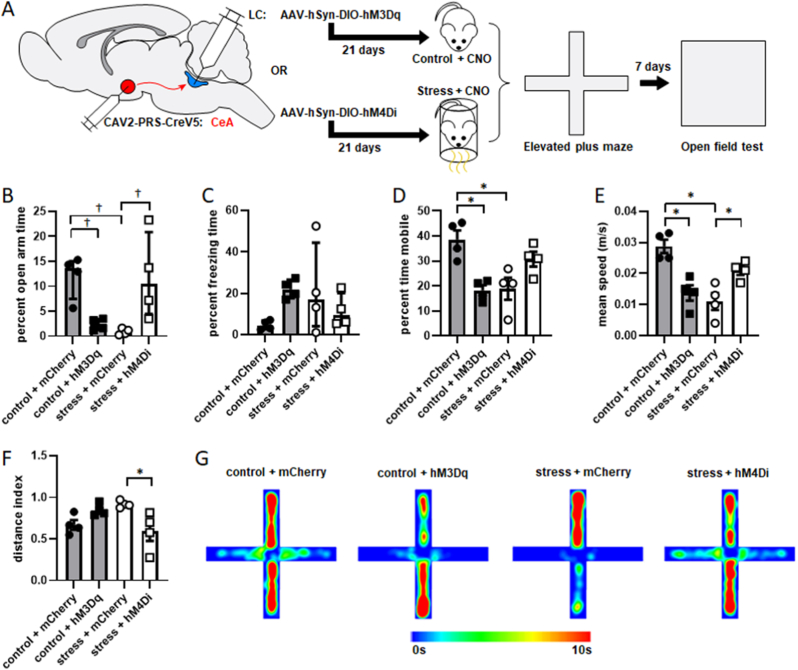

Fig. 4.

LC→CeA neurons are acutely necessary and sufficient for anxiety-like behavior in the EPM. The experimental timeline is shown in A. Animals underwent a surgical procedure to inject CAV2-PRS-CreV5 bilaterally in CeA and AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM3Dq-mCherry, AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry, or AAV-hSyn-DIO-mCherry bilaterally in LC. Three weeks later, all rats received an IP injection of 2.5 mg/kg CNO. Half an hour later, rats expressing hM3Dq underwent control conditions (n = 4), and rats expressing hM4Di underwent stressor exposure (n = 4). Rats expressing mCherry without a DREADD as a control were exposed to either control (n = 4) or stress (n = 4). Behavior was then assessed in the EPM and animals were returned to their home cages. One week later, behavior was assessed in the OFT. Rats were then perfused for verification of injection sites and transgene expression. Both percent open arm time and percent time freezing in the EPM were square root transformed to satisfy requirements for parametric statistical testing. (B) Rats whose LC→CeA cells expressed hM3Dq and were activated prior to control conditions spent a significantly smaller percentage of time in the open arms than control rats that expressed mCherry in LC→CeA cells. Rats whose LC→CeA cells expressed hM4Di and were inhibited prior to stressor exposure spent a significantly greater percentage of time in the open arms than stressed rats whose LC→CeA cells expressed mCherry. Stressor-exposed rats expressing mCherry in LC→CeA cells also spent significantly less time in time in the open arms than control rats expressing mCherry in LC→CeA cells (shown as median with interquartile range). (C) Freezing behavior was not significantly affected by manipulation of the LC→CeA projection (shown as median with interquartile range). Rats that had their LC→CeA projection activated prior to control conditions spent a significantly smaller percentage of time mobile than rats whose LC→CeA cells were unmanipulated. Control rats whose LC→CeA cells were unmanipulated also spent a significantly greater percentage of time mobile than stressor-exposed rats whose LC→CeA cells were unmanipulated (D). Activation of the LC→CeA projection prior to control conditions also led to significantly lower speeds in the EPM as compared to rats whose LC→CeA cells were not activated prior to control. Inhibition of LC→CeA cells prior to stressor exposure caused a significant increase in average speed relative to stressed rats whose LC→CeA cells were not inhibited. In rats whose LC→CeA cells were not manipulated, stressor exposure significantly decreased average speed relative to controls (E). To determine if these effects simply reflected altered motor function rather than alterations in anxiety-like behavior, a distance index was calculated as the amount of distance traveled in the closed arms minus the distance traveled in the open arms divided by total distance traveled. A value of 1 would indicate all travel was in closed arms, while −1 would indicate all travel was in open arms. Inhibition of LC→CeA projection cells prior to stressor exposure led to a significant decrease in distance index relative to stressed rats whose LC→CeA cells were unmanipulated, suggesting increased travel in the open arms relative to the closed arms (F). Mean heat maps for activity in the EPM are shown in G. *: p < 0.05. †: p < 0.05 after square root transformation.