Abstract

Brusatol, a quassinoid natural product, is effective against multiple diseases including hematologic malignancies, as we reported recently by targeting the PI3Kγ isoform, but toxicity limits its further development. Herein, we report the synthesis of a series of conjugates of brusatol with amino acids and short peptides at its enolic hydroxyl at C-3. A number of conjugates with smaller amino acids and peptides demonstrated activities comparable to brusatol. Through in vitro and in vivo evaluations, we identified UPB-26, a conjugate of brusatol with a L-β-homoalanine, which exhibits good chemical stability at physiological pH’s (SGF and SIF), moderate rate of conversion to brusatol in both human and rat plasmas, improved mouse liver microsomal stability, and most encouragingly, enhanced safety compared to brusatol in mice upon IP administration.

Keywords: Brusatol, Conjugates, Prodrugs, Toxicity

Nature has long been an important resource for biomedical scientists in searching for potential therapeutic drugs and in the development of ideas for lead compounds, by providing an abundance of natural products with diverse and novel structures.1–4 However, it is well recognized that some of these natural products, despite being potent towards their targets, possess undesired adverse effects when used at therapeutic doses. Many natural products also have low efficacies due to unfavorable absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion (ADME), and pharmacokinetic profiles, which hinder their development for clinical use.5,6 To tackle these less than perfect yet inspiring scaffolds and improve their druggable properties, chemical modifications have been applied to the structures of natural products to yield better candidates with enhanced pharmacological properties. This strategy has successfully generated many natural product derivatives as approved drugs.6–9

Brusatol is a natural product of quassinoids with a skeleton of C-20.10–12 Ever since the structure was determined in 1968, its activities against Plasmodium, cancer, HIV, malaria, neoplasms, and hypoglycemia have been reported.13 The interest in this natural compound as a promising candidate against chemo-resistance of cancers has increased since a novel mechanism of its inhibition of the Nrf2 pathway was discovered.14,15 However, in vitro and in vivo evaluations of its characteristics as a drug candidate have revealed several issues that fall short of expectations. A relatively short half-life in plasma was observed, and pharmacokinetic studies in both mice and rats showed that the levels of this compound decreased very rapidly from plasma.16,17

The toxicity of brusatol in previous studies has also severely limited its potential development as a therapeutic agent. In an acute toxicity study in mice, the lethal dose (LD50) of brusatol was found to be 31.3 μmol/kg (×520 μg/μmol = 16.2 mg/kg) when a single dose was administered orally.18 When brusatol was given orally at 3 mg/kg/day (QD) to mice infected with Plasmodium berghei for four consecutive days, four out of five of the mice died.19 However, brusatol was effective when given at 2 mg/kg intraperitoneally (IP) to IDH1-mutated subcutaneous xenograft nude mice every other day, for a total of five times for IDH1-mutated malignancies. Therefore, it appeared that the structure of brusatol needed to be optimized in order to improve the toxicity and ADME profiles for potential clinical applications.20

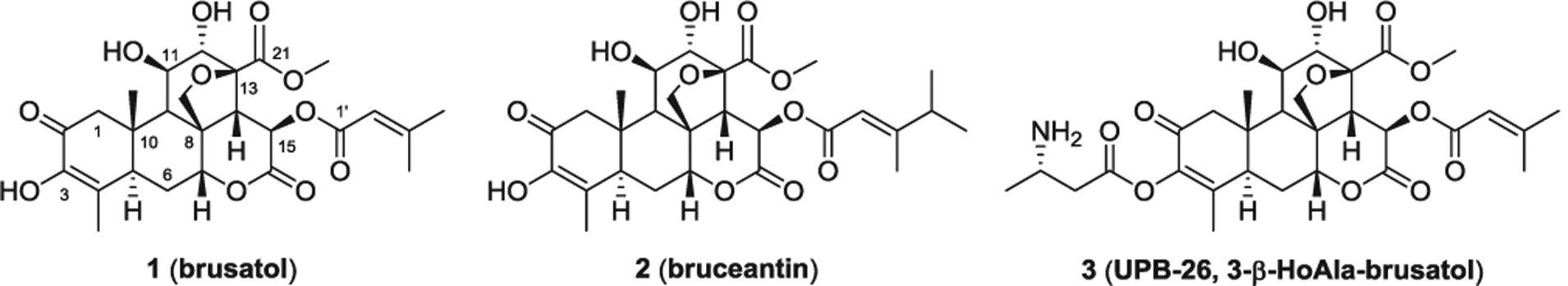

Recently, in generating modified brusatol analogs, we discovered that brusatol and its new amino acid conjugate 3 (UPB-26, Fig. 1) can be efficiently used against hematologic malignancies by targeting the PI3Kγ isoform.21,22 Herein, we will present the rationale for the design, synthesis and evaluation of these related analogs with improved ADME profiles.

Fig. 1.

Structures of brusatol, bruceantin, and UPB-26, 3-(3-β-HoAla)-brusatol.

The reason why brusatol causes toxicity has not been understood. Furthering complications, four metabolites of brusatol were detected from the plasma of rats after intravenous administration in a pharmacokinetic (PK) study, and the pharmacological effects of these metabolites are also not known.17 To better explore its stability and metabolism, we conducted metabolite identification (MetID) studies of brusatol in both human and mouse liver microsomes. The result was that four metabolites, including two dehydrogenation products and two oxidation products, were formed. The remaining brusatol at 60 min was 64% and 40% respectively in human and mouse liver microsomes based on the area percentages of all derived fractions (Fig. 2). The moderate stability of brusatol in liver microsomes suggests a liability and that the improvement of the stability in liver should help to narrow down the potential factors leading to the toxicity.

Fig. 2.

MetID study of brusatol in human and mouse liver microsomes. The results showed four metabolites were formed and brusatol was recovered at moderate yields at 60 min.

Brusatol contains a lactone ring and two esters at C-21 and C-1′, and three hydroxyls at C-3, C-11, and C-12, respectively. Due to being located at different structural positions and chemical environments, the congeners, i.e. similar functional groups, possess different reactivities. Among the two ester groups, the C-1′ ester can be selectively hydro-lyzed by using KOH in methanol;23 and the C-21 methyl ester can be converted into an acid with LiI in pyridine,24 although a direct aqueous hydrolysis was also reported to afford the demethylated product.10 In comparing the three hydroxyls, the enolic hydroxyl at C-3 is the most susceptible to esterification and alkylation.22–25

Previous structure–activity studies against leukemia demonstrated that the C-3 acylated derivatives of brusatol can be as active as or more active than brusatol, and that the free hydroxyl groups at C-11 and C-12, as well as the C-2 enone double bond in ring A, are necessary for antileukemic activity.24,26 Additionally, the senecioyl group at C-15 can be replaced with other acyl groups, including fluorinated acyl groups.25,26 Similar SAR trends were also observed for bruceantin, a close analog of brusatol, in studies investigating its inhibition of protein synthesis (2, Fig. 1).27,28 It is worth noting from anti-malarial studies that several C-3 acyl derivatives could, not only just maintain the activities, but also potentially reduce the toxicities.29,30 The toxicity of brusatol was also alleviated by diacyl derivatives at C-3 and C-12 and ester hydrolysis at C-21, but the improved properties of these derivatives were attributed to the NO-releasing capability from their pendant furoxan moiety.18

Amino acids and peptides have previously been used as pro-moieties in prodrug conjugate formation.31–33 This approach has led to results such as the successful augmentation of aqueous solubility due to the introduction of an ammonium salt,34 an increase of oral bioavailability via active human peptide transporter mediated absorption,32,35 the amelioration of the toxicity or side effects by changing the distribution36 or masking the functional groups temporarily during the drug delivery,37 improvement of target delivery,38 and mitigation of undesired metabolism.39 We envisioned that this strategy could be applied to brusatol through the introduction of amino acids or peptides as acyl groups at C-3 of brusatol. The resulting ester conjugates were expected to improve the stability and reduce the toxicity relative to the parent compound brusatol. A small number of amino acids were already reported to have been used at C-3 of brusatol, but that was together with other variations at either at C-15 or C-21 in anti-malarial research, in which weaker activities were observed.29–30 Without knowing which amino acid could be beneficial, we screened a diverse set of promoieties including lipophilic Boc protected amino acids, unprotected amino acids, and di- and tri-peptides first.

Synthesis of amino acid or peptide conjugates through the 3-enol

As exemplified in Scheme 1, the conjugates (4) with α-amino acids, or β-amino acids, can be obtained through the esterification of brusatol with Boc-protected amino acids mediated by EDCI and DMAP. The Boc-protecting group can then be removed under acidic condition to provide conjugates with free amine groups (5).21 Conjugates with dipep-tides and tripeptides can also be prepared by a similar procedure.

Scheme 1.

General route for synthesis of 3-amino acid conjugates 4 with amines protected and 5 with free amines.

The brusatol conjugates inhibit viability of hematologic malignancy derived cells

To investigate their inhibitory activities on the growth of EBV-associated lymphomas and other types of lymphomas, we first evaluated the conjugates, 4 and 5, for their effects on the viability of Raji cells, a Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) cell line, when treated at 100 nM for 72 h. UPB-14, UPB-15, UPB-26, and UPB-31, which we have previously reported21, are included for comparison. As illustrated in Fig 3, for Boc protected amino acid conjugates, smaller amino acid esters, such as glycine UPB-15, alanine 6, and proline 11, gave moderate inhibition, while larger amino acid esters did not show significant inhibition. In contrast, all of the unprotected amino acid conjugates demonstrated improved inhibitions over their corresponding more lipophilic Boc-protected precursors (Fig 3C). Similarly, conjugates with smaller amino acids exhibited better potencies than those with larger amino acids. In addition to the β-homoalanine conjugate UPB-26 and proline conjugate UPB-31, the di-glycine peptide conjugate 20, di-homoalanine peptide conjugate 21, and tri-glycine peptide conjugate 23 also displayed potent activities comparable to or higher than the parent brusatol. Interestingly, di-alanine peptide conjugate 22 was not active. Next, we examined the activities of these four conjugates against cell lines derived from other types of human hematologic malignancies. The cell lines included: MOLT-4, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells; SU-DHL-6 and SU-DHL-10, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cells; RPMI-8226, multiple myeloma (MM) cells; and LCL1, an EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell line. These cell lines represent the cell models of a range of hematologic malignancies. The results demonstrated that the active conjugates selected from Raji cell line all had broad and potent inhibitory effects on the majority of these cell lines, including EBV-associated lymphomas (LCL1). But in particular, MOLT-4 and SU-DHL-10 cells showed more sensitivity to these analogs, except 22, compared to the others (Fig 3D).

Fig. 3.

Identification of active brusatol conjugates. A, B, Structures of conjugates; C, activities on Raji cell lines; D, activities of selected compounds on five other cell lines.

The superior activities of the compounds with homoalanine (UPB-26) and proline moieties (UPB-31) compared to other amino acids used for conjugation prompted us to investigate the structure-activity relationship around these two amino acids. Therefore, structurally close analogs including D-β-homoalanine and D-proline, derivatives of UPB-26 like acetyl and methylsulfonyl, and UPB-31 were prepared and evaluated for their activities on the Raji cell line (Fig. 4). The results showed that compounds 25 and 27, with opposite amino acid configurations, and 28 and 34, with an acetyl on the β-homoalanine and a geminal difluoro substitution on the proline respectively, possessed similar activities. But 29, with a methylsulfonyl group, and 30–33, with side chains more hydrophobic than the methyl in the β-homoalanine, lost activities (Fig 4C). The active analogs also presented potencies in the five other cell lines comparable to that of the parent brusatol (Fig 4B).

Fig. 4.

SAR studies around UPB-26 and UPB-31.

The non-stereoselective feature of β-homoalanine and proline in terms of chirality when conjugated to brusatol (UPB-26 vs. 25 and UPB-31 vs. 27) triggered our interest over whether the activities of these conjugates were from brusatol instead of from the conjugates, and if the function of these amino acids or peptides was just being a delivery tool before being cleaved off by esterases. To address this possibility, we synthesized analogs of UPB-15 and 20, compounds 39–48, which have polar or hydrophobic terminals connected via a covalent ether bond to brusatol, as opposed to an ester (Scheme 2). Due to the non-cleavable nature of these ether bonds under regular conditions, these compounds were not expected to release brusatol by interactions with esterase. In vitro tests revealed that the majority of these analogs were not active, indicating that introduction of these hydrophobic groups, polar amide, and acids had a detrimental effect on the activity of the brusatol pharmacophore. However, a diglycine peptide analog, 40, which bears a free amine group like in UPB-26 and is a close analog of diglycine conjugate 20, demonstrated moderate activity on the Raji cell line (Fig 5A) and moderate to good activities on other extended cell lines (Fig 5B) as well, suggesting that a conjugate itself may have some activity, albeit not as potent as the parent brusatol.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 40, 3- derivatives with a covalent bond, through alkylation.

Fig. 5.

Non-cleavable analogs derived from 3-hydroxyl.

Stability is an important factor to consider for prodrug conjugates. With several brusatol conjugates which have comparable potencies in hand, we selected UPB-15 and UPB-26 from two different families in order to evaluate and to compare to brusatol using in vitro assays that are related to intravenous (IV) and oral (PO) drug administrations (Table 1). Compound UPB-15 has relatively low stability in simulated gastric fluid (SGF) and simulated intestinal fluid (SIF), and thus is not a good candidate for PO administration. Compound UPB-26 has a good solubility in water despite being slightly less soluble than brusatol. Brusatol is stable in both human and rat plasmas. However, a decrease in the amount of UPB-26 and the generation of brusatol were observed. At 60 min, 44% of UPB-26 remained and 47% of UPB-26 was converted into brusatol (Table 1) in human plasma; while only 39% was left and 60% of conversion to brusatol was recorded in rat plasma. These results demonstrated that UPB-26 can be transformed into brusatol in both human and rat plasmas at moderate rates. When these two compounds were tested in both SGF and SIF, high stabilities were observed for brusatol. Compound UPB-26 also displayed good percentage of recovery, with 97% and 76% respectively after 4 hrs of incubation.

Table 1.

Solubility and stability evaluation of UPB-26 compared to brusatol.

| Compound | Solubility in water (μg/mL) | Plasma stability remaining % at 60 min | Stability in simulated gastric fluid, Remaining % at 4 hr | Stability in simulated intestinal fluid, Remaining % at 4 hr | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Rat | ||||

| Brusatol | 902 | 91 | 100 | 109 | 100 |

| 26TFA | 738 | 44 (47)* | 39 (60)* | 97 | 76 |

| 15 | NA | NA | NA | 25 | 42 |

percentage of brusatol converted from UPB-26.

In order to determine if UPB-26 induces liver microsomal metabolism changes, we investigated the MetID profile of UPB-26 in mouse liver microsomes under the same conditions as for brusatol. As illustrated in Fig. 6, a different pattern of metabolism was observed for UPB-26, as compared to that of brusatol (Fig. 2). However, 87% of UPB-26 (area%) was detected after 60 min of incubation while five identified metabolites were all in relatively small percentages. In comparison to the performance of the parent compound brusatol (40%, Fig. 2), UPB-26 has significantly improved metabolic stability in the mouse liver.

Fig. 6.

MetID study of UPB-26 showed that UPB-26 was the major fraction after 60 min of incubation in mouse microsomes.

To assess the toxicity profile of these conjugates of brusatol, we examined the toxicity of UPB-15 and UPB-26 in comparison to brusatol. Six-week-old male NOD.CB17PrkdcSCID/J (NOD/SCID) mice (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME, USA; 4 mice per group) were intraperitoneally injected with a dose of 5 mg/kg of one of three compounds - brusatol, UPB-15, or UPB-26 - every other day, three times per week. The mice were monitored and euthanized after 24 days of treatment. The survival curve, shown in Fig 7, appears that UPB-26 is less toxic than brusatol. At 5 mg/kg, all four mice survived in the group treated with UPB-26, compared to the three from the group with brusatol treatment and two with UPB-15 treatment. Previously, we evaluated the toxicities of UPB-15, UPB-26, and brusatol at 10 mg/kg.21 From these two studies it is apparent that there is a dose dependence of brusatol on the toxic effect, with 75% of survival at 5 mg/kg but 25% at 10 mg/kg. Compound UPB-15 appears to be even more toxic with 50% of survival at 5 mg/Kg and 0% at 10 mg/kg. However, conjugate UPB-26 did not show any obvious signs of toxicity even after more than three weeks of treatment at both doses. These results indicate that conjugate UPB-26 exhibits much less toxicity than brusatol. Because brusatol is released from conjugate prodrug UPB-26, the improved toxicity is likely attributed to the improved stability in liver microsomes and moderate rate of conversion to brusatol in plasma. More detailed work will be done in the following studies.

Fig. 7.

Toxicity evaluation of UPB-15, UPB-26 compared to brusatol in mice under 5 mg/kg dose. NS, not significant.

In conclusion, to reduce the toxicity of brusatol and maintain its efficacy, we have prepared conjugates with five types of moieties, including those connected with ester bonds- lipophilic Boc protected amino acids, amino acids, dipeptides, and tripeptides, and non-cleavable conjugates through ether bonds. These new compounds were then evaluated in the Raji cell line. A number of conjugates with smaller amino acid and peptides demonstrated activities comparable to brusatol. These active compounds were further tested in five other types of human hematologic malignancies derived cell lines with high expression of PI3Kγ isoform and demonstrated broad inhibitory activities. UPB-26, a conjugate of brusatol with a L-β-homoalanine, has good chemical stabilities at physiological PHs (SGF and SIF), and can be converted to brusatol in both human and rat plasmas at moderate rates. When incubated with mouse liver microsomes in a MetID study, UPB-26 displayed a different metabolism pattern from brusatol and exhibited a higher stability (87% vs 40% at 60 min). Finally, UPB-26 showed much better improved safety compared to brusatol in mice upon IP administration. No lethality was observed at a dose of 5 mg/kg while brusatol had 25% of death rate. Combining our previous mouse toxicity study result, in which UPB-26 and brusatol had 100% and 25% survival rates respectively at a dose of 10 mg/kg, we demonstrated that UPB-26 can be used safely at up to 10 mg/kg while brusatol needs to be used at lower than 5 mg/kg when dosed every other day in mice. Further evaluation of the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and efficacy at a higher dose of UPB-26 will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health public health service Grants P30-CA016520, R01-CA171979, P01-CA174439, and R01-CA177423 to ESR, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania through the Baruch S. Blumberg Institute to YD, and the Abramson Comprehensive Cancer Center Director fund. We also thank professor Zhi Wei of the Department of Computer Science, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, New Jersey for the advice on the data evaluation.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127553.

References

- 1.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs from 1981 to 2014. J Nat Prod. 2016;79:629–661. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bharate SS, Mignani S, Vishwakarma RA. Why are the majority of active compounds in the cns domain natural products? A critical analysis? J Med Chem. 2018;61(23):10345–10374. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang MM, Qiao Y, Ang EL, Zhao H. Using natural products for drug discovery: the impact of the genomics era. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2017;12(5):475–487. 10.1080/17460441.2017.1303478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharifi-Rad J, Ozleyen A, Boyunegmez Tumer T, et al. Natural products and synthetic analogs as a source of antitumor drugs. Biomolecules. 2019;9(11):679 10.3390/biom9110679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tewari D, Rawat P, Singh PK. Adverse drug reactions of anticancer drugs derived from natural sources. Food Chem Toxicol. 2019;123:522–535. 10.1016/j.fct.2018.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao Z, Morris-Natschke SL, Lee KH. Strategies for the Optimization of Natural Leads to Anticancer Drugs or Drug Candidates. Med Res Rev 2016;36(1):32–91. 10.1002/med.21377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang S, Dong G, Sheng C. Structural simplification of natural products. Chem Rev. 2019;119(6):4180–4220. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ynigez-Gutierrez AE, Bachmann BO. Fixing the unfixable: the art of optimizing natural products for human medicine. J Med Chem. 2019;62(18):8412–8428. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding Y, Ding C, Ye N, et al. Discovery and development of natural product oridonininspired anticancer agents. Eur J Med Chem. 2016;122:102–117. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sim KY, Sims JJ, Geissman TA. Constituents of brucea samatrana roxb. I Brusatol J Org Chem. 1968;33:429–431. 10.1021/jo01265a093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chakraborty D, Pal A. Quassinoids: Chemistry and Novel Detection Techniques In: Ramawat K, Mérillon JM, eds. Natural Products. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg; 2013:3345–3366. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curcino Vieira IJ, Braz-Filho R. Quassinoids: Structural Diversity, Biological Activity and Synthetic Studies. In: Atta-ur-Rahman, ed. Studies in Natural Product Chemistry, Vol 33 Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers. 2005:433–492. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aarthi R Brusatol- as potent chemotherapeutic regimen and its role on reversing EMT transition. J Pharm Sci & Res. 2019;11(5):1753–1762. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ren D, Villeneuve NF, Jiang T, et al. Brusatol enhances the efficacy of chemotherapy by inhibiting the Nrf2-mediated defense mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(4):1433–1438. 10.1073/pnas.1014275108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai SJ, Liu Y, Han S, Yang C. Brusatol, an NRF2 inhibitor for future cancer therapeutic. CellBiosci. 2019;9:45 10.1186/s13578-019-0309-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo N, Zhang X, Bua F, et al. Determination of brusatol in plasma and tissues by LC–MS method and its application to a pharmacokinetic and distribution study in mice. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2017;1053:20–26. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo N, Xu X, Yuan G, Chen X, Wen Q, Guo R. Pharmacokinetic, metabolic profiling and elimination of brusatol in rats. Biomed Chromatogr. 2018;32:e4358 10.1002/bmc.4358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang W, Xie J, Xu S, et al. Novel nitric oxide-releasing derivatives of brusatol as anti-inflammatory agents: design, synthesis, biological evaluation, and nitric oxide release studies. J Med Chem. 2014;57(18):7600–7612. 10.1021/jm5007534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Neill MJ, Bray DH, Boardman P, et al. Plants as sources of antimalarial drugs, Part 4: Activity of Brucea javanica fruits against chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in vitro and against Plasmodium berghei in vivo. J Nat Prod. 1987;50(1):41–48. 10.1021/np50049a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Lu Y, Celiku O, et al. Targeting IDH1-mutated malignancies with NRF2 blockade. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(10):1033–1041. 10.1093/jnci/djy230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pei Y, Hwang N, Lang F, et al. Quassinoid analogs with enhanced efficacy in treatment of hematologic malignancies specifically target the PI3Kγ isoform. Commun Biol. 2020;3:267 10.1038/s42003-020-0996-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crocker KE, Pei Y, Robertson ES, Winkler JD. Synthesis of a novel bruceantin analog via intramolecular etherification. Can J Chem. 2020;98(6):270–272. 10.1139/cjc-2019-0437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okano M, Lee KH. Antitumor Agents. 43. Conversion of Bruceoside-A into Bruceantin. J. Org. Chem 1981;46:1138–1141. 10.1021/jo00319a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hitotsuyanagi Y, Kim IH, Hasuda T, Yamauchi Y, Takeya K. A structure–activity relationship study of brusatol, an antitumor quassinoids. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:4262–4271. 10.1016/j.tet.2006.01.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohno N, Fukamiya N, Okano M, Tagahara K, Lee KH. Synthesis of cytotoxic fluorinated quassinoids. Bioorg Med Chem. 1997;5(8):1489–1495. 10.1016/S0968-0896(97)00095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee KH, Okano M, Hall IH, Brent DA, Soltmann B. Antitumor agents XLV: Bisbrusatolyl and brusatolyl esters and related compounds as novel potent antileukemic agents. J Pharm Sci. 1982;71(3):338–345. 10.1002/jps.2600710320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao LL, Kupchan SM, Horwitz SB. Mode of action of the antitumor compound bruceantin, an inhibitor of protein synthesis. Mol Pharmacol. 1976;12(1):167–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukamiya N, Lee KH, Muhammad I, et al. Structure-activity relationships of quassinoids for eukaryotic protein synthesis. CancerLett. 2005;220(1):37–48. 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen D, Wright CW, Phillipson JD, Toth I, Kirby GC, Warhurst DC. In vitro anti-malarial and cytotoxic activities of semisynthetic derivatives of brusatol. Eur J Med Chem. 1993;28(3):265–269. 10.1016/0223-5234(93)90143-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murakami N, Umezome T, Mahmud T, et al. Anti-malarial activities of acylated bruceolide derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;8(5):459–462. 10.1016/S0960-894X(98)00045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vale N, Ferreira A, Matos J, Fresco P, Gouveia MJ. Amino Acids in the Development of Prodrugs. Molecules. 2018;23:2318 10.3390/molecules23092318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rautio J, Kumpulainen H, Heimbach T, et al. Prodrugs: design and clinical applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:255–270. 10.1038/nrd2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rautio J, Meanwell NA, Di L, Hageman MJ. The expanding role of prodrugs in contemporary drug design and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:559–587. 10.1038/nrd.2018.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lv K, Li W, Wu S, et al. Amino acid prodrugs of NVR3–778: Design, synthesis and anti-HBV activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2020;30(9):127103 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Vrueh RL, Smith PL, Lee CP. Transport of L-valine-acyclovir via the oligopeptide transporter in the human intestinal cell line, Caco-2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:1166–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krylov IS, Kashemirov BA, Hilfinger JM, McKenna CE. Evolution of an amino acid based prodrug approach: stay tuned. Mol Pharm. 2013;10:445–458. 10.1021/mp300663j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma J, Wu S, Zhang X, et al. Ester prodrugs of IHVR-19029 with enhanced oral exposure and prevention of gastrointestinal glucosidase interaction. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2017;8:157–162. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sofia MJ, Bao D, Chang W, et al. Discovery of a beta-d-2ʹ-deoxy-2ʹ-alpha-fluoro-2ʹ-beta-C-methyluridine nucleotide prodrug (PSI-7977) for the treatment of hepatitis C virus. J Med Chem. 2010;53:7202–7218. 10.1021/jm100863x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pelletier JC, Chen S, Bian H, et al. Dipeptide prodrugs of the glutamate modulator riluzole. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2018;9:752–756. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]