Abstract

Background

Phelan–McDermid syndrome (PMS) or 22q13 deletion syndrome is a rare developmental disorder characterized by hypotonia, developmental delay (DD), intellectual disability (ID), autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and dysmorphic features. Most cases are caused by 22q13 deletions encompassing many genes including SHANK3. Phenotype comparisons between patients with SHANK3 mutations (or deletions only disrupt SHANK3) and 22q13 deletions encompassing more than SHANK3 gene are lacking.

Methods

A total of 29 Mainland China patients were clinically and genetically evaluated. Data were obtained from medical record review and a standardized medical history questionnaire, and dysmorphology evaluation was conducted via photographic evaluation. We analyzed 22q13 deletions and SHANK3 small mutations and performed genotype–phenotype analysis to determine whether neurological features and other important clinical features are responsible for haploinsufficiency of SHANK3.

Results

Nineteen patients with 22q13.3 deletions ranging in size from 34 kb to 8.7 Mb, one patient with terminal deletions and duplications, and nine patients with SHANK3 mutations were included. All mutations would cause loss-of function effect and six novel heterozygous variants, c.3838_3839insGG, c.3088delC, c.3526G > T, c.3372dupC, c.3120delC and c.3942delC, were firstly reported. Besides, we demonstrated speech delay (100%), DD/ID (88%), ASD (80%), hypotonia (83%) and hyperactivity (83%) were prominent clinical features. Finally, 100% of cases with monogenic SHANK3 deletion had hypotonia and there was no significant difference between loss of SHANK3 alone and deletions encompassing more than SHANK3 gene in the prevalence of hypotonia, DD/ID, ASD, increased pain tolerance, gait abnormalities, impulsiveness, repetitive behaviors, regression and nonstop crying which were high in loss of SHANK3 alone group.

Conclusions

This is the first work describing a cohort of Mainland China patients broaden the clinical and molecular spectrum of PMS. Our findings support the effect of 22q13 deletions and SHANK3 point mutations on language impairment and several clinical manifestations, such as DD/ID. We also demonstrated SHANK3 haploinsufficiency was a major contributor to the neurological phenotypes of PMS and also responsible for other important phenotypes such as hypotonia, increased pain tolerance, impulsiveness, repetitive behaviors, regression and nonstop crying.

Keywords: Phelan–McDermid syndrome (PMS), Mainland China, SHANK3 haploinsufficiency, Genotype–phenotype correlation

Introduction

Phelan–McDermid syndrome (PMS, OMIM 606232), also called 22q13 deletion syndrome is a rare developmental disorder with diverse clinical features [1–4]. Given the heterogeneity of genetic etiology, patients diagnosed as PMS usually comorbid with multi disorders, such as neural system related disorders (severely delayed speech, DD/ID, ASD, and seizures, et al.), recurring upper respiratory tract infections, gastroesophageal reflux, and minor dysmorphic features (dysplastic ears, bulbous nose, and long eyelashes, et al.) [5, 6].

PMS is caused by deletions ranging from hundreds of kilobases (kb) to over nine megabases (Mb) in size in the 22q13 region [7]. Chromosomal abnormalities include simple terminal deletions, interstitial deletions, translocations and ring chromosomes. Almost all individuals identified to date involve SHANK3, mapping to the distal end of 22q13.33 [1, 8–11]. SHANK3 encodes a scaffolding protein enriched in the postsynaptic density of glutamatergic synapses and play a critical role in synaptic function and dendrite formation [12, 13]. Deletions or point mutations in SHANK3 have been identified in patients ascertained for ASD at a rate of about 2% [14], intellectual disability (ID) at a rate of about 2% [15], and schizophrenia at a rate of 0.6–2.16% [16, 17].

Currently, the hypothesis is that SHANK3 haploinsufficiency is responsible for major neurological features of PMS [8, 18, 19]. Wilson and colleagues detected few correlations between the deletion size and the most neurological features. They have also reported correlations between deletion size and other important phenotypes including hypotonia, head circumference, recurrent ear infections, pointed chin, and dental anomalies [19]. In addition, genotype–phenotype correlation analyses suggest that the size of deletion is a predictor of phenotypic severity. Specifically, developmental delay [19–21], hypotonia [19–21], dysmorphic features [5, 21, 22], language status [22, 23], social communication deficits related to ASD [5, 22], renal abnormalities [5, 22], lymphedema [5, 22], seizures [5] show a higher incidence or increased severity with larger deletions. However, genotype–phenotype correlation analyses have largely focused on patients with 22q13 deletions, only two reports on PMS have contained a few patients carrying SHANK3 mutations or deletions only disrupt SHANK3 [5, 22]. Silvia De Rubeis and colleagues compared clinical features in individuals with SHANK3 mutations to 22q13 deletions including SHANK3 from the literature. However, they did not analyze genotype–phenotype correlations. The lack of genotype–phenotype correlations between patients with SHANK3 mutations (or deletions only disrupt SHANK3) and patients with deletions encompassing more than SHANK3 gene have hindered the exploration of SHANK3 deficiency in the important phenotypes in PMS.

Over the past few years, more than 1400 cases were identified worldwide. However, thus far, only four 22q13 deletions and a SHANK3 mutation in patients with ID have been reported in Mainland China [24]. Here, we report 29 previously undescribed Mainland Chinese patients with PMS. Our main goal was to explore the contribution of SHANK3 haploinsufficiency to the important phenotypes besides neurological features. We also presented clinical profile and genetic spectrum of the patients, aiming at expanding the molecular and phenotypic spectrum of PMS.

Results

Characterization of 22q13.3 deletions and SHANK3 mutations in PMS patients

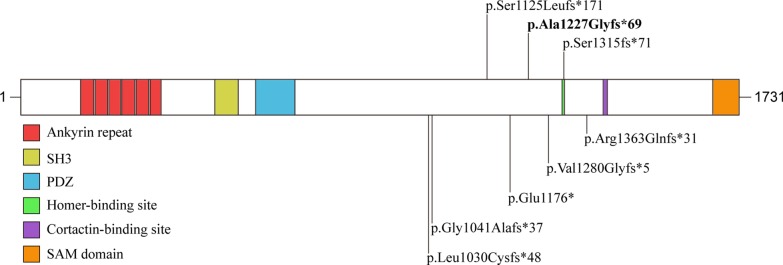

We reported 29 children identified by a custom 22q13 microarray or Whole exome sequencing (WES). Nineteen children carried 22q13 terminal deletions and one child harbored terminal deletions accompanied by proximal duplications (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The deletions ranged from 34 kb to 8.7 Mb with a mean size of 3617 kb. Three children had small deletions ranging from 34 to 57 kb in size that only contain SHANK3 gene. Nine children with SHANK3 mutations tested through WES were also observed (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The variants were named following Human Genome Variation Society nomenclature guideline. As reported previously [25], the human genome reference assembly (GRCh37/hg19) misses the beginning of exon 11, nucleotide and amino acid positions were corrected according to the SHANK3 mRNA (NM_033517.1) and protein (NP_277052.1) in RefSeq. The variants included eight frameshift and one nonsense mutations (Table 2, Fig. 2). Remarkably, we found a recurrent frameshift mutation, c.3679dupG (p. Ala1227Glyfs*69) in two unrelated patients. The mutations arose de novo in nine patients. Six variants caused loss of the Homer-binding, the Cortactin-binding and the Sterile Alpha Motif (SAM) domains. One variant disrupted Homer-binding domains and caused loss of the Cortactin-binding and SAM domains. And one variant caused loss of the Cortactin-binding and the SAM domains (Fig. 2). Besides, we assessed pathogenicity of SHANK3 mutations in our cohort. Variants listed in Table 2 met the following criteria: (1) loss-of-function variants (frameshift and nonsense, splice site), (2) De novo (both maternity and paternity confirmed) in a patient with the disease and no family history, and (3) absent from control databases (EVS and gnomAD). Except for one variant (c.3942delC, p.Gly1041Alafs*37) was likely pathogenic, the rest variants were pathogenic according to the ACMG variant interpretation guidelines [26]. Six novel heterozygous variants, c.3838_3839insGG, c.3088delC, c.3526G > T, c.3372dupC, c.3120delC and c.3942delC, were reported.

Table1.

Details of the 22q13.3 deletions in 20 individuals with PMS

| Patient | Ascertainment method | Rearrangement | Array coordinates (hg19) | Deletion or duplication size (kb) | Genes | Inheritance | Other chromosome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | SNP | Deletion | 2,243,352,384–51,197,766 | 7987 | Many | NK | None |

| P2 | SNP | Deletion | 43,428,841–51,197,766 | 7956 | Many | De novo | None |

| P3 | aCGH | Deletion | 45,193,180–51,178,213 | 6042 | Many | De novo | None |

| P4 | SNP | Duplication and | (43,199,808–47,056,500) × 3; | 3891 | Many | NK | None |

| Deletion | 47,056,555–51,197,766 | 4044 | Many | ||||

| P5 | SNP | Deletion | 43,629,482–51,197,766 | 7568 | Many | NK | None |

| P6 | aCGH | Deletion | 46,615,777–51,178,213 | 4710 | Many | NK | None |

| P8 | SNP | Deletion | 46,688,687–51,220,738 | 4426 | Many | NK | None |

| P9 | SNP | Deletion | 51,073,379–51,197,838 | 124 | Many | NK | None |

| P15 | SNP | Deletion | 51,121,363–51,197,766 | 76 | SHANK3, ACR | De novo | None |

| P16 | SNP | Deletion | 43,674,432–51,139,778 | 7649 | Many | NK | None |

| P17 | SNP | Deletion | 47,486,331–51,183,840 | 3698 | Many | NK | None |

| P18 | SNP | Deletion | 48,100,752–51,177,162 | 3004 | Many | NK | None |

| P19 | QPCR | Deletion | 51,121,768–51,121,840; 51,158,612–51,160,865 | 57 | SHANK3 | De novo | None |

| P20 | SNP | Deletion | 51,128,324–51,197,766 | 69 | SHANK3, ACR | NK | None |

| P21 | SNP | Deletion | 49,882,209–51,197,726 | 1316 | Many | NK | None |

| P23 | SNP | Deletion | 50,990,475–51,115,526 | 125 | Many | NK | None |

| P25 | WES | Deletion | 42,522,566–51,216,419 | 8909 | Many | NK | None |

| P26 | MLPA | Deletion | 51,123,013–51,169,790 | 46 | SHANK3 | NK | None |

| P27 | SNP | Deletion | 51,135,991–51,169,740 | 34 | SHANK3 | NK | None |

| P29 | SNP | Deletion | 50,155,448–51,197,766 | 1042 | Many | NK | None |

NK not known, WES whole exome sequencing, aCGH array-CGH, SNP single nucleotide polymorphism, MLPA multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, QPCR quantitative real-time PCR

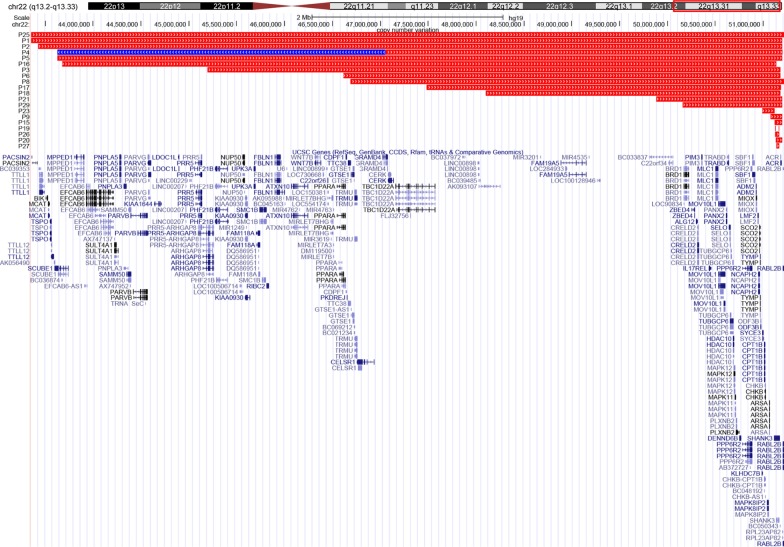

Fig. 1.

Distribution of deletions and duplications among 20 China mainland patients that varied from 34 kb to 8.7 Mb

Table 2.

Summarization of SHANK3 gene variants in 9 patients with PMS

| Patient | Variant locationa | Variant type | Protein change | Inheritance | Literature report | MutationTaster | ACMG classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P7 | c.3120delC | Frameshift | p. Gly1041Alafs*37(Het) | NK | – | Disease causing | Likely pathogenic |

| P10 | c.3372dupC | Frameshift | p. Ser1125Leufs*171(Het) | De novo | – | Disease causing | Pathogenic |

| P11 | c.3526G > T | Nonsense | p. Glu1176*(Het) | De novo | – | Disease causing | Pathogenic |

| P12 | c.4086_4087delAC | Frameshift | P. Arg1363Glnfs*31(Het) | NK | Nature. 2017;542(7642):433–438 | Disease causing | Pathogenic |

| P13 | c.3679dupG | Frameshift | p. Ala1227Glyfs*69(Het) | De novo | Nat Genet. 2007;39(1):25‐27 | Disease causing | Pathogenic |

| P14 | c.3679dupG | Frameshift | p. Ala1227Glyfs*69(Het) | NK | Nat Genet. 2007;39(1):25‐27 | Disease causing | Pathogenic |

| P22 | c.3088delC | Frameshift | p. Leu1030Cysfs*48(Het) | De novo | – | Disease causing | Pathogenic |

| P24 | c.3942delC | Frameshift | p. Ser1315fs*71(Het) | De novo | – | Disease causing | Pathogenic |

| P28 | c.3838_3839insGG | Frameshift | p. V1280Gfs*5(Het) | De novo | – | Disease causing | Pathogenic |

NK not known, * the stop codon, ACMG American College of Medical Genetics and Genomic

Fig. 2.

Distribution of SHANK3 mutations in our cases. Recurrent mutations are indicated in bold. Protein domains are from UniProt; the homer and cortactin binding sites are indicated as previously reported [2]

Overall prevalence of clinical phenotype

The most common phenotype seen in our cases (Tables 3, 4 and Additional file 1: Table S1) were speech delay (100%), DD/ID (88%), ASD (80%), hypotonia (83%), distinctive behavioral abnormalities such as hyperactivity (83%), impulsiveness (76%) and repetitive behaviors (69%), developmental/neurological abnormalities such as increased pain tolerance (62%) and gait abnormalities (55%). Other common features included any type of seizures (24%), chewing difficulties (31%), biting self or others (30%), hair pulling (31%), aggressive behavior (30%), nonstop crying (45%), sleep disturbance (24%), diarrhea/constipation (23%) and eczema (28%), and minor dysmorphic traits included descending palpebral fissure (33%), ear anomalies (24%), periorbital fullness (24%), strabismus (29%) and frontal bossing (19%).

Table 3.

Developmental and behavioral features of patients with PMS in our cohort as compared to the literature

| Feature | N | Total | % | Literature frequencya (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental/neurological | ||||

| Speech (age ≥ 3) | ||||

| Absent speech | 11 | 20 | 55 | |

| Sentences | 9 | 20 | 45 | |

| Walk independently (age ≥ 3) | 20 | 20 | 100 | |

| DD/ID | 23 | 26 | 88 | |

| Any type of seizures (including febrile seizures) | 7 | 29 | 24 | 14–41 |

| Overheats or turns red easily | 5 | 29 | 17 | 68b |

| Decreased perspiration | 2 | 29 | 7 | 60b |

| Overly sensitive to touch | 5 | 29 | 17 | 46b |

| Increased pain tolerance | 18 | 29 | 62 | 29–100 |

| Arachnoid cyst | 4 | 29 | 14 | 19b |

| Hypotonia | 24 | 29 | 83 | 29–100 |

| Gait abnormalities | 16 | 29 | 55 | 93c |

| Behavioral features | ||||

| Autism spectrum disorder (age ≥ 3) | 16 | 20 | 80 | 31b |

| Impulsiveness | 22 | 29 | 76 | 47c |

| Chewing difficulties (difficulty with eating) | 9 | 29 | 31 | 58c |

| Biting (self or others) | 9 | 29 | 30 | 46b |

| Hair pulling | 9 | 29 | 31 | 41b |

| Excessive screaming | 5 | 29 | 17 | 31b |

| Aggressive behavior | 9 | 29 | 30 | 28b |

| Nonstop crying (crying non-stop for 3 h) | 13 | 29 | 45 | 21b |

| Hyperactivity | 24 | 29 | 83 | 47c |

| Self-injury | 3 | 29 | 10 | |

| Pica | 3 | 29 | 10 | |

| Repetitive behaviors | 20 | 29 | 69 | 100c |

| Sleep disturbance | 7 | 29 | 24 | 41–46 |

| Regression | 13 | 29 | 45 | 65d |

| Other clinical features | ||||

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 2 | 29 | 7 | > 25–44 |

| Diarrhea/constipation | 7 | 29 | 23 | 38–41 |

| Congenital heart defect | 4 | 29 | 14 | 3c |

| Genital anomalies | 1 | 23 | 4 | 5b |

| Eczema | 8 | 29 | 28 | 18d |

| Enzyme deficiency | 0 | 29 | 0 | 4b |

| Immune deficiency | 1 | 29 | 3 | 12b |

| Recurring upper respiratory tract infections | 6 | 29 | 21 | 29–100 |

| Hearing loss | 1 | 29 | 3 | 3d |

| Allergies | 5 | 29 | 17 | |

| Asthma | 1 | 29 | 3 | |

| Renal abnormalities | 3 | 21 | 14 | 17–38 |

| Lymphedema | 0 | 29 | 0 | 22–29 |

| Hypothyroid | 0 | 29 | 0 | 6b |

| Diabetes | 0 | 29 | 0 | 2b |

| Vitiligo | 0 | 29 | 0 | 3c |

aFrequencies based on the literature review available [27]

bFrequencies available in the clinical and genomic evaluation of 201 patients with PMS [23]

cFrequencies based on a Brazilian cohort of individuals with PMS [22]

dFrequency based on the analysis of PMS individuals carrying SHANK3 point mutations [28]

eFrequencies based on a previous report [5]

Table 4.

Dysmorphic features in patients with Phelan–McDermid syndrome

| Dysmorphic features | N | Total | % | Literature frequencya (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microcephalyc | 2 | 20 | 10 | 13 |

| Macrocephalyd | 1 | 20 | 5 | 7 |

| Sparse eyebrows | 3 | 21 | 14 | 18b |

| Long eyelashes | 1 | 21 | 5 | 45 |

| Periorbital fullness | 5 | 21 | 24 | 45 |

| Descending palpebral fissure | 7 | 21 | 33 | |

| Hypertelorism | 3 | 21 | 14 | 36 |

| Strabismus | 6 | 21 | 29 | 26 |

| Epicanthal folds | 1 | 21 | 5 | 57 |

| Wide nasal bridge | 3 | 21 | 14 | 16 |

| Large/wide nose | 2 | 21 | 10 | |

| Bulbous nose | 3 | 21 | 14 | 80 |

| Anteverted nares | 1 | 21 | 5 | 9b |

| Full cheeks | 1 | 21 | 5 | 25 |

| High forehead | 4 | 21 | 19 | |

| Short philtrum | 1 | 21 | 5 | 0b |

| Ear anomalies | 5 | 21 | 24 | 54 |

| Thick lower vermillion | 3 | 21 | 14 | 27b |

| Down-turned mouth | 3 | 21 | 14 | |

| Short stature/delayed growthe | 1 | 29 | 3 | 11 |

| Tall stature/accelerated growthf | 5 | 29 | 17 | 9 |

Development, language skills and neurological features

DD/ID was evaluated by analyzing the patients’ medical records or questionnaire (n = 26). Four patients were severe to extremely severe and nine patients were mild to moderate. Eleven cases were diagnosed as DD/ID but we were not able to assess the degree of intellectual disability, and two showed normal intelligence (Tables 3, 4 and Additional file 1: Table S1).

All individuals (21/20, 100%) could walk independently (Table 3 and Additional file 1: Table S1) by 3 years of age, although fine and gross motor delays could be observed in all individuals at the age of test. The mean age when individuals acquired this skill was 20 months, ranging from 12 to 33 months of age. Only three patients (P1, P5 and P9) had ever been received rehabilitation therapy by 3 years of age. The majority of individuals showed hypotonia (24/29, 83%) and gait abnormalities (16/29, 55%).

Language delay was notable (20/20, 100%) over the age of 3 years (Results are summarized in Table 3). In total, 52% of the cases (11/21) had no speech, 9 had “sentences” (spoke single word or spoke in phrases or sentences). The degree of language delay in ten patients ranged from mild to moderate and seven patients ranged from severe to extremely severe.

Seven participants (7/29, 43%) demonstrated seizures (Table 2). Abnormal electroencephalography (EEG) were described in six participants (6/18, 33%), including three without clinical seizures. MRI showed abnormal findings in fourteen participants (13/21, 62%), including delayed myelination (n = 2), abnormal corpus callosum (n = 5), enlargement of ventricles (n = 2), white matter abnormalities (n = 1), generous extracerebral spaces (n = 1) and large cisterna magna (n = 2).

Behavioral features

By the age of 3 years, 80% patients (16/20) was diagnosed as ASD. As listed in Table 3, the majority of patients were reported as hyperactivity (24/29, 83%), impulsiveness (22/29, 76%) and repetitive behaviors (20/29, 69%) such as hand flapping, teeth grinding. Patients were also prone to nonstop crying (13/29, 45%) and regression (13/29, 45%) affecting language, cognitive and motor ability.

Other clinical features

According to parents’ report, the majority of participants had increased pain tolerance (18/29, 62%). In addition, chewing difficulties (9/29, 31%), eczema (8/29, 28%) diarrhea/constipation (7/29, 23%), renal problems (3/21, 14%) and recurring upper respiratory tract infections (6/29, 21%) are common. Similarly, hearing loss reported in 3% of cases with PMS, were uncommon [27]. Lymphedema, hypothyroid, diabetes, vitiligo and enzyme deficiency have been reported in patients with PMS [5, 22, 23, 27], but were absent in individuals in our cases (Table 3).

Dysmorphic features

Dysmorphology examinations were performed in 21 patients by two clinicians. They all had at least one feature (Table 4 and Additional file 1: Table S2). Dysmorphic features in our cohort were not as so common as reported in previous studies [5, 22, 23]. The most frequent features in this study were ear anomalies (5/21, 24%), descending palpebral fissure (7/21, 33%), periorbital fullness (5/21, 24%), strabismus (6/21, 29%), frontal bossing (4/21, 19%).

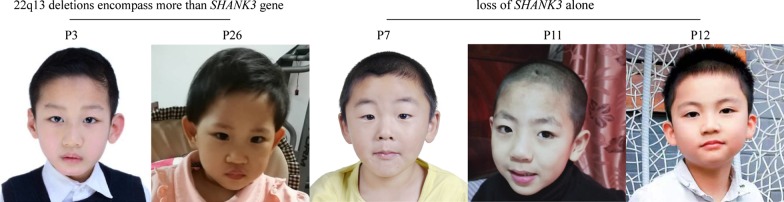

SHANK3 mutations (or deletions only disrupt SHANK3) effects

To investigate the role of SHANK3 haploinsufficiency in the important phenotypes, we divided patients into two groups. Group 1 (n = 17) included individuals with deletions that encompass more than SHANK3 gene. Group 2 (n = 12) consists of individuals with SHANK3 mutations or deletions that only encompass SHANK3. As shown in Table 5, the frequency of the hypotonia in patients in the group 2 was higher compared to that in the group 1 (100% vs. 71%), with statistical significance near the borderline (Fisher’s exact two-sided test P = 0.059), suggesting the haploinsufficiency for SHANK3 may contribute to the hypotonia. There was no significant difference between group 1 and group 2 in the frequency of other clinical features including DD/ID (10/11, 91%), ASD (7/8, 88%), increased pain tolerance (7/12, 58%), gait abnormalities (6/12, 50%), impulsiveness (11/12, 92%), repetitive behaviors (9/12, 75%), regression (7/11, 63%), nonstop crying (7/12, 58%) and minor dysmorphic traits including ear anomalies (4/10, 40%) and descending palpebral fissure (3/10, 30%) which are high in loss of SHANK3 alone group (Table 5). In addition, as shown in Fig. 3, children in group 1 did not show more severe dysmorphic traits compared to children in group 2. The minor dysmorphic traits the patients in Fig. 3 had were listed as followings: Patient 3 had short philtrum and down-turned mouth, patient 25 had long eyelashes and down-turned mouth, patient 7 had a descending palpebral fissure, strabismus and wide nasal bridge, patient 11 had a bulbous nose and fleshy ears and patient 12 had low set ears.

Table 5.

Comparison of the prevalence of phenotypes between patients with 22q13 deletions encompassing more than SHANK3 gene and loss of SHANK3 alone

| Clinical feature | 22q13 deletions encompass more than SHANK3 gene | Loss of SHANK3 alone | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical features | |||

| Microcephalyb | 2/11(18%) | 1/10(10%) | 1.000 |

| Macrocephalyc | 0/11(0%) | 1/10(10%) | 1.000 |

| Sparse eyebrows | 1/11(9%) | 2/10(20%) | 0.586 |

| Long eyelashes | 0/11(0%) | 1/10(10%) | 1.000 |

| Periorbital fullness | 3/11(27%) | 2/10(20%) | 1.000 |

| Descending palpebral fissure | 4/11(36%) | 3/10(30%) | 1.000 |

| Hypertelorism | 3/11(27%) | 0/10(0%) | 0.214 |

| Strabismus | 4/11(36%) | 2/10(20%) | 0.635 |

| Epicanthal folds | 0/11(0%) | 1/10(10%) | 1.000 |

| Wide nasal bridge | 2/11(18%) | 1/10(10%) | 1.000 |

| Large/wide nose | 2/11(18%) | 0/10(0%) | 1.000 |

| Bulbous nose | 1/11(9%) | 2/10(20%) | 1.000 |

| Anteverted nares | 0/11(0%) | 1/10(10%) | 1.000 |

| Full cheeks | 0/11(0%) | 1/10(10%) | 1.000 |

| Frontal bossing | 2/11(18%) | 2/10(20%) | 1.000 |

| Short philtrum | 1/11(9%) | 0/10(0%) | 1.000 |

| Ear anomalies | 1/11(9%) | 4/10(40%) | 0.149 |

| Thick lower lip | 1/11(9%) | 2/10(20%) | 0.586 |

| Down-turned mouth | 2/11(18%) | 1/10(10%) | 1.000 |

| Short stature/delayed growthd | 1/17(6%) | 1/12(8%) | 1.000 |

| Tall stature/accelerated growthe | 4/17(24%) | 1/12(8%) | 0.370 |

| Developmental/neurological | |||

| DD/ID | 13/15(87%) | 10/11(91%) | 1.000 |

| Speech (absent speech versus sentences, age ≥ 3) | 8/12(67%) | 3/8(38%) | 0.370 |

| Any type of seizures (including febrile seizures) | 4/17(24%) | 3/12(25%) | 1.000 |

| Overheats or turns red easily | 3/17(13%) | 2/12(17%) | 1.000 |

| Decreased perspiration | 2/17(6%) | 0/12(0%) | 1.000 |

| Overly sensitive to touch | 3/17(18%) | 2/12(17%) | 1.000 |

| Increased pain tolerance | 11/17(65%) | 7/12(58%) | 1.000 |

| Arachnoid cyst | 3/17(18%) | 1/12(8%) | 0.622 |

| Hypotonia | 12/17(71%) | 12/12(100%) | 0.059 |

| Gait abnormalities | 10/17(59%) | 6/12(50%) | 1.000 |

| Neuroimaging abnormalities | 9/12(75%) | 4/9(44%) | 0.159 |

| Behavioral features | |||

| Autism spectrum disorder (age ≥ 3) | 10/17(59%) | 7/8(88%) | 0.205 |

| Impulsiveness | 11/17(65%) | 11/12(92%) | 0.187 |

| Chewing difficulties (difficulty with eating) | 5/17(29%) | 5/12(42%) | 0.694 |

| Biting (self or others) | 5/17(29%) | 4/12(33%) | 1.000 |

| Hair pulling | 4/17(19%) | 5/12(42%) | 0.231 |

| Excessive screaming | 3/17(24%) | 2/12(17%) | 1.000 |

| Aggressive behavior | 5/17(29%) | 4/12(33%) | 1.000 |

| Nonstop crying (crying non-stop for 3 h) | 6/17(35%) | 7/12(58%) | 0.274 |

| Hyperactivity | 14/17(82%) | 10/12(83%) | 1.000 |

| Self-injury | 3/17(24%) | 0/12(0%) | 0.246 |

| Pica | 1/17(6%) | 2/12(17%) | 0.553 |

| Repetitive behaviors | 11/17(65%) | 9/12(75%) | 0.694 |

| Sleep disturbance | 4/17(19%) | 3/12(25%) | 1.000 |

| Regression | 5/17(29%) | 7/11(63%) | 0.121 |

| Other clinical features | |||

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 2/17(12%) | 0/12(0%) | 0.498 |

| Diarrhea/constipation | 3/17(24%) | 4/12(33%) | 1.000 |

| Genital anomalies | 1/15(7%) | 0/7(0%) | 1.000 |

| Eczema | 4/17(24%) | 4/12(33%) | 0.683 |

| Immune deficiency | 1/17(7%) | 0/12(0%) | 1.000 |

| Recurring upper respiratory tract infections | 5/17(29%) | 1/12(8%) | 0.354 |

| Hearing loss | 1/17(7%) | 0/12(0%) | 1.000 |

| Congenital heart defect | 2/17(12%) | 1/12(8%) | 1.000 |

| Allergies | 3/17(24%) | 2/12(17%) | 1.000 |

| Asthma | 1/17(7%) | 0/12(0%) | 1.000 |

aAll P values are Fisher’s Exact

bHead circumference < 3rd percentile

cHead circumference > 98th percentile

dHeight < 3rd percentile

eHeight > 98th percentile

Fig. 3.

Representative images of patients with PMS showing mild dysmorphism. There was no significant difference between patients with 22q13 deletions encompassing more than SHANK3 gene and patients with loss of SHANK3 alone in dysmorphic features

Discussion

Up to now, only four cases with 22q13 deletions or a SHANK3 mutation were reported in a cohort of patients with ID in Mainland China [24]. To fill in the gap, we presented the 29 participants with PMS in Mainland China to broaden the clinical and genetic spectrum of PMS especially in Chinese ethic group.

Findings in our cases indicate SHANK3 mutations are fully penetrant in accordance with previous estimates [28]. Notably, seven out of eight variants lead to the loss of Homer-binding, the Cortactin-binding, and the SAM domains of the protein, which are critical for SHANK3 interactions with other PSD proteins. Homer-binding domain of SHANK3 binds to the group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors, such as mGluR1/5 [29]. Functional studies have found impairments in hippocampal synaptic transmission and plasticity in an exon 21 deletion (coding for the Homer binding domain) mouse model [30]. SAM domain of SHANK3 has been shown be crucial for postsynaptic localization [31]. Two patients (P13 and P15) carry a c.3679dupG which would generate a premature stop codon at position 1227, causing the loss of the Homer-binding, the Cortactin-binding and the SAM domains of the protein. Functional studies on c.3679dupG have been shown to affect neuronal development and decreased growth cone motility [32].

The key symptoms of PMS are speech delay, DD/ID, ASD and hypotonia, which is in accordance with previous studies [32]. We found a high frequency of hyperactivity (83%) and impulsiveness (76%), which have been previously reported in the literature. 100% of children were able to walk but at a delayed age, which is compatible with a different PMS cohort [32]. Lymphedema, hypothyroid, diabetes, vitiligo and enzyme deficiency absent in individuals in our cases have been reported in patients with PMS [5, 22, 23, 27]. Furthermore, there was a remarkable difference in the frequency of certain PMS features (i.e. overheats or turns red easily, gait abnormalities, gastroesophageal reflux, long eyelashes, epicanthal folds and so on) between our cohort and reported cohorts in literatures. These discrepancies could be related to the relatively young age of the individuals in your cohort (mean age = 4.46 years). Aside from that, the fact that no patients have been evaluated in person which represents a major limitation as well as the fact that only a small percentage of the patients have received the same amount of laboratory and imaging tests contributed to the discrepancies.

Comparisons of phenotypes between patients with loss of SHANK3 alone and that with deletions encompassing more than SHANK3 gene showed that there was no significant difference between two groups in the clinical features including DD/ID, absence of speech and ASD in accordance with a previous study [19]. We also demonstrated hypotonia frequency was slightly higher in the loss of SHANK3 alone group. However, hypotonia frequency showed a correlation with the larger deletions in their study. The smallest deletion in their study encompassed SHANK3, RABL2B and ACR genes which cannot implicate the role of SHANK3 alone in hypotonia. In addition, we observed a high frequency of the increased pain tolerance, gait abnormalities, repetitive behaviors, regression, and minor dysmorphic traits including ear anomalies and descending palpebral fissure in loss of SHANK3 alone group which are in line with previous estimates in individuals with PMS due to SHANK3 point mutations [28]. There was no significant difference between two groups in these features. These results indicate that SHANK3 haploinsufficiency affects these important phenotypes. Although their work compared clinical features in individuals with SHANK3 mutations to 22q13 deletions including SHANK3 from the literature, they did not analyze genotype–phenotype correlations between two groups. In the present study, Fisher’s exact two-sided test was used to assess statistical significance in important phenotypes between two groups to analyze genotype–phenotype correlations for the first time. Furthermore, 17 patients with SHANK3 point mutations and 60 individuals with 22q13 deletions from the literature in their study were not the same cohort. Thus, the methods de Rubeis et al. collected data were different from that in the literature leading to information bias. Finally, cases with 22q13 deletions de Rubeis et al. used to compare phenotypes included two patients (SH29 and SH32) who carried SHANK3 point mutations (c.2497delG and c.1527G > A respectively), so the prevalence of phenotypes in patients with 22q13 deletions were not correct. Several studies have examined genotype–phenotype associations in SHANK3 deficiency and results are inconsistent. Phenotypes correlated with deletion size in their studies included renal abnormalities, lymphedema, large or fleshy hands, dolichocephaly, facial asymmetry, feeding problems, genital anomalies, head circumference, recurrent ear infections, pointed chin, and dental anomalies. However, only two reports on PMS have consisted of a few patients carrying SHANK3 mutations or deletions only disrupt SHANK3 [5, 22]. In addition, these medical comorbidities frequency were all low or absent in two groups in our study probably leading to the insignificance because of the small sample size. Latha et al. found deletion size was statistical significance associated with ASD. Our evaluation of ASD depended on medical record review while their study included evaluations using standard diagnostic scales with ASD (e.g., ADOS-2 and ADI-R).

There were several limitations to this analysis. We obtained medical history by medical record review or questionnaires completed by parents and the collected data may be subject to recall or information bias. Besides, assessments using standard diagnostic scales with ASD and developmental delay were not available, and thus analyses depend on medical record review. The phenotype comparisons identified in our analysis are heavily influenced by sample size, future studies could be done in larger samples to provide a clear role of SHANK3 haploinsufficiency in the important phenotypes in PMS.

In summary, this is the first detailed report of the comparisons of phenotypes between PMS patients with deletions encompassing many genes including SHANK3 and loss of SHANK3 alone. Our findings show loss of SHANK3 alone is sufficient to produce the characteristic phenotypes of PMS, including developmental/neurological abnormalities, behavioral features, gastrointestinal problems and dysmorphic features. We also observed a high frequency of the speech delay, DD/ID, ASD, hypotonia, increased pain tolerance, impulsiveness, repetitive behaviors, regression, nonstop crying, and minor dysmorphic traits including ear anomalies and descending palpebral fissure in loss of SHANK3 alone group and there was no significant difference between two groups regarding these important features. These findings extend the role of SHANK3 haploinsufficiency in PMS beyond its well-known role at the neurological features.

Methods

Cohort

Twenty nine previously unreported patients with clinical and genetic diagnosis of PMS in Mainland China from the China League of PMS Rare Disease were recruited in this study from 2018 to 2020. This cohort included 20 males (66%) and 10 females (34%), with age ranging from 1.9 to 9 years old (mean = 4.46, SD = 2.18). Parents or guardians provided genetic exams, medical record review and completed a standardized medical history questionnaire. The questionnaire included queries about the individuals’ stature, head circumference, developmental/neurological features, behavioral abnormalities, and additional clinical features. Level of developmental delay, autism diagnosis, MRI information, perinatal events, growth parameters at birth were abstracted from medical record review. In addition to that, 22 families also provided pictures of frontal, bilateral view of the face, and a view with the eyes closed of their affected children. Two clinicians from Xinhua Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University assessed the pictures of the patients to analyze their morphological features. All the clinical features refer to it at the age of test, except level of developmental delay, autism diagnosis, MRI information, renal abnormities, perinatal events, growth parameters at birth which were abstracted from medical record review.

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Xinhua Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (XHEC-D-2020-072) and parents provided informed consent forms.

Genetic testing

Twenty patients have a deletion at 22q13.3 encompassing SHANK3. Different exams and platforms were applied: array-CGH (n = 2), SNP array (n = 15) or WES (n = 3) were performed in 20 individuals. Three deletions only disrupt SHANK3 were validated by MLPA or QPCR (see details in Table 1). SHANK3 mutations were identified by whole exome sequencing (WES) and then validated by Sanger sequencing in nine individuals. Nine genetic tests were conducted by our research team and the others by outsourced laboratories.

Statistical analysis

Children were divided into two groups to investigate the role of SHANK3 haploinsufficiency in the important phenotypes. Group 1 (n = 17) included individuals with deletions encompass more than SHANK3 gene. Group 2 (n = 12) consists of individuals with SHANK3 mutations or deletions only encompassing SHANK3. Fisher’s exact two-sided test was used to assess statistical significance in important phenotypes between two groups. Results were judged to be statistically significant at P < 0.05 and of borderline significance at 0.05 < P < 0.10.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Main clinical features of individuals with PMS and dysmorphic features in Mainland China PMS patients.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the affected individuals and their families for the participation in the study.

Abbreviations

- SHANK3

SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 3

- PMS

Phelan–McDermid syndrome

- OMIM

Online Mendelian inheritance in man

- DD

Developmental disability

- ID

Intellectual disability

- ASD

Autism spectrum disorder

- SD

Standard deviation

- Array-CGH

Microarray-based comparative genome hybridization

- SNP-array

Single nucleotide polymorphism array

- WES

Whole exome sequencing

- MLPA

Multiplex ligation probe amplification

- QPCR

Real-time quantitative PCR detecting system

- Kb

Kilobase

- Mb

Megabase

- EVS

Exome variant server

- gnomAD

Genome aggregation database

- ACMG

American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics

- EEG

Electroencephalography

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- mGluRs

Metabotropic glutamate receptors

- ADOS-2

Autism diagnostic observation schedule, second edition

- ADI-R

Autism diagnostic interview-revised

Authors’ contributions

NX, HL, TY, FL and YY: conception and design of the study; NX, FL and YY: drafting the manuscript or figures; YS, review and editing the manuscript; JX and BX: evaluation of the pictures of individuals for the morphological analysis; LW, YF, LX and YZ: acquisition and analysis of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2018YFC1002204 and No. 2019YFC1005100, to YGY); Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (No. 20204Y0453, to NX); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81670812 and No. 81873671, to YGY); the Jiaotong University Cross Biomedical Engineering (No. YG2017MS72, to YGY); the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (No. 201740192, to YGY); the Shanghai Shen Kang Hospital Development Center new frontier technology joint project (No. SHDC12017109, to YGY); the Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (No. 19140904500, to YGY); Shanghai Municipal Education Commission-Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant Support (No. 20191908, to YGY); Foundation of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (No. shslczdzk05702, to YGY).

Availability of data and materials

All data are shown in this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted with the approval of Ethics Committee of Xinhua Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (XHEC-D-2020-072) and parents provided written informed consent before participants were enrolled.

Consent for publication

All participants/families agree for the publication of the presented work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Na Xu, Hui Lv and Tingting Yang contribute equally to this work

Contributor Information

Fei Li, Email: feili@shsmu.edu.cn.

Yongguo Yu, Email: yuyongguo@shsmu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13023-020-01592-5.

References

- 1.Ponson L, Gomot M, Blanc R, Barthelemy C, Roux S, Munnich A, et al. 22q13 deletion syndrome: communication disorder or autism? Evidence from a specific clinical and neurophysiological phenotype. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):146. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0212-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durand CM, Betancur C, Boeckers TM, Bockmann J, Chaste P, Fauchereau F, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 are associated with autism spectrum disorders. Nat Genet. 2007;39(1):25–27. doi: 10.1038/ng1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prasad C, Prasad AN, Chodirker BN, Lee C, Dawson AK, Jocelyn LJ, et al. Genetic evaluation of pervasive developmental disorders: the terminal 22q13 deletion syndrome may represent a recognizable phenotype. Clin Genet. 2000;57(2):103–109. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2000.570203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Precht KS, Lese CM, Spiro RP, Huttenlocher PR, Johnston KM, Baker JC, et al. Two 22q telomere deletions serendipitously detected by FISH. J Med Genet. 1998;35(11):939–942. doi: 10.1136/jmg.35.11.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soorya L, Kolevzon A, Zweifach J, Lim T, Dobry Y, Schwartz L, et al. Prospective investigation of autism and genotype–phenotype correlations in 22q13 deletion syndrome and SHANK3 deficiency. Mol Autism. 2013;4(1):18. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phelan MC, Rogers RC, Saul RA, Stapleton GA, Sweet K, McDermid H, et al. 22q13 deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2001;101(2):91–99. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20010615)101:2<91::aid-ajmg1340>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonaglia MC, Giorda R, Beri S, De Agostini C, Novara F, Fichera M, et al. Molecular mechanisms generating and stabilizing terminal 22q13 deletions in 44 subjects with Phelan/McDermid syndrome. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(7):e1002173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delahaye A, Toutain A, Aboura A, Dupont C, Tabet AC, Benzacken B, et al. Chromosome 22q13.3 deletion syndrome with a de novo interstitial 22q13.3 cryptic deletion disrupting SHANK3. Eur J Med Genet. 2009;52(5):328–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhar SU, del Gaudio D, German JR, Peters SU, Ou Z, Bader PI, et al. 22q13.3 deletion syndrome: clinical and molecular analysis using array CGH. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2010;152a(3):573–581. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Misceo D, Rødningen OK, Barøy T, Sorte H, Mellembakken JR, Strømme P, et al. A translocation between Xq21.33 and 22q13.33 causes an intragenic SHANK3 deletion in a woman with Phelan–McDermid syndrome and hypergonadotropic hypogonadism. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2011;155a(2):403–408. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nesslinger NJ, Gorski JL, Kurczynski TW, Shapira SK, Siegel-Bartelt J, Dumanski JP, et al. Clinical, cytogenetic, and molecular characterization of seven patients with deletions of chromosome 22q13.3. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;54(3):464–472. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monteiro P, Feng G. SHANK proteins: roles at the synapse and in autism spectrum disorder. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18(3):147–157. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yi F, Danko T, Botelho SC, Patzke C, Pak C, Wernig M, et al. Autism-associated SHANK3 haploinsufficiency causes Ih channelopathy in human neurons. Science (New York, NY) 2016;352(6286):aaf2669. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boccuto L, Lauri M, Sarasua SM, Skinner CD, Buccella D, Dwivedi A, et al. Prevalence of SHANK3 variants in patients with different subtypes of autism spectrum disorders. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(3):310–316. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leblond CS, Nava C, Polge A, Gauthier J, Huguet G, Lumbroso S, et al. Meta-analysis of SHANK mutations in autism spectrum disorders: a gradient of severity in cognitive impairments. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(9):e1004580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Sena CA, Degenhardt F, Strohmaier J, Lang M, Weiss B, Roeth R, et al. Investigation of SHANK3 in schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet Part B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2017;174(4):390–398. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gauthier J, Champagne N, Lafrenière RG, Xiong L, Spiegelman D, Brustein E, et al. De novo mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 in patients ascertained for schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(17):7863–7868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906232107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonaglia MC, Giorda R, Borgatti R, Felisari G, Gagliardi C, Selicorni A, et al. Disruption of the ProSAP2 gene in a t(12;22)(q24.1;q13.3) is associated with the 22q13.3 deletion syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69(2):261–268. doi: 10.1086/321293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson HL, Wong AC, Shaw SR, Tse WY, Stapleton GA, Phelan MC, et al. Molecular characterisation of the 22q13 deletion syndrome supports the role of haploinsufficiency of SHANK3/PROSAP2 in the major neurological symptoms. J Med Genet. 2003;40(8):575–584. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.8.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luciani JJ, de Mas P, Depetris D, Mignon-Ravix C, Bottani A, Prieur M, et al. Telomeric 22q13 deletions resulting from rings, simple deletions, and translocations: cytogenetic, molecular, and clinical analyses of 32 new observations. J Med Genet. 2003;40(9):690–696. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.9.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarasua SM, Dwivedi A, Boccuto L, Rollins JD, Chen CF, Rogers RC, et al. Association between deletion size and important phenotypes expands the genomic region of interest in Phelan–McDermid syndrome (22q13 deletion syndrome) J Med Genet. 2011;48(11):761–766. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samogy-Costa CI, Varella-Branco E, Monfardini F, Ferraz H, Fock RA, Barbosa RHA, et al. A Brazilian cohort of individuals with Phelan–McDermid syndrome: genotype–phenotype correlation and identification of an atypical case. J Neurodev Disord. 2019;11(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s11689-019-9273-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarasua SM, Boccuto L, Sharp JL, Dwivedi A, Chen CF, Rollins JD, et al. Clinical and genomic evaluation of 201 patients with Phelan–McDermid syndrome. Hum Genet. 2014;133(7):847–859. doi: 10.1007/s00439-014-1423-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gong X, Jiang YW, Zhang X, An Y, Zhang J, Wu Y, et al. High proportion of 22q13 deletions and SHANK3 mutations in Chinese patients with intellectual disability. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e34739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolevzon A, Cai G, Soorya L, Takahashi N, Grodberg D, Kajiwara Y, et al. Analysis of a purported SHANK3 mutation in a boy with autism: clinical impact of rare variant research in neurodevelopmental disabilities. Brain Res. 2011;1380:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolevzon A, Angarita B, Bush L, Wang AT, Frank Y, Yang A, et al. Phelan–McDermid syndrome: a review of the literature and practice parameters for medical assessment and monitoring. J Neurodev Disord. 2014;6(1):39. doi: 10.1186/1866-1955-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Rubeis S, Siper PM, Durkin A, Weissman J, Muratet F, Halpern D, et al. Delineation of the genetic and clinical spectrum of Phelan–McDermid syndrome caused by SHANK3 point mutations. Mol Autism. 2018;9:31. doi: 10.1186/s13229-018-0205-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tu JC, Xiao B, Naisbitt S, Yuan JP, Petralia RS, Brakeman P, et al. Coupling of mGluR/Homer and PSD-95 complexes by the Shank family of postsynaptic density proteins. Neuron. 1999;23(3):583–592. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80810-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kouser M, Speed HE, Dewey CM, Reimers JM, Widman AJ, Gupta N, et al. Loss of predominant Shank3 isoforms results in hippocampus-dependent impairments in behavior and synaptic transmission. J Neurosci. 2013;33(47):18448–18468. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3017-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boeckers TM, Liedtke T, Spilker C, Dresbach T, Bockmann J, Kreutz MR, et al. C-terminal synaptic targeting elements for postsynaptic density proteins ProSAP1/Shank2 and ProSAP2/Shank3. J Neurochem. 2005;92(3):519–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durand CM, Perroy J, Loll F, Perrais D, Fagni L, Bourgeron T, et al. SHANK3 mutations identified in autism lead to modification of dendritic spine morphology via an actin-dependent mechanism. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(1):71–84. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Main clinical features of individuals with PMS and dysmorphic features in Mainland China PMS patients.

Data Availability Statement

All data are shown in this article.