Over the course of evolution for billions of years, bacteria that are capable of light-driven energy production have occupied every corner of surface Earth where sunlight can reach. Only two general biological systems have evolved in bacteria to be capable of net energy conservation via light harvesting: one is based on the pigment of (bacterio-)chlorophyll and the other is based on proton-pumping rhodopsin. There is emerging genomic evidence that these two rather different systems can coexist in a single bacterium to take advantage of their contrasting characteristics in the number of genes involved, biosynthesis cost, ease of expression control, and efficiency of energy production and thus enhance the capability of exploiting solar energy. Our data provide the first clear-cut evidence that such dual phototrophy potentially exists in glacial bacteria. Further public genome mining suggests this understudied dual phototrophic mechanism is possibly more common than our data alone suggested.

KEYWORDS: phototrophy, glacial bacteria, bacteriochlorophyll, rhodopsin, genome evolution

ABSTRACT

Conserving additional energy from sunlight through bacteriochlorophyll (BChl)-based reaction center or proton-pumping rhodopsin is a highly successful life strategy in environmental bacteria. BChl and rhodopsin-based systems display contrasting characteristics in the size of coding operon, cost of biosynthesis, ease of expression control, and efficiency of energy production. This raises an intriguing question of whether a single bacterium has evolved the ability to perform these two types of phototrophy complementarily according to energy needs and environmental conditions. Here, we report four Tardiphaga sp. strains (Alphaproteobacteria) of monophyletic origin isolated from a high Arctic glacier in northeast Greenland (81.566° N, 16.363° W) that are at different evolutionary stages concerning phototrophy. Their >99.8% identical genomes contain footprints of horizontal operon transfer (HOT) of the complete gene clusters encoding BChl- and xanthorhodopsin (XR)-based dual phototrophy. Two strains possess only a complete XR operon, while the other two strains have both a photosynthesis gene cluster and an XR operon in their genomes. All XR operons are heavily surrounded by mobile genetic elements and are located close to a tRNA gene, strongly signaling that a HOT event of the XR operon has occurred recently. Mining public genome databases and our high Arctic glacial and soil metagenomes revealed that phylogenetically diverse bacteria have the metabolic potential of performing BChl- and rhodopsin-based dual phototrophy. Our data provide new insights on how bacteria cope with the harsh and energy-deficient environment in surface glacier, possibly by maximizing the capability of exploiting solar energy.

OBSERVATION

Over billions of years of evolution, phototrophic bacteria capable of light-driven energy generation have occupied every corner of surface Earth where solar irradiation can reach. Only two general biological systems are known in bacteria to be capable of net energy conservation from light harvesting: one is based on bacteriochlorophyll (BChl; chlorophyll in the case of Cyanobacteria) and the other is based on proton-pumping rhodopsin (1). BChl-based light harvesting relies on a complex system consisting of dozens of proteins and pigments to form reaction center and antenna complex. In contrast, the rhodopsin-based system requires only a few genes to operate, including a key pair of genes, the rhodopsin gene and the carotenoid oxygenase gene blh/brp for retinal biosynthesis (2), albeit at a much lower efficiency in energy production than the BChl-based system (3).

BChl- and rhodopsin-based systems display contrasting characteristics in the size of coding operon, cost of biosynthesis, ease of expression control, and efficiency of energy production. This raises an intriguing question of whether a single bacterium can employ both types of phototrophy to take advantage of their complementary properties in order to increase the flexibility in energy production. Given the high abundance and frequent coexistence of BChl-based phototrophs and rhodopsin-based phototrophs in the same environment, for instance, oceans (4), and given that phototrophy-related genes frequently occurred in extrachromosomal genetic elements, like photosynthesis gene cluster on plasmids (5, 6) or chromid (7) and proteorhodopsin gene in viral genomes (8), BChl- and rhodopsin-based dual phototrophic bacteria very likely have evolved in nature, awaiting discovery.

Indeed, there is emerging genomic evidence for such dual phototrophy. Recently, three Roseiflexus genomes (Chloroflexi phylum) from spring microbial mats were found to contain both pufM (encoding the M subunit of reaction center) and xanthorhodopsin (XR)-like genes (9), including two metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) of Roseiflexus spp. OTU-1 and OTU-6 (10) and one from the isolate Roseiflexus sp. RS-1 (11), albeit it is unclear whether their rhodopsins function as a bona fide proton pump, owing to the absence of the key carotenoid oxygenase gene blp/brh that is often located in the genomic neighborhood of the rhodopsin gene (10).

Discovery of glacial bacteria with potential dual phototrophy.

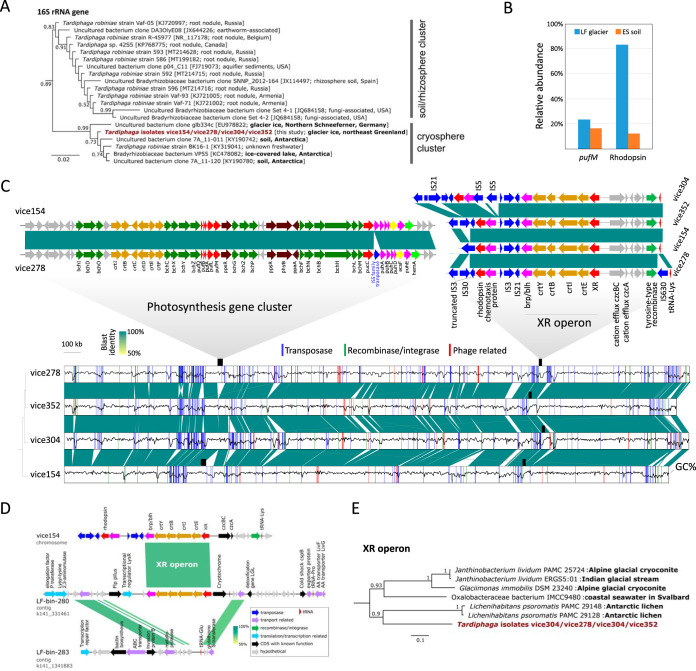

Aiming to provide further pure culture and direct evolutionary evidence for dual phototrophy, we conducted both cultivation and metagenomics survey on the microbial communities in the “Lille Firn” glacier (LF) and nearby exposed soil (ES) in northeast Greenland (81.566° N, 16.363° W; Fig. S1). A collection of isolates of aerobic phototrophic bacteria was created from the LF surface glacial ice sample. Four pinkish colonies (designated strains vice154, vice278, vice304, and vice352) were further examined due to high similarities in their profiles on the matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight mass spectrometer and due to the observation that vice154 and vice278 displayed weak BChl fluorescence signals inside the colony infrared imaging system (12). The 16S rRNA genes of these four strains are 100% identical and share 96.5% identity to Tardiphaga robiniae LMG 26467T of the genus Tardiphaga of Alphaproteobacteria (13), indicating that they represent a novel species in the cryospheric cluster of Tardiphaga (Fig. 1A). In the glacial bacterial community (LF), members of Tardiphaga accounted for 0.017% (17/101,183 reads) (Fig. S2). No Tardiphaga-affiliated read was found in ES (n = 10,060). Thus, Tardiphaga represents one of the least abundant groups and occurs only in LF.

FIG 1.

(A) Maximum-likelihood phylogeny of 16S rRNA genes. (B) Abundance of pufM and rhodopsin genes in the “Little Firn” glacier (LF) and nearby exposed soil (ES) metagenomes, calculated as the number of mapped reads normalized to per-kb gene length divided by the normalized number of reads mapped to the housekeeping gene recA. (C) Genome synteny and sequence similarities of Tardiphaga sp. strains vice154, vice278, vice304, and vice352. The GenBank accession number and source environment of each 16S rRNA gene sequence are shown in parentheses on the tree. The architecture of photosynthesis gene cluster and xanthorhodopsin (XR) operon are highlighted. Gaps in the alignment show nonconserved regions caused by mobilome-related activities, including transposase, recombinase, integrase, or phage-related genes, the locations of which are highlighted in the genome. All genomes are complete and start at the replication origin locus. The black wavy line inside each genome (shown as boxes) represents GC content calculated in a window of 1 kb. The relationship between strains was estimated as a distance-based genome tree in the bottom left using MASH (https://github.com/marbl/Mash). Color bar, BLAST identities. (D) Genome synteny between two contigs from the XR-bearing glacial Tardiphaga MAG LF-bin-280 and the nonphototrophic glacial Tardiphaga MAG LF-bin-283 in reference to the genome of strain vice154. MAG, metagenome-assembled genome. (E) Maximum-likelihood phylogeny of the whole XR operon of Tardiphaga isolates and their top tBLASTn hits in NCBI’s genome database; see Fig. S5 for the full version of the tree.

Photographs showing the sampling site, fieldwork, and visual inspection of a sampled ice block. Download FIG S1, PDF file, 1.6 MB (1.6MB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Composition of total bacterial communities in LF and ES at the phylum level (A) highlighting Alphaproteobacteria that contain the Tardiphaga genus (B). Download FIG S2, PDF file, 0.3 MB (288.6KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Despite their monophyletic origin as reflected by the genome pairwise average nucleotide identity of >99.8% and the highly conserved genome synteny (Fig. 1C), these four strains differed in both genome size and GC content (Table S1). These differences were primarily caused by insertions and deletions (Fig. 1C), including a 45.7-kb photosynthesis gene cluster that is present in vice154 and vice278 but absent in vice304 and vice352. These two photosynthesis gene clusters differ only in the insertion of an IS5 family transposase gene between pucC and puhA in vice278 (Fig. 1C). No mobilome-related genes were found in the proximity of the photosynthesis gene cluster in both vice154 and vice278 (Fig. S3), suggesting that photosynthesis gene cluster is an ancient trait in their ancestor that later was lost in vice304 and vice352.

Annotated genomic regions surrounding the photosynthesis gene cluster in Tardiphaga strains vice154 and vice278 in comparison to strains vice304 and vice352 that do not contain a photosynthesis gene cluster. Download FIG S3, PDF file, 1.5 MB (1.5MB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Summary of complete genomes of the four Tardiphaga strains isolated from the “Little Firn” glacier in northeast Greenland. Download Table S1, PDF file, 0.2 MB (162.5KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

All four genomes contain an XR operon encoding XR-based phototrophy with the same gene arrangement (XR-crtEIBY-brp) and almost 100% identical nucleotide sequences (only one base difference out of 6,257 sites occurring in vice304) (Fig. 1C). The predicted XR protein sequence contains most of the conserved sites including key residues as proton acceptor and donor (Fig. S4), suggesting that it very likely encodes a functional proton pump. Interestingly, there are an additional unclassified rhodopsin gene and a putative methyl-accepting chemotaxis gene located immediately upstream of the XR operon and flanked by insertion (IS) elements at both sides.

Protein sequence alignment showing the presence of residues in Tardiphaga’s xanthorhodopsin that are key to its function as a proton pump. Download FIG S4, PDF file, 2.4 MB (2.4MB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Maximum-likelihood phylogeny of the whole XR operon of Tardiphaga isolates and their top tBLASTn hits in NCBI’s genome database. Download FIG S5, PDF file, 0.2 MB (221.8KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

The XR operon is located near the tRNA-Lys gene in all four genomes. Bacterial tRNA genes are considered recombination hot spot region in bacterial genomes (14). Thus, the presence of multiple IS elements and a tRNA gene in the vicinity of the XR operon strongly indicates that a horizontal operon transfer (HOT) event of the XR operon has occurred in these four strains. This was further supported by reconstruction of two Tardiphaga MAGs (LF-bin-280 with an XR operon and LF-bin-283 without an XR operon; Table 1), where HOT of a complete XR operon was recorded at a highly homologous region next to the tRNA-Glu gene (Fig. 1D). Since the first discovery of proteorhodopsins in the oceans (15), there has been a growing body of phylogeny-based evidence for horizontal transfer of rhodopsin genes occurring between prokaryotes (16–18). Our data provide further clear-cut evidence for HOT of the rhodopsin gene operon occurring in a natural microbial community.

TABLE 1.

Summary of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) reconstructed from the metagenomes of the “Little Firn” glacier (LF) and nearby exposed soil (ES) that contain genes related to bacteriochlorophyll- or rhodopsin-based phototrophya

| MAG | Lineage |

Size (Mbp) |

No. of contigs |

Completeness (%) |

Contamination (%) |

Phototrophy |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Sub)phylum | Genus | pufM | PR | ActR | BR | XR | HeR | |||||

| LF-bin-79 | Alphaproteobacteria | Rubritepida | 3.78 | 585 | 95.51 | 3.73 | ● | ● | ||||

| LF-bin-280 | Alphaproteobacteria | Tardiphaga | 5.55 | 642 | 91.96 | 7.88 | ● | ● | ||||

| LF-bin-283 | Alphaproteobacteria | Tardiphaga | 4.50 | 785 | 92.36 | 8.02 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-46 | Betaproteobacteria | Ramlibacter | 4.05 | 336 | 95.48 | 4.74 | ● | ● | ||||

| LF-bin-10 | Gammaproteobacteria | n.d. | 2.55 | 141 | 92.16 | 2.56 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-172 | Gammaproteobacteria | n.d. | 3.55 | 274 | 91.13 | 0.99 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-25 | Actinobacteria | Aeromicrobium | 4.22 | 400 | 94.99 | 5.85 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-295 | Actinobacteria | Aeromicrobium | 5.01 | 519 | 100 | 7.52 | ● | ● | ||||

| LF-bin-300 | Actinobacteria | n.d. | 3.77 | 278 | 95.97 | 2.05 | ● | ● | ||||

| LF-bin-354 | Actinobacteria | n.d. | 2.42 | 100 | 96.17 | 3.64 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-355 | Bacteroidetes | Ferruginibacter | 3.68 | 394 | 91.9 | 1.07 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-258 | Bacteroidetes | Flavobacterium | 2.95 | 172 | 94.92 | 5.24 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-351 | Bacteroidetes | Flavobacterium | 3.28 | 269 | 94.16 | 3.86 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-500 | Bacteroidetes | n.d. | 2.94 | 211 | 95.95 | 0.95 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-319 | Bacteroidetes | Pedobacter | 3.00 | 296 | 90.03 | 3.99 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-240 | Bacteroidetes | Pseudopedobacter | 3.34 | 191 | 91.39 | 6.54 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-127 | Oligoflexia | Bdellovibrio | 2.86 | 186 | 91.39 | 0.9 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-439 | Oligoflexia | Bdellovibrio | 3.27 | 192 | 95.21 | 4.68 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-57 | Oligoflexia | Bdellovibrio | 2.76 | 42 | 90.32 | 0.9 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-124 | Oligoflexia | n.d. | 2.33 | 259 | 90.69 | 4.95 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-178 | Oligoflexia | n.d. | 4.04 | 82 | 91.89 | 1.79 | ● | |||||

| LF-bin-339 | Gemmatimonadetes | n.d. | 3.78 | 254 | 90.61 | 3.3 | ● | ● | ||||

| ES-bin-98 | Alphaproteobacteria | n.d. | 3.50 | 252 | 95.22 | 2.55 | ● | ● | ||||

| ES-bin-147 | Armatimonadetes | n.d. | 4.22 | 495 | 92.2 | 2.04 | ● | |||||

| ES-bin-166 | Bacteroidetes | n.d. | 4.04 | 68 | 94.46 | 0.71 | ● | |||||

| ES-bin-26 | Bacteroidetes | n.d. | 5.43 | 717 | 90.76 | 1.36 | ● | |||||

| ES-bin-22 | Cyanobacteria | Leptolyngbya | 5.12 | 603 | 91.39 | 3.97 | ● | |||||

| ES-bin-313 | Cyanobacteria | n.d. | 4.25 | 198 | 95.73 | 4.56 | ● | |||||

Only MAGs that are >90% complete with <10% contamination are shown. See Table S2 for the full list of MAGs (>50% complete and <10% contamination). PR, proteorhodopsin; XR, xanthorhodopsin; ActR, actinorhodopsin; BR, bacteriorhodopsin; HeR, heliorhodopsin (a recently discovered new type of rhodopsin [26]); n.d., not determined. The classification of rhodopsin genes was based on phylogenetic analysis using a comprehensive collection of rhodopsin genes as the reference data set (see Text S1).

Detailed materials and methods with a note on the negative results from cultivation of Tardiphaga stains in liquid media and colony pigment analysis. Download Text S1, DOCX file, 0.03 MB (29.6KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Summary of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from the LF and ES metagenomes. Download Table S2, XLSX file, 0.05 MB (50.2KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

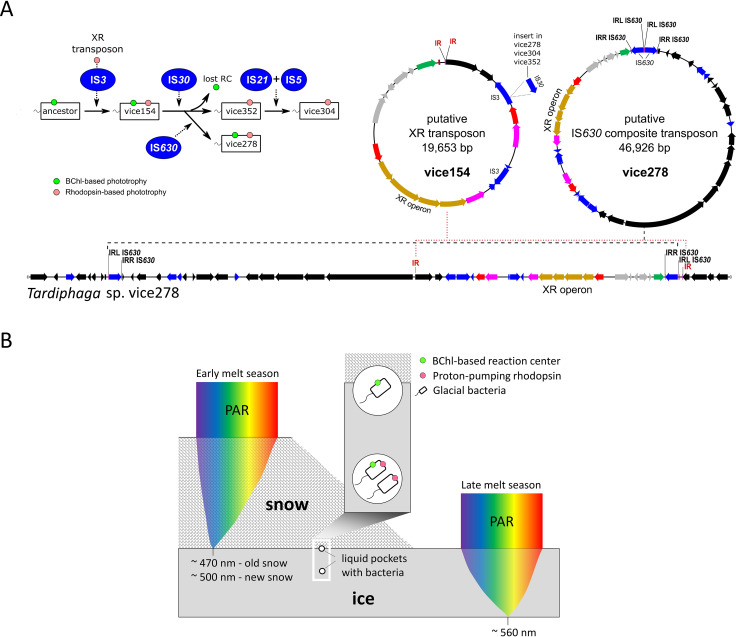

In our Tardiphaga strains, HOT of the XR operon was likely driven by transposon activities as indicated by the presence of an integrase gene (tyrosine-type recombinase family) and direct or inverted repeats in adjacent genomic regions of the integrase gene. These repeats can serve as attachment sites of the recombinase located on the predicted XR transposon and IS630 composite transposon (Fig. 2A). The putative XR transposon is conserved and thus may occur in all Tardiphaga strains. Strain vice278 possesses an additional IS630 family transposase between the XR operon and the tRNA-Lys gene, an identical copy of which is located 45.7 kb apart upstream of the XR operon (Fig. 2A). These two identical IS630 genes can serve as inverted repeats for the formation of the putative IS630 composite transposon. Given that the nucleotide sequences of the whole XR operon in these four Tardiphaga genomes are almost 100% identical, the acquisition of an XR operon in their ancestor certainly occurred before the divergence of photosynthesis gene cluster.

FIG 2.

(A) Hypothetical evolutionary path of the Tardiphaga isolates from their common ancestor based on the IS insertion patterns (left) and two transposons proposed to drive the movement of the xanthorhodopsin (XR) operon (right). The genomic region surrounding the XR operon in Tardiphaga strain vice278 was shown to highlight the distribution of direct or inverted repeats that are required to form the putative transposons. RC, reaction center; IR, inverted repeat; DR, direct repeat, IRL, inverted repeat-left; IRR, inverted repeat-right. (B) A model for light availability in snow and ice and hypothesized niche partitioning of BChl- and rhodopsin-based dual phototrophy versus only BChl- or rhodopsin-based single phototrophy. The snowpack and icepack are depicted to be of such an ideal thickness that the light spectrum with the lowest extinction coefficient reaches the exact bottom of snowpack or icepack. PAR, photosynthetically active radiation. Note that new and old snows have different spectral distribution for PAR.

Ecological importance and wide distribution of potential dual phototrophs.

Glaciers and ice sheets cover 10% of the land surface of the Earth, hosting an enormous diversity of microbes (19), among which light-driven metabolisms in BChl-based anoxygenic phototrophs have been proposed to have the potential of significantly influencing glacial carbon flux (20). BChl- and rhodopsin-based dual phototrophy can theoretically further reduce the consumption of organic matter for energy production in glacial bacteria by increasing the flexibility and efficiency in conserving light energy. Such dual phototrophy, if proved to function in situ in glacial microbial communities, could amplify the ecological importance of anoxygenic phototrophs in the glacial ecosystem.

We assessed the abundance of BChl-based phototrophs and rhodopsin-based phototrophs by targeting pufM and rhodopsin genes in the metagenomes of ES and LF. BChl-based phototrophs in both samples were comparable with LF showing a slightly higher abundance (23.3%) (Fig. 1B). However, rhodopsin-based phototrophs were almost 7-fold more abundant in LF than in ES (83.3% versus 12.2%, Fig. 1B), suggesting that rhodopsin-based phototrophs may play a more important role in supraglacial environments than BChl-based phototrophs, in line with the fact that rhodopsin-based phototrophy requires less energy and fewer components for assembly and thus probably responds faster to environmental changes than BChl-based phototrophy.

Dual phototrophy can be particularly advantageous in an extreme environment like the high Arctic glacial surface where phototrophic bacteria may have to exploit all available solar radiation for energy production. Given the advantage of dual phototrophy over single phototrophy in light harvesting, it is unclear why photosynthesis gene cluster was selectively lost in Tardiphaga sp. strains vice304 and vice352. We proposed two theories to explain this phenomenon, i.e., niche differentiation and gene mutation.

XR has maximum absorption in green light (9), while BChl and accessory carotenoids in anoxygenic phototrophs mostly absorb blue and infrared light (21). Different light wavelengths are attenuated differently through snow and ice. Under an ideal condition without impurities, gaps, and spatial heterogeneities occurring in snow and ice, blue light tends to reach the deepest into snow (22, 23), while green light at approximately 560 nm has the lowest attenuation coefficient within ice (24). Thus, different niches exist in glacial surface in terms of light intensity and quality, which may select for phototrophic bacteria with different preferences for light spectra (Fig. 2B). The loss of BChl-based phototrophy may also occur through random mutations in key photosynthetic genes, caused by, for instance, the activities of transposases, as we observed inside the photosynthesis gene cluster of strain vice278 (Fig. 1C).

There are nine MAGs reconstructed in this study that contain both pufM and rhodopsin genes (Table 1 and Table S2), including five from Alphaproteobacteria, three from Gammaproteobacteria, and one from Gemmatimonadetes, among which all but one were recovered from the LF glacier sample. To test if dual phototrophy is exclusively occurring in supraglacial environments, we further searched public databases (NCBI and ENA, n = 215,874; see Text S1) for bacterial genomes of similar dual phototrophy potential (BChl-based reaction center and proton-pumping rhodopsin). We found 3,442 XR/proteorhodopsin-like and 1,521 pufM-like tBLASTn hits (Table S3). Fifty-five genomes were predicted to contain both pufM and rhodopsin genes (Table S3) with the majority (n = 40) belonging to Alphaproteobacteria. Interestingly, there are also four Chloroflexi, three Bacteroidetes, two Deltaproteobacteria, two Gammaproteobacteria, and one Actinobacteria genome. Given the quality concern on the incomplete genomes deposited into public databases (25), it is unclear whether there is any composite among these genomes, especially those from Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria, where BChl-based phototrophy has not yet been reported. The isolation sources of these genomes cover various environments (Table S3), including freshwater, seawater, groundwater, hot spring, microbial mat/biofilm, soil, sediment, plant surface, and cryosphere (alpine/polar; n = 24), indicating that dual phototrophy is likely present in a wide range of bacteria and in a large variety of natural environments beyond glaciers.

Survey of pufM and rhodopsin genes in the genomes deposited into NCBI’s Microbial Genome and ENA’s WGS databases and the list of public genomes containing both pufM-like and rhodopsin-like genes. Download Table S3, XLSX file, 0.8 MB (834.5KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Dual phototrophy is clearly not a metabolic trait that evolved only in glacial bacteria, albeit the four glacial Tardiphaga strains in this study and their XR operons both show cryospheric origins (Fig. 1E). We investigated whether these Tardiphaga strains have other metabolic traits that may enable them to adapt to the high Arctic glacial environment. Strikingly, all four genomes contain RuBisCO genes, a phosphoribulokinase gene, and a soluble methane monooxygenase gene (Table S4), pointing to the metabolic potentials of photoautotrophy and methanotrophy. We have so far failed to grow these Tardiphaga strains in liquid media and observed the expression of neither BChl nor XR under the tested laboratory growth conditions (Text S1). Further growth optimization and physiological data are warranted to verify their dual phototrophy and other metabolic potentials and to understand how these two types of phototrophy coordinate in their metabolic networks.

Survey of key functional genes with biogeochemical or energetic importance in the genomes of Tardiphaga isolates. The gene list was compiled from the FunGen pipeline (http://fungene.cme.msu.edu/) and the authors’ own collection. Download Table S4, PDF file, 0.4 MB (361.3KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Materials and methods are available as supplemental material in Text S1.

Sequence data availability.

Genomes, metagenomes, and raw reads were deposited into GenBank under BioProject numbers PRJNA548505 and PRJNA552582.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jørgen Skafte for his excellent technical assistance at the Villum Research Station, Alexandre M. Anesio for discussion, and Niels Bohse Hendriksen for the help during the early stage of this project. We also thank Nupur and Michal Koblížek for their help on our failed experiment of pigment analysis.

This work was supported by the Villum Experiment grants no. 17601 and 32832 and a Marie Skłodowska-Curie AIAS-COFUND fellowship (EU-FP7, no. 609033) to Y.Z. The computing time and cost for the bioinformatic analysis in this work were partly supported by Computerome.dk through a fund provided by the Danish e-Infrastructure Cooperation.

Y.Z. conceived the study and wrote the paper. Y.Z., X.C., A.M.M., A.Z., L.C.L.-H., Y.L., and L.H.H. contributed to data collection or analysis. T.K.N. analyzed the mobile genetic elements. A.-S.A. conducted the classification of rhodopsin sequences. All authors read, commented on, and approved the paper.

X.C. is currently employed at BGI Europe A/S, Denmark. The employer did not play a role in the design and practice of this study and did not influence the writing of this paper in any form. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Citation Zeng Y, Chen X, Madsen AM, Zervas A, Nielsen TK, Andrei A-S, Lund-Hansen LC, Liu Y, Hansen LH. 2020. Potential rhodopsin- and bacteriochlorophyll-based dual phototrophy in a high Arctic glacier. mBio 11:e02641-20. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.02641-20.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pinhassi J, DeLong EF, Béjà O, González JM, Pedrós-Alió C. 2016. Marine bacterial and archaeal ion-pumping rhodopsins: genetic diversity, physiology, and ecology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 80:929–954. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00003-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sabehi G, Loy A, Jung KH, Partha R, Spudich JL, Isaacson T, Hirschberg J, Wagner M, Béja O. 2005. New insights into metabolic properties of marine bacteria encoding proteorhodopsins. PLoS Biol 3:e273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirchman DL, Hanson TE. 2013. Bioenergetics of photoheterotrophic bacteria in the oceans. Environ Microbiol Rep 5:188–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2012.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gómez-Consarnau L, Raven JA, Levine NM, Cutter LS, Wang D, Seegers B, Arístegui J, Fuhrman JA, Gasol JM, Sañudo-Wilhelmy SA. 2019. Microbial rhodopsins are major contributors to the solar energy captured in the sea. Sci Adv 5:eaaw8855. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw8855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen J, Brinkmann H, Bunk B, Michael V, Päuker O, Pradella S. 2012. Think pink: photosynthesis, plasmids and the Roseobacter clade. Environ Microbiol 14:2661–2672. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinkmann H, Göker M, Koblížek M, Wagner-Döbler I, Petersen J. 2018. Horizontal operon transfer, plasmids, and the evolution of photosynthesis in Rhodobacteraceae. ISME J 12:1994–2010. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0150-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Zheng Q, Lin W, Jiao N. 2019. Characteristics and evolutionary analysis of photosynthetic gene clusters on extrachromosomal replicons: from streamlined plasmids to chromids. mSystems 4:e00358-19. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00358-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yutin N, Koonin EV. 2012. Proteorhodopsin genes in giant viruses. Biol Direct 7:34. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-7-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balashov SP, Imasheva ES, Boichenko VA, Antón J, Wang JM, Lanyi JK. 2005. Xanthorhodopsin: a proton pump with a light-harvesting carotenoid antenna. Science 309:2061–2064. doi: 10.1126/science.1118046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thiel V, Hügler M, Ward DM, Bryant DA. 2017. The dark side of the mushroom spring microbial mat: life in the shadow of chlorophototrophs. II. Metabolic functions of abundant community members predicted from metagenomic analyses. Front Microbiol 8:943. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tank M, Thiel V, Ward DM, Bryant DA. 2017. A panoply of phototrophs: an overview of the thermophilic chlorophototrophs of the microbial mats of alkaline siliceous hot springs in Yellowstone National Park, WY, USA, p 87–137. In Hallenbeck PC (ed), Modern topics in the phototrophic prokaryotes. Springer, Cham, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng Y, Feng F, Medova H, Dean J, Kobli Ek M. 2014. Functional type 2 photosynthetic reaction centers found in the rare bacterial phylum Gemmatimonadetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:7795–7800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400295111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Meyer SE, Coorevits A, Willems A. 2012. Tardiphaga robiniae gen. nov., sp. nov., a new genus in the family Bradyrhizobiaceae isolated from Robinia pseudoacacia in Flanders (Belgium). Syst Appl Microbiol 35:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyd EF, Almagro-Moreno S, Parent MA. 2009. Genomic islands are dynamic, ancient integrative elements in bacterial evolution. Trends Microbiol 17:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Béja O, Aravind L, Koonin EV, Suzuki MT, Hadd A, Nguyen LP, Jovanovich SB, Gates CM, Feldman RA, Spudich JL, Spudich EN, DeLong EF. 2000. Bacterial rhodopsin: evidence for a new type of phototrophy in the sea. Science 289:1902–1906. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5486.1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frigaard NU, Martinez A, Mincer TJ, DeLong EF. 2006. Proteorhodopsin lateral gene transfer between marine planktonic Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 439:847–850. doi: 10.1038/nature04435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ugalde JA, Podell S, Narasingarao P, Allen EE. 2011. Xenorhodopsins, an enigmatic new class of microbial rhodopsins horizontally transferred between archaea and bacteria. Biol Direct 6:52. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-6-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward LM, Hemp J, Shih PM, McGlynn SE, Fischer WW. 2018. Evolution of phototrophy in the Chloroflexi phylum driven by horizontal gene transfer. Front Microbiol 9:260. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anesio AM, Laybourn-Parry J. 2012. Glaciers and ice sheets as a biome. Trends Ecol Evol 27:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franzetti A, Tagliaferri I, Gandolfi I, Bestetti G, Minora U, Mayer C, Azzoni RS, Diolaiuti G, Smiraglia C, Ambrosini R. 2016. Light-dependent microbial metabolisms drive carbon fluxes on glacier surfaces. ISME J 10:2984–2988. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stomp M, Huisman J, Stal LJ, Matthijs HC. 2007. Colorful niches of phototrophic microorganisms shaped by vibrations of the water molecule. ISME J 1:271–282. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grenfell TC, Maykut GA. 1977. The optical properties of ice and snow in the Arctic Basin. J Glaciol 18:445–463. doi: 10.1017/S0022143000021122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hancke K, Lund-Hansen LC, Lamare ML, Højlund Pedersen S, King MD, Andersen P, Sorrell BK. 2018. Extreme low light requirement for algae growth underneath sea ice: a case study from Station Nord, NE Greenland. J Geophys Res Oceans 123:985–1000. doi: 10.1002/2017JC013263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perovich DK, Roesler CS, Pegau WS. 1998. Variability in Arctic sea ice optical properties. J Geophys Res 103:1193–1208. doi: 10.1029/97JC01614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaiber A, Eren AM. 2019. Composite metagenome-assembled genomes reduce the quality of public genome repositories. mBio 10:e00725-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00725-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pushkarev A, Inoue K, Larom S, Flores-Uribe J, Singh M, Konno M, Tomida S, Ito S, Nakamura R, Tsunoda SP, Philosof A, Sharon I, Yutin N, Koonin EV, Kandori H, Béjà O. 2018. A distinct abundant group of microbial rhodopsins discovered using functional metagenomics. Nature 558:595–599. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0225-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Photographs showing the sampling site, fieldwork, and visual inspection of a sampled ice block. Download FIG S1, PDF file, 1.6 MB (1.6MB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Composition of total bacterial communities in LF and ES at the phylum level (A) highlighting Alphaproteobacteria that contain the Tardiphaga genus (B). Download FIG S2, PDF file, 0.3 MB (288.6KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Annotated genomic regions surrounding the photosynthesis gene cluster in Tardiphaga strains vice154 and vice278 in comparison to strains vice304 and vice352 that do not contain a photosynthesis gene cluster. Download FIG S3, PDF file, 1.5 MB (1.5MB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Summary of complete genomes of the four Tardiphaga strains isolated from the “Little Firn” glacier in northeast Greenland. Download Table S1, PDF file, 0.2 MB (162.5KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Protein sequence alignment showing the presence of residues in Tardiphaga’s xanthorhodopsin that are key to its function as a proton pump. Download FIG S4, PDF file, 2.4 MB (2.4MB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Maximum-likelihood phylogeny of the whole XR operon of Tardiphaga isolates and their top tBLASTn hits in NCBI’s genome database. Download FIG S5, PDF file, 0.2 MB (221.8KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Detailed materials and methods with a note on the negative results from cultivation of Tardiphaga stains in liquid media and colony pigment analysis. Download Text S1, DOCX file, 0.03 MB (29.6KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Summary of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from the LF and ES metagenomes. Download Table S2, XLSX file, 0.05 MB (50.2KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Survey of pufM and rhodopsin genes in the genomes deposited into NCBI’s Microbial Genome and ENA’s WGS databases and the list of public genomes containing both pufM-like and rhodopsin-like genes. Download Table S3, XLSX file, 0.8 MB (834.5KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Survey of key functional genes with biogeochemical or energetic importance in the genomes of Tardiphaga isolates. The gene list was compiled from the FunGen pipeline (http://fungene.cme.msu.edu/) and the authors’ own collection. Download Table S4, PDF file, 0.4 MB (361.3KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Zeng et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.