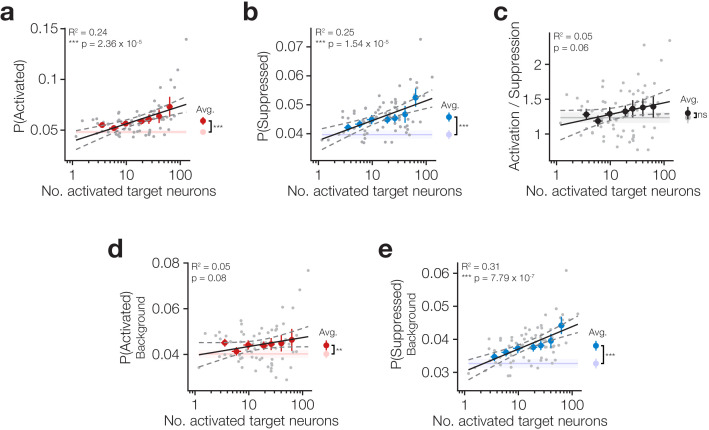

Figure 3. Increasing target activation is matched by background network suppression.

(a) The proportion of neurons activated across all neurons (targets and background) increases as more target neurons are activated. Inset right: average activation across all trial types is increased on stimulus trials compared to catch. (b) The proportion of neurons suppressed across all neurons (targets and background) increases as more target neurons are activated. Inset right: average suppression across all trial types is increased on stimulus trials compared to catch. (c) The ratio of activation and suppression is similar to that observed on catch trials (inset right) and is not strongly modulated by the number of activated target neurons. (d) Stimulation of target neurons causes mild activation of background neurons (targets excluded; inset right) but this is not modulated by the number of target neurons activated. (e) Stimulation of target neurons causes suppression of background neurons (targets excluded; inset right) which increases as more target neurons are activated. All data are hit:miss matched to remove potential lick signals (see Figure 3—figure supplement 1 and Materials and methods). For all plots N = 11 sessions, 6 mice, 1–2 sessions each. Some trial types from some sessions are excluded for having too few hits or misses to be able to match the hit:miss ratio. Error bars and shading are s.e.m; data points, error bars and linear fits are stimulus trials, shading is catch trials; grey data points: individual trial types, individual sessions; coloured error bars: data averaged within trial type (number of target zones) across sessions; linear fits are to individual data points; fits are reported ± 95% confidence intervals.