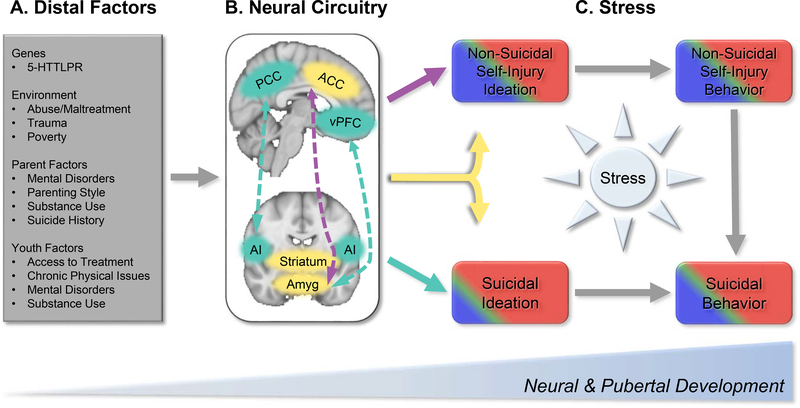

Figure 2.

The neurodevelopmental model of STB and NSSI highlights distal and proximal processes that may potentiate risk for self-injurious behaviors during a critical period of development. There are a wide range of (A) distal risk factors that shape neuromaturation, including genetic, environment, parental, and youth factors. These distal factors occur in the context of ongoing pubertal and neuromaturation from childhood to young adulthood. This review highlights a number of brain regions and connectivity patterns (B) that show alterations potentially unique to suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STB; Teal) and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI; Purple), or common across both (Yellow). In STB, these include connections between the default mode network (hub in the posterior cingulate cortex [PCC]) and salience network (hub in the anterior insula [AI]) as well as between the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) and the amygdala (amyg). NSSI shows alterations in connections between the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and amygdala. Both STB and NSSI implicate structural and functional alterations in the striatum, amygdala, and ACC. (C) Coupled with acute stressors—particularly interpersonal stress—these distal neural markers may increase risk for engaging in suicidal and non-suicidal behaviors. Acute stress may directly impact brain development, and concurrently, may disrupt top-down cortical processes related to self-referential processing rumination, and future-oriented thinking, which may lead to suicidal and non-suicidal thinking. Stressors that become chronic in nature may tax limbic systems, which modulate arousal and approach behaviors. Disruptions to bottom-up and top-down connections may, for some, facilitate the transition from thinking to acting. More broadly, stress also elicits a range of negative emotions (e.g., sadness, anger), and in the absence of effective emotion regulation strategies, this may then lead to STB and/or NSSI. Presently, there is not sufficient evidence attributing sex differences in STB and NSSI to discrete neural circuitry. Epidemiological research, however, shows that NSSI thoughts and behaviors are more common in female (red) versus male (blue) adolescents, though estimates vary (e.g., (6, 7)). Similarly, suicidal thinking (15% vs. 9%) and behaviors (6% vs. 2%) are more common in females versus males (e.g., (4)). Although not often examined in large epidemiological cohorts, NSSI and STB is proportionally higher among transgender and gender-non-conforming youth (green) (140, 141). Accounting for stress exposure using interview and ambulatory approaches may shed key insights into shared and unique neural markers that lead to suicidal versus non-suicidal behaviors.