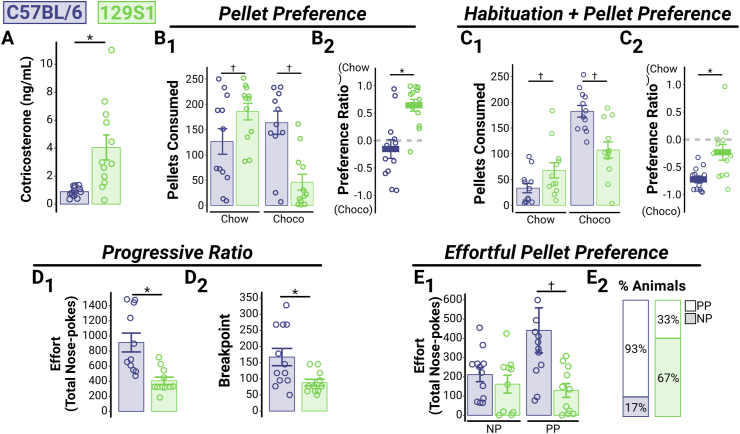

Fig. 3.

129S1 mice exhibit higher CORT levels and reduced reward-seeking, even in a lower-stress environment.

(A) CORT levels, measured at the conclusion of operant behavioral tasks, were higher in 129S1 mice (n = 12 [6M, 6F]) compared to C57BL/6 mice (n = 12 [5M, 7F]) (together, comprising Cohort 3), even in a home-cage environment (p = 0.002). (B) In the same cohort (Cohort 3), evaluation of pellet preference was carried out using standard chow and sweetened chocolate pellets; 129S1 mice consumed more chow pellets (B1 “Chow”, p = 0.049) and fewer chocolate pellets (B1 “Choco”, p = 0.0003) than C57BL/6 mice over a 24-h period (average of three consecutive days). Further, preference ratios calculated for individual animals showed that 129S1 mice exhibited a significantly stronger preference for the chow pellets than the C57BL/6 mice (B2, p = 0.001). The dashed line indicates an equal number of chow and chocolate pellets eaten (preference ratio of 0). (C) To account for the possibility of neophobia to the chocolate pellets, a separate cohort (Cohort 4) of C57BL/6 mice (n = 12 [7M, 5F]) and 129S1 mice (n = 12 [6M, 6F]) received three days of habituation to both pellet types prior to beginning the pellet preference experiment. Even after habituation, 129S1 mice still consumed more chow pellets (C1 “Chow”, p = 0.0499) and fewer chocolate pellets (C1 “Choco”, p = 0.0002) than the C57BL/6 mice. While the relative preference for chocolate pellets increased in both strains (compare to B1), C57BL/6 mice still exhibited a significantly stronger preference ratio for chocolate pellets than did the 129S1 mice (C2, p = 0.004). The dashed line indicates an equal number of chow and chocolate pellets eaten (preference ratio of 0). (D) Motivation to work for a food reward was assessed using a progressive ratio reinforcement schedule (in Cohort 3 mice). 129S1 mice expended less effort (fewer total nose-pokes; D1, p = 0.001) and had a lower breakpoint (D2, p = 0.014) than did C57BL/6 mice. (E) In a separate cohort (Cohort 5; C57BL/6: n = 12 [6M, 6F]; 129S1: n = 10 [6M, 4F]), we assessed the relative valuation of food rewards by comparing performance when a high-cost/high-reward (progressive ratio and preferred pellet [PP]) and a lower-cost/lower-reward (fixed-ratio 5 and non-preferred pellet [NP]) option were both available. 129S1 mice expended equal effort for the lower-cost/lower-reward option (E1 “NP”, p = 0.6095), but significantly less effort for the high-cost/high-reward option (E1 “PP”, p = 0.0037) compared to the C57BL/6 mice. Additionally, we found that the majority of 129S1 mice spent most of their effort on the lower-cost/lower-reward choice while only a small fraction of C57BL/6 mice did the same (E2). For all panels, asterisks indicate significant main effects and crosses indicate significant post-hoc tests.