Abstract

Fixed orthodontic appliances are common and effective tools to treat malocclusion. Adverse effects of these appliances, such as dental caries and periodontitis, may be associated with alteration of the microbiome. This study investigated the impact of these appliances on the dynamics of the oral microbiome. Seventy-one patients were selected. Supragingival plaque samples were collected before placement (T0) and six months after placement (T1). Saliva samples were collected at T0 and T1, and then when appliance removal (T2). Microbial DNA was analyzed by 16S rRNA meta-sequencing. The diversity analysis indicated dynamic changes in the structure of the oral microbiome. Taxonomic analysis at phylum level showed a significant increase in Bacteroidetes and Saccharibacteria (formally TM7) and decrease in Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria over time, in both plaque and saliva. Genus level analysis of relative abundance indicated a significant increase in anaerobic and facultative anaerobes in both plaque and saliva. Fixed orthodontic appliances induced measurable changes in the oral microbiome. This was characterized by an increase in relative abundance of obligate anaerobes, including periodontal pathogens. It can be concluded that this dysbiosis induced by fixed orthodontic appliances is likely to represent a transitional stage in the shift in microbiome from healthy to periodontitis.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Bacteriology, Microbial communities

Introduction

The mouth harbors more than 700 bacterial species, constituting one of the most diverse bacterial communities in the human body1. The mouth comprises complex structures of hard and soft tissue, such as teeth, tongue, gingiva, and palate; unique variation in oral microbiome structure is observed according to the different surface properties2,3.

Fixed orthodontic appliances are a common and effective tool used to treat malocclusion, but can be associated with secondary effects, such as a change of microbiome and subsequent infections. The complicated undercut shape of orthodontic appliances makes teeth cleaning more difficult and induces plaque accumulation as well as need for restorations4–6. Therefore, it has been suggested that the risk of white-spot lesions, dental caries, and periodontal complication are due to the change in oral microbiome. The incidence and prevalence rates of white-spot lesions in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment are high, but these are incipient carious lesions that can be remineralized by application of fluoride7. Previous studies have suggested that an increase in Streptococcus mutans bacterial counts, generally regarded as a major risk factor for dental caries, is associated with placement of fixed orthodontic appliances8–11.

It is understood that anaerobic microorganisms in plaque play a key role in the initiation and acceleration of periodontal diseases. Periodontal pathogens, such as Fusobacterium, Treponema, and Porphyromonas spp., have been detected in dental plaque around orthodontic appliances12. Furthermore, the frequency of Tannerella forsythia, Campylobacter rectus, and Prevotella nigrescens increased after placement of orthodontic appliances13. Severe clinical attachment loss during orthodontic treatment has also been reported14. These reports suggest that fixed orthodontic appliances may change the oral microbiome and have the potential to shift the bacterial ecosystem toward a pathogenic state. However, most previous reports have focused on only specific species and very few have focused on the microbiome and its dynamics, including unculturable bacteria, following orthodontic treatment.

Conventional methods of bacteriological identification, such as cultivation, present limitations to the analysis of microbial community structure and diversity, because the human bacterial flora contains many unculturable species. Emergence of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technology has enabled analysis and comparison of bacterial composition, including unculturable bacteria, with unprecedented depth compared to previous methodologies15. However, there are few reports about the relationship between orthodontic treatment and the dynamics of oral microbiome. In previous report using NGS, periodontal pathogens were highest during orthodontic treatment, but the data was confined about plaque16.

The aim of this study was to assess the changes in oral microbiome dynamics caused by fixed orthodontic appliances using 16S rRNA gene meta-sequencing of supragingival plaque and saliva.

Results

Operational taxonomic unit clustering and trim report

In total, 13,506,556 reads were generated from 144 samples, with an average length of 300.4. After sequence trimming, 8,284,029 high quality reads remained, with an average length of 222.5 bp. In plaque samples, 44 samples were successfully analyzed both at T0 and T1. In saliva samples, 16, 23, and 17 samples were successfully analyzed at T0, T1 and T2 respectively. We detected 983 OTUs in total, with an average of 341 OTUs per sample. The number of OTUs increased according to time course both in plaque (T0, 312 and T1, 321) and saliva samples (T0, 329; T1, 366; and T2, 376) though the difference was not significant.

Alpha and beta diversity

Alpha diversity, a measure of microbial community evenness and richness in each sample, was calculated and compared between time points (2 for plaque samples and 3 for saliva samples; Supplementary Fig. 1). The difference in number of OTUs in each sample relates to bacterial community diversity and the difference in number of reads at the end of clustering relates to diversity of sample DNA concentrations. Beta diversity, a measure of the variation of microbial communities between samples, was calculated and compared using Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA), based on the Jaccard index.

In plaque samples, bacterial diversity at T1 (321 ± 60 OTUs; range 214–430) was slightly more diverse than at T0 (312 ± 69; range 189–465; Supplementary Fig. 1a). There was no significant difference between upper and lower teeth at either T0 or T1. In saliva samples, there were no visible changes of bacterial community diversity between T0 (329 ± 54; range 240–409), T1 (366 ± 62; 271–481), and T2 (376 ± 60; range 214–430; appendix Supplementary Fig. 1b).

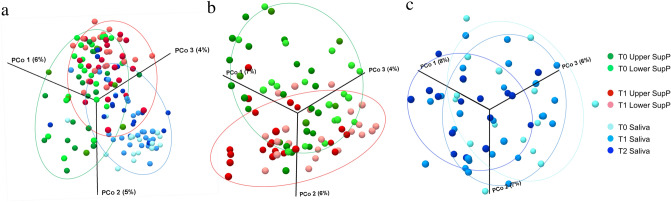

Combined analysis of the beta diversity of plaque and saliva showed that they consisted of different bacterial communities (Fig. 1a). Comparison of T0 with T1 plaque samples indicates that these two types of sample were apart from each other (Fig. 1b). We did not observe any obvious shifts in diversity between saliva samples at T0, T1, or T2 (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

Beta diversity of the oral microbiome following placement of fixed orthodontic devices. Beta diversity Jaccard index, based on principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of all samples (a), supragingival samples (b), and saliva samples (c). Green dots and red dots represent T0 and T1 samples, respectively and dark and light colors represent upper and lower teeth, respectively. In saliva samples, dark, middle, and light blue dots represent T0, T1, and T2 samples, respectively. T0 time point prior to placement of fixed orthodontic appliance, T1 time point approximately 6 months after the start of orthodontic treatment, T2 time point after appliance removal (average, 40 months after placement). These images were generated by CLC Genomics Workbench ver.9 (QIAGEN, Venlo, Netherlands) (https://www.qiagen.com/jp/products/discovery-and-translational-research/next-generation-sequencing/informatics-and-data/analysis-and-visualization/clc-genomics-workbench/#orderinginformation).

Taxonomic analysis

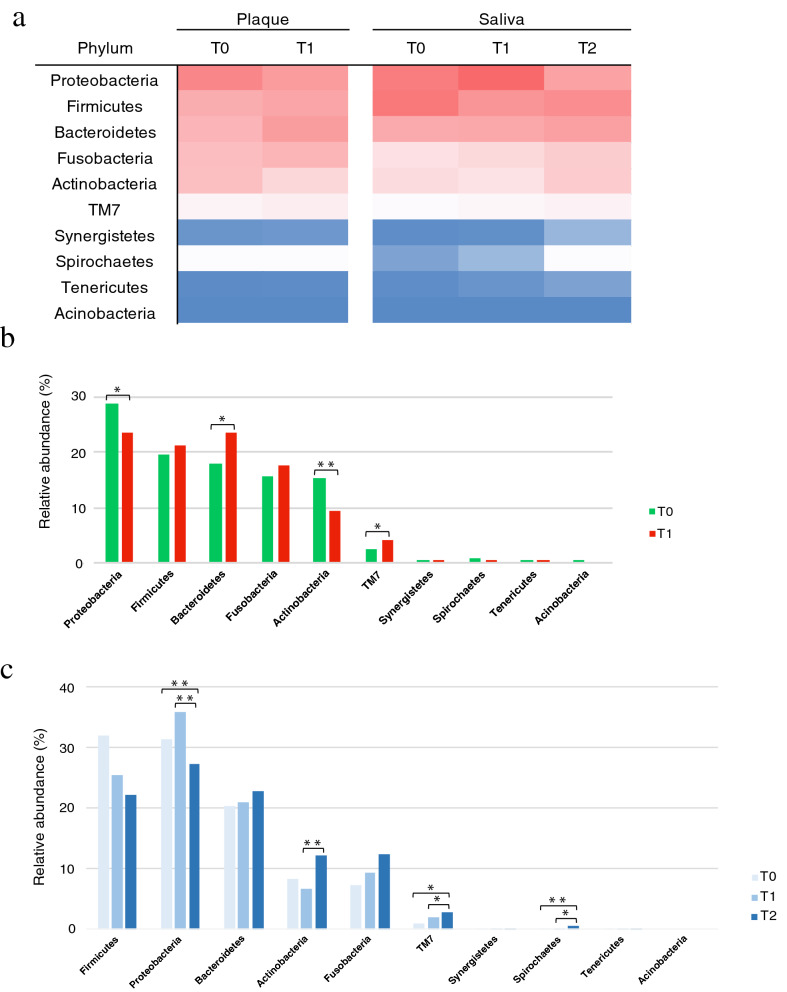

Bacterial structure, at phylum level, is shown in Fig. 2a as a heat map. The predominant phyla were Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Fusobacteria, and Actinobacteria, both in plaque and saliva. Phylum level bacterial distribution based on relative abundance in plaque samples is shown in Fig. 2b. The most dominant phylum both at T0 and T1 was Proteobacteria (28.74% and 23.56%, respectively), although Bacteroidetes distribution at T1 (23.44%) was similar to that of Proteobacteria. Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria significantly decreased at T1 (28.74–23.56% and 15.11–9.39%, respectively), whereas Bacteroidetes and TM7 significantly increased at T1 (17.78–23.44% and 2.59–4.08%, respectively).

Figure 2.

Bacterial population structure at phylum level. (a) Heat map of the relative abundance of bacteria from supragingival plaque and saliva, at phylum level, at each time point. (b) Relative abundance of bacteria in supragingival plaque, at phylum level. The green and red bars represent T0 and T1, respectively. (c) Relative abundance of bacteria in saliva, at phylum level. The dark, middle and light blue bars express T0, T1, and T2 respectively. Significant differences are indicated as *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 by Mann Whitney U (b) and Kruskal–Wallis (c) tests. T0 time point prior to placement of fixed orthodontic appliance, T1 time point approximately 6 months after the start of orthodontic treatment, T2 time point after appliance removal (average, 40 months after placement).

Phylum level bacterial distribution based on relative abundance in saliva samples is shown in Fig. 2c. Actinobacteria significantly increased from T1 (6.68%) to T2 (12.07%). TM7 significantly increased, in a time-dependent manner, from T0 (0.87%) to T1 (1.99%) and T2 (2.77%) and Spirochaetes demonstrated a similar trend (0.08%, 0.15%, and 0.64%, respectively). Fusobacteria and Bacteroidetes distribution also increased with time but the difference was not significant. Proteobacteria remained similar at T0 (31.22%) and T1 (35.75%) and significantly decreased at T2 (27.13%).

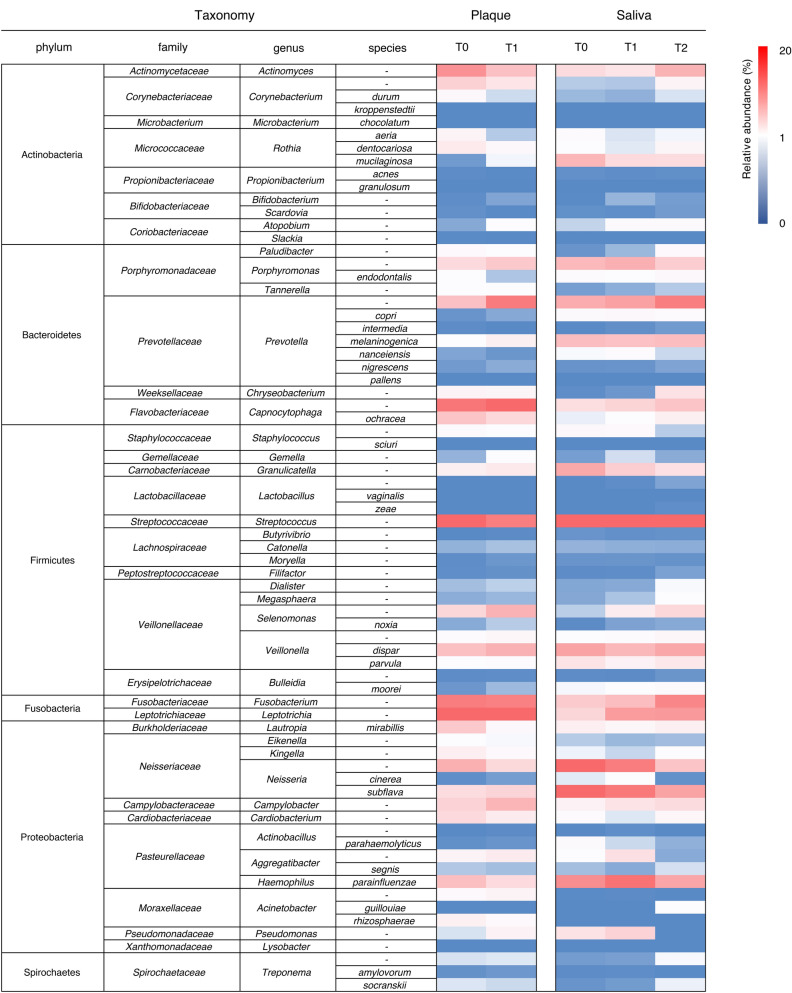

The overall microbiome in plaque and saliva is shown in Fig. 3 at phylum, family, genus, and species level. Predominant microbial distribution (> 5.0% of the relative abundance, dark blue scale in the heat map) in plaque samples at genus level were Leptotrichia, Streptococcus, Capnocytophaga, Fusobacterium, Prevotella, and Actinomyces. In saliva samples, predominant genera were Streptococcus, Neisseria, Haemophilus, Prevotella, and Veillonella. Capnocytophaga, Fusobacterium, and Leptotrichia spp. were more relatively abundant in supragingival plaque than in saliva. Conversely, Neisseria and Haemophilus spp. were more abundant in saliva.

Figure 3.

Bacterial population structure at genus or species level. Heat map of the relative abundance of bacteria in supragingival plaque and saliva, at genus or species level, at each time point. T0 time point prior to placement of fixed orthodontic appliance, T1 time point approximately 6 months after the start of orthodontic treatment, T2 time point after appliance removal (average, 40 months after placement).

Increased bacterial abundance in supragingival plaque with time are shown in Table 1a. Relative abundance of Prevotella, Porphyromonas, Capnocytophaga, Parvimonas, and Selenomonas spp., which are implicated in periodontal diseases, were significantly higher at T1 than T0. There was no significant difference in other bacteria, unrelated to periodontitis, between T0 and T1. Most of the bacteria which demonstrated increased abundance over time were obligate anaerobes.

Table 1.

List of the bacteria that showed dynamics.

| (a) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | RA at T0 (%) | RA at T1 (%) | p-value | Oxygen demand | Relevant pathological conditions | |

| Atopobium | – | 0.12 | 0.44 | 0.002** | Facultative anaerobic | Periodontitis, vaginosis | |

| Solobacterium | Moorei | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.006** | Obligate anaerobic | Periodontitis, dentoalveolar abscess | |

| Campylobacter | – | 2.77 | 4.48 | 0.006** | Facultative anaerobic | Periodontitis | |

| Capnocytophaga | – | 3.63 | 8.94 | 0.001** | Facultative anaerobic | Periodontitis, animal bite wounds | |

| Gemella | – | 0.16 | 0.45 | 0.047* | Facultative anaerobic | Endocarditis | |

| Leptotrichia | – | 10.83 | 14.04 | 0.112 | Obligate anaerobic | Endocarditis | |

| Moryella | – | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.002** | Obligate anaerobic | – | |

| Parvimonas | Micra | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.001** | Facultative anaerobic | Periodontitis, septic arthritis | |

| Porphyromonas | – | 2.42 | 3.35 | 0.070 | Obligate anaerobic | Periodontitis | |

| Prevotella | – | 3.81 | 7.69 | 0.001** | Obligate anaerobic | Periodontitis | |

| Prevotella | Melaninogentica | 0.52 | 1.18 | 0.048* | Obligate anaerobic | – | |

| Selenomonas | – | 2.54 | 4.61 | 0.001** | Obligate anaerobic | – | |

| Selenomonas | Noxia | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.036* | Obligate anaerobic | Periodontitis | |

| Veillonella | Disper | 3.85 | 4.69 | 0.225 | Obligate anaerobic | – | |

| Veillonella | Parvula | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.304 | Obligate anaerobic | Periodontitis, meningitis | |

| (b) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | RA at T0 | RA at T1 | p-value | oxygen demand | Relevant pathological conditions | |

| Acinetobacter | Rhizosphaerae | 1.16 | 0.69 | 0.108 | Aerobic | Nosocomial infections | |

| Actinobacillus | – | 0.70 | 0.01 | 0.005** | Facultative anaerobic | Endocarditis, periodontitis | |

| Actinomyces | – | 6.40 | 3.82 | 0.007** | Facultative anaerobic | Dentoalveolar abscess | |

| Corynebacterium | – | 2.86 | 1.80 | 0.041* | Aerobic | – | |

| Haemophilus | Parainfluenzae | 3.88 | 2.35 | 0.046* | Facultative anaerobic | Pneumonia | |

| Kingella | – | 1.23 | 0.67 | 0.039* | Aerobic | Endocarditis, septic arthritis | |

| Lautropia | Mirabillis | 3.33 | 0.72 | 0.001** | Facultative anaerobic | Cystic fibrosis | |

| Neisseria | – | 4.80 | 2.51 | 0.009** | Aerobic | – | |

| Rothia | Aeria | 0.95 | 0.24 | 0.407 | Facultative anaerobic | Endocarditis | |

| Rothia | Dentocariosa | 1.49 | 0.77 | 0.049* | Facultative anaerobic | Dental caries, endocarditis | |

| Streptococcus | – | 9.47 | 7.53 | 0.091 | Facultative anaerobic | – | |

| (c) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | RA at T0 | RA at T1 | RA at T2 | p-value | oxygen demand | Relevant pathological conditions |

| Atopobium | – | 0.28 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.046* | Facultative anaerobic | Periodontitis, vaginosis |

| Campylobacter | – | 1.08 | 1.85 | 2.32 | 0.008** | Facultative anaerobic | Periodontitis |

| Capnocytophaga | – | 2.16 | 2.73 | 3.63 | 0.245 | Facultative anaerobic | Periodontitis, animal bite wounds |

| Capnocytophaga | Ochracea | 0.38 | 0.53 | 1.17 | 0.002** | Facultative anaerobic | Periodontitis, dental caries |

| Fusobacterium | – | 3.25 | 4.02 | 7.04 | 0.001** | Obligate anaerobic | Periodontitis, colon cancer |

| Leptotrichia | – | 2.58 | 5.94 | 6.03 | 0.001** | Obligate anaerobic | Endocarditis |

| Paludibacter | – | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.67 | 0.001** | Obligate anaerobic | – |

| Prevotella | – | 4.94 | 5.56 | 7.57 | 0.032* | Obligate anaerobic | Periodontitis |

| Prevotella | Nigrescens | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.035* | Obligate anaerobic | Periodontitis, extraoral infections |

| Selenomonas | – | 0.26 | 1.34 | 2.47 | 0.001** | Obligate anaerobic | Periodontitis |

| Selenomonas | Noxia | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.004** | Obligate anaerobic | Periodontitis |

| Tannerella | - | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.023* | Obligate anaerobic | Periodontitis |

| (d) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | RA at T0 | RA at T1 | RA at T2 | p-value | Oxygen demand | Relevant pathological conditions |

| Granulicatella | – | 5.14 | 3.04 | 2.05 | 0.046* | Facultative anaerobic | Endocarditis |

| Neisseria | – | 9.16 | 7.58 | 3.62 | 0.054 | Aerobic | – |

| Neisseria | Subflava | 9.94 | 7.86 | 5.48 | 0.162 | aerobic | Meningitis |

| Rothia | Mucilaginosa | 4.40 | 2.37 | 2.25 | 0.832 | Facultative anaerobic | Endocarditis |

| Streptococcus | – | 15.97 | 12.86 | 11.73 | 0.220 | Facultative anaerobic | – |

(a) Increased bacteria in plaque with time and (b) decreased bacteria in plaque with time at genus or species level. Significant differences are indicated as bold letters and *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by Mann–Whitney U test. (c) Increased bacteria in saliva and (d) decreased bacteria in saliva with time at genus or species level. Significant differences are indicated as bold letters and *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by Kruskal–Wallis test.

Bacteria which decreased over time in supragingival plaque are listed in Table 1b. In accordance with the phylum level results, many genera belonging to Actinobacteria, such as Actinomyces, Corynebacterium, and Rothia, and Proteobacteria, such as Neisseria, Haemophilus, and Lautropia, were significantly lower at T1 than at T0. All bacteria that decreased with time were aerobes or facultative anaerobes. Streptococcus spp., including cariogenic group decreased from T0 (9.47%) to T1 (7.53%), although the difference was not significant.

Increased bacterial abundance in saliva over time is shown in Table 1c and reflect the results seen in plaque. Periodontal pathogens such as Prevotella, Porphyromonas, Capnocytophaga, Tannerella, Fusobacterium, Selenomonas, and Atopobium spp. significantly increased stepwise from T0 to T2. All the other bacteria that increased in saliva were facultative or obligate anaerobes.

Bacteria in saliva that decreased over time are shown in Table 1d. Neisseria, one of the core genera in saliva, decreased stepwise from T0 (9.16%) to T1 (7.58%) and T2 (3.62%) and Streptococcus decreased from T0 (15.97%) to T1 (12.86%) and T2 (11.73%), although these differences were not significant. All bacteria that decreased with time were aerobes or facultative anaerobes, consistent with the results in plaque.

Discussion

Numerous studies of the relationship between oral bacteria and orthodontic treatment have been performed via conventional methods, such as cultivation, and these studies have focused on specific types of bacteria. For example, increases in the incidence of dental caries and S. mutans bacterial counts were seen with fixed orthodontic appliances17,18. Similarly, placement of orthodontic appliances influenced clinical parameters and colonization of periodontal pathogenic bacteria such as P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, P. nigrescens, and F. nucleatum19–21. In this study, the number of detected OTUs slightly increased with time both in plaque and saliva, although there was no significant difference, suggesting that bacterial structure may have become more diverse after application of orthodontic appliances. The relative segregation in PCoA demonstrated discrepancies between bacterial structures at different time points, especially in plaque samples (Fig. 1a–c). There was no obvious difference between samples from upper and lower teeth.

Analysis of relative abundance at phylum level revealed more detail on bacterial distribution (Fig. 2a–c) such as the significant decrease in Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria in plaque. A wide variety of the normal flora found in the gut and oral cavity belong to the phylum Proteobacteria, while Actinobacteria represent important members of the environmental microbiome. The significant decrease of Actinobacteria after the placement of fixed orthodontic appliances have been reported previously16. Conversely, Bacteroidetes and Saccharibacteria (formally TM7), both anaerobes, significantly increased over time. Bacteroidetes are widely distributed in gut, oral cavity, and skin and include periodontal pathogenic bacteria, such as P. gingivalis and P. intermedia. Laboratory culture of Saccharibacteria has so far been impossible, here NGS analysis allowed us to detect this phylum. Saccharibacteria lives on the surface of its host bacterium. They affect oral microbial ecology by modulating the microbiome structure hierarchy and functionality through affecting the host’s physiology and the relative abundance of the host via direct killing22. Both in plaque and saliva samples, Saccharibacteria abundance significantly increased over time. The average age of the population sampled at T2 was different from that at T0 and T1, therefore we believe that this is likely also linked to the differences in microbiome, including Saccharibacteria abundance, observed at T2. Some reports suggest that Saccharibacteria increase with advancing age and have a role in initiating periodontitis23,24.

The genera Prevotella, Capnocytophaga, Atopobium, Selenomonas, and Campylobacter significantly increased with time in both plaque and saliva (Table 1a,c). The genus Prevotella, of the phylum Bacteroidetes, is comprised of obligate anaerobes and well-known pathogens of periodontal diseases25. Tanner et al. reported the genus Prevotella showed higher detection rate in plaque at high gingivitis group of orthodontic patients26. P. intermedia, one of the red-complex bacteria27, was observed to increase after the placement of an orthodontic appliance19 and then decrease after appliance removal in one study, but Choi et al. did not observe significant decrease following removal28. Guo et al. reported that P. intermedia showed significant increase not in molar area but in incisor area29. At species level, Prevotella melaninogentica and Prevotella nigrescens, which are also implicated in periodontitis, significantly increased in plaque and saliva, respectively (Table 1a,c). The genera Capnocytophaga, Campylobacter, Atopobium, and Selenomonas are facultative anaerobes. Interestingly, these genera are implicated in pathogenesis of periodontal diseases30–35. The genus Selenomonas were reported to increase after six and twelve weeks from the placement of orthodontic appliances in previous study16. The genus Porphyromonas (including P. gingivalis) which is obligate anaerobe and regarded as a major pathogen of periodontitis with highly proteolytic activity became higher in abundance during orthodontic treatment in plaque samples although there was no significant difference36. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, one of the pathogens of periodontitis, was reported to significantly increase three or six months after the placement of orthodontic appliances and remained higher level after removal37,38. These data suggest that the bacteria that significantly increased in relative abundance, in both plaque and saliva, were obligate and facultative anaerobes; notably most have been reported to be associated with periodontal diseases. No significant increase in the relative abundance of aerobes were detected after placement of appliances. These results strongly suggest that fixed orthodontic appliances alter the oral microbiome towards an anaerobic and periodontopathogenic state.

Abundance of organisms belonging to the genera Actinobacillus, Actinomyces, Corynebacterium, Kingella, and Neisseria and the species Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Lautropia mirabillis, and Rothia dentocariosa significantly decreased over time in plaque samples. Regarding Actinomyces, some studies reported that they significantly increase in plaque by orthodontic treatment. Koopman et al. found the genus Actinomyces increased with time, while Actinomyces naeslundii mainly increased after removal of the appliances16. Tanner et al. reported Actinomyces to be associated with gingivitis caused by orthodontic treatment26. These diverse results indicated that the genus Actinomyces showed variable behaviors by multiple factors such as host age on genus level. Neisseria has been reported to became higher in abundance twelve weeks after and became lower over time to the removal, and to be associated with low gingivitis group of orthodontic patients16,26. Most of these organisms that significantly decreased over time in plaque are aerobes or facultative anaerobes and are not associated with periodontal diseases. Commensal oral bacteria, such as Neisseria and Haemophilus spp., have previously been shown to decrease with time.

In our study, the genus Streptococcus also decreased over time both in plaque and saliva, although this difference was not statistically significant. Lucchese et al. reported in their systematic review study that the increase of S. mutans and Lactobacillus was influenced by the placement of orthodontic appliances39. We analyzed the relative abundance of bacteria in plaque and saliva by NGS, in contrast, their studies analyzed the whole volume of bacteria or bacterial DNA in plaque by colony counting and PCR. These methodological differences may account for the different conclusion.

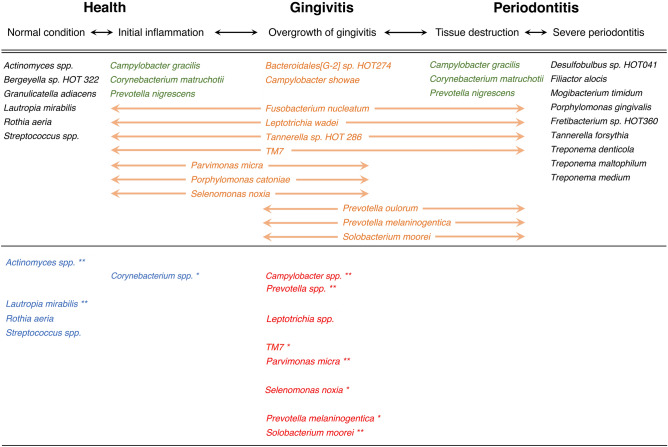

A recent study reported that the subgingival microbiome associated with gingival and periodontal inflammation is unique and distinct from the health-associated microbiome; proposing that the gingivitis-associated species are mediators of the transition in the health-to-periodontitis microbiome40,41. The species of Solobacterium moorei, Parvimonas micra, Selenomonas noxia, and P. melaninogentica which showed significant increase in supragingival plaque in our study (Fig. 4) are concordant with the gingivitis-associated bacteria of their report. The observed significant decrease in Actinomyces spp. and Rothia dentocariosa in supragingival plaque in this study is suggestive of a shift away from a healthy microbiome (Table 1b). These results suggest that orthodontic appliances are likely to change the gingival microbiome to a transitional stage between health and periodontitis.

Figure 4.

Comparison with previous findings on the gingival microbiome transition between health to periodontitis. The upper row shows the transitions of gingival condition. The middle row shows the model of temporal shifts in the gingival microbiome presented by Diaz et al. (2016). Gingivitis-associated species appear in orange text, core species (no change in relative abundance from health to periodontitis) appear in green text, and other bacteria appear in black text. The lower row shows the bacteria for which we observed changes in abundance in this study. The bacteria that increased from T0 to T1 appear in red text, and those that decreased appear in blue text. Significant differences are indicated as *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 by Mann–Whitney U test. T0 time point prior to placement of fixed orthodontic appliance, T1 time point approximately 6 months after the start of orthodontic treatment.

The genera Fusobacterium, Tennerella, Leptotrichia, and Paludibacter, all obligate anaerobes, significantly increased over time in saliva, although not in plaque (Table 1c). Fusobacterium and Tannerella are regarded as major pathogens in periodontal diseases; specifically, Fusobacterium nucleatum and Tannerella forsythia possess prominent pathogenic potential. F. nucleatum forms aggregates with other suspected pathogens in periodontal disease and, thus, acts as a bridge between early and late colonizers on the tooth surface42,43. T. forsythia is frequently isolated with P. gingivalis from cases of active, chronic periodontitis and co-aggregates with F. nucleatum, suggesting a process for enhancing colonization in the biofilm. The previous systematic review study conducted by PCR and culture method reported T. forsythia showed significant increase three months after the beginning of orthodontic treatment but the data was only focused on subgingival plaque29. The results of the study and our study including saliva sample strongly suggested the increase of the genus Tannerella in oral cavity after placement of orthodontic appliances. Zhao et al. reported that there were significant decrease of Prevotella abundance and overall microbial community structure did not change in saliva in spite of using NGS method as our study44. It is speculated that their contrast result to our finding of increased periodontal pathogens were due to the different types of orthodontic appliances; whereas we targeted fixed orthodontic appliances, they targeted removal orthodontic appliances.

In our study, the genus Granulicatella was significantly decreased in saliva, but there was a report conducted by PCR that Granulicatella elegans showed significantly higher detection rate in plaque at white-spot lesions group of orthodontic patients26. The reverse result may be caused by the differences of methodology and sampling site.

It is consistent both in plaque and saliva in terms of the increase of periodontal pathogens and anaerobes. The change in microbiome in supragingival plaque is likely to reflect a structural change, induced by placement of fixed orthodontic appliances on the tooth surfaces. Similar results were also observed with saliva samples because saliva passes through orthodontic appliances, both on the labial side and the lingual side and appliances were found to have no effect on unstimulated salivary flow rate45.

These changes suggest that obligate anaerobes and periodontopathogenic bacteria replaced aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria in the oral microbiome, especially in plaque, following placement of fixed orthodontic appliances. Sallum et al. and Yáñez-Vico et al. reported that periodontal pathogens can be significantly reduced after fixed orthodontic appliance removal46,47. This dysbiosis is expected to be reversed after removal and therefore a longer-term microbiome study taking into consideration the potential factors affecting this reversal may provide further insight.

In this study, we found the same tendency of the dynamics of Japanese oral microbiome not only in plaque but also in saliva by orthodontic treatment compared with previous studies although to varying degrees. In addition, we found that orthodontic appliances changed the plaque microbiome to the transitional condition between health to periodontitis by comparing with previous reports40,41. We used high-throughput sequencing focused on the16S rRNA gene, providing only taxonomical findings. However, the microbiome is understood to be affected by interspecies metabolic interactions2. Whole genome sequencing and/or metabolome analysis may provide a better understanding of the response of the oral microbiome following placement of fixed orthodontic appliances. We observed dynamic changes in the oral microbiome, with an increase in anaerobic pathogens, even though we did not see significant clinical manifestations of gingival status. Some of these anaerobes are known to be periodontopathogenic, but orthodontists normally do not monitor precise gingival status. Thus, we recommend that orthodontists should better monitor the results of periodontal examination from the beginning of treatment, even when patients are young and have no gingival problems. Evaluation of more subjects, a control group that did not receive orthodontic treatment and clinical parameters may help to verify if fixed orthodontic appliances pose a periodontal risk.

Conclusions

The oral microbiome measured in plaque and saliva changed during orthodontic treatment using fixed appliances. The shift represented an increase in anaerobes and periodontal pathogens and a decrease in commensal bacteria. Specifically, we propose that this shift, particularly in the supragingival microbiome, represents a transition between health and periodontitis.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of Hiroshima University Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan (No. 1645). Verbal informed consent was obtained from all the patients following provision of a full explanation of the study. This study included subjects under the age of 18, in which case informed consent was obtained from the parent or legal guardian. All samples were anonymized following collection.

Subjects and the types of orthodontic appliances

All subjects participating in this study were Japanese and underwent orthodontic treatment from July 2016 to April 2018 at the Department of Orthodontics, Hiroshima University Hospital (n = 71; Supplementary Table 1). The type of malocclusion of the subjects was anterior crowding. The inclusion criteria were: (1) a healthy systemic condition; (2) no receipt of antibiotics or other medicines before sampling; (3) no severe gingivitis, with a periodontal probing depth of less than 4 mm, or alveolar bone loss visible on panoramic X-ray; (4) no fixed restorations or removable dentures; (5) receipt of tooth brushing instruction (TBI) by dental hygienists before bracket placement and maintenance of proper oral hygiene. Although the oral hygiene status at the time of initial visit differed among patients, we repeated oral hygiene instruction until plaque control record (PCR) values fell under 20%. The standard edgewise system 0.018 inch slot brackets were directly bonded to the labial tooth surfaces and an arch wire composed of an alloy of nickel and titanium or cobalt and chrome were fixed to bracket slots using ligature wires.

Sample collection and storage

Three time points were evaluated: (T0) immediately before placement of fixed orthodontic appliances, (T1) 6 months after the beginning of orthodontic treatment, and (T2) immediately after removal of the appliances (40 months after placement on average, ranged from 20 to 62). Supragingival plaque samples were collected from upper and lower anterior teeth at T0 and T1. The area of tooth is above gingival margin at T0 and between gingival margin and cervical side of the brackets at T1. The sampling area was isolated with sterile cotton rolls and saliva removed by gentle air drying; supragingival plaque samples were then collected with a sterilized explorer. Unstimulated saliva samples were collected into a clean paper cup at T0, T1, and T2. To ensure standardization, the subjects were instructed to avoid eating, drinking, and tooth brushing at least 2 h before the sample taking. All the samples were collected at the beginning of the visits and pooled approximately into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube containing 0.5 mL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and stored immediately at − 80 °C until use48.

DNA extraction

Microbial DNA was extracted from supragingival plaque and saliva samples using a MasterPure Complete DNA and RNA Purification Kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions as previously performed by49, with minor modifications.

Library preparation and 16S rRNA gene sequencing

The V1-V2 hypervariable regions of 16S rRNA gene sequences were amplified by PCR using KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA) and primers from the Nextera XT Index Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA)50. Amplification was performed on a Veriti Thermal Cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). PCR products (approximately 450 bp) were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis, purified using Agencourt AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), and DNA concentrations were measured using a NanoDrop ND1000 spectrophotometer and Invitrogen Qubit 4.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Tag-indexed samples were diluted and pooled into a low DNA-binding tube in equal amounts from each sample. DNA concentration in the pooled samples was confirmed by qPCR, using KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR MasterMix (KAPA Biosystems). The library was applied to a MiSeq sequencing platform (Illumina). Nucleotide sequence data reported are available in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) Sequenced Read Archive under the accession number DRA010713.

Sequence data analysis and statistical analysis

Sequence data were analyzed with CLC Genomics Workbench ver.9 (QIAGEN, Venlo, Netherlands). Sequences were assigned to the same operative taxonomic units (OTUs) when within 97% similarity, in reference to the Greengenes database (https://greengenes.secondgenome.com). Additional statistical analysis such as Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis test were conducted using StatView 5.0 J (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparisons between two groups and Kruskal–Wallis test was used in multiple comparisons.

Ethic approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendment or comparable ethical standards.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the members of the Department of Orthodontics, Hiroshima University Hospital for kindly helping with sample collection.

Author contributions

I.K.: Contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. J.H.: Contributed to analysis and critically revised the manuscript. K.Ts.: Contributed to analysis and critically revised the manuscript. K.Ta.: Contributed to analysis and critically revised the manuscript. M.S.: Contributed to conception, design, acquisition, analysis, interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave their approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work supported by Grant-in-Aid Activity start-up No. 19K241210A from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-020-78971-2.

References

- 1.Kilian M, et al. The oral microbiome—An update for oral healthcare professionals. Br. Dent. J. 2016;221:657–666. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Human Microbiome Project C Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd-Price J, et al. Strains, functions and dynamics in the expanded human microbiome project. Nature. 2017;550:61–66. doi: 10.1038/nature23889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lang NP, Kiel RA, Anderhalden K. Clinical and microbiological effects of subgingival restorations with overhanging or clinically perfect margins. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1983;10:563–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1983.tb01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huser MC, Baehni PC, Lang R. Effects of orthodontic bands on microbiologic and clinical parameters. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial. Orthop. 1990;97:213–218. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(05)80054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paolantonio M, et al. Clinical and microbiological effects of different restorative materials on the periodontal tissues adjacent to subgingival class V restorations. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2004;31:200–207. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6979.2004.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basdra EK, Huber H, Komposch G. Fluoride released from orthodontic bonding agents alters the enamel surface and inhibits enamel demineralization in vitro. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 1996;109:466–472. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(96)70130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattingly JA, Sauer GJ, Yancey JM, Arnold RR. Enhancement of Streptococcus mutans colonization by direct bonded orthodontic appliances. J. Dent. Res. 1983;62:1209–1211. doi: 10.1177/00220345830620120601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenbloom RG, Tinanoff N. Salivary Streptococcus mutans levels in patients before, during, and after orthodontic treatment. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 1991;100:35–37. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(91)70046-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alp S, Baka ZM. Effects of probiotics on salivary Streptecoccus mutans and Lactobacillus levels in orthodontic patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;154:517–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mummolo S, et al. Salivary levels of Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacilli and other salivary indices in patients wearing clear aligners versus fixed orthodontic appliances: An observational study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0228798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anhoury P, et al. Microbial profile on metallic and ceramic bracket materials. Angle Orthod. 2002;72:338–343. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2002)072<0338:Mpomac>2.0.Co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SH, et al. Microbiologic changes in subgingival plaque before and during the early period of orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 2012;82:254–260. doi: 10.2319/030311-156.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghijselings E, et al. Long-term changes in microbiology and clinical periodontal variables after completion of fixed orthodontic appliances. Orthod. Craniofac Res. 2014;17:49–59. doi: 10.1111/ocr.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuczynski J, et al. Experimental and analytical tools for studying the human microbiome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;13:47–58. doi: 10.1038/nrg3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koopman JE, et al. The effect of fixed orthodontic appliances and fluoride mouthwash on the oral microbiome of adolescents—A randomized controlled clinical trial. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0137318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lundström F, Krasse B. Caries incidence in orthodontic patients with high levels of Streptococcus mutans. Eur. J. Orthod. 1987;9:117–121. doi: 10.1093/ejo/9.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jordan C, LeBlanc DJ. Influences of orthodontic appliances on oral populations of mutans streptococci. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2002;17:65–71. doi: 10.1046/j.0902-0055.2001.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naranjo AA, Trivino ML, Jaramillo A, Betancourth M, Botero JE. Changes in the subgingival microbiota and periodontal parameters before and 3 months after bracket placement. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130(275):e217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ristic M, Vlahovic Svabic M, Sasic M, Zelic O. Clinical and microbiological effects of fixed orthodontic appliances on periodontal tissues in adolescents. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2007;10:187–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2007.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goyal N, et al. Effects of amine fluoride and probiotic mouthwash on levels of Porphyromonas gingivalis in orthodontic patients: A randomized controlled trial. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2019;23:339–344. doi: 10.4103/jisp.jisp_551_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bor B, Bedree JK, Shi W, McLean JS, He X. Saccharibacteria (TM7) in the human oral microbiome. J. Dent. Res. 2019;98:500–509. doi: 10.1177/0022034519831671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crielaard W, et al. Exploring the oral microbiota of children at various developmental stages of their dentition in the relation to their oral health. BMC Med. Genom. 2011;4:22. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duran-Pinedo AE, et al. Community-wide transcriptome of the oral microbiome in subjects with and without periodontitis. ISME J. 2014;8:1659–1672. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nadkarni MA, et al. Pattern of distribution of Prevotella species/phylotypes associated with healthy gingiva and periodontal disease. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012;31:2989–2999. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1651-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanner AC, et al. White-spot lesions and gingivitis microbiotas in orthodontic patients. J. Dent. Res. 2012;91:853–858. doi: 10.1177/0022034512455031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holt SC, Ebersole JL. Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia: The "red complex", a prototype polybacterial pathogenic consortium in periodontitis. Periodontology. 2005;2000(38):72–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi DS, et al. Microbiologic changes in subgingival plaque after removal of fixed orthodontic appliances. Angle Orthod. 2009;79:1149–1155. doi: 10.2319/111808-593r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo R, Lin Y, Zheng Y, Li W. The microbial changes in subgingival plaques of orthodontic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17:90. doi: 10.1186/s12903-017-0378-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kapke PA, Brown AT, Lillich TT. Carbon dioxide metabolism by Capnocytophaga ochracea: Identification, characterization, and regulation of a phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. Infect. Immun. 1980;27:756–766. doi: 10.1128/IAI.27.3.756-766.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ihara H, et al. Detection of Campylobacter rectus in periodontitis sites by monoclonal antibodies. J. Periodontal Res. 2003;38:64–72. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2003.01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar PS, et al. New bacterial species associated with chronic periodontitis. J. Dent. Res. 2003;82:338–344. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonçalves LF, et al. Levels of Selenomonas species in generalized aggressive periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 2012;47:711–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2012.01485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peterson SN, et al. The dental plaque microbiome in health and disease. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e58487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaakoush NO, Castano-Rodriguez N, Mitchell HM, Man SM. Global epidemiology of campylobacter infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015;28:687–720. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mysak J, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis: Major periodontopathic pathogen overview. J. Immunol. Res. 2014;2014:476068. doi: 10.1155/2014/476068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papageorgiou SN, Xavier GM, Cobourne MT, Eliades T. Effect of orthodontic treatment on the subgingival microbiota: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2018;21:175–185. doi: 10.1111/ocr.12237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan S, et al. Profiling of subgingival plaque biofilm microbiota in adolescents after completion of orthodontic therapy. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0171550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lucchese A, Bondemark L, Marcolina M, Manuelli M. Changes in oral microbiota due to orthodontic appliances: A systematic review. J. Oral Microbiol. 2018;10:1476645. doi: 10.1080/20002297.2018.1476645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong BY, et al. Microbiome profiles in periodontitis in relation to host and disease characteristics. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0127077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diaz PI, Hoare A, Hong BY. Subgingival microbiome shifts and community dynamics in periodontal diseases. J. California Dent. Assoc. 2016;44:421–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kolenbrander PE, London J. Adhere today, here tomorrow: Oral bacterial adherence. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:3247–3252. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3247-3252.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bolstad AI, Jensen HB, Bakken V. Taxonomy, biology, and periodontal aspects of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1996;9:55–71. doi: 10.1128/CMR.9.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao R, et al. The dynamics of the oral microbiome and oral health among patients receiving clear aligner orthodontic treatment. Oral Dis. 2020;26:473–483. doi: 10.1111/odi.13175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lara-Carrillo E, Montiel-Bastida NM, Sanchez-Perez L, Alanis-Tavira J. Effect of orthodontic treatment on saliva, plaque and the levels of Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus. Med. Oral. Patol. Oral. Cir. Bucal. 2010;15:e924–929. doi: 10.4317/medoral.15.e924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sallum EJ, et al. Clinical and microbiologic changes after removal of orthodontic appliances. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2004;126:363–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yáñez-Vico RM, et al. Short-term effect of removal of fixed orthodontic appliances on gingival health and subgingival microbiota: A prospective cohort study. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2015;73:496–502. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2014.993701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morita H, et al. An improved DNA isolation method for metagenomic analysis of the microbial flora of the human intestine. Microbes Environ. 2007;22:214–222. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.22.214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Biesbroek G, et al. Deep sequencing analyses of low density microbial communities: Working at the boundary of accurate microbiota detection. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e32942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim SW, et al. Robustness of gut microbiota of healthy adults in response to probiotic intervention revealed by high-throughput pyrosequencing. DNA Res. 2013;20:241–253. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dst006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.