Abstract

Introduction

Healthcare workers are vulnerable to adverse mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. We assessed prevalence of mental disorders and associated factors during the first wave of the pandemic among healthcare professionals in Spain.

Methods

All workers in 18 healthcare institutions (6 AACC) in Spain were invited to web-based surveys assessing individual characteristics, COVID-19 infection status and exposure, and mental health status (May 5 – September 7, 2020). We report: probable current mental disorders (Major Depressive Disorder-MDD- [PHQ-8≥10], Generalized Anxiety Disorder-GAD- [GAD-7≥10], Panic attacks, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder –PTSD- [PCL-5≥7]; and Substance Use Disorder –SUD-[CAGE-AID≥2]. Severe disability assessed by the Sheehan Disability Scale was used to identify probable “disabling” current mental disorders.

Results

9,138 healthcare workers participated. Prevalence of screen-positive disorder: 28.1% MDD; 22.5% GAD, 24.0% Panic; 22.2% PTSD; and 6.2% SUD. Overall 45.7% presented any current and 14.5% any disabling current mental disorder. Workers with pre-pandemic lifetime mental disorders had almost twice the prevalence than those without. Adjusting for all other variables, odds of any disabling mental disorder were: prior lifetime disorders (TUS: OR=5.74; 95%CI 2.53-13.03; Mood: OR=3.23; 95%CI:2.27-4.60; Anxiety: OR=3.03; 95%CI:2.53-3.62); age category 18-29 years (OR=1.36; 95%CI:1.02-1.82), caring “all of the time” for COVID-19 patients (OR=5.19; 95%CI: 3.61-7.46), female gender (OR=1.58; 95%CI: 1.27-1.96) and having being in quarantine or isolated (OR= 1.60; 95CI:1.31-1.95).

Conclusions

One in seven Spanish healthcare workers screened positive for a disabling mental disorder during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Workers reporting pre-pandemic lifetime mental disorders, those frequently exposed to COVID-19 patients, infected or quarantined/isolated, female workers, and auxiliary nurses should be considered groups in need of mental health monitoring and support.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Healthcare Workers, Mental Disorders, Need for Care, Disability, Adverse Mental Health

Abstract

Introducción

Los profesionales sanitarios son vulnerables al impacto negativo en salud mental de la pandemia COVID-19. Evaluamos la prevalencia de trastornos mentales y factores asociados durante la primera oleada de la pandemia en sanitarios españoles.

Métodos

Se invitó a todos los trabajadores de 18 instituciones sanitarias españolas (6 CCAA) a encuestas en línea evaluando características individuales, estado de infección y exposición a COVID-19 y salud mental (5 Mayo – 7 Septiembre, 2020). Reportamos: probables trastornos mentales actuales (Trastorno depresivo mayor TDD [PHQ-8≥10], Trastorno de ansiedad generalizada TAG [GAD-7≥10], Ataques de pánico, Trastorno de estrés postraumático TEP [PCL-5≥7]; y Trastorno por uso de sustancias TUS [CAGE-AID≥2]. La interferencia funcional grave (Escala de Discapacidad de Sheehan) identificó los probables trastornos “discapacitantes”.

Resultados

Participaron 9.138 sanitarios. Prevalencia de cribado positivo: 28,1% TDD; 22,5% TAG, 24,0% Pánico; 22,2% PTE; y 6,2% TUS. En general, el 45,7% presentó algún trastorno mental actual y el 14,5% algún trastorno discapacitante. Los sanitarios con trastornos mentales previos tuvieron el doble de prevalencia que aquellos sin patología mental previa. Ajustando por todas las variables, el trastorno mental incapacitante se asoció positivamente con: trastornos previos (TUS: OR=5.74; 95%CI 2.53-13.03; Ánimo: OR=3.23; 95%CI:2.27-4.60; Ansiedad: OR=3,03; IC 95%: 2,53-3,62); edad 18-29 años (OR=1,36; IC 95%: 1,02-1,82); atender “siempre” a pacientes COVID-19 (OR=5,19; IC 95%: 3,61-7,46), género femenino (OR=1,58; IC 95%: 1,27-1,96) y haber estado en cuarentena o aislado (OR=1,60; IC 95%: 1,31-1,95).

Conclusiones

Uno de cada 7 sanitarios españoles presentaron un probable trastorno mental discapacitante durante la primera oleada de COVID-19. Aquéllos con trastornos mentales alguna vez antes de la pandemia, los que están expuestos con frecuencia a pacientes con COVID-19, los infectados o en cuarentena / aislados, las mujeres y las enfermeras auxiliares deben considerarse grupos que necesitan seguimiento y apoyo de su salud mental.

Palabras clave: Pandemia de COVID-19, Trabajadores de la salud, Trastornos mentales, Necesidad de atención, Discapacidad, Salud mental adversa

Introduction

COVID-19 represents a major health challenge worldwide and several populations may experience adverse mental health related to the COVID-19 pandemic.1, 2 Among them, front-line healthcare workers are considered an extremely at risk population because of their direct exposure to infected patients, the limited availability of protective equipment, and the increased workload related to the pandemic. Compared to the general community, healthcare workers have about 12 times more risk for a positive COVID-19 test.3 Although with noticeable regional and international variations, it is estimated that 10–20% of all COVID-19 diagnoses occur in this population segment.4, 5 In addition to the risk of contagion and insufficiency of equipment and health services preparedness there is great concern for the potential impact (acute and longer term) on the mental health of healthcare workers.

Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses including studies on health care workers have documented that the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with increased depression, anxiety, insomnia, and burnout, as well as other adverse psychosocial outcomes. Luo et al.,6 estimated that a quarter of healthcare workers suffered from anxiety (26%), depression (25%), and that about a third suffered substantial stress. Similar figures were reported in other systematic reviews.7, 8, 9 In Spain, a number of studies have been carried out to assess mental health of healthcare workers during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 In general, results are consistent with international data, showing high levels of anxiety, depression and stress symptoms.

Differences in study design, sample size as well as variation in the assessment of adverse mental health hamper comparisons across studies. Importantly, current studies have limited value when it comes to assessing the needs for care associated with the impact of COVID-19 among healthcare workers. There is a necessity of credible and actionable indicators of mental disorders and their impact which more directly enable policy makers to allocate adequate resources when planning interventions.

Here we aimed to estimate the prevalence of clinically significant mental disorders among Spanish healthcare professionals during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (March-July, 2020) using a representative sample and well-validated screeners of common mental disorders. Specifically, our objectives were to estimate (1) prevalence of specific mental disorders, any such disorder, and any disabling disorder both in the total sample of healthcare professionals and in subsamples of those with/without prior lifetime mental disorders; and (2) associations of individual and professional characteristics, COVID-19 infection status, and COVID-19 exposure with these mental disorders.

Methods

Study design, population and sampling

A multicenter, observational cohort study of healthcare workers was carried out in a convenience sample of 18 health care institutions from 6 Autonomous Communities in Spain (i.e., Andalusia, the Basque Country, Castile and Leon, Catalonia, Madrid, and Valencia). Institutions were selected to reflect the geographical and sociodemographic variability in Spain; most participating centers came from regions with high COVID-19 caseloads. Here we report on the baseline assessment of the cohort, which consists of de-identified web-based self-report surveys administered soon after the first COVID-19 outbreak in Spain. Data collection started at the time of stabilization in the number of new cases in Spain, but when health institutions, particularly hospitals, were under very high demand pressures (May 5 – September 7, 2020).

In each participating health care institution, institutional representatives invited all employed hospital workers to participate using the hospitals’ administrative email distribution lists (i.e., census sampling). No further advertising of the survey was done and no incentives were offered for participation. The invitation email included an anonymous link to access the web-based survey platform (qualtrics.com).

Informed consent was obtained from all participants at the first survey page. Up to two reminder emails were sent within a 2–4 weeks period after the initial invitation. At the end of the survey, all participants were provided with a detailed list of local mental healthcare resources, including coordinates to nearby emergency care for respondents with a 30-day suicide attempt.

Measures

Current mental disorders

-

-

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD): evaluated with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8). We used the Spanish version of the PHQ-816 with the cut-off point of 10 or higher of the sum score to indicate current MDD. The PHQ-8 shows high reliability (>0.8) and good diagnostic accuracy for Major Depressive Disorder (AUC > 0.90).17

-

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): evaluated with the seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7), which has a good performance to detect anxiety (AUC > 0.8).18 We used the Spanish version of the GAD-719 and considered the cut-off point of 10 or higher to indicate a current GAD.

-

-

Panic attacks: the number of panic attacks in the 30 days prior to the interview was assessed with an item from the World Mental Health-International College Student-WMH-ICS.20, 21 A dichotomous variable was created to indicate the presence of panic attacks.

-

-

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): assessed using the 4-item version of the PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)22, 23 which generates diagnoses that closely parallel those of the full PCL-5 (AUC > 0.9), making it well-suited for screening.23 We used the Spanish version of the questionnaire,24 and considered a cut-off point of 7 to indicate current PTSD.

-

-

Substance Use Disorder (SUD): evaluated with the CAGE-AID questionnaire, that consists of 4 items focusing on Cutting down, Annoyance by criticism, Guilty feeling, and Eye-openers. The CAGE-AID has been proved useful in helping to make a diagnosis of alcoholism25, 26, 27 and Substance Use Disorder.28 The questionnaire has been adapted into Spanish. A cut-off point of 2 was considered to indicate current SUD.29

-

-

Disabling mental disorder: a mental disorder was considered “disabling” if the participant reported severe role impairment during the past 12 months according to an adapted version of the Sheehan Disability Scale.30, 31, 32 A 0–10 visual analog scale was used to rate the degree of impairment for four domains: home management/chores, work, close personal relationships, and social life. The scale was labeled as no interference (0), mild (1–3), moderate (4–6), severe (7–9), and very severe (10) interference. Severe role impairment was defined as having a 7–10 rating.33, 34, 35

-

-

Prior lifetime mental disorders: lifetime mental disorders prior to the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak were assessed using a checklist based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) that screens for self-reported lifetime depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, panic attacks, alcohol and drug use disorders, and “other” mental disorders.

COVID-19 exposure and infection status

We assessed the frequency of direct exposure to COVID-19 infected patients during professional activity using one 5-level Likert type item, ranging from “none of the time” to “all of the time. We defined frontline healthcare workers those reporting being exposed “all of the time” or “most of the time” to COVID-19 patients. We assessed COVID-19 infection status asking whether the respondent had been hospitalized for COVID-19 infection and/or had a positive COVID-19 test or medical diagnosis not requiring hospitalization. We also asked whether the respondent had been in isolation or quarantine because of exposure to COVID-19 infected person(s), and whether s/he had close ones infected with COVID-19.

Individual characteristics

We assessed: age; gender; country of birth; marital status; having children in care; living situation; and profession into 5 categories: medical doctors, nurses, auxiliary nurses, other professions involved in patient care (i.e., midwives; dentists or odontologists; pharmaceutical, laboratory, or radiology technicians; psychologists, physiotherapists, social workers, patient transport), and other professions not involved in patient care (i.e., administrative and management personnel, logistic support [e.g. food, maintenance, supplies], research-only personnel).

Ethical considerations

The study complies with the principles established by national and international regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki and the Code of Ethics. The study protocol was approved by the IRB Parc de Salut Mar (2020/9203/I) and by the corresponding IRBs of all the participating centers. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04556565).

Statistical analysis

Analyses were restricted to the n = 9146 respondents who completed all mental health items of the questionnaire. An additional n = 8 respondents were excluded because they did not identify with neither male nor female gender. In order to improve representativeness, observed data were weighted using raking procedure to reproduce marginal distributions of gender, age and professional category of healthcare personnel in each participating institution, as well as distribution of personnel across institutions.

To optimize survey response time, the Sheehan disability scale was assessed in a random 60% of the sample. Median missingness per variable was less than 1%. All missing item-level data from the Sheehan scale and from all other variables included in the analysis were handled using multiple imputation (MI) by chained equations with 40 imputed datasets and 10 iterations.

Distribution of individual characteristics and COVID-19 infection and exposure variables were obtained for the whole sample as weighted percentage and standard error. Prevalence estimates of specific current mental disorders, any current mental disorder, and any disabling disorder were estimated, overall and stratified by individual characteristics. Chi-square tests from MI pooled using Rubin's rule were used to determine significant differences across strata. Adjustment for multiple comparisons was performed using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure36 with a false discovery rate of 5%. Bivariable associations between each individual characteristic and current mental disorders and severe mental disorder were estimated for the overall sample, and separately for individuals with and without a history of prior lifetime mental disorders. Odds ratios (OR) and MI-based 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each characteristic were calculated with logistic regression, adjusted by week of survey and health center membership. Finally, multivariable associations between all COVID-19 exposure and infection status, individual characteristics and current and disabling mental disorders were estimated, stratifying by prior lifetime mental disorders.

MI were carried out using package mice from R.37, 38 Analyses were performed using R v3.4.239 and SAS v9.4.40

Results

Survey response

A total of 9138 healthcare workers participated in the surveys. The response rate is difficult to estimate given that the survey view rate (i.e., the proportion of hospital workers that opened the invitation email) is unknown, except for one hospital (26.4%). The survey participation rate (i.e., those that agreed to participate divided by those that responded to the informed consent on the first survey page) was 89.0%, and the survey completion rate (i.e., those that completed the survey among those that agreed to participate) was 80.8%. When the denominator used to calculate the response rate is the total number of health care workers listed in the email distribution list or the total number of healthcare workers employed as provided by the hospital representatives, the survey response adjusted by achieved sample size is 12.5% (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Prevalence of current mental disorders:

The first two columns of Table 1 show the size and weighted distribution of the sample studied. Healthcare professionals were mostly female (77.3%), the larger age group was 30–49 years (45.8%), just over half were married (53.0%), four out of ten were living with children (41.4%), and 57.2% were living in an apartment. About a fourth (26.4%) were physicians, and 30.6% were nurses, and the majority were working in a hospital (54.1%). Almost 80% of participants were directly involved in patient care, although less than a half (43.6%) were directly exposed to COVID-19 patients all or most of the time (i.e., frontline workers). Almost a fifth (17.4%) had COVID-19, 13.8% had their spouse/partner, children or parents infected with COVID-19, and up to 25.5% had been isolated or quarantined. An important proportion (41.6%) reported pre-pandmic lifetime mental disorder(s).

Table 1.

Prevalence of current probable mental disorders among Spanish healthcare workers, according to individual characteristics, COVID-19 exposure, and prior lifetime disorders. MINCOVID study (N = 9138) (absolute numbers and weighted proportions).

| Na | %b | Current MDD (n = 2554) | Current GAD (n = 2007) | Current panic attacks (n = 2064) | Current PTSD (n = 1946) | Current substance use disorder (n = 569) | Any current mental disorder (n = 4118) | Any current disabling mental disorder (n = 1278) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %b (SE) | %b (SE) | %b (SE) | %b (SE) | %b (SE) | %b (SE) | %b (SE) | |||

| 28.1 (0.5)* | 22.5 (0.4)* | 24.0 (0.5)* | 22.2 (0.4)* | 6.2 (0.3)* | 45.7 (0.5)* | 14.5 (0.5)* | |||

| Gender | |||||||||

| -Male | 1766 | 22.7 (0.4)* | 20.2 (0.9)* | 17.1 (0.8)* | 17.6 (0.9)* | 15.6 (0.8)* | 8.3 (0.6)* | 36.4 (1.1)* | 10.7 (0.9)* |

| -Female | 7372 | 77.3 (0.4) | 30.4 (0.6) | 24.1 (0.5) | 25.8 (0.5) | 24.2 (0.5) | 5.6 (0.3) | 48.5 (0.6) | 15.6 (0.6) |

| Age | |||||||||

| -18–29 years | 1188 | 10.8 (0.3)* | 33.7 (1.5)* | 27.8 (1.4)* | 32.1 (1.5)* | 22.9 (1.3)* | 9.6 (1.0)* | 54.7 (1.6)* | 16.6 (1.4)* |

| -30–49 year | 4252 | 45.8 (0.5) | 30.2 (0.7) | 24.9 (0.7) | 25.6 (0.7) | 24.1 (0.7) | 7.0 (0.4) | 49.2 (0.8) | 15.4 (0.7) |

| -50 years or more | 3698 | 43.4 (0.5) | 24.4 (0.7) | 18.7 (0.6) | 20.2 (0.7) | 20.1 (0.6) | 4.5 (0.3) | 39.8 (0.8) | 13.0 (0.7) |

| Country of birth | |||||||||

| -Spain | 8677 | 95.4 (0.2)* | 27.7 (0.5)* | 22.5 (0.5) | 23.6 (0.5)* | 22.2 (0.5) | 6.1 (0.3) | 45.4 (0.5)* | 14.4 (0.5) |

| -Other | 461 | 4.6 (0.2) | 36.0 (2.4) | 22.5 (2.1) | 31.4 (2.4) | 22.5 (2.1) | 7.7 (1.3) | 53.3 (2.5) | 15.3 (2.1) |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| -Single, divorced or legally separated, or widowed | 4465 | 47.0 (0.5)* | 30.8 (0.7)* | 22.7 (0.6) | 26.5 (0.7)* | 23.1 (0.6) | 7.6 (0.4)* | 48.9 (0.8)* | 15.9 (0.7)* |

| -Married | 4673 | 53.0 (0.5) | 25.6 (0.6) | 22.4 (0.6) | 21.7 (0.6) | 21.5 (0.6) | 5.0 (0.3) | 42.9 (0.7) | 13.2 (0.7) |

| Having children in care | |||||||||

| -Younger (<12 ys) children in care | 2377 | 25.9 (0.5)* | 27.9 (0.9)* | 24.4 (0.9)* | 23.6 (0.9)* | 22.3 (0.9) | 4.7 (0.4)* | 46.6 (1.1)* | 14.5 (0.9) |

| -Children in care, but >12ys | 1328 | 15.5 (0.4) | 24.7 (1.2) | 18.1 (1.0) | 21.4 (1.1) | 21.0 (1.1) | 5.7 (0.6) | 42.0 (1.4) | 12.7 (1.0) |

| -No children in care | 5433 | 58.6 (0.5) | 29.1 (0.6) | 22.8 (0.6) | 24.8 (0.6) | 22.5 (0.6) | 7.0 (0.4) | 46.4 (0.7) | 15.0 (0.6) |

| Living situation | |||||||||

| -House | 3724 | 42.4 (0.5)* | 27.6 (0.7) | 23.1 (0.7) | 22.8 (0.7) | 23.3 (0.7)* | 4.8 (0.4)* | 44.6 (0.8) | 14.1 (0.7) |

| -Apartment | 5383 | 57.2 (0.5) | 28.4 (0.6) | 22.0 (0.6) | 24.8 (0.6) | 21.3 (0.6) | 7.2 (0.4) | 46.5 (0.7) | 14.7 (0.7) |

| -Other | 31 | 0.4 (0.1) | 37.0 (8.5) | 31.9 (8.1) | 32.9 (8.5) | 41.7 (8.7) | 6.8 (4.7) | 53.1 (9.0) | 23.6 (8.9) |

| Profession | |||||||||

| -Physician | 2953 | 26.4 (0.5)* | 22.4 (0.9)* | 17.0 (0.8)* | 14.3 (0.7)* | 13.8 (0.7)* | 6.8 (0.5)* | 35.9 (1.0)* | 9.6 (0.7)* |

| -Nurse | 2746 | 30.6 (0.5) | 31.2 (0.9) | 25.6 (0.8) | 24.2 (0.8) | 25.1 (0.8) | 5.5 (0.4) | 50.4 (1.0) | 16.9 (0.9) |

| -Auxiliary nurse | 881 | 13.6 (0.4) | 38.9 (1.4) | 30.8 (1.3) | 39.6 (1.4) | 35.1 (1.4) | 4.9 (0.6) | 59.5 (1.4) | 19.8 (1.4) |

| -Other profession involved in patient care | 960 | 9.2 (0.3) | 21.7 (1.4) | 17.2 (1.3) | 21.6 (1.5) | 18.1 (1.3) | 7.8 (0.9) | 40.0 (1.7) | 11.3 (1.3) |

| -Other profession not involved in patient care | 1598 | 20.3 (0.4) | 26.5 (1.0) | 22.0 (1.0) | 26.8 (1.1) | 22.1 (1.0) | 6.6 (0.6) | 44.9 (1.2) | 15.0 (1.1) |

| Workplace setting | |||||||||

| -Hospital | 5207 | 54.1 (0.5)* | 28.9 (0.7)* | 22.7 (0.6) | 25.1 (0.6)* | 23.2 (0.6)* | 6.8 (0.4)* | 47.1 (0.7)* | 14.9 (0.6) |

| -Primary Care | 2772 | 35.2 (0.5) | 27.9 (0.8) | 22.8 (0.8) | 22.8 (0.8) | 21.6 (0.7) | 5.2 (0.4) | 44.5 (0.9) | 14.0 (0.9) |

| -Others | 1159 | 10.7 (0.3) | 24.7 (1.4) | 20.6 (1.3) | 22.0 (1.4) | 19.2 (1.3) | 6.5 (0.8) | 43.0 (1.6) | 13.8 (1.4) |

| Frontline work during COVID-19 | |||||||||

| -Frontline | 4180 | 43.6 (0.5)* | 36.2 (0.8)* | 29.7 (0.7)* | 30.3 (0.8)* | 28.6 (0.7)* | 6.4 (0.4) | 54.9 (0.8)* | 18.3 (0.8)* |

| -Not-frontline | 4958 | 56.4 (0.5) | 21.8 (0.6) | 16.9 (0.5) | 19.1 (0.6) | 17.3 (0.5) | 6.0 (0.3) | 38.6 (0.7) | 11.6 (0.6) |

| Frequency of direct exposure to COVID-19 patients | |||||||||

| -All of the time | 2256 | 23.0 (0.5)* | 39.7 (1.1)* | 34.3 (1.1)* | 32.5 (1.1)* | 32.4 (1.0)* | 7.1 (0.6) | 58.7 (1.1)* | 18.8 (1.1)* |

| -Most of the time | 1924 | 20.7 (0.4) | 32.3 (1.1) | 24.7 (1.0) | 27.9 (1.1) | 24.5 (1.0) | 5.7 (0.6) | 50.7 (1.2) | 17.7 (1.1) |

| -Some of the time | 2617 | 30.2 (0.5) | 26.1 (0.9) | 20.3 (0.8) | 22.4 (0.8) | 22.3 (0.8) | 6.1 (0.5) | 44.7 (1.0) | 13.4 (0.9) |

| -A little of the time | 1183 | 14.1 (0.4) | 19.1 (1.1) | 14.7 (1.0) | 16.1 (1.1) | 13.6 (1.0) | 6.8 (0.7) | 34.5 (1.4) | 11.1 (1.0) |

| -None of the time | 1158 | 12.0 (0.4) | 14.4 (1.1) | 11.3 (1.0) | 14.2 (1.1) | 8.9 (0.9) | 4.8 (0.7) | 28.1 (1.4) | 7.6 (1.0) |

| COVID-19 infection history | |||||||||

| -Having been hospitalized for COVID-19 | 112 | 1.2 (0.1)* | 38.4 (4.6)* | 33.9 (4.5)* | 27.7 (4.3)* | 25.5 (4.1) | 7.8 (2.6)* | 55.6 (4.7)* | 24.8 (4.7)* |

| -Positive COVID-19 test or medical COVID-19c | 1576 | 16.2 (0.4) | 32.8 (1.2) | 25.6 (1.1) | 26.5 (1.2) | 23.3 (1.1) | 4.6 (0.6) | 49.2 (1.3) | 16.4 (1.1) |

| -None of the above | 7450 | 82.6 (0.4) | 27.0 (0.5) | 21.8 (0.5) | 23.4 (0.5) | 22.0 (0.5) | 6.5 (0.3) | 44.9 (0.6) | 14.0 (0.6) |

| Isolation or quarantine because of COVID-19 | |||||||||

| -Having been isolated or quarantined | 2444 | 25.5 (0.5)* | 33.9 (1.0)* | 26.0 (0.9)* | 27.6 (0.9)* | 24.3 (0.9)* | 6.1 (0.5) | 51.8 (1.1)* | 17.9 (1.0)* |

| -Not having been isolated or quarantined | 6694 | 74.5 (0.5) | 26.1 (0.5) | 21.3 (0.5) | 22.7 (0.5) | 21.5 (0.5) | 6.2 (0.3) | 43.7 (0.6) | 13.3 (0.6) |

| Close ones infected with COVID-19 | |||||||||

| -Partner, children, or parents | 1396 | 13.8 (0.4)* | 35.7 (1.4)* | 28.7 (1.3)* | 25.6 (1.3) | 26.2 (1.2)* | 5.7 (0.7)* | 51.4 (1.4)* | 17.1 (1.2) |

| -Other family, friends or othersd | 5532 | 58.5 (0.5) | 27.6 (0.6) | 22.2 (0.6) | 24.0 (0.6) | 21.4 (0.6) | 6.8 (0.4) | 46.0 (0.7) | 14.1 (0.6) |

| -None of the above | 2210 | 27.7 (0.5) | 25.4 (0.9) | 20.1 (0.8) | 23.1 (0.9) | 21.9 (0.8) | 5.0 (0.5) | 42.5 (1.0) | 14.1 (0.9) |

| Lifetime mental disorders before onset COVID-19 outbreak | |||||||||

| -Lifetime mood disorder | 1009 | 11.2 (0.3) * | 50.1 (1.6)* | 39.2 (1.5) * | 38.6 (1.6) * | 36.2 (1.5) * | 10.9 (1.0) * | 70.4 (1.4) * | 31.1 (1.9) * |

| -No lifetime mood disorder | 8129 | 88.8 (0.3) | 25.3 (0.5) | 20.4 (0.5) | 22.1 (0.5) | 20.5 (0.5) | 5.6 (0.3) | 42.6 (0.6) | 12.4 (0.5) |

| -Lifetime anxiety disorder | 3241 | 35.9 (0.5) * | 40.0 (0.9) * | 32.6 (0.8) * | 38.4 (0.9) * | 30.9 (0.8) * | 9.5 (0.5) * | 63.6 (0.9) * | 21.9 (1.0) * |

| -No lifetime anxiety disorder | 5897 | 64.1 (0.5) | 21.4 (0.5) | 16.9 (0.5) | 15.9 (0.5) | 17.4 (0.5) | 4.3 (0.3) | 35.8 (0.6) | 10.3 (0.5) |

| -Lifetime substance use disorder | 124 | 1.4 (0.1) * | 61.0 (4.4) * | 41.8 (4.4) * | 40.2 (4.6) * | 42.0 (4.4) * | 62.8 (4.4) * | 90.1 (2.8) * | 30.5 (4.9) * |

| -No lifetime substance use disorder | 9015 | 98.6 (0.1) | 27.6 (0.5) | 22.3 (0.4) | 23.7 (0.5) | 22.0 (0.4) | 5.4 (0.2) | 45.1 (0.5) | 14.3 (0.5) |

| -Other lifetime mental disorder | 257 | 2.8 (0.2) * | 38.8 (3.1) * | 25.4 (2.7) | 29.2 (2.9) | 28.1 (2.8) * | 9.5 (1.9) * | 58.1 (3.1) * | 26.0 (3.5) * |

| -No other lifetime mental disorder | 8881 | 97.2 (0.2) | 27.8 (0.5) | 22.4 (0.4) | 23.8 (0.5) | 22.1 (0.4) | 6.1 (0.3) | 45.4 (0.5) | 14.2 (0.5) |

| -Any lifetime mental disorder | 3771 | 41.6 (0.5)* | 39.5 (0.8)* | 31.3 (0.8)* | 36.1 (0.8)* | 30.0 (0.8)* | 9.2 (0.5)* | 62.3 (0.8)* | 21.6 (0.9)* |

| -No lifetime mental disorder | 5367 | 58.4 (0.5) | 20.0 (0.6) | 16.3 (0.5) | 15.3 (0.5) | 16.7 (0.5) | 4.0 (0.3) | 33.9 (0.7) | 9.4 (0.5) |

| Number of prior lifetime mental disorders | |||||||||

| -Zero | 5367 | 58.4 (0.5)* | 20.0 (0.6)* | 16.3 (0.5)* | 15.3 (0.5)* | 16.7 (0.5)* | 4.0 (0.3)* | 33.9 (0.7)* | 9.4 (0.5)* |

| -Exactly one | 2999 | 33.0 (0.5) | 35.4 (0.9) | 27.9 (0.8) | 33.7 (0.9) | 27.0 (0.8) | 7.3 (0.5) | 58.1 (0.9) | 18.0 (0.9) |

| -Two or more | 771 | 8.6 (0.3) | 55.0 (1.8) | 44.1 (1.8) | 45.6 (1.9) | 41.4 (1.8) | 16.6 (1.3) | 78.0 (1.5) | 35.3 (2.2) |

Pooled Chi-square test from multiple imputations statistically significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons with Benjamini-Hochberg (false discovery rate 0.05).

Unweighted numbers.

Weighted percentage (using post-stratification weights obtained with raking procedure).

The category “positive COVID-19 test or medical COVID-19 diagnosis” excludes those having been hospitalized for COVID-19.

The category “other family, friends or others” excludes having a partner, children, or parents infected with COVID-19.

Also in Table 1, the prevalence of current mental disorders is presented according to the above variables. Overall, 28.1% met criteria for Major Depressive Disorder, between 22.2% and 24.0% met criteria for anxiety disorders (GAD, Panic attacks, or PTSD), and 6.2% met criteria for substance use disorder. In all, almost half of the sample (45.7%) met criteria for current mental disorder and about one in seven (14.5%) had a current disabling mental disorder.

The prevalence of any current mental disorder was significantly higher among healthcare workers with female gender, younger age, not born in Spain, not being married, or living with children less than 12 years of age or not having children at home. Auxiliary nurses and nurses showed the highest prevalence of current mental disorders (59.5% and 50.4%, respectively). There was a clear positive trend with higher exposure to COVID-19 patients, and those having the disease – in particular those 112 professionals who had been hospitalized for COVID-19, having been isolated or quarantined, and whose parents, children or partner were infected with COVID-19. Prior lifetime mental disorders were strongly associated with presenting current mental disorder (especially those reporting previous substance use disorder or depression). The higher the number of prior lifetime mental disorders reported, the more likely the prevalence of any current disorder. Similar prevalence differences were found when considering current disabling mental disorders.

Current mental disorders according to prior lifetime mental disorders

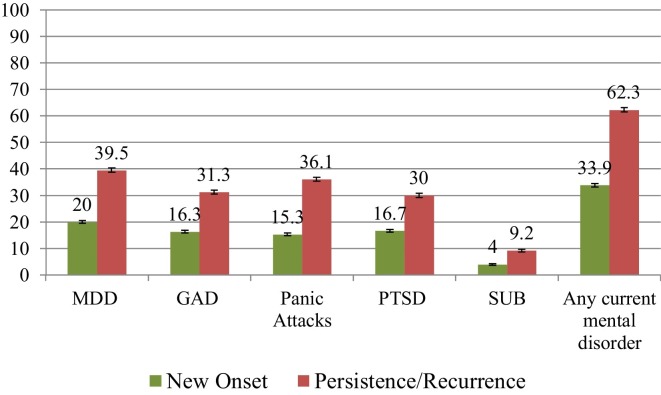

Fig. 1 shows current prevalence of mental disorders according to pre-COVID-19 pandemic lifetime mental disorders. Prevalence was consistently lower among workers without prior mental disorders (new onset), i.e., approximately half than among workers with prior mental disorders (persistent/relapsing).

Figure 1.

Current prevalence of probable mental disorders among Spanish healthcare workers during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to pre-pandemic lifetime mental disorders. MINDCOVID study (n = 9138).

Green bar: workers with no pre-pandemic mental disorders (new onset); Red Bar: workers with lifetime history of mental disorders (persistence/recurrence).

MDD: Major Depressive Disorder; GAD: Generalized Anxiety Disorder; PTSD: Post-Stress Traumatic Disorder; SUB: Substance Use Disorder.

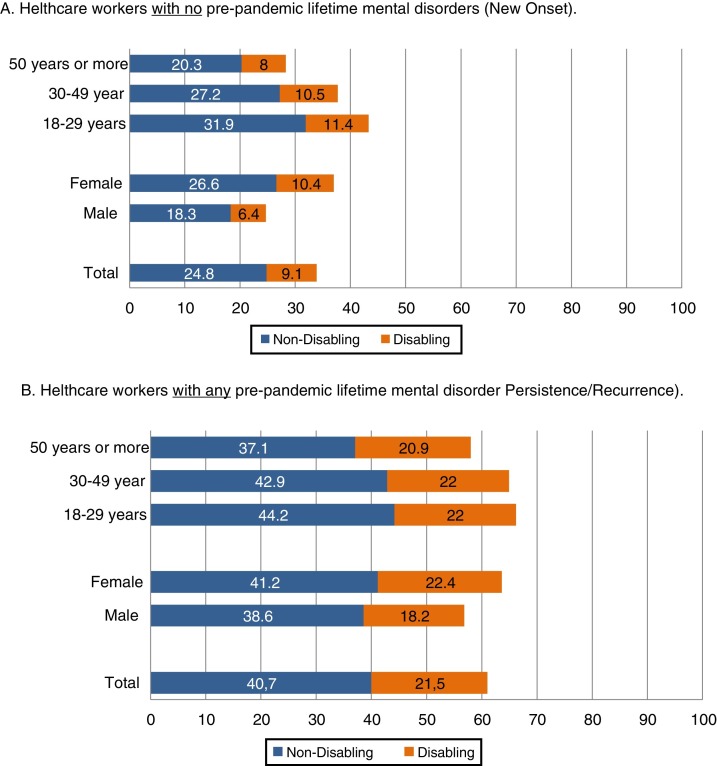

Fig. 2 shows current prevalence of any mental disorders (both disabling and non-disabling), according to pre-COVID-19 pandemic prior lifetime mental disorders. Among workers without prior mental disorders, the prevalence of any mental disorder (new onset) was almost 34% and one in four of those were disabling mental disorders (Fig. 2A). Among healthcare workers with any prior lifetime disorder, the prevalence of current disorders (persistence/relapse) was much higher (61%) and more frequently disabling (i.e., one in three) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Current prevalence of any probable mental disorders (disabling and non-disabling) among Spanish healthcare workers during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, according the pre-pandemic lifetime mental disorders and individual characteristics. MINDCOVID study (n = 9138).

Factors associated with current mental disorders

Table 2 shows bivariate associations of individual characteristics, personal COVID-19 exposure and prior lifetime mental disorders with any current mental disorder and with any current disabling mental disorder. The first two columns present the associations for the overall sample (n = 9138) that had been presented in Table 1 in the form of Odds Ratios, once adjusting by week of the survey and by healthcare center. Table 2 also shows these associations, stratifying by prior lifetime mental disorders. Columns 3–4 present data for those with no mental disorders prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and columns 5–6 refer to those reporting mental disorders before the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. In general, all the above-mentioned variables under study with any current (disabling) mental disorders were significantly associated with both new onset and persistence/relapse mental disorders. However, the association of hospitalization due to COVID-19 with any current disabling disorder was only significant for those with previous mental disorders. Among those with previous mental disorders, previous SUD and previous depression were most strongly associated with current persisting/relapsing mental disorders.

Table 2.

Bivariate associations between individual characteristics, COVID-19 exposure, and pre-pandemic lifetime (LT) mental disorders with any probable current mental disorders and current disabling. Spanish healthcare workers, MINDCOVID study (N=9138).

| ALL (n = 9138) |

No prior LT mental disorders (new onset) (n = 5367) |

Prior LT mental disorder (persistence relapse) (n = 3771) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any current mental disorder (n = 4118) | Any current disabling mental disorder (n = 1278) | Any current mental disorder (n = 1818) | Any current disabling mental disorder (n = 485) | Any current mental disorder (n = 2300) | Any current disabling mental disorder (n = 793) | |

| OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

| Gender – female (vs. male) | 1.60 (1.44–1.78)* | 1.77 (1.46–2.14)* | 1.74 (1.50–2.02)* | 1.96 (1.43–2.70)* | 1.32 (1.12–1.56)* | 1.45 (1.11–1.88)* |

| Age | ||||||

| -18–29 years | 1.77 (1.53–2.05)* | 1.61 (1.27–2.03)* | 1.89 (1.54–2.34)* | 1.73 (1.17–2.56)* | 1.36 (1.09–1.69)* | 1.22 (0.89–1.67) |

| -30–49 year | 1.48 (1.35–1.62)* | 1.39 (1.19–1.63)* | 1.55 (1.37–1.76)* | 1.51 (1.19–1.91)* | 1.35 (1.17–1.57)* | 1.25 (1.00–1.57) |

| -50 years or more | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Country of Birth – Spain (vs. Other) | 0.74 (0.60–0.91)* | 0.85 (0.61–1.19) | 0.80 (0.60–1.06) | 0.93 (0.54–1.62) | 0.69 (0.49–0.97)* | 0.83 (0.51–1.35) |

| Marital status – married (vs. single, divorced or legally separated, or widowed) | 0.81 (0.74–0.88)* | 0.77 (0.67–0.89)* | 0.88 (0.78–0.99)* | 0.88 (0.70–1.10) | 0.86 (0.75–0.99)* | 0.82 (0.67–1.00) |

| Having children in care | ||||||

| -Younger (<12 ys) children in care | 1.04 (0.94–1.15) | 1.01 (0.86–1.18) | 1.17 (1.02–1.34)* | 1.18 (0.91–1.51) | 1.00 (0.85–1.18) | 0.96 (0.76–1.21) |

| -Children in care, but >12ys | 0.86 (0.76–0.97)* | 0.81 (0.66–0.99)* | 0.89 (0.75–1.06) | 0.80 (0.58–1.10) | 0.90 (0.74–1.10) | 0.89 (0.66–1.18) |

| -No children in care | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Living situation | ||||||

| -House | 0.78 (0.38–1.61) | 0.53 (0.19–1.43) | 0.74 (0.23–2.40) | 0.45 (0.09–2.29) | 1.16 (0.45–3.00) | 0.79 (0.21–3.00) |

| -Apartment | 0.85 (0.41–1.75) | 0.56 (0.20–1.53) | 0.80 (0.25–2.57) | 0.47 (0.09–2.40) | 1.17 (0.45–3.02) | 0.78 (0.20–3.01) |

| -Other | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Profession | ||||||

| -Physician | 0.63 (0.55–0.71)* | 0.50 (0.40–0.62)* | 0.66 (0.55–0.79)* | 0.47 (0.33–0.68)* | 0.64 (0.52–0.78)* | 0.53 (0.39–0.73)* |

| -Nurse | 1.17 (1.03–1.32)* | 1.16 (0.95–1.42) | 1.41 (1.19–1.68)* | 1.29 (0.94–1.77) | 1.03 (0.85–1.26) | 1.10 (0.83–1.45) |

| -Auxiliary nurse | 1.74 (1.48–2.03)* | 1.73 (1.35–2.22)* | 1.81 (1.45–2.26)* | 1.62 (1.09–2.41)* | 1.72 (1.33–2.23)* | 1.79 (1.26–2.56)* |

| -Other profession involved in patient care | 0.78 (0.66–0.93)* | 0.65 (0.48–0.88)* | 0.71 (0.55–0.91)* | 0.60 (0.37–0.98)* | 0.88 (0.67–1.15) | 0.70 (0.47–1.06) |

| -Other profession not involved in patient care | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Workplace setting | ||||||

| -Hospital | 1.10 (0.95–1.28) | 1.08 (0.85–1.38) | 1.06 (0.86–1.30) | 1.07 (0.71–1.61) | 1.15 (0.91–1.47) | 1.14 (0.81–1.60) |

| -Primary Care | 1.14 (0.95–1.36) | 1.14 (0.82–1.57) | 1.22 (0.94–1.58) | 1.24 (0.73–2.10) | 1.08 (0.82–1.44) | 1.11 (0.71–1.74) |

| -Other | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Frontline work during COVID-19 | 1.82 (1.66–1.99)* | 2.00 (1.72–2.32)* | 1.97 (1.73–2.23)* | 2.44 (1.89–3.14)* | 1.77 (1.54–2.04)* | 1.86 (1.53–2.27)* |

| Frequency of direct exposure to COVID-19 patients | ||||||

| -All of the time | 3.30 (2.78–3.91)* | 3.88 (2.85–5.28)* | 4.37 (3.37–5.68)* | 5.78 (3.37–9.94)* | 3.11 (2.41–4.01)* | 3.68 (2.47–5.47)* |

| -Most of the time | 2.53 (2.14–3.01)* | 3.27 (2.39–4.47)* | 3.04 (2.32–3.97)* | 4.35 (2.48–7.64)* | 2.42 (1.89–3.10)* | 3.04 (2.04–4.54)* |

| -Some of the time | 2.01 (1.71–2.37)* | 2.24 (1.63–3.07)* | 2.49 (1.93–3.21)* | 2.70 (1.54–4.74)* | 1.88 (1.48–2.38)* | 2.21 (1.49–3.29)* |

| -A little of the time | 1.31 (1.09–1.58)* | 1.57 (1.13–2.20)* | 1.44 (1.08–1.91)* | 1.74 (0.96–3.16) | 1.42 (1.08–1.86)* | 1.73 (1.11–2.70)* |

| -None of the time | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| COVID-19 infection history | ||||||

| -Having been hospitalized for COVID-19 | 1.41 (0.96–2.06) | 2.05 (1.23–3.41)* | 1.05 (0.59–1.85) | 1.83 (0.82–4.09) | 1.65 (0.90–3.02) | 2.18 (1.04–4.57)* |

| -Positive COVID-19 test or medical COVID-19 diagnosisa | 1.07 (0.95–1.20) | 1.12 (0.93–1.34) | 1.03 (0.88–1.21) | 1.10 (0.82–1.48) | 1.11 (0.92–1.34) | 1.14 (0.88–1.47) |

| -None of the above | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Having been isolated or quarantined because of COVID-19 | 1.35 (1.22–1.49)* | 1.52 (1.31–1.77)* | 1.27 (1.10–1.45)* | 1.52 (1.20–1.92)* | 1.41 (1.20–1.65)* | 1.56 (1.25–1.94)* |

| Close ones infected with COVID-19 | ||||||

| -Partner, children, or parents | 1.25 (1.08–1.44)* | 1.19 (0.95–1.48) | 1.51 (1.25–1.84)* | 1.41 (1.01–1.96)* | 0.99 (0.79–1.25) | 0.97 (0.70–1.34) |

| -Other family, friends or othersb | 1.09 (0.98–1.20) | 0.98 (0.83–1.16) | 1.24 (1.08–1.42)* | 1.03 (0.78–1.35) | 0.95 (0.81–1.11) | 0.90 (0.71–1.14) |

| -None of the above | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Lifetime mood disorder before onset COVID-19 outbreak | 3.18 (2.75–3.68)* | 4.88 (4.02–5.94)* | n.a. | n.a. | 1.61 (1.38–1.89)* | 2.41 (1.95–2.98)* |

| Lifetime anxiety disorder before onset COVID-19 outbreak | 3.15 (2.87–3.45)* | 3.72 (3.19–4.34)* | n.a. | n.a. | 1.52 (1.26–1.84)* | 1.44 (1.08–1.92)* |

| Lifetime substance use disorder before onset COVID-19 outbreak | 11.55 (6.18–21.56)* | 12.69 (6.17–26.11)* | n.a. | n.a. | 6.02 (3.21–11.28)* | 6.20 (2.91–13.19)* |

| Other lifetime mental disorder before onset COVID-19 outbreak | 1.62 (1.26–2.09)* | 2.32 (1.64–3.30)* | n.a. | n.a. | 0.79 (0.61–1.03) | 1.04 (0.72–1.50) |

| Any lifetime mental disorder before onset COVID-19 outbreak | 3.21 (2.93–3.51)* | 3.97 (3.40–4.63)* | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Having two or more lifetime mental disorders (vs. zero or exactly one) | 4.72 (3.95–5.65)* | 7.34 (5.85–9.21)* | n.a. | n.a. | 2.52 (2.09–3.05)* | 3.79 (2.98–4.84)* |

Note: OR, odds ratio; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; n.a., not applicable.

All analyses adjust for time of survey (weeks), hospital membership and all predictors shown in the rows.

Statistically significant (α = 0.05).

The category “positive COVID-19 test or medical COVID-19 diagnosis” excludes those having been hospitalized for COVID-19.

The category “other family, friends or others” excludes having a partner, children, or parents infected with COVID-19.

Table 3 presents multivariable analyses of the associations described above, adjusting by all individual characteristics, COVID-19 exposure factors, and healthcare center and week of interview. Being female, and between ages 18–29 and being 30–49 were significantly associated with any and with any disabling current mental disorder. Being a physician and a nurse was consistently associated with significantly lower odds of current mental disorders, while being an auxiliary nurse with previous mental disorders showed high (but not significant) ORs of current disabling mental disorders. Being a frontline healthcare worker was a very important risk factor of any current and any disabling disorder, as it was also having been in quarantine or isolated. The factors most strongly associated with current disabling mental disorders were previous substance use disorders, anxiety disorder and depression disorders. Having more than one previous disorder was no longer statistically significant in the multivariate analysis.

Table 3.

Multivariable associations between individual characteristics, COVID-19 exposure, and prior lifetime (LT) mental disorders with probable current mental disorders and current disabling mental disorders. Spanish healthcare workers, MINDCOVID study (N = 9138).

| ALL (n = 9138) |

No prior LT mental disorders (new onset) (n = 5367) |

Prior LT mental disorder (persistence/relapse) (n = 3771) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any current mental disorder (n = 4118) | Any current disabling mental disorder (n = 1278) | Any current mental disorder (n = 1818) | Any current disabling mental disorder (n = 485) | Any current mental disorder (n = 2300) | Any current disabling mental disorder (n = 793) | |

| aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | |

| Gender - female (vs. male) | 1.45 (1.29–1.63)* | 1.58 (1.27–1.96)* | 1.54 (1.31–1.81)* | 1.77 (1.27–2.46)* | 1.36 (1.13–1.63)* | 1.50 (1.12–2.01)* |

| Age | ||||||

| -18–29 years | 1.53 (1.28–1.82)* | 1.36 (1.02–1.82)* | 1.82 (1.43–2.32)* | 1.67 (1.07–2.61)* | 1.23 (0.95–1.59) | 1.17 (0.80–1.71) |

| -30–49 year | 1.46 (1.30–1.64)* | 1.34 (1.09–1.64)* | 1.49 (1.27–1.74)* | 1.39 (1.04–1.87)* | 1.42 (1.19–1.70)* | 1.30 (0.98–1.74) |

| -50 years or more | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Marital status – married (vs. single, divorced or legally separated, or widowed) | 1.05 (0.95–1.17) | 1.02 (0.85–1.23) | 1.09 (0.94–1.26) | 1.09 (0.84–1.42) | 1.01 (0.86–1.19) | 0.98 (0.77–1.26) |

| Having children in care | ||||||

| -Younger (<12 ys) children in care | 0.97 (0.85–1.11) | 1.01 (0.81–1.26) | 1.00 (0.84–1.20) | 1.03 (0.74–1.42) | 0.93 (0.76–1.13) | 0.99 (0.73–1.33) |

| -Children in care, but >12 ys | 0.96 (0.84–1.11) | 0.89 (0.70–1.13) | 0.95 (0.78–1.14) | 0.82 (0.57–1.16) | 0.99 (0.80–1.24) | 0.95 (0.68–1.32) |

| -No children in care | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Profession | ||||||

| -Physician | 0.45 (0.39–0.53)* | 0.34 (0.26–0.44)* | 0.45 (0.37–0.55)* | 0.30 (0.20–0.45)* | 0.45 (0.36–0.56)* | 0.36 (0.25–0.52)* |

| -Nurse | 0.77 (0.67–0.90)* | 0.73 (0.57–0.92)* | 0.82 (0.67–0.99)* | 0.69 (0.48–0.98)* | 0.70 (0.56–0.87)* | 0.73 (0.53–1.01) |

| -Auxiliary nurse | 1.12 (0.94–1.34) | 1.07 (0.80–1.42) | 1.11 (0.87–1.41) | 0.92 (0.60–1.40) | 1.13 (0.85–1.50) | 1.18 (0.79–1.78) |

| -Other profession involved in patient care | 0.67 (0.55–0.80)* | 0.54 (0.39–0.75)* | 0.59 (0.45–0.77)* | 0.50 (0.30–0.82)* | 0.75 (0.56–1.00) | 0.57 (0.36–0.92)* |

| -Other profession not involved in patient care | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Frequency of direct exposure to COVID-19 patients | ||||||

| -All of the time | 3.98 (3.27–4.85)* | 5.19 (3.61–7.46)* | 4.40 (3.31–5.85)* | 6.62 (3.70–11.85)* | 3.53 (2.66–4.68)* | 4.27 (2.70–6.76)* |

| -Most of the time | 3.10 (2.54–3.76)* | 4.53 (3.17–6.48)* | 3.15 (2.36–4.20)* | 5.00 (2.77–9.01)* | 3.08 (2.34–4.06)* | 4.26 (2.70–6.71)* |

| -Some of the time | 2.50 (2.08–3.01)* | 2.96 (2.07–4.23)* | 2.74 (2.09–3.60)* | 3.25 (1.82–5.82)* | 2.24 (1.73–2.90)* | 2.71 (1.74–4.20)* |

| -A little of the time | 1.55 (1.27–1.90)* | 1.93 (1.33–2.80)* | 1.60 (1.19–2.14)* | 2.06 (1.13–3.78)* | 1.53 (1.15–2.03)* | 1.81 (1.12–2.92)* |

| -None of the time | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| COVID-19 infection history | ||||||

| -Having been hospitalized for COVID-19 | 1.06 (0.69–1.64) | 1.42 (0.76–2.65) | 0.92 (0.50–1.71) | 1.48 (0.60–3.65) | 1.23 (0.64–2.39) | 1.38 (0.57–3.34) |

| -Positive COVID-19 test or medical COVID-19 diagnosisa | 0.82 (0.70–0.95)* | 0.76 (0.60–0.96)* | 0.77 (0.63–0.93)* | 0.69 (0.48–1.01) | 0.88 (0.70–1.11) | 0.83 (0.60–1.14) |

| -None of the above | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Having been isolated or quarantined because of COVID-19 | 1.36 (1.20–1.54)* | 1.60 (1.31–1.95)* | 1.34 (1.13–1.59)* | 1.64 (1.20–2.25)* | 1.41 (1.16–1.71)* | 1.60 (1.21–2.11)* |

| Lifetime mood disorder before onset COVID-19 outbreak | 2.53 (2.04–3.15)* | 3.23 (2.27–4.60)* | n.a. | n.a. | 2.91 (1.29–6.57)* | 4.46 (1.65–12.03)* |

| Lifetime anxiety disorder before onset COVID-19 outbreak | 2.82 (2.53–3.13)* | 3.03 (2.53–3.62)* | n.a. | n.a. | 3.36 (1.49–7.58)* | 4.30 (1.61–11.43)* |

| Lifetime substance use disorder before onset COVID-19 outbreak | 8.25 (4.22–16.11)* | 5.74 (2.53–13.03)* | n.a. | n.a. | 9.17 (3.67–22.92)* | 7.23 (2.60–20.08)* |

| Other lifetime mental disorder before onset COVID-19 outbreak | 1.53 (1.15–2.05)* | 2.06 (1.35–3.13)* | n.a. | n.a. | 1.77 (0.80–3.89) | 2.69 (1.07–6.76)* |

| Having two or more lifetime mental disorders (vs. zero or exactly one) | 0.93 (0.69–1.24) | 1.17 (0.76–1.79) | n.a. | n.a. | 0.78 (0.33–1.83) | 0.83 (0.29–2.36) |

| AUC | 0.73 | 0.77 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.73 |

OR, adjusted Odd Ratio; CI, 95% Confidence Interval; ref, reference category; AUC, Area under the curve. SE, Standard Error, n.a. not applicable.

Each column represents a separate regression model, each time adjusting for time of survey (weeks), hospital membership, and all.

Statistically significant (α = 0.05).

The category “positive COVID-19 test or medical COVID-19 diagnosis” excludes those having been hospitalized for COVID-19.

Discussion

Our results document a high prevalence of current mental disorders, with almost half of respondents screening positive on at least one of the five well-established screeners for common mental disorders. Most important, 1 in 7 met criteria for a current disabling mental disorder. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to consider both symptom screening and disability as indicator of adverse mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Such a combination is potentially more valid and useful for services planning purposes, than descriptive information on psychological symptoms.41, 42 We also found that prevalence of adverse mental health was significantly more frequent among healthcare workers with prior mental disorders. Finally, we found that being a female, having a high frequency of exposure to COVID-19 patients, and having quarantined or isolated are risk factors for both any current disorder and any disabling disorder.

Comparison with other studies

The prevalence estimates of MDD (28.1%) and GAD (22.5%) we found are within the range of meta-analytic reports of healthcare workers studied in predominantly Asian healthcare settings.6, 8, 9 PTSD prevalence (22.2%) is also similar to a recent meta-analysis (20.7%).5 Substance use disorder was present in 6.2% of our sample. Only a few studies have reported empirical estimates of this disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic and we were unable to find any specific data among healthcare workers. Our results suggest that this disorder has a considerably lower prevalence than found in the general adult populations of the US43 and France.44

To the best of our knowledge, no previous report has presented data on the prevalence of any mental disorder and any disabling mental disorder among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The prevalence in our study (i.e., 45.7% of the responding healthcare workers meet criteria for any of the five assessed disorders) is somewhat higher than the 40.9% of ≥1 adverse mental or behavioral health symptom in the adult US population.43 More importantly, 1 in 7 presented a current disabling mental disorder, pointing to the high interference of adverse mental health on, professional, domestic, personal, and social activities. Our results suggest that there are large mental healthcare needs to meet among healthcare professionals. There is need to closely monitor the extent to which these needs are adequately met.

An important finding of our study is the strong association of prior lifetime disorders with any current disabling mental disorder (with odds ratios ranging from 1.53 to 8.25). This result, which is consistent with our clinical experience during the first wave of the pandemic, strongly suggests that healthcare workers with such a history must be considered a group at especially high risk. Adequate mental health monitoring and support measures should be made accessible and uptake of treatment use in this high-risk group should be a focus of further research.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of our study include the large number of participating institutions from the most affected regions of Spain; the use of institutional mailing lists as the a reliable sampling framework; data representative for a large number of healthcare workers; and including the criterion of severe interference to identify disabling mental disorders. These strengths support the robustness and relevance of our results.

Nevertheless, the study has some limitations that deserve careful consideration. First, we had a low response rate. Despite important advantages of institutional email lists, these email accounts appear not to be checked by a large majority of employees (<27%) and their utilization might differ by professional category. In addition, invitations reminders were limited to a maximum of 2 due to institutional requirements. It is possible that healthcare workers with mental health problems were more likely to participate. But it is also likely that the most stressed workers did not have time to respond. In order to improve representativeness, we have carefully weighted the observed data as to exactly reproduce the gender, age and professional category distribution of healthcare personnel in each participating institution.

Second, the study was cross-sectional in nature, precluding the inference of any causal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare workers. Nevertheless, we used clear and relevant recall periods to make sure the symptoms were present after the onset of the pandemic and we collected information on pre-pandemic lifetime mental disorders.

Third, measures used to assess mental disorders in our study are based on self-reports and not on clinical diagnoses. Nevertheless, there is good evidence of acceptable sensitivity and specificity of the assessment for the current score cutoffs used here for current major depression disorder,45 generalized anxiety disorder18 and post-traumatic stress disorders.23 These measures are among the most frequently used in epidemiologic studies which allows comparability of results. For lifetime disorders we used a list of disorders which have been shown to have acceptable agreement with clinical evaluations.46 The high prevalence of both lifetime and current mental disorders found in our study suggests that a part might include false positive cases; and some of the real cases may have a mild disorder. It is for this reason that we: (a) use the term “probable” disorder to refer to workers screening positive using the recommended cut-off scores for screening; and (b) consider disabling current mental disorders to be a better estimate of the needs for mental healthcare in this population, since it includes functional limitation, according to DSM-5 indications.41, 42 Healthcare workers with disabling current mental disorder in our study had much more frequent (between 2 and three times more) mental comorbidity, current suicidal ideation, poor perceived (data not presented, available upon request).

Finally, we have not studied here the use of services for mental disorders, a really important complement to the issue of need for care. This issue requires specific analyses that we plan to address in the immediate future.

Conclusions

Notwithstanding these limitations, our study shows a high prevalence of probable current mental disorders among Spanish healthcare workers during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, with 1 in 7 presenting a disabling mental disorder. Prevalence of adverse mental health was significantly more frequent among healthcare workers reporting lifetime mental disorders before the pandemic, which identifies a group in need of current monitoring and adequate support, especially as the pandemic is entering in successive waves. Other healthcare workers that should be monitored include with a high frequency of exposure to COVID-19 patients, who had been infected or have been quarantined or isolated, as well as female workers, and auxiliary nurses.

Transparency statement

The lead author (JA) states that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being presented, that no important aspect of the study has been omitted, and that differences from the study that was initially planned have been explained (and if relevant, recorded).

Contributors

JA, GV, and PM reviewed the literature. JA, GV, PM, MF, EA, VPS, JMH, RCK, and RB conceived and designed the study. EA, JDM, NL, TP, JMPT, JIP, JIE, ME, NP, AGP, CR, EA, ICG, AAP, MC, APZ, EV, CS, and VPS acquired the data. GV, IA, and PM cleaned and analyzed the data. JA, GV, and PM drafted the initial version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the initial draft and made critical contribution to the interpretation of the data and approved the manuscript. The corresponding authors attest that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding

This work was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación)/FEDER (COV20/00711); ISCIII (Sara Borrell, CD18/00049) (PM); FPU (FPU15/05728)); ISCIII (PFIS, FI18/00012); Generalitat de Catalunya (2017SGR452).

Conflict of interest statement

EV reports personal fees from Abbott, personal fees from Allergan, personal fees from Angelini, grants from Novartis, grants from Ferrer, grants and personal fees from Janssen, personal fees from Lundbeck, personal fees from Sage, personal fees from Sanofi, outside the submitted work. JDM reports personal fees from Janssen, personal fees and non-financial support from Otsuka, personal fees and non-financial support from Lundbeck, personal fees from Angelini, personal fees and non-financial support from Accord, outside the submitted work. In the past 3 years, RCK was a consultant for Datastat, Inc, Sage Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda. All other authors reported no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank all healthcare workers that participated in the study in extremely busy times. They also thank very much Puri Barbas and Franco Amigo for the management of the project, and Carme Gasull for manuscript preparation and submission.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2020.12.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Holmes E.A., O’Connor R.C., Perry V.H., Tracey I., Wessely S., Arseneault L., et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vindegaard N., Benros M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen L.H., Drew A.D., Graham M.S., Joshi A.D., Guo C.G., Ma W., et al. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;5:e475–e483. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30164-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC COVID-19 Response Team Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19: United States, February 12–April 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:477–481. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazzerini M., Putoto G. COVID-19 in Italy: momentous decisions and many uncertainties. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e641–e642. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30110-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo M., Guo L., Yu M., Jiang W., Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public – a systematic review and metaanalysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113190. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salázar de Pablo G., Vaquerizo-Serrano J., Catalán A., Arango C., Moreno C., Ferre F., et al. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pappa S., Ntella V., Giannakas T., Giannakoulis V.C., Papoutsi E., Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.García-Iglesias J.J., Gómez-Salgado J., Martín-Pereira J., Fagundo-Rivera J., Ayuso-Murillo D., Martínez-Riera J.R., et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) on the mental health of healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2020;94:e202007088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García-Fernández L., Romero-Ferreiro V., López-Roldán P.D., Padilla S., Calero-Sierra I., Monzo-García M., et al. Mental health impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Spanish healthcare workers. Psychol Med. 2020;27 doi: 10.1017/S0033291720002019. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dosil-Santamaria M., Ozamiz-Etxebarria N., Redondo-Rodríguez I., Jaureguizar-Alboniga-MayorJ, Picaza-Gorrotxategi M. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on a sample of Spanish Health professionals. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2020.05.004. June 2 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luceño-Moreno L., Talavera-Velasco B., Garcia-Albuerne Y., Martín-García J. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression, levels of resilience and burnout in spanish health personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:5514. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruiz-Fernández M.D., Ramos-Pichardo J.D., Ibáñez-Masero O., Cabrera-Troya J., Carmona-Rega M.I., Ortega-Galan A.M. Compassion fatigue, burnout, compassion satisfaction and perceived stress in healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 health crisis in Spain. J Clin Nurs. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jocn.15469. August 28 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salas-Nicas S., Sembajwe G., Navarro A., Moncada S., Llorens C., Buxton O.M. Job insecurity, economic hardship, and sleep problems in a national sample of salaried workers in Spain. Sleep Health. 2020;6:262–359. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2020.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodríguez-Menéndez G., Rubio-García A., Conde-Alvarez P., Armesto-Luque L., Garrido-Torres N., Capitan L., et al. Short-term emotional impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Spaniard Health workers. J Affect Dis. 2021;278:390–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Díez-Quevedo C., Rangil T., Sánchez-Planell L., Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L. Validation and utility of the patient health questionnaire in diagnosing mental disorders in 1003 general hospital Spanish inpatients. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:679–686. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Y., Levis B., Riehm K.E., Saadat N., Levis A.W., Azar M., et al. Equivalency of the diagnostic accuracy of the PHQ-8 and PHQ-9: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2020;50:1368–1380. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman M.G., Zuellig A.R., Kachin K.E., Constantino M.J., Przeworski A., Erickson T., et al. Preliminary reliability and validity of the generalized anxiety disorder questionnaire-IV: a revised self-report diagnostic measure of generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Ther. 2002;33:215–233. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(02)80026-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.García-Campayo J., Zamorano E., Ruiz M.A., Pardo A., Pérez-Páramo M., López-Gómez V., et al. Cultural adaptation into Spanish of the generalized anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale as a screening tool. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler R.C., Santiago P.N., Colpe L.J., Dempsey C.L., First M.B., Heeringa S.G., et al. Clinical reappraisal of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Screening Scales (CIDI-SC) in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2013;22:303–321. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blasco M.J., Castellví P., Almenara J., Lagares C., Roca M., Sesé A., et al. Predictive models for suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Spanish University students: rationale and methods of the UNIVERSAL (University & mental health) project. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:122. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0820-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weathers F.W., Litz B.T., Keane T.M., Palmieri P.A., Marx B.P., Schnurr P.P. Department of Veterans Affairs; U.S: 2013. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) https://www.ptsd.va.gov [accessed 20.05.20] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuromski K.L., Ustun B., Hwang I., Keane T.M., Marx B.P., Stein M.B., et al. Developing an optimal short-form of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) Depress Anxiety. 2019;36:790–800. doi: 10.1002/da.22942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Resick P., Chard K., Monson C. 2020. Cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) https://cptforptsd.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/PCL-5-Spanish-version.pdf [accessed 28.09.20] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hinkin C.H., Castellon S.A., Dickson-Fuhrman E., Daum G., Jaffe J., Jarvik L. Screening for drug and alcohol abuse among older adults using a modified version of the CAGE. Am J Addict. 2001;10:319–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2001.tb00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Díez-Martínez S., Martín-Moros J.M., Altisent-Trota R., Aznar-Tejero P., Cebrián-Martín C., Imáz- Pérez F.J., et al. Brief questionnaires for the early detection of alcoholism in primary health care. Aten Primaria. 1991;8:367–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saitz R., Lepore M.F., Sullivan L.M., Amaro H., Samet J.H. Alcohol abuse and dependence in Latinos living in the United States. Validation of the CAGE (4M) questions. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:718–724. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.7.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López-Maya L., Lina-Manjarrez F., Navarro-Henze S., López L.M.L. Adicciones en anestesiólogos. ¿Por qué se han incrementado? ¿Debemos preocuparnos? Rev Mex Anestesiol. 2012;35:95–106. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mdege N.D., Lang J. Screening instruments for detecting illicit drug use/abuse that could be useful in general hospital wards: a systematic review. Addict Behav. 2011;36:1111–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leon A.C., Olfson M., Portera L., Farber L., Sheehan D.V. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27:93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ormel J., Petukhova M., Chatterji S., Aguilar-Gaxiola S., Alonso J., Angermeyer M.C., et al. Disability and treatment of specific mental and physical disorders across the world. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:368–375. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luciano J.V., Bertsch J., Salvador-Carulla L., Tomás J.M., Fernández F., Pinto-Meza A., et al. Factor structure, internal consistency and construct validity of the Sheehan Disability Scale in a Spanish primary care samplej ep_1211 895.901. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16:895–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessler R.C., Ustün T.B. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wittchen H.U., Nelson C.B., Lachner G. Prevalence of mental disorders and psychosocial impairments in adolescents and young adults. Psychol Med. 1998;28:109–126. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alonso J., Vilagut G., Mortier P., Auerbach R.P., Bruffaerts R., Cuijpers P., et al. The role impairment associated with mental disorder risk profiles in the WHO World Mental Health International College Student Initiative. Int J Methods Psychol Res. 2019;28:e1750. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benjamini Y., Drai D., Elmer G., Kafkafi N., Golani I. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Beh Brain Res. 2001;125:279–284. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Buuren S., Groothuis- Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Buuren S. Second Edition. Chapman and Hall/CRC Press; Boca Raton, Florida: 2018. Flexible imputation of missing data. [Google Scholar]

- 39.R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2017. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [https://www.r-project.org/] https://www.r-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 40.SAS Institute Inc. SAS Inst. Inc. Mark. Co; 2014. SAS Software 9.4. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alonso J., Codony M., Kovess V., Angermeyer M.C., Katz S.J., Haro J.M., et al. Population level of unmet need for mental healthcare in Europe. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:299–306. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.022004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Narrow W.E., Rae D.S., Robins L.N., Regier D.A. Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the United States: using a clinical significance criterion to reconcile 2 surveys’ estimates. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:115–123. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Czeisler M.E., Lane R.I., Petrosky E., Wiley J.F., Christensen A., Njai R., et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic – United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rolland B., Haesebaert F., Zante E., Benyamina A., Haesebaert J., Franck N. Global changes and factors of increase in caloric/salty food intake, screen use, and substance use during the early COVID-19 containment phase in the general population in France: survey study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:e19630. doi: 10.2196/19630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sánchez-Villegas A., Schlatter J., Ortuno F., Lahortiga F., Pla J., Benito S., et al. Validity of a self-reported diagnosis of depression among participants in a cohort study using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I) BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-43. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/8/43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.