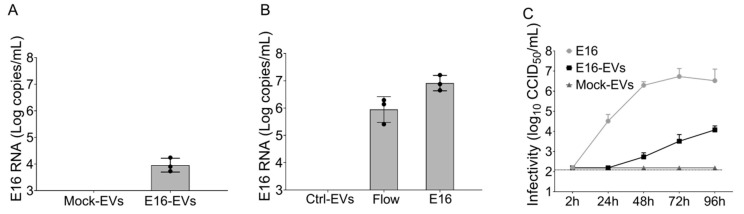

Figure 4.

EVs released from E16-infected EndoC-βH1 cells transmit productive enterovirus infection to recipient cells. (A) Real-time qPCR analysis of enterovirus RNA content in immunopurified EpCAM-positive EVs from mock (Mock-EVs) or E16-infected EndoC-βH1 cells (E16-EVs). (B) EVs derived from mock-infected EndoC-βH1 cells were exposed to free E16 and re-isolated by the immunomagnetic selection of EpCAM-positive EVs. Enterovirus RNA content was analyzed by qPCR in EpCAM-selected EVs (Control-EVs) and flow-through samples. Cell-free virus (E16) was used as a positive control. (C) Naïve EndoC-βH1 cells were incubated with EVs from E16-infected EndoC-βH1 cells (E16-EVs) or mock-infected cells (Mock-EVs). EndoC-βH1 cells infected with the cell-free virus (E16) at an MOI of 0.00001 were used as a positive control. At 2 hpi, cells were washed off, and cultured in fresh Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) medium for further 96 h. Total EndoC-βH1 cell lysates (cells plus supernatants) were collected at different time points and viral titers determined by end-point dilution on GMK cells. Dotted black lines indicate the limit of detection. Data are representative of three independent experiments, with each measurement performed in triplicate (mean ± SEM).