Abstract

During amyloidogenesis, proteins undergo conformational changes that allow them to aggregate and assemble into insoluble, fibrillar structures. Soluble oligomers that form during this process typically contain 2–24 monomeric subunits and are cytotoxic. Before the formation of these soluble oligomers, monomeric species first adopt aggregation-competent conformations. Knowledge of the structures of these intermediate states is invaluable to the development of molecular strategies to arrest pathological amyloid aggregation. However, the highly dynamic and interconverting nature of amyloidogenic species limits biophysical characterization of their structures during amyloidogenesis. Here, we use molecular dynamics simulations to probe conformations sampled by monomeric transthyretin under amyloidogenic conditions. We show that certain β-strands in transthyretin tend to unfold and sample nonnative conformations and that the edge strands in one β-sheet (the DAGH sheet) are particularly susceptible to conformational changes in the monomeric state. We also find that changes in the tertiary structure of transthyretin can be associated with disruptions to the secondary structure. We evaluated the conformations produced by molecular dynamics by calculating how well molecular-dynamics-derived structures reproduced NMR-derived interatomic distances. Finally, we leverage our computational results to produce experimentally testable hypotheses that may aid experimental explorations of pathological conformations of transthyretin.

Significance

The conformations of amyloid proteins have been investigated using diverse experimental techniques. Over six decades of work have yielded several structures of amyloid fibrils, but the structures of toxic conformations formed before the fibrils are much less characterized. Knowledge of these conformations is necessary to develop technologies that mitigate the biomedical burden of amyloid. To this end, we used molecular dynamics to simulate early structural changes in transthyretin monomers. These simulations track the behavior of single molecules and provide atomic-level details into the molecular mechanisms that drive protein misfolding. We use these simulations to propose early conformational changes during amyloid formation, interpret sparse experimental data, and generate hypotheses for future experiments.

Introduction

During amyloidogenesis, proteins self-aggregate into insoluble fibrils (1,2). During this “reaction,” aggregating proteins sample a heterogeneous ensemble of conformations, including nativelike monomers, aggregation-competent monomers, soluble oligomers, protofibrils, mature fibrils, and amyloid plaques. In total, 36 proteins from Homo sapiens and 10 from other animals have been associated with the formation of pathological amyloid fibrils (3). Despite the ubiquity of amyloid, a clear understanding of the conformations that are sampled en route to fibril formation remain elusive. Increasing evidence frames the intermediate conformers—namely, the soluble oligomers—as the agents responsible for amyloid pathologies (4, 5, 6, 7). Improved models of these intermediate conformers as well as a delineation of the pathways that connect native and fibrillar species are urgently needed to engineer therapeutic and diagnostic strategies that can diagnose, treat, or prevent amyloidosis.

The biophysical characterization of amyloid proteins is not trivial. Disordered, heterogeneous, and transient conformations are challenging to isolate and stabilize under conditions suitable for x-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy. Furthermore, amyloidogenesis occurs across a range of timescales: aggregation can take up to weeks in vitro, yet conformational changes occur on the submicrosecond timescale. Experimental studies on amyloid proteins can track the extent of aggregation as a function of time (8,9), monitor how various environments (e.g., pH, temperature, protein concentration, or small molecules) modulate aggregation kinetics (9, 10, 11), or quantify the structural properties (usually at low resolution) of amyloid species (5,12,13). Computational studies of the structure and dynamics of amyloid proteins have studied the loss of native structure during amyloidogenesis (14, 15, 16, 17, 18), effects of mutations on the structure of amyloid proteins (19, 20, 21, 22), the formation and conformations of dimers and oligomers (23,24), how the properties of a solution (e.g., pH, cosolvents) affect the structure of amyloid proteins (25, 26, 27, 28), and the interactions between small molecules and amyloid proteins (29,30). Iteration between computational and experimental techniques can be an effective strategy to map the amyloid landscape.

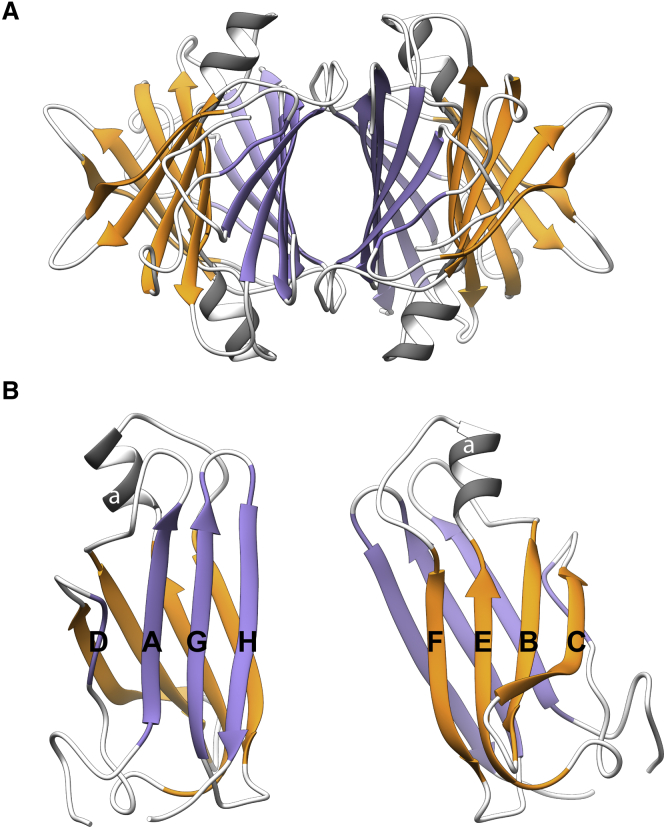

Transthyretin (TTR, a transporter of thyroxine and retinol) is an amyloidogenic protein that has been extensively studied. TTR has several properties that distinguish it from other amyloid proteins. Its native structure is known and well defined: TTR is a homotetrameric, 55-kDa protein comprising four 127-residue monomers that each form a β-sandwich fold with two sheets: the DAGH and CBEF sheets (Fig. 1). TTR aggregation proceeds from a nativelike monomeric species, and a high degree of nativelike structure is hypothesized to be present in oligomeric and fibrillar forms of TTR. The results of many experimental studies provide diverse insights into amyloid formation by TTR and can be used to assess computational findings.

Figure 1.

The crystallographic conformation of transthyretin. The crystallographic structures (PDB: 1TTA) of a wild-type TTR tetramer (A) and monomer (B) are shown. The DAGH sheet is colored purple, the CBEF sheet is colored orange, the α-helix is dark gray, and loops are light gray. To see this figure in color, go online.

The current model of oligomeric conformations of TTR is shaped by results from x-ray crystallography, NMR, computation, and protein design. Early clinical reports identified genetic variants associated with amyloid pathologies and showed that a large number of mutations fall in the CBEF sheet of TTR, particularly in the edge strands. It was thought that mutation-induced structural changes to this sheet initiated aggregation. However, an analysis of 23 crystal structures showed that the small amplitude changes to the tertiary structure of TTR were not able to yield significant insights into amyloidogenesis (31). Currently, there are nearly 300 crystal structures of TTR from H. sapiens deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB, www.rcsb.org), the majority of which have near-identical backbone conformations (32). One structure with a large Cα RMSD relative to the 1TTA structure (PDB: 1G1O) is a designed triple mutant (G53S, E54D, L55S) that is highly amyloidogenic; however, the major differences in the crystal structure are a shift in the registry of strand D and a rearrangement of the DE loop (33).

Various biophysical techniques have been employed to study amyloid formation by transthyretin. Hydrogen-deuterium exchange was used to probe the solvent accessibility of TTR under amyloidogenic conditions and identify significant conformational changes during amyloidogenesis. The hydrogen-deuterium exchange results indicated that strands C and D unfold during amyloidogenesis and that destabilization of the CBEF sheet initiates aggregation (34). Solid-state NMR and relaxation-dispersion experiments of WT and monomeric TTR (F87M/L110M) have predicted that the initial conformational changes to TTR monomers occur in the DAGH sheet (35). Various studies have predicted that destabilization of either the CBEF sheet or the DAGH sheet initiates aggregation, whereas others indicate that nativelike DAGH and CBEF structures are present during aggregation (34,36, 37, 38). Thus, the conformational changes that occur during amyloid formation have yet to be definitively established and may be subject to modification by many variables.

Computational techniques have also been employed to investigate amyloid formation by TTR. In prior molecular dynamics studies from our group, we have shown that the DAGH sheet of both WT and mutant TTR monomers undergoes a conversion from β-sheet to α-sheet secondary structure (16,17,22,39). Molecular dynamics (MD) studies from other groups have also observed α-sheet conversion in the DAGH sheet (40), destabilization of hydrogen bonding patterns in the CBEF sheet (41), and a disruption of hydrogen bonding in the DAGH sheet (42).

Protein redesign has also been used to map amyloid formation by transthyretin. Three sets of TTR designs have been developed to investigate its amyloid formation. The first contains three mutations within strand D (G53S, E54D, and L55S); these mutations result in a highly amyloidogenic variant with altered native structure in strand D (33). The second contains two mutations (F87M and L110M, also known as monomeric TTR) that result in a TTR variant that is natively monomeric and does aggregate unless partially denatured (43). The last set of designs contains various mutations to H88 (H88A, H88F, H88S, and H88Y) (44). These mutations were introduced to probe the role that H88 plays in TTR amyloid formation. The four His designs showed that mutation at this position modulates the degree of amyloidogenicity of TTR (44).

Some insights into TTR amyloidogenesis contain contradictory predictions regarding the structure of TTR during the early stages of aggregation. The most apparent contradiction is whether the CBEF sheet or DAGH sheet is more destabilized and how different conditions affect the stability of the sheets. Several confounding factors likely contribute to this uncertainty. To address this issue, we used conventional MD simulations to probe early conformational changes that occur to wild-type (WT) and mutant TTR monomers, focusing on nonnative monomers as potential models of building blocks for aggregation, but not oligomeric or fibrillar forms of TTR. In a prior study, analysis of this same set of simulations was used to map out changes to the secondary structure of transthyretin (39). Here, we characterize tertiary changes to the structures in our simulations, compare the conformational landscape observed in MD with experimental data, and generate testable hypotheses that we speculate may be used to aid in the identification of the conformation(s) of aggregation-competent TTR monomers in future experiments.

Methods

Model building

The coordinates of the 1.7-Å crystal structure of WT TTR (PDB: 1TTA) were obtained from the PDB (45). The 1TTA crystal structure was chosen because it contains coordinates for the full-length protein and did not require modeling of the unstructured N- and C-termini. When duplicate side chains were present, the first rotameric state was chosen (conformer A; this affected residues C10, M13, L17, K48, E63, D74, K80, L82, R104, and T119). Models of the six mutant forms of TTR (D18G, A36P, L58H, Y69H, L111M, and V122I) were generated via in silico mutations of the WT structure (chain A of the 1TTA x-ray structure) using the Dynameomics rotamer library (46,47). As previously noted, mutations to TTR rarely result in a significant deviation from the crystal structure present in 1TTA (48). Each of the seven TTR variants was modeled under the most common in vitro model of amyloidogenic conditions: acidic pH (∼4.4) via protonation of Asp (named Ash, net charge of 0), Glu (named Glh, net charge of 0), and His (named Hip, net charge of +1) residues. In experimental studies, TTR has maximal aggregation at pH 4.4. This acidic pH roughly corresponds to that of a lysosome, in which aggregation is hypothesized to begin in vivo (49,50). In silico pKa algorithms predict that most titratable residues in chain A of 1TTA would be protonated at pH 4.4; E7, D18, D38, D39, E54, E61, E72, D74, E92, D99, and E127 are not predicted to be protonated (51). However, those algorithms have limited accuracy because they employ implicit solvent models, do not account for conformational flexibility, and do not account for coupling between protonation and conformation. Classical MD simulations are similarly limited in that the protonation states of ionizable residues cannot change during the simulation. In the absence of rigorous experimental data, there is no obvious choice for a protonation scheme. We therefore modeled a scenario in which all Asp, Glu, and His residues are protonated.

Molecular dynamics simulations

The starting structures described previously were prepared for MD simulations using the in lucem molecular mechanics (ilmm) package (52,53), which has been validated against a set of >3100 experimental observables (54). First, missing hydrogen atoms were modeled on the crystal structure and then minimized for 500 steps. This structure was used as the crystallographic “reference state” during analysis. Next, all atoms were minimized via steepest descent minimization for 1000 steps. Next, the proteins were solvated in a water box that extended at least 10 Å beyond any protein atom, and the box volume was adjusted to reproduce the experimental density at 310 K (0.992 g/mL) (55). Solvent atoms were minimized for 1000 steps, equilibrated for 500 steps, and then minimized again for 500 steps. Finally, all protein atoms were minimized for 500 additional steps. Production MD simulations were performed using ilmm with the Levitt et al. force field (56) and the flexible three-center (57) water model. Simulations were performed using the microcanonical NVE (constant number of particles, volume, and energy) ensemble with periodic boundary conditions, a 10-Å force-shifted nonbonded cutoff (58), and a 2-fs time step. Coordinates were saved every picosecond for analysis. All (n = 21) production simulations were performed at 310 K, acidic pH, and in triplicate for 500 ns for an aggregate simulation time of 10.5 μs. The set of simulations discussed here is the same set that was previously used for our analysis of secondary structure conversion in TTR (39). Here, we expand on our investigation of these simulations to investigate conformational changes that alter the globular structure of TTR monomers before oligomer formation.

Molecular dynamics analysis

Unless specified otherwise, analyses were performed using ilmm, the first 25-ns period of each simulation was excluded when reporting average values, and simulations were sampled at 1 ps granularity.

RMSD calculations

The Cα root mean-square deviation (RMSD) for each simulation as a function of time was calculated using ilmm. Residues in strands A (11–18), B (28–36), E (65–74), and G (104–112) were used for trajectory alignment, and the Cα RMSD was calculated for residues 11–123 (flexible N- and C-terminal residues were excluded). The Cα RMSD of individual edge strands was calculated after alignment to the interior strands in the same sheet. The Cα RMSDs for strands D (residues 53–56) and H (115–123) were calculated after aligning strands A (residues 11–18) and G (104–112) of the MD-derived structures to strands A and G in the minimized x-ray structure. Similarly, the Cα RMSDs for strands C (residues 40–48) and F (residues 90–97) were calculated after a structural alignment on strands B (residues 28–36) and E (residues 65–74).

Pairwise RMSD matrix generation

The Cα RMSD matrix was constructed via alignment of all simulations to residues within the strands (A: 11–18, B: 28–36, C: 40–48, D: 53–56, E: 65–74, F: 90–97, G: 104–112, H: 115–123), and the Cα RMSD was calculated for only those residues. Simulations were sampled at 1-ns granularity for construction of the RMSD matrix.

Multidimensional scaling

Multidimensional scaling (MDS) was performed using the SMACOF (59) algorithm as implemented in sklearn (60).

Contact analysis

Intramolecular protein hydrogen bonds were identified when the distance between the donor-acceptor pair was less than 2.6 Å and no greater than 45° from linearity. Hydrophobic contacts were detected if two C atoms from separate residues were within 5.4 Å of one another. For the side-chain-to-side-chain network analysis, two side chains were considered in contact with one another if they formed a hydrogen bond or at least one pair of heavy atoms from the two side chains were within 5.4 Å (carbon-carbon atom pairs) or 4.6 Å (all other atom pairs) of one another.

Evaluation of interatomic distances derived from solid-state NMR

Solid-state NMR experiments performed on mature TTR amyloid fibrils have yielded interatomic distances present in mature fibrils. We calculated these interatomic distances from our simulations. In contrast to solution-state NMR, solid-state NMR signals are proportional to inverse cubed distances. Interatomic distances between the C and Cα atoms of residue pairs were measured as a function of time. Average distances between atoms i and j (davgi, j) were calculated on a per-simulation basis according to Eq. 1.

| (1) |

Figure preparation

Protein images were prepared with UCSF Chimera (61). The remaining figures were prepared with matplotlib (62).

Ensemble averaging

Some results described here are the result of an ensemble average across all TTR systems that have been simulated. This ensemble average was done to highlight those structural changes that were common to the various TTR constructs that were simulated, as there were few conformational changes that were significantly correlated with a specific mutation. Specific results for individual simulations are provided in the Supporting Material and are discussed separately in the main text when pertinent.

Results

Conformations sampled during MD

We performed a total of 21 simulations of WT and variant (D18G, A36P, L58H, Y69H, L111M, and V122I) TTR under amyloidogenic conditions (Fig. 1). Each system was simulated in triplicate for 500 ns, yielding a net sampling time of 10.5 μs.

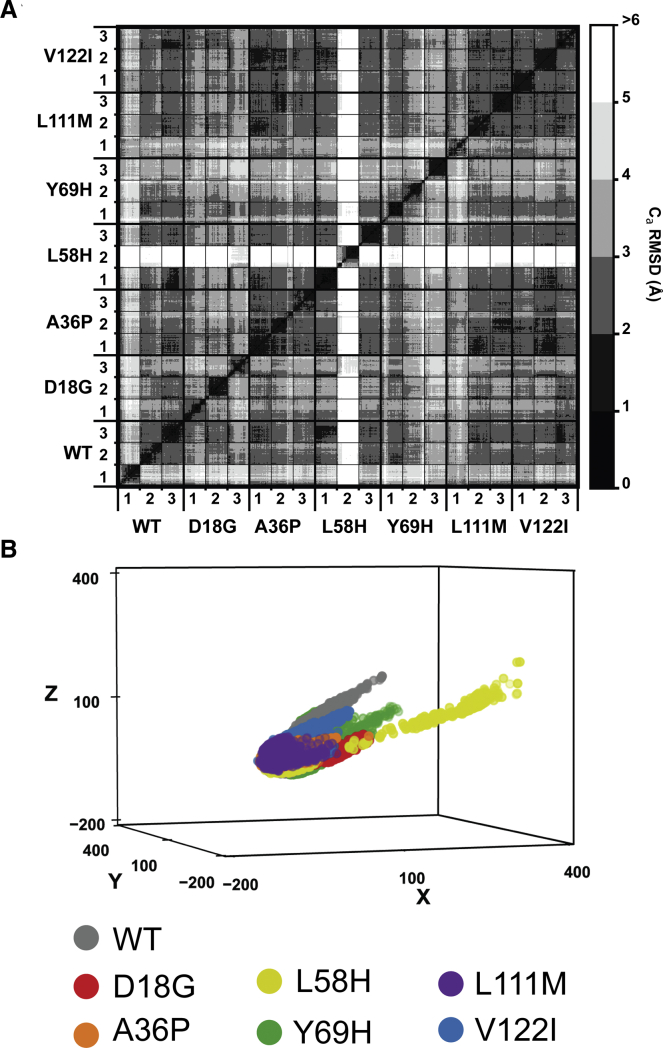

In a prior study (39), we showed that this degree of sampling was sufficient to observe changes to the secondary structure of TTR that are associated with amyloid formation. To quantify changes to the tertiary structure of TTR, we constructed a pairwise Cα RMSD matrix that included all simulations sampled every 1 ns (Fig. 2 A). Most simulations sampled conformations within 6 Å of the crystallographic conformer, and the average pairwise Cα RMSD among structures in this data set was 3.2 Å. Extensive conformational changes occurred in two simulations: TTRWT run 1 and TTRL58H run 2, which had average Cα RMSDs of 4.3 and 7.2 Å relative to the crystallographic conformer, respectively.

Figure 2.

Tertiary conformations sampled during MD. (A) The Cα RMSD matrix highlights conformational diversity of TTR monomers during MD simulations. The central diagonal line is a comparison of each structure in the data set to itself and is always 0 Å. Submatrices along the diagonal that are surrounded by thin black lines are a comparison of each structure in a simulation to all other structures in that same simulation. Submatrices along the diagonal that are surrounded by thick black lines are a comparison of each structure in a system (WT or mutant TTR) to all other structures in that same system. Off-diagonal elements are comparisons between different systems. Large off-diagonal RMSD values (white) are indicative of unique conformations not observed in other simulations, e.g., L58H. Small off-diagonal RMSD values (black) indicate that a conformation is sampled in multiple systems or simulations. (B) A three-dimensional projection of the pairwise Cα RMSD data set after application of the MDS algorithm. Points are plotted in a dimensionless, embedded-coordinate space and colored on a per-system basis (WT: gray, D18G: red, A36P: orange, L58H: yellow, Y69H: green, L111M: purple, V122I: blue). To see this figure in color, go online.

In TTRWT run 1, strand H dissociated from the DAGH sheet and formed contacts with strand F; in TTRL58H run 2, strands C and D unfolded and became disordered. Although the extent of sampling achieved was not exhaustive, several conformational changes that occurred in multiple simulations are suggestive of common conformational rearrangements that occur during the formation of aggregation-competent forms of TTR.

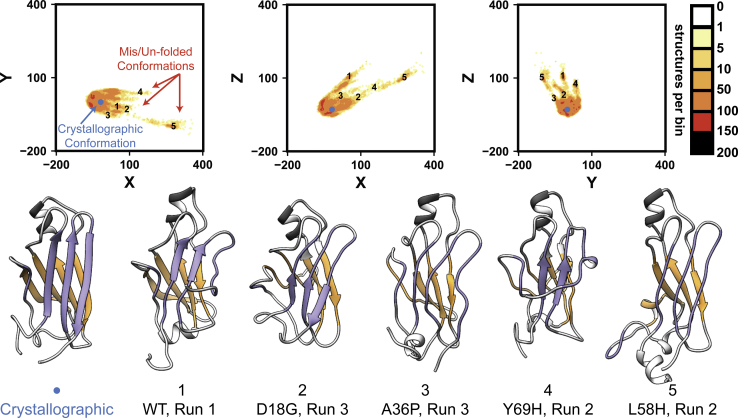

To identify the largest-amplitude conformational changes that occurred in our simulations, an MDS algorithm (63) was used to reduce the dimensionality of the pairwise Cα RMSD matrix from 10,500 to 3. The MDS algorithm embeds conformational dissimilarity data from the 10,500-dimensional Cα RMSD matrix into 3 abstract dimensions while preserving the relative distances between samples to the greatest extent possible (Fig. 2 B). MDS has been extensively used to map conformational changes in other systems (64) and to identify intermediate states populated during unfolding (65, 66, 67). Here, MDS was employed to identify early events in the conversion of TTR from the crystallographic structure to nonnative conformations, some of which may be aggregation competent. The embedded pairwise Cα RMSD data showed that most simulations sampled structures similar to the crystallographic conformer, although some other more pronounced excursions from the native state were identified. Visual analysis of these excursions showed that the most significant conformational changes involved rearrangements and (partial) dissociation of the edge strands in TTR: strands C, D, F, and H (Figs. 3, S1, and S2).

Figure 3.

Multidimensional scaling highlights excursions from the native TTR conformation. Each plot shows a two-dimensional histogram of the pairwise Cα RMSD data set after application of the MDS algorithm. Values are plotted in a dimensionless, embedded-coordinate space and colored based on the extent of sampling observed. The blue circle represents the position of the crystallographic reference structure. The annotated points (1–5) correspond to the mis/unfolded conformations shown at the bottom of the figure. To see this figure in color, go online.

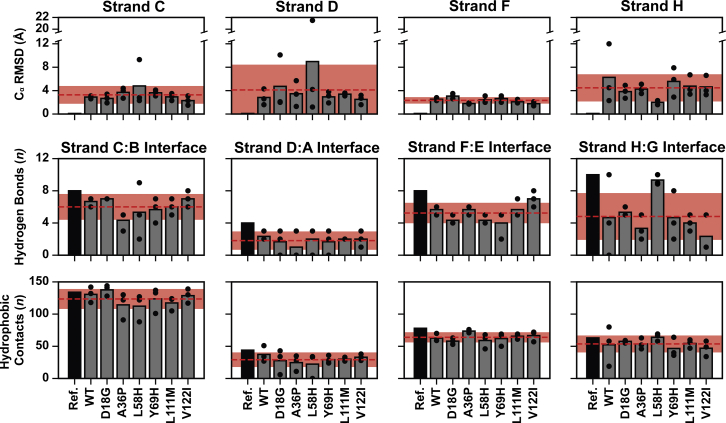

Edge strand dissociation in transthyretin

The conformational heterogeneity of the edge strands (C, D, F, and H) was determined by calculating the strand Cα RMSD relative to the crystallographic conformation as well as the number of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions that were retained relative to the crystallographic strand interfaces: i.e., the CB (residues 28–36, 40–49), DA (residues 11–18, 53–56), EF (residues 66–74, 90–97), and GH (residues 104–112, 115–123) interfaces. Strands H and D were the least nativelike, strand C lost nativelike structure at the ends of the strands, and strand F was the most nativelike (Fig. 4). We averaged these results over the final 25 ns of the simulation. Calculation of results over this subset of the simulation highlights the extent of conformational changes that occurred but does not capture simulation-to-simulation variabilities in the rates of strand dissociation. The dynamics of strand dissociation were analyzed in more detail for four simulations that showed dissociation or partial dissociation of strands H (TTRWT run 1), D (TTRD18G run 3), C (TTRA36P run 3), and F (TTRY69H run 2). The more common dissociation events, associated with strands H and D, are discussed below; the comparatively rarer dissociations for strands C and F are discussed in detail in the Supporting Materials and Methods and Figs. S3 and S4. In the TTRL58H run 2 simulation, strands C and D both dissociated from their respective β-sheets and sampled disordered conformations. The dynamics associated with the dissociation of strands C and D described here were both observed in TTRL58H run 2 (Fig. S5).

Figure 4.

Loss of interfacial interactions and dissociation of the edge strands. We evaluated the conformations sampled by the edge strands (C, D, F, and H) by quantifying their structural similarity to the native conformation and the number of interactions formed at strand interface. (top row) The Cα RMSDs of the edge strands quantify the structural similarity of the edge strands to their native conformations. Cα RMSD values were calculated after alignment to the central strands in the same sheet. Structures from MD trajectories were aligned to the minimized structure on the Cα atoms of either strands A and G (for calculations of strands D and H RMSD) or strands B and E (for calculations of strands C and F RMSD). The average number of hydrogen bonds (middle row) and the average number of hydrophobic contacts (bottom row) formed between each edge strand and its interfacial partner quantify changes in interactions made by the edge strands. The reported values were averaged over the final 25 ns of each simulation. In all of the charts, the black bars correspond to the value present in the crystallographic reference structure, each gray bar corresponds to the average value among the three replicate simulations for a given system, and each black circle corresponds to the value obtained from a single simulation. The dashed red lines and shaded red regions correspond to the mean and standard deviation across all MD simulations. To see this figure in color, go online.

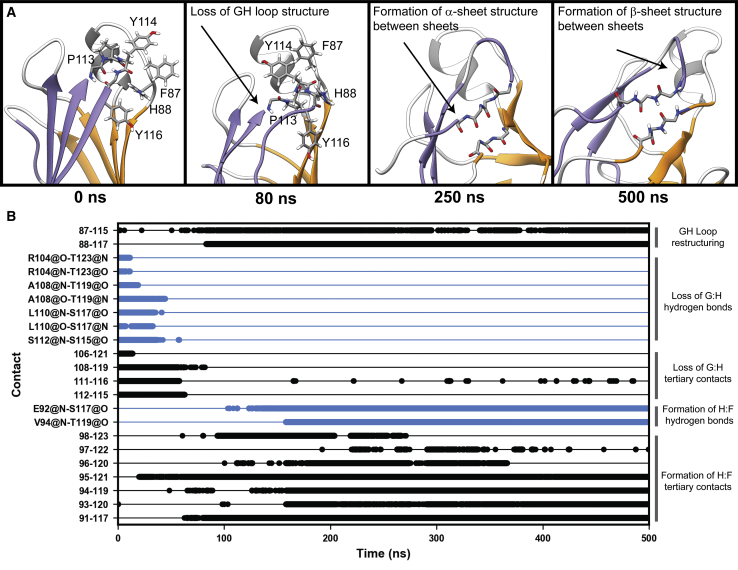

Dissociation of strand H

Dissociation of strand H was the most common structural change that occurred among TTR monomers in this data set (Fig. 4). The dynamics of H-strand dissociation are illustrated here using run 1 of the TTRWT as an example. Dissociation initiated at both the N- and C-terminal ends of strand H. At the N-terminal end, dissociation began with the displacement of the GH loop from its native structure. In the crystallographic conformation, P113 in the GH loop forms a main-chain-to-main-chain hydrogen bond with F87 in the EF loop, and four aromatic residues (F87, H88, Y114, and Y116) are well packed around the GH loop. After ∼10 ns of sampling in MD, this main-chain-to-main-chain hydrogen bond was lost, packing interactions among the four aromatic residues were lost, and the GH loop projected toward solvent. Displacement of the GH loop occurred in all MD simulations in this study. At the C-terminus, residues in strand H progressively lost main-chain-to-main-chain hydrogen bonds with strand G. Loss of these hydrogen bonds resulted in near-complete solvation of these residues. At 63 ns, there was a loss of hairpin structure in the GH loop that facilitated nonnative interactions between residues in strand H and residues in the EF loop and strand F. Beginning at 135 ns, the number of interactions between strands H and F increased: residues 117 and 119 formed hydrogen bonds with residues 92 and 94. Although strand H dissociated in other simulations, the WT run 1 simulation was the only instance in which we observed the formation of secondary structure elements between strands H and F. Instead, the dissociated strand H preferentially sampled disordered conformations in solvent (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Dynamics of strand dissociation at the G:H interface. (A) Snapshots from the simulation illustrate the sequence of events associated with the dissociation of strand H. At 0 ns, the GH loop and helix-EF loop are packed through interactions among several aromatic residues. Between 80 and 250 ns, nativelike structure in this region was lost: the GH loop lost hairpin structure and began to form interactions with strand F. By the end of the simulation, strand H formed main-chain hydrogen bonds with strand F. (B) Interatomic hydrogen bonds (blue) and interresidue hydrophobic interactions (black) that are diagnostic of strand H dissociation are shown as a function of time and organized according to the specific structural changes they are associated with. To see this figure in color, go online.

Dissociation of strand D

Conformational changes to strand D were the next-most-common structural change to TTR monomers in this data set (Fig. 4). In the crystallographic conformation, strand D associates with strand A via main-chain hydrogen bonds, a salt bridge, and several hydrophobic interactions within the core. At the N-terminal end of strand D, residues 50–53 form a tight hairpin turn, and at the C-terminal end, H56 forms a β-bulge and residues in the DE loop form a quasihelix. In some MD simulations, conformational changes to strand D and its neighboring loops resulted in the formation of nonnative structures around strand D and the exposure of strand A to solvent. As an example of strand D dissociation, we analyzed the dynamics of this region of run 3 of the TTRD18G simulations (Fig. 6). Dissociation of strand D began at 48 ns with the loss of structure and subsequent expansion of the hairpin turn formed by residues 50–53. This resulted in a loss of native main-chain hydrogen bonds, the formation of nonnative side-chain contacts between residues 11 and 55 and 10 and 53, and a shift of strand D toward the N-terminal end of strand A. The resulting conformation allowed strand D to form nonnative interactions with N-terminal residues as well as main-chain hydrogen bonds with S46 and G47 (located in strand C). At 160 ns, the CD loop and the quasihelical DE loop unfolded, which allowed for formation of a nonnative CD hairpin as residues F44 and L58 came into contact with one another. Hairpin formation induced α-sheet structure in strands C and D in this simulation, but only after the CD and DE loops unfolded. This also induced α-sheet structure in the AB loop and to some extent in strand B; however, nativelike interactions in the CBEF sheet likely prevented complete formation of α-sheet structure in strand B, as discussed previously (Fig. 6; (39)).

Figure 6.

Dynamics of strand dissociation at the D:A interface. In run 3 of the D18G TTR simulations, strand D dissociated from the DAGH sheet and formed a nonnative α-sheet hairpin with strand C. (A) Snapshots from the simulation illustrate the sequence of events associated with the dissociation of strand D. (B) Interatomic hydrogen bonds (blue) and interresidue hydrophobic interactions (black) that are diagnostic of strand D dissociation are shown as a function of time and organized according to the specific structural changes they are associated with. To see this figure in color, go online.

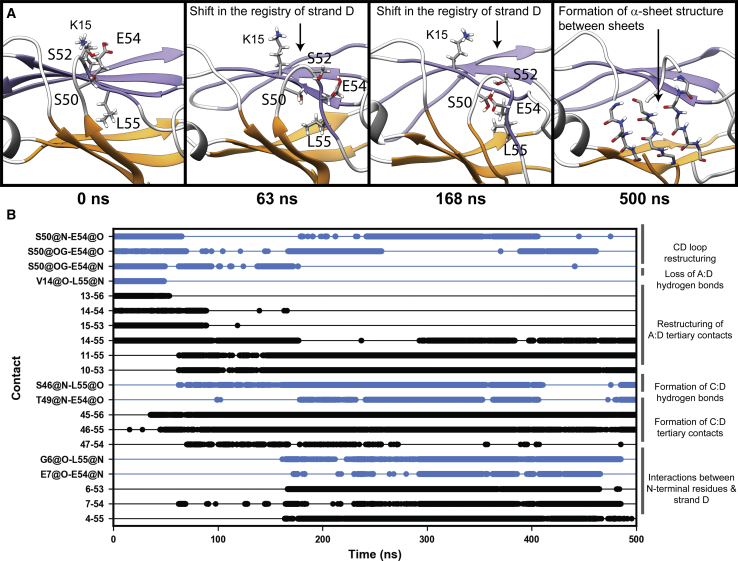

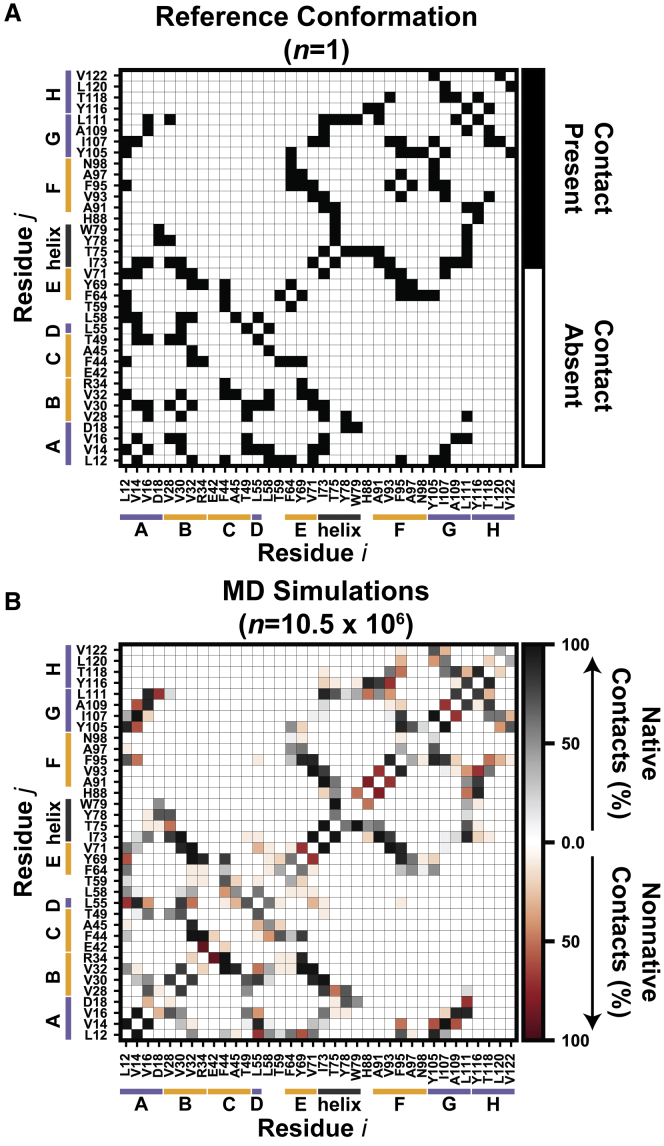

Hydrophobic core packing

In the MD simulations described here, strand dissociation was associated with changes or disruptions to hydrophobic packing in the core of TTR. We previously investigated interactions made by solvent-exposed side chains in the DAGH and CBEF sheets by tracking the fraction of the net simulation time that solvent-exposed side chains interacted with one another. We found that solvent-exposed side chains in the CBEF sheet formed nativelike interactions, whereas solvent-expose side chains in the DAGH sheet formed transient, nonnative interactions (39). Here, we investigated coupling between the side-chain interaction network in the hydrophobic core and conformational changes to TTR (Fig. 7). As expected, the side-chain-side-chain interaction network formed among residues in the hydrophobic core was more consistent than that formed by surface-facing residues. Overall, contacts formed between residues in the interior strands (A, B, E, and G) were the most likely to be maintained. For example, contacts formed between V32-V71 and V14-I107 were maintained for 100 and 99% of the time during MD. Of the 95 residue contact pairs present in the reference structure, 37% were maintained for >80% of the aggregate simulation time, 52% were maintained for 20–80% of the aggregate simulation time, and 12% were maintained for <20% of the aggregate simulation time (Fig. 7; Table S1).

Figure 7.

Changes in the side-chain-side-chain interaction network in the hydrophobic core of TTR monomers under amyloidogenic conditions. (A) The binary contact map shows the presence or absence of side-chain-side-chain interactions in the crystallographic reference structure. (B) The contact map constructed from the MD ensemble shows the percentage of the aggregate simulation time for which side-chain-side-chain interactions were present. “Native” interactions, or those present in the crystallographic reference structure, are colored on a scale from white (never in contact) to black (always in contact). “Nonnative” interactions, or those present only in the MD ensemble, are colored on a scale from white (never in contact) to red (always in contact). To see this figure in color, go online.

Loss of interactions in the hydrophobic core led to changes in the tertiary structure of TTR. For example, the Y78-L111 contact reflected the presence of nativelike geometry within the GH and EF loops, but it was lost upon strand dissociation and subsequent projection of the GH loop into solvent. Of the 45 residue contact pairs not observed in the reference structure, 4% were present for >80% of the aggregate simulation time, 67% were observed for 20–80% of the aggregate simulation time, and 29% were present for <20% of the aggregate simulation time (Fig. 7; Table S1).

Overall, the least nativelike regions of the hydrophobic core were the edge strands, as well as the end of the sandwich farthest from the α-helix. This region of TTR contains three inward-facing Phe residues (F44 in strand C, F64 in the DE loop, and F95 in strand F) that are protected from solvent by the DE and FG loops. In the crystallographic structure, these aromatic residues form contacts with many neighbors within the hydrophobic core, but those contacts were disrupted by rearrangements to the hydrophobic core packing that are associated with structural changes in TTR. In the reference structure, F44 forms contacts with six residues, but during MD, contacts with four of those were diminished and novel contacts were formed with two residues (Table 1). Thus, as TTR formed nonnative conformations, F44 made fewer interactions with the interior hydrophobic core in favor of interactions with residues in the edge strands C and F. Similar patterns were observed for F64 and F95 (Table 1). The native interactions made by F64 that were lost were not replaced by new contacts. For F95, there was trade-off in the set of contacts formed: lost interactions with residues in strands G and E were replaced by interactions in strand H (Fig. 7; Table 1).

Table 1.

Contacts Formed by Phe Residues in the Hydrophobic Core

| Phe 44 |

Phe 64 |

Phe 95 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact Partner | Contact Frequency (%) | Contact Partner | Contact Frequency (%) | Contact Partner | Contact Frequency (%) |

| Contact Pairs Observed in the Reference Structure and MD Simulations | |||||

| L12 | 26 | L12 | 60 | L12 | 70 |

| V32 | 97 | F44 | 27 | F64 | 26 |

| R34 | 98 | T59 | 41 | Y69 | 88 |

| T59 | 71 | Y69 | 64 | V71 | 88 |

| F64 | 27 | F95 | 26 | V93 | 86 |

| Y69 | 77 | A97 | 51 | A97 | 40 |

| – | – | N98 | 10 | Y105 | 86 |

| – | – | Y105 | 54 | I107 | 84 |

| Contact Pairs Observed in MD Simulations Only | |||||

| E42 | 20 | V32 | 14 | V14 | 50 |

| L58 | 40 | L58 | 13 | A109 | 22 |

| – | – | – | – | T118 | 46 |

| – | – | – | – | L120 | 34 |

Comparison with experimental data

Solid-state NMR with selective labeling schemes has provided interatomic distances for both native (i.e., the natively folded tetramer) and fibril (i.e., mature fibrils) states of TTR (36,37). Interatomic distances were measured via selective labeling of specific C and Cα residue pairs. In the NMR experiments, a crosspeak indicated that the specified pair of atoms were within 6 Å of one another. Analysis of residue pairs with interatomic distances between 4 and 6 Å in the native state provides insights into structural changes that occur during fibril formation. Most crosspeaks were observed in both the native and fibril states of TTR: L12-Y105, H31-S46, F33-Y69, L55-M13, F95-Y69, L110-Y116, L111-Y116, and V121-Y105. Other crosspeaks were present in the native state but absent in the fibril state of TTR: P24-L17 and F87-Y114. Some of the interatomic distances were dependent on the TTR variant studied and the conditions of the experiment (A36-D39, G47-V30, I73-V30, I73-A91, I107-V14) (Fig. S6). The conservation of interatomic distances in both the native and fibril states suggests a preservation of nativelike structure in the fibril state, and increased interatomic distances is indicative of a loss of structure in the AB and GH loops.

We calculated whether the ensembles produced by our simulations corresponded with the NMR-derived interatomic distances. Importantly, this is not a direct comparison, because the experimental data measured interatomic distances in the native or fibril states, whereas our MD-derived ensembles comprise nonnative TTR monomers that have not aggregated. This comparison tests how well our MD-derived TTR conformations agree with experimentally obtained distances for mature TTR fibrils. We calculated interatomic distances on a per-simulation basis. Data from the three WT simulations, which best match the NMR experiments, are presented in Table 2, and the results from mutant simulations are in Table S2. The computational results were in good agreement with the experimental results (Table 2). Most of the interatomic distances that were <6 Å in both the native and fibril states of TTR were also <6 Å in the WT MD ensembles (Table 2). The correspondence of these distances suggests that MD did not produce conformations that were “too unfolded” or “incorrectly” unfolded and that an appropriate level of nativelike structure was preserved. The computational results were also in agreement with two of the interatomic distances <6 Å in the native state but >6 Å in the fibril state of TTR: F87-Y114 and A36-D39 (Table 2). These large distances are indicative of the conformational changes to the GH and BC loops that occurred during MD. The P24-L17 distance, which probes the structure of the AB loop, was <6 Å in the WT simulations but was >6 Å in three of the mutant simulations (one simulation each from the L58H, Y69H, and V122I replicates, Table S2). This suggests that unfolding of some regions, such as the AB loop, occur over longer timescales than have been probed by MD or are a direct consequence of the specific environments where the solid-state NMR data were collected.

Table 2.

Interatomic Distances Measured by NMR or from the Wild-Type MD Simulations

| Atom Pairs | X Raya (Å) | NMR (Native, Å) | NMR (Fibril, Å) | WT MD (Run 1, Å) | WT MD (Run 2, Å) | WT MD (Run 3, Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L12@C-Y105@Cα | 5.7 | <6 | <6 | 6.2 | 5.6 | 6.4 |

| P24@C-L17@Cα | 4.6 | <6 | >6 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 5.4 |

| H31@C-S46@Cα | 5.1 | <6 | <6 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.4 |

| F33@C-Y69@Cα | 4.3 | <6 | <6 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.5 |

| A36@C-D39@Cα | 4.5 | <6b | >6b | 7.2 | 7.2 | 7.2 |

| G47@C-V30@Cα | 4.8 | <6 | <6c | 4.8 | 6.3 | 4.9 |

| L55@C-M13@Cα | 4.7 | <6 | <6 | 4.4 | 6.3 | 5.2 |

| I73@C-V30@Cα | 5.4 | <6 | <6c | 5.6 | 5.4 | 5.1 |

| I73@C-A91@Cα | 5.1 | <6 | <6d | 5.1 | 5.5 | 5 |

| F87@C-Y114@Cα | 6.1 | <6 | >6 | 6.9 | 7.3 | 7.1 |

| F95@C-Y69@Cα | 5 | <6 | <6 | 6 | 4.8 | 4.8 |

| I107@C-V14@Cα | 4.4 | <6 | <6d | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.4 |

| L110@C-Y116@Cα | 4.5 | <6 | <6 | 9.8 | 5.7 | 5.9 |

| L111@C-Y116@Cα | 5.3 | <6 | <6 | 9.2 | 4.8 | 5.1 |

| V121@C-Y105@Cα | 4.7 | <6 | <6 | 10 | 5.4 | 4.8 |

Chain A of PDB: 1TTA was used.

This distance was dependent on the mixing time.

This distance was dependent on the TTR variant.

This distance was calculated for V30M TTR.

Although these selective labeling schemes have provided detailed structural information, there are too few restraints to allow derivation of a structure. Additionally, there were no distances found to be >6 Å in the native state but <6 Å in the fibril state of TTR. Instead, insights from the data set have been used to refine models of TTR during aggregation. To aid in the refinement of models of TTR during aggregation and to provide testable hypotheses that can be used to assess computational results, we have calculated additional interatomic distances from our simulations that could be informative. We calculated all 16,129 possible interatomic C-Cα distances from the MD ensemble as well as the interatomic distances in chain A of the 1TTA x-ray structure. For the MD ensemble calculation, the results were averaged according to Eq. 1 (see Methods). Of those, 15,462 (95.8%) distances were >6 Å in both the crystallographic monomers within tetrameric native structure and the MD-derived monomeric, nonnative state. The remaining interatomic distances have the potential to provide clues into the structure of TTR during fibril formation. In total, 481 (3%) distances were <6 Å in both the native monomer as well as in nonnative monomers and indicate a preservation of native structure during aggregation; 94 (0.6%) distances were >6 Å in the native monomer but <6 Å in nonnative monomers and indicate the formation of nonnative structure during aggregation; 92 (0.6%) distances were <6 Å in the native monomer but >6 Å in nonnative monomers and indicate a loss of native structure during aggregation. Table 3 lists interatomic distances culled from this data set that could be used to evaluate computational results and provide new insights into structural changes that precede the formation of TTR fibrils.

Table 3.

Predicted Interatomic Distances

| Atom 1 | Atom 2 | Reference Distance | MD Ensemble Distance | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A25 @ C | 16 @ Cα | <6 | >6 | AB loop disorder |

| A25 @ C | T49 @ Cα | <6 | >6 | AB/CD loop separation |

| G53 @ C | P24 @ Cα | <6 | >6 | strand D registry |

| L58 @ C | A45 @ Cα | <6 | >6 | strand D registry |

| V65 @ C | N98 @ Cα | <6 | >6 | strand F unfolding |

| T75 @ C | H90 @ Cα | <6 | >6 | strand F unfolding |

| N98 @ C | P102 @ Cα | <6 | >6 | FG loop disorder |

| P11 @ C | G57 @ Cα | >6 | <6 | strand D registry |

| L55 @ C | T49 @ Cα | >6 | <6 | strand C/D association |

Our MD results also showed that it is possible for conformational changes to occur that result in nonnative structures that yield interatomic distances that would produce NMR signals indicative of native structure. For example, in the third V122I simulation, strand C, strand D, and the CD loop formed nonnative conformations; however, this simulation agreed with all experimentally derived results for the native state. Importantly, the L55-M13 interatomic distance was <6 Å (Fig. 8). Experimentally, this finding was interpreted as a preservation of nativelike structure in the interface between strands D and A. Our simulations show that although the interactions in this interface are nativelike, there are several structural differences relative to the crystal structure, including the exposure of the C-terminal end of strand A and a change in the registry of the D:A interface (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

The preservation of an interatomic distance does not guarantee preservation of native structure. The presence of a crosspeak in both the native and fibrillar states has been interpreted as a preservation of nativelike structure in the amyloid states of TTR. However, this is not necessarily the case. Here, a snapshot of the V122I run 3 simulation is compared against the reference crystal structure to highlight that a distance (L55@C-M13@Cα) can be <6 Å even though the structure is not native. In this example, strand D has adopted a nonnative structure: the CD loop is disordered, and the registry of strand D versus strand A has been altered relative to the reference crystal structure, yet the interatomic distance is preserved. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

Conformational changes in the early stages of TTR amyloidogenesis

The available experimental data have variously suggested that destabilization of either the CBEF or DAGH sheet initiates TTR unfolding during amyloidogenesis. These results have been obtained from distinct TTR sequences under subtly different environmental conditions and are likely confounded by the presence of multiple conformational states. Previous structural studies of TTR have indicated varying degrees of native structure within TTR aggregates, yet the results have been contradictory. One explanation for these contradictions is that these studies have been performed under different environmental conditions, which are known to affect the structure of mature TTR fibrils (68). Additionally, sample preparation methods may have resulted in a range of conformational states (e.g., tetramer, monomer, nonnative and aggregation-competent monomers, oligomers, and fibrils) that contributed to the reported signals.

The results of a recent series of solution- and solid-state NMR experiments can be compared with the MD results presented here. Relaxation-dispersion experiments using solution NMR of intermediate TTR species during aggregation have predicted nativelike structures for residues in the CBEF sheet, whereas the DAGH sheet was shown to undergo conformational fluctuations at and below millisecond timescales (35,36,38). We speculate that these fluctuations may correspond to conversion to α-sheet structure, as was observed in our simulations (39). In our MD study, the CBEF sheet retained native structure: the edge strands in the CBEF sheet had a reduced propensity to dissociate relative to the DAGH sheet, and the side-chain solvent-exposed contact network was more consistent. Solid-state NMR experiments using selective C and Cα labeling schemes mapped the degree of nativelike structure present in mature TTR fibrils (36,37). The resulting crosspeaks showed nativelike CBEF and DAGH structures within fibrils, with the potential for dissociation of strand D and exposure of strand A. Although there was good correspondence between experimental and computational results, the analysis has pointed to a few counterexamples that limit the degree to which these data may demonstrate true native structure. Furthermore, our analysis has revealed several potentially interesting residue pairs that merit further investigation.

Overall, interpretation of the experimental and computational results has produced a clearer picture of the conformational changes of transthyretin during amyloidogenesis. In a solution NMR heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectrum of nonnative TTR intermediates, the observable resonances were mapped to residues in the C, B, E, and F strands (35), suggesting nativelike structure in the CBEF sheet and the presence of conformational fluctuation in the DAGH sheet. Follow-up solid-state NMR experiments showed that the AB loop becomes disordered in the fibril (37). The MD results, which track the behavior of single molecules, suggest that conformational changes within the DAGH sheet are more likely because this region had high propensity to form α-sheet as well as the greatest propensity for strand dissociation (both strand D and strand H). Our observation that strand H was the most dynamic edge strand is also supported by an NMR structure of F87M/L110M TTR, in which strand H is dissociated from the DAGH sheet (69). The MD simulations also showed that conformational changes to the edge strands of the CBEF sheet also occur but on a slower timescale than in the DAGH sheet (39).

Changes in tertiary structure are coupled to changes in secondary structure

Prior MD studies showed that tertiary contacts can influence the formation and dissolution of secondary structure elements and vice versa. We observed tertiary contact-assisted secondary structure formation during folding of barnase and protein A (70, 71, 72, 73) and during misfolding of the prion protein (27). In this TTR study, interactions at the tertiary structure level influenced pathological main-chain conformational changes. In D18G run 3, unfolding of strand D led to α-sheet conversion in strands C and B. In WT run 2, the rearrangement of strand D and the partial dissociation of strand C led to a separation of strands B and E near the α-helix in TTR, and conversion to α-sheet for residues in this region followed. In run 2 of the L111M simulations, the BC turn and surrounding residues moved almost perpendicular to the CBEF sheet. In V122I run 3, the AB loop and α-helix separated from one another. This allowed for α-sheet conversion in the C-terminal end of the AB loop and N-terminal end of strand B, which later propagated to strands E and F.

Interpretation of our MD simulations alongside prior experimental studies provides several clues into the conformational changes that lead to the formation of aggregation-competent conformations (Fig. 9). Our MD simulations indicate that early changes to TTR’s secondary structure involve a conversion from β-sheet to α-sheet in the DAGH sheet, followed by conversion in the CBEF sheet. Over longer timescales, there were changes to the tertiary structure—most commonly the dissociation of the edge strands. Strands D and H were the most likely to dissociate, partial dissociation of strand C occurred but was rare, and strand F primarily retained native structure. The conformations of the edge strands may determine the structures of oligomers formed during aggregation.

Figure 9.

Summary of conformational changes to TTR monomers that precede aggregation. During the early stages of amyloidogenesis, the secondary structure of the DAGH and CBEF sheets was disrupted: native β-sheet secondary structure was replaced with nonnative, aggregation-prone α-sheet. This conversion was more rapid for the DAGH sheet; complete α-sheet conversion was not observed in the CBEF sheet. Conversion in the CBEF sheet may occur over longer timescales and appears coupled to disruptions in the tertiary structure and the conformation of the DAGH sheet. Formation of α-sheet structure may aid in the aggregation of monomers and revert to β-sheet structure in more stable, fibrillar species. Also, the edge strands in TTR dissociate from their sheets: dissociation of strands H and D occurs more rapidly than dissociation of strands C and F. Over longer timescales, these strands may remain dissociated, refold to a native conformation, or refold to a nonnative conformation. To see this figure in color, go online.

Solid-state NMR experiments have yielded several structural insights into fibrillar conformations of TTR; however, that data set did not include interactions that were absent in the native state but present in the fibril state of TTR. We have predicted several residue pairs from our simulations for which a signal should be absent in the native state of TTR and may be present in oligomeric or fibrillar states of TTR. These can be tested experimentally, which has the potential to assess our computational results and provide additional insight into TTR during aggregation. These simulations have also identified structural regions of TTR prone to misfolding. We speculate that knowledge of these specific regions may allow for the design of TTR variants with altered stabilities. Such constructs could be used to further probe amyloid formation by TTR. Mutations such as A120L and A45L would promote retention of nativelike structure in the H and C strands, respectively, and inhibit edge strand dissociation. Some mutations to residues in the DAGH sheet (such as A108, S117, and A120) may stabilize it, preventing secondary structure conversion and aggregation. Similarly, mutations to residues in the CBEF sheet (such as F33, K70, E72, and N98) may destabilize TTR and accelerate aggregation.

Conclusions

The heterogeneous and dynamic nature of species populated during amyloidogenesis has been a perennial frustration. The available experimental data that probe the structures of fibrillar states are often low resolution or incomplete. Here, we have employed computational methods that track the dynamics of single molecules over time to better assess the early dynamics that result in nonnative monomeric TTR conformations. Our computational results are in good agreement with the available experimental data. Structural rearrangements and dissociation of the edge strands in TTR were the most common conformational change to TTR monomers. Furthermore, these simulations point to the loss of native structure in the DAGH sheet as an initial event in the formation of nonnative monomers. Finally, we have shown that results from our simulations can in turn be used to design experiments or mutations to TTR that could further refine models of toxic amyloid species.

Author Contributions

M.C.C. and V.D. designed the research study. M.C.C. performed the research described here. M.C.C. and V.D. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GMS R01 95808) to V.D., the Bioengineering Cardiovascular Training Grant (National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering T32EB001650) to M.C.C., and the University of Washington Department of Bioengineering. The authors thank the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, supported by the Department of Energy Office of Biological Research, which is supported by the US Department of Energy under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231, for providing computing time. This work also used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) resource COMET through allocation MCB160012. XSEDE is supported by National Science Foundation grant number ACI-1548562. Molecular graphics were performed with UCSF Chimera, which was developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, with support from National Institutes of Health P41-GM103311.

Editor: Amedeo Caflisch.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.08.043.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Knowles T.P.J., Vendruscolo M., Dobson C.M. The amyloid state and its association with protein misfolding diseases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:384–396. doi: 10.1038/nrm3810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleem A., Daggett V. Structural and functional diversity among amyloid proteins: agents of disease, building blocks of biology, and implications for molecular engineering. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017;114:7–20. doi: 10.1002/bit.26059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson M.D., Buxbaum J.N., Westermark P. Amyloid nomenclature 2018: recommendations by the International Society of Amyloidosis (ISA) nomenclature committee. Amyloid. 2018;25:215–219. doi: 10.1080/13506129.2018.1549825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haass C., Selkoe D.J. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shea D., Hsu C.-C., Daggett V. α-Sheet secondary structure in amyloid β-peptide drives aggregation and toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:8895–8900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1820585116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen R.C., Aisen P., Jack C.R., Jr. Mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer disease in the community. Ann. Neurol. 2013;74:199–208. doi: 10.1002/ana.23931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gandy S., Simon A.J., Ehrlich M.E. Days to criterion as an indicator of toxicity associated with human Alzheimer amyloid-beta oligomers. Ann. Neurol. 2010;68:220–230. doi: 10.1002/ana.22052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batzli K.M., Love B.J. Agitation of amyloid proteins to speed aggregation measured by ThT fluorescence: a call for standardization. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2015;48:359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hurshman A.R., White J.T., Kelly J.W. Transthyretin aggregation under partially denaturing conditions is a downhill polymerization. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7365–7381. doi: 10.1021/bi049621l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doig A.J., Derreumaux P. Inhibition of protein aggregation and amyloid formation by small molecules. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2015;30:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bulawa C.E., Connelly S., Labaudinière R. Tafamidis, a potent and selective transthyretin kinetic stabilizer that inhibits the amyloid cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:9629–9634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121005109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cremades N., Dobson C.M. The contribution of biophysical and structural studies of protein self-assembly to the design of therapeutic strategies for amyloid diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018;109:178–190. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eichner T., Kalverda A.P., Radford S.E. Conformational conversion during amyloid formation at atomic resolution. Mol. Cell. 2011;41:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loureiro R.J.S., Vila-Viçosa D., Faísca P.F.N. The early phase of β2m aggregation: an integrative computational study framed on the D76N mutant and the ΔN6 variant. Biomolecules. 2019;9:366. doi: 10.3390/biom9080366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moraitakis G., Goodfellow J.M. Simulations of human lysozyme: probing the conformations triggering amyloidosis. Biophys. J. 2003;84:2149–2158. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75021-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armen R.S., Alonso D.O.V., Daggett V. Anatomy of an amyloidogenic intermediate: conversion of beta-sheet to alpha-sheet structure in transthyretin at acidic pH. Structure. 2004;12:1847–1863. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armen R.S., DeMarco M.L., Daggett V. Pauling and Corey’s alpha-pleated sheet structure may define the prefibrillar amyloidogenic intermediate in amyloid disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:11622–11627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401781101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armen R.S., Daggett V. Characterization of two distinct β2-microglobulin unfolding intermediates that may lead to amyloid fibrils of different morphology. Biochemistry. 2005;44:16098–16107. doi: 10.1021/bi050731h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Narang S.S., Shuaib S., Goyal B. Assessing the effect of D59P mutation in the DE loop region in amyloid aggregation propensity of β2-microglobulin: a molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018;119:782–792. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zorgati H., Larsson M., Robinson R.C. The role of gelsolin domain 3 in familial amyloidosis (Finnish type) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:13958–13963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1902189116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kazmirski S.L., Isaacson R.L., Fersht A.R. Loss of a metal-binding site in gelsolin leads to familial amyloidosis-Finnish type. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nsb745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steward R.E., Armen R.S., Daggett V. Different disease-causing mutations in transthyretin trigger the same conformational conversion. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2008;21:187–195. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzm086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang W., Zhang S., Karplus M. Kinetic control of dimer structure formation in amyloid fibrillogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12916–12921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402634101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urbanc B., Cruz L., Dokholyan N.V. Molecular dynamics simulation of amyloid β dimer formation. Biophys. J. 2004;87:2310–2321. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.040980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fogolari F., Corazza A., Esposito G. Molecular dynamics simulation of β2-microglobulin in denaturing and stabilizing conditions. Proteins. 2011;79:986–1001. doi: 10.1002/prot.22940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jafari M., Mehrnejad F. Molecular insight into human lysozyme and its ability to form amyloid fibrils in high concentrations of sodium dodecyl sulfate: a view from molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alonso D.O., DeArmond S.J., Daggett V. Mapping the early steps in the pH-induced conformational conversion of the prion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:2985–2989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061555898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennion B.J., DeMarco M.L., Daggett V. Preventing misfolding of the prion protein by trimethylamine N-oxide. Biochemistry. 2004;43:12955–12963. doi: 10.1021/bi0486379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skeby K.K., Sørensen J., Schiøtt B. Identification of a common binding mode for imaging agents to amyloid fibrils from molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:15114–15128. doi: 10.1021/ja405530p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemkul J.A., Bevan D.R. The role of molecular simulations in the development of inhibitors of amyloid β-peptide aggregation for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2012;3:845–856. doi: 10.1021/cn300091a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hörnberg A., Eneqvist T., Sauer-Eriksson A.E. A comparative analysis of 23 structures of the amyloidogenic protein transthyretin. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;302:649–669. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berman H.M., Westbrook J., Bourne P.E. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eneqvist T., Andersson K., Sauer-Eriksson A.E. The β-slip: a novel concept in transthyretin amyloidosis. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1207–1218. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olofsson A., Ippel J.H., Öhman A. Probing solvent accessibility of transthyretin amyloid by solution NMR spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:5699–5707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lim K.H., Dyson H.J., Wright P.E. Localized structural fluctuations promote amyloidogenic conformations in transthyretin. J. Mol. Biol. 2013;425:977–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim K.H., Dasari A.K.R., Wemmer D.E. Structural changes associated with transthyretin misfolding and amyloid formation revealed by solution and solid-state NMR. Biochemistry. 2016;55:1941–1944. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lim K.H., Dasari A.K.R., Wemmer D.E. Solid-state NMR studies reveal native-like β-sheet structures in transthyretin amyloid. Biochemistry. 2016;55:5272–5278. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leach B.I., Zhang X., Wright P.E. NMR measurements reveal the structural basis of transthyretin destabilization by pathogenic mutations. Biochemistry. 2018;57:4421–4430. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Childers M.C., Daggett V. Drivers of α-sheet formation in transthyretin under amyloidogenic conditions. Biochemistry. 2019;58:4408–4423. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang M., Lei M., Huo S. Peptide plane can flip in two opposite directions: implication in amyloid formation of transthyretin. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:5829–5833. doi: 10.1021/jp0570420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodrigues J.R., Simões C.J.V., Brito R.M.M. Potentially amyloidogenic conformational intermediates populate the unfolding landscape of transthyretin: insights from molecular dynamics simulations. Protein Sci. 2010;19:202–219. doi: 10.1002/pro.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang M., Lei M., Huo S. Initial conformational changes of human transthyretin under partially denaturing conditions. Biophys. J. 2005;89:433–443. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.059642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang X., Smith C.S., Kelly J.W. An engineered transthyretin monomer that is nonamyloidogenic, unless it is partially denatured. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11442–11452. doi: 10.1021/bi011194d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yokoyama T., Hanawa Y., Mizuguchi M. Stability and crystal structures of His88 mutant human transthyretins. FEBS Lett. 2017;591:1862–1871. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamilton J.A., Steinrauf L.K., Steen L. The x-ray crystal structure refinements of normal human transthyretin and the amyloidogenic Val-30-->Met variant to 1.7-A resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:2416–2424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scouras A.D., Daggett V. The Dynameomics rotamer library: amino acid side chain conformations and dynamics from comprehensive molecular dynamics simulations in water. Protein Sci. 2011;20:341–352. doi: 10.1002/pro.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Towse C.-L., Rysavy S.J., Daggett V. New dynamic rotamer libraries: data-driven analysis of side-chain conformational propensities. Structure. 2016;24:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palaninathan S.K. Nearly 200 X-ray crystal structures of transthyretin: what do they tell us about this protein and the design of drugs for TTR amyloidoses? Curr. Med. Chem. 2012;19:2324–2342. doi: 10.2174/092986712800269335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lai Z., Colón W., Kelly J.W. The acid-mediated denaturation pathway of transthyretin yields a conformational intermediate that can self-assemble into amyloid. Biochemistry. 1996;35:6470–6482. doi: 10.1021/bi952501g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCutchen S.L., Colon W., Kelly J.W. Transthyretin mutation Leu-55-Pro significantly alters tetramer stability and increases amyloidogenicity. Biochemistry. 1993;32:12119–12127. doi: 10.1021/bi00096a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anandakrishnan R., Aguilar B., Onufriev A.V. H++ 3.0: automating pK prediction and the preparation of biomolecular structures for atomistic molecular modeling and simulations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W537–W541. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beck D.A.C., McCully M.E., Daggett V. University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 2000. In Lucem Molecular Mechanics (in Lucem Molecular Mechanics (ilmm) 2000-2020) [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beck D.A.C., Daggett V. Methods for molecular dynamics simulations of protein folding/unfolding in solution. Methods. 2004;34:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Childers M.C., Daggett V. Validating molecular dynamics simulations against experimental observables in light of underlying conformational ensembles. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2018;122:6673–6689. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b02144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kell G.S. Precise representation of volume properties of water at one atmosphere. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 1967;12:66–69. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levitt M., Hirshberg M., Daggett V. Potential energy function and parameters for simulations of the molecular dynamics of proteins and nucleic acids in solution. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995;91:215–231. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levitt M., Hirshberg M., Daggett V. Calibration and testing of a water model for simulation of the molecular dynamics of proteins and nucleic acids in solution. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1997;101:5051–5061. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beck D.A.C., Armen R.S., Daggett V. Cutoff size need not strongly influence molecular dynamics results for solvated polypeptides. Biochemistry. 2005;44:609–616. doi: 10.1021/bi0486381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Borg I., Groenen P.J.F. Springer; New York, NY: 2005. Modern Multidimensional Scaling: Theory and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pedregosa F., Varoquaux G., Duchesnay É. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011;12:2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Ferrin T.E. UCSF chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hunter J.D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007;9:90–95. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kruskal J.B. Multidimensional scaling by optimizing goodness of fit to a nonmetric hypothesis. Psychometrika. 1964;29:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levitt M. Molecular dynamics of native protein. II. Analysis and nature of motion. J. Mol. Biol. 1983;168:621–657. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li A., Daggett V. Characterization of the transition state of protein unfolding by use of molecular dynamics: chymotrypsin inhibitor 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:10430–10434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li A., Daggett V. Identification and characterization of the unfolding transition state of chymotrypsin inhibitor 2 by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;257:412–429. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li A., Daggett V. Molecular dynamics simulation of the unfolding of barnase: characterization of the major intermediate. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;275:677–694. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ihse E., Suhr O.B., Westermark P. Variation in amount of wild-type transthyretin in different fibril and tissue types in ATTR amyloidosis. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 2011;89:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0695-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oroz J., Kim J.H., Zweckstetter M. Mechanistic basis for the recognition of a misfolded protein by the molecular chaperone Hsp90. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:407–413. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bond C.J., Wong K.B., Daggett V. Characterization of residual structure in the thermally denatured state of barnase by simulation and experiment: description of the folding pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:13409–13413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alonso D.O., Daggett V. Staphylococcal protein A: unfolding pathways, unfolded states, and differences between the B and E domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:133–138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wong K.B., Clarke J., Daggett V. Towards a complete description of the structural and dynamic properties of the denatured state of barnase and the role of residual structure in folding. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;296:1257–1282. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scott K.A., Alonso D.O.V., Daggett V. Importance of context in protein folding: secondary structural propensities versus tertiary contact-assisted secondary structure formation. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4153–4163. doi: 10.1021/bi0517281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.