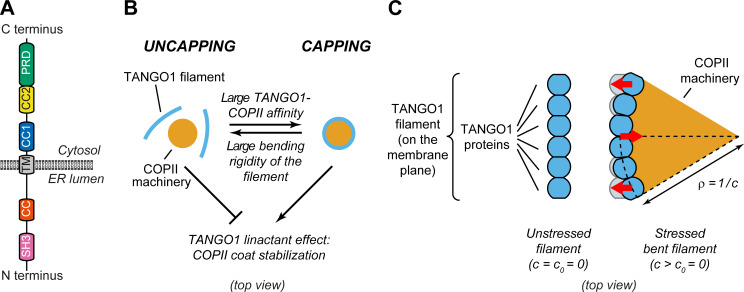

Figure 1. Physical model of TANGO1 ring formation.

(A) Schematic representation of the domain structure and topology of TANGO1, indicating the SH3 domain, a lumenal coiled-coiled domain (CC), the one and a half transmembrane region (TM), the coiled-coiled 1 (CC1) and 2 (CC2) domains, and the PRD. (B) Schematic description of the TANGO1 ring formation model (top view). ERES consisting of COPII subunits assemble into in-plane circular lattices (orange), whereas proteins of the TANGO1 family assemble into filaments by lateral protein-protein interactions (light blue). The competition between the affinity of the TANGO1 filament to bind COPII subunits (promoting capping of peripheral COPII subunits) and the resistance of the filament to be bent (promoting uncapping) controls the capping-uncapping transition. Only when TANGO1 caps the COPII lattice, it acts as a linactant by stabilizing the peripheral COPII subunits. (C) Schematic representation of individual proteins that constitute a TANGO1 filament and of how filament bending is associated with elastic stress generation. Individual TANGO1 family proteins (blue shapes) bind each other in a way that is controlled by the structure of protein-protein binding interfaces, leading to formation of an unstressed filament of a certain preferred curvature, (left cartoon, showing the case where = 0). Filament bending can be caused by the capping of TANGO1 filament to peripheral COPII machinery (orange area), which generates a stressed bent filament of a certain radius of curvature, (right cartoon). Such deviations from the preferred shape (shown in light blue) are associated with elastic stress generation (red arrows point to the direction of the generated bending torque, which correspond to the direction of recovery of the filament preferred shape).