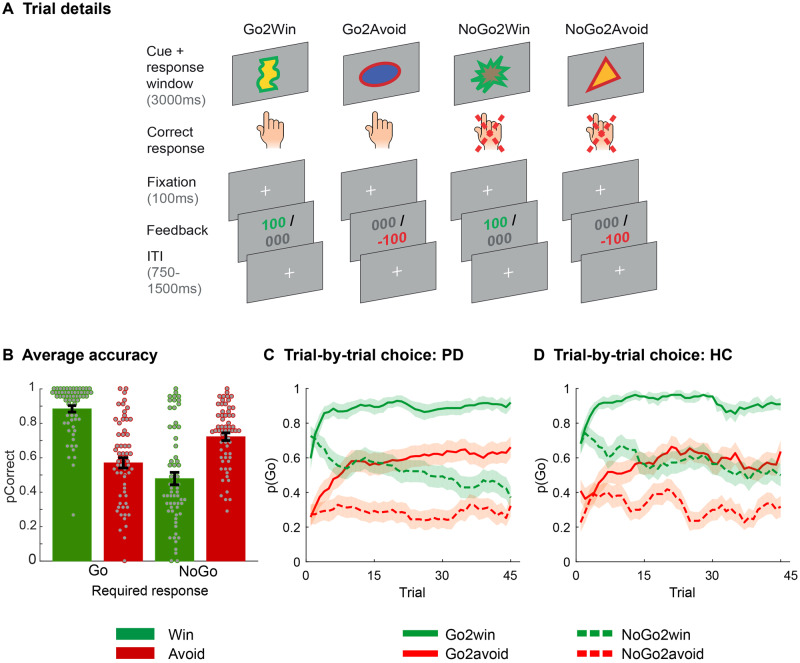

Figure 1.

Motivational Go/NoGo learning task and performance. (A) Each trial starts with either a Win or an Avoid cue; signalled by the green or red edge of the cue. For each cue, the participant needs to learn the correct response, either press the spacebar (Go) or not (NoGo). Participants have to respond while the cue is on the screen. Outcomes are presented 100 ms after cue offset. In total, four cues are presented, reflecting the 2 × 2 factorial design of response requirement (Go/NoGo) and cue valence (Win/Avoid), such that for each valence there is one cue where Go is correct, and one cue where NoGo is correct. Feedback is probabilistic: correct responses are followed by reward (Win cues) or a neutral outcome (Avoid cues) in 80% of the time, and by a neutral outcome (Win cues) or punishment (Avoid cues) otherwise. For incorrect responses, these probabilities are reversed. (B) Average accuracy per cue type—performance of the cues congruent with the automatic motivational bias (Go2Win, NoGo2Avoid)—is higher than for the incongruent trials (NoGo2Win, Go2Avoid). (C and D) Trial-by-trial proportion of Go responses [± standard error of the mean (SEM)], displayed using a within-subject five-trial average sliding window, for both Parkinson’s disease patients (C) and healthy controls (D). From the first trial onwards, a clear motivational bias is apparent as participants start by making more Go responses for Win cues, and more NoGo responses for Avoid cues. However, during the course of the experiment both participant groups learn to adjust responses towards the correct contingencies. HC = healthy controls; PD = Parkinson’s disease.