaskel P, Leiter U, Peter RU. Extra c-myc oncogene copies in high risk cutaneous malignant melanoma and melanoma metastases. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:72–79. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanzler MH, Mraz-Gernhard S. Primary cutaneous malignant melanoma and its precursor lesions: Diagnostic and therapeutic overview. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:260–276. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.116239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin X, Sun R, Zhao X, Zhu D, Zhao X, Gu Q, Dong X, Zhang D, Zhang Y, Li Y, et al. C-myc overexpression drives melanoma metastasis by promoting vasculogenic mimicry via c-myc/snail/Bax signaling. J Mol Med (Berl) 2017;95:53–67. doi: 10.1007/s00109-016-1452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nag S, Zhang X, Srivenugopal KS, Wang MH, Wang W, Zhang R. Targeting MDM2-p53 interaction for cancer therapy: Are we there yet? Curr Med Chem. 2014;21:553–574. doi: 10.2174/09298673113206660325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freedman DA, Wu L, Levine AJ. Functions of the MDM2 oncoprotein. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:96–107. doi: 10.1007/s000180050273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Momand J, Wu HH, Dasgupta G. MDM2 - master regulator of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. Gene. 2000;242:15–29. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00487-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oliner JD, Pietenpol JA, Thiagalingam S, Gyuris J, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Oncoprotein MDM2 conceals the activation domain of tumour suppressor p53. Nature. 1993;362:857–860. doi: 10.1038/362857a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Momand J, Zambetti GP, Olson DC, George D, Levine AJ. The mdm-2 oncogene product forms a complex with the p53 protein and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation. Cell. 1992;69:1237–1245. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90644-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Q, Lozano G. Molecular pathways: Targeting Mdm2 and Mdm4 in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:34–41. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vassilev LT. MDM2 inhibitors for cancer therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, Gershenwald JE, Compton CC, Hess KR, Sullivan DC, et al., editors. Springer; 2017. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th edition. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng Y, Li G. Role of the ubiquitin ligase Fbw7 in cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2012;31:75–87. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9330-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Busino L, Millman SE, Scotto L, Kyratsous CA, Basrur V, OConnor O, Hoffmann A, Elenitoba-Johnson KS, Pagano M. Fbxw7α- and GSK3-mediated degradation of p100 is a pro-survival mechanism in multiple myeloma. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:375–385. doi: 10.1038/ncb2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Min SH, Lau AW, Lee TH, Inuzuka H, Wei S, Huang P, Shaik S, Lee DY, Finn G, Balastik M, et al. Negative regulation of the stability and tumor suppressor function of Fbw7 by the Pin1 prolyl isomerase. Mol Cell. 2012;46:771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yada M, Hatakeyama S, Kamura T, Nishiyama M, Tsunematsu R, Imaki H, Ishida N, Okumura F, Nakayama K, Nakayama KI. Phosphorylation-dependent degradation of c-Myc is mediated by the F-box protein Fbw7. EMBO J. 2004;23:2116–2125. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis RJ, Welcker M, Clurman BE. Tumor suppression by the Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase: Mechanisms and opportunities. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonetti P, Davoli T, Sironi C, Amati B, Pelicci PG, Colombo E. Nucleophosmin and its AML-associated mutant regulate c-Myc turnover through Fbw7γ. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:19–26. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200711040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grim JE, Gustafson MP, Hirata RK, Hagar AC, Swanger J, Welcker M, Hwang HC, Ericsson J, Russell DW, Clurman BE. Isoform- and cell cycle-dependent substrate degradation by the Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:913–920. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200802076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Welcker M, Orian A, Grim JE, Eisenman RN, Clurman BE. A nucleolar isoform of the Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase regulates c-Myc and cell size. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1852–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Welcker M, Orian A, Jin J, Grim JE, Harper JW, Eisenman RN, Clurman BE. The Fbw7 tumor suppressor regulates glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylation-dependent c-Myc protein degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9085–9090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402770101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reavie L, Buckley SM, Loizou E, Takeishi S, Aranda-Orgilles B, Ndiaye-Lobry D, et al. Regulation of c-Myc ubiquitination controls CML initiation and progression. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niezgoda A, Niezgoda P, Czajkowski R. Novel approaches to treatment of advanced melanoma: A review on targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:85138. doi: 10.1155/2015/851387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalkat M, De Melo J, Hickman KA, Lourenco C, Redel C, Resetca D, Tamachi A, Tu WB, Penn LZ. MYC deregulation in primary human cancers. Genes (Basel) 2017;8:2–30. doi: 10.3390/genes8060151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cancer Genome Atlas Network: Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumors. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Witkiewicz AK, McMillan EA, Balaji U, Baek G, Lin WC, Mansour J, Mollaee M, Wagner KU, Koduru P, Yopp A, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of pancreatic cancer defines genetic diversity and therapeutic targets. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6744. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, corp-author. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Houben R, Hesbacher S, Schmid CP, Kauczok CS, Flohr U, Haferkamp S, Müller CS, Schrama D, Wischhusen J, Becker JC. High-level expression of wild-type p53 in melanoma cells is frequently associated with inactivity in p53 reporter gene assays. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winder M, Virós A. Mechanisms of drug resistance in melanoma. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2018;249:91–108. doi: 10.1007/164_2017_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Webster MR, Fane ME, Alicea GM, Basu S, Kossenkov AV, Marino GE, Douglass SM, Kaur A, Ecker BL, Gnanapradeepan K, et al. Paradoxical role for wild-type p53 in driving therapy resistance in melanoma. Mol Cell. 2020;77:633–644.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soengas MS, Capodieci P, Polsky D, Mora J, Esteller M, Opitz-Araya X, McCombie R, Herman JG, Gerald WL, Lazebnik YA, et al. Inactivation of the apoptosis effector Apaf-1 in malignant melanoma. Nature. 2001;409:207–211. doi: 10.1038/35051606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karst AM, Dai DL, Martinka M, Li G. PUMA expression is significantly reduced in human cutaneous melanomas. Oncogene. 2005;24:1111–1116. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Onel K, Cordon-Cardo C. MDM2 and prognosis. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun Y. E3 ubiquitin ligases as cancer targets and biomarkers. Neoplasia. 2006;8:645–654. doi: 10.1593/neo.06376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Polsky D, Bastian B, Hazan C, Melzer K, Pack J, Houghton A, Busam K, Cordon-Cardo C, Osman I. HDM2 protein overexpression, but not gene amplification, is related to tumorigenesis of cutaneous melanoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7642–7646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rajabi P, Karimian P, Heidarpour M. The relationship between MDM2 expression and tumor thickness and invasion in primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:452–455. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Polsky D, Melzer K, Hazan C, Panageas KS, Busam K, Drobnjak M, Kamino H, Spira JG, Kopf AW, Houghton A, et al. HDM2 protein overexpression and prognosis in primary malignant melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1803–1806. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.23.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kimura T, Gotoh M, Nakamura Y, Arakawa H. hCDC4b, a regulator of cyclin E, as a direct transcriptional target of p53. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:431–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Muthusamy V, Hobbs C, Nogueira C, Cordon-Cardo C, McKee PH, Chin L, Bosenberg MW. Amplification of CDK4 and MDM2 in malignant melanoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:447–454. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.