Abstract

Yeasts are used to produce a myriad of value-added compounds. Engineering yeasts into cost-efficient cell factories is greatly facilitated by the availability of genome editing tools. While traditional engineering techniques such as homologous recombination-based gene knockout and pathway integration continues to be widely used, novel genome editing systems including multiplexed approaches, bacteriophage integrases, CRISPR-Cas systems and base editors are emerging as more powerful toolsets to accomplish rapid genome scale engineering and phenotype screening. In this review, we summarized the techniques which have been successfully implemented in model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as well as non-conventional yeast species. The mechanisms and applications of various genome engineering systems are discussed and general guidelines to expand genome editing systems from S. cerevisiae to other yeast species are also highlighted.

Keywords: Gene Editing, Cre-lox, Serine integrase, TALENs, CRISPR-Cas9, CRISPR-Cas12a, Non-conventional yeast

Introduction

In modern biotechnology, yeast have been extensively studied due to advantageous traits including well established genetics, fast growth rate, simple nutrient requirements, have wider growth conditions compared to bacteria, lack of phage infectivity and many have been granted generally regarded as safe (GRAS) status by the US Food & Drug Administration [1]. Engineered yeast cell factories have been widely leveraged to produce recombinant proteins with post-translational modifications [2], pharmaceuticals [3], biofuels [4], fine chemicals [5,6] and other value-added products [7]. The development of industrially relevant yeast strains to meet the increasing demands of chemical production using cheap feedstocks is driven by the capability to modify yeast genome. Altering the carbon flux by tuning the expression level of metabolic pathway genes generally requires overexpression, deletion or down-regulation of specific genes.

Although the term “genome editing” has been widely used, its definition remains to be clarified. In this review, we define genome editing as site-specific genome modification, inclusive of gene knockout, integration and intentional point mutations. While traditional genome engineering techniques such as homologous recombination (HR) could efficiently achieve genomic modifications in baker′s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae due to its dominant HR mechanism, this technique is much less efficient in other yeast species including Yarrowia lipolytica and Pichia pastoris where non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) is the major mechanism [8,9]. The traditional iterative genome engineering approach, such as HR-based integration of cassettes, is hindered by the low integration efficiency resulting from low frequency of double-stranded DNA breaks, which significantly slows the design-build-test-learn (DBTL) cycle. To accelerate the engineering process across all yeasts, technologies such as the rapid-evolving clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) mediated genome editing have emerged as a powerful toolbox in yeast metabolic engineering. While there are excellent reviews of yeast genome engineering [10-13], the rapidly evolving nature of the field warrants frequent updating. In this review, we will discuss various genome editing techniques (Table 1), highlight the recent advances of genome editing tools across biotechnologically important yeast species and give our perspectives on the future directions of yeast genome editing, with emphasis on how more advanced genome engineering tools might be adapted to non-conventional and non-model yeast.

Table 1.

Comparison of genome editing technologies in yeast

| Technology | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ | Non-homologous end joining | Random integration; Easy to implement | Variable expression level; Low efficiency for large fragments |

| Cre-loxP | Cre mediated site-specific recombination | High efficiency; Easy to implement | Needs marker removal, loxP site left on genome. Lack of endogenous sites. |

| Serine integrase | Serine integrase mediated site-specific recombination | High efficiency; marker less integration; large integration capacity | Lack of endogenous sites for integration |

| TALEN | TALE nuclease mediated DSB | High specificity; programmable, multiplexing | Complex assembly of DNA construct |

| CRISPR-Cas | RNA guided nuclease mediated DSB | High efficiency, programmable, multiplexing, marker less integration | Possible off-target |

| Base editing | Deaminase fusion to nuclease deficient Cas9 mediated base conversion | No DSB; Programmable; Multiplexing | Often low efficiency; off-target effects underexplored. |

Bacteriophage recombinases

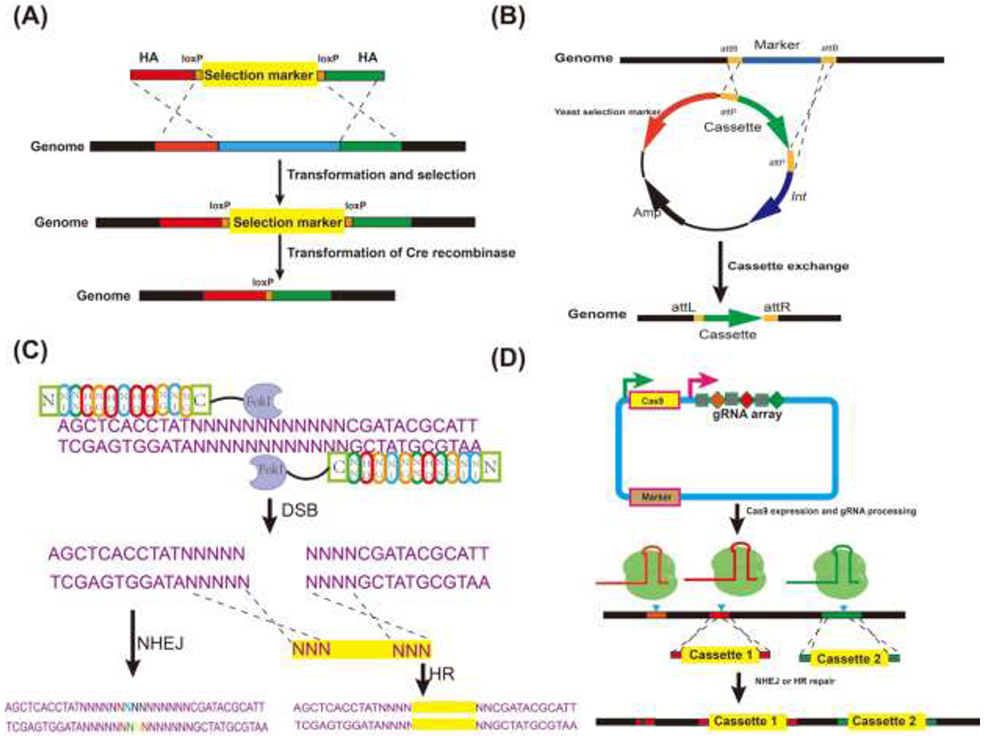

Bacteriophage integrases were adapted for genetic engineering across species due to its high efficiency and specificity. Cre recombinase belongs to the tyrosine integrase family and is derived from the bacteriophage P1. The Cre-loxP system consists of the Cre recombinase and its substrate the loxP site. Efficient recombination between two loxP sites could lead to deletion, inversion and translocation depending on the orientation of loxP sites (Figure 1A). An integration cassette with a selection marker flanked by loxP sites can be used for gene knock-out and knock-in. For gene knockout process, the curing of the selection marker can be achieved by overexpression of the Cre recombinase. This system has been successfully adapted for metabolic engineering in S. cerevisiae [14,15], Y. lipolytica [16,17], K. marxianus [18] and O. polymorpha [19]. Cre-loxP system was also implemented in the international synthetic yeast genome project, Sc2.0 to allow inducible genome rearrangement, presenting a powerful tool in synthetic biology [20]. One drawback of the Cre-loxP system is the loxP scar left on the genome after marker cure, which could lead to unintended genome alterations and gene losses through recombination between scars [21]. Due to the relatively low knock-in efficiency and lack of orthogonal Cre recombinases, the Cre-loxP system is generally used for single gene knockout.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of yeast genome editing techniques.

(A) HR and Cre-loxP system. Integration cassette with selection marker flanked by loxP sites is integrated into genome via HR. Selection marker is cured by expression of Cre recombinase. (B) Serine integrase mediated marker less integration. Plasmid containing serine integrase and integration cassette flanked by attP sites of serine integrase is transformed into yeast installed with attB sites of serine integrase. Expression of serine integrase could mediate recombination between attB and attP sites to integrase the cassette. (C) TALEN mediated genome engineering in yeast. TALEN consists of a DNA binding domain and a FokI nuclease domain. DSB is repaired by NHEJ to result in indel mutations or HR to achieve knock-in. (D) Multiplexed genome editing using CRISPR-Cas. Delivery of Cas effector and gRNA array can be achieved on a single plasmid. gRNA array is separated by a spacer such as tRNA to facilitate the gRNA processing. Simultaneous gene knockout and cassette knock-in is achieved.

Serine integrase is another type of phage integrase and has been developed to engineer certain non-model bacteria [22,23] which lack genetic tools. Serine integrase catalyzes the site-specific recombination between the attB and attP sites. Gene expression cassettes or whole plasmid can be integrated into host genome harboring the attachment sites via cassette exchange or single crossover, respectively (Figure 1B). Moreover, serine integrase mediated in vitro recombination can be employed for rapid pathway assembly to accelerate the cloning process [24]. The high efficiency and capacity of this system makes it an attractive tool for the genome engineering of yeast species. Xu et al., investigated ten serine integrases in S. cerevisiae and identified a few highly active candidates suitable for genome engineering including ϕBT1, R4, BXB1 and ϕC31 [25]. The efficiency of integrase mediated recombination was ten times higher than that of HR while avoiding the repetitive scar sequences caused by Cre-lox. This study could be transferred to other yeast species to develop efficient genetic engineering tools.

TALENs

Transcription activator like effectors (TALEs) were first discovered in plant pathogen which exploits TALEs to infect its host. TALE Nuclease (TALEN) are TALEs with nucleases fused forming an artificial sequence-specific nuclease consisting of DNA binding domain of TALEs and the catalytic domain of FokI endonuclease [26,27]. The DNA binding domain of TALENs consist of tandem repeats of 33 to 35 amino acids. Each repeat contains variable di-residues (RVDs) to determine the recognition of a single nucleotide [28] (Figure 1C). The modularity of TALENs allows assembly of construct to target essentially any DNA sequence. Efficient single gene knockout of URA3, ADE2 and LYS2 based on NHEJ or homology directed repair (HDR) was reported in S. cerevisiae using a modular assembly strategy [29]. TALENs mediated gene knockout and site-directed mutagenesis has been successfully implemented to enhance production of fatty acid in S. cerevisiae [30] and Y. lipolytica [31]. Zhang et al. designed a strategy based on TALENs assisted multiplex editing (TAME) to accelerate the evolution of S. cerevisiae genome [32]. In this work, targeting sequences for the TATA box and the GC box across the S. cerevisiae genome were identified using in silico scripts. TALENs were expressed under the inducible GAL promoter using mCherry as a reporter gene. Iterative induction and selection could identify mutants with the highest fluorescence. This strategy was then applied to evolve a yeast strain with faster glucose consumption and higher ethanol titer. The TAME screening was also leveraged to improve the stress tolerance to hyperosmotic pressure and high temperature in an industrial strain of S. cerevisiae [33]. TALENs have been largely used in S. cerevisiae despite its high efficiency for genome editing. Assembly of large repeats in TALENs is challenging which could limit its application in other yeast species especially when other genome editing systems such as CRISPR-Cas are available.

CRISPR based technologies

CRISPR-Cas genome editing of S. cerevisiae

The type II CRISPR-Cas9 genome editor derived from the bacterial immune system has revolutionized biotechnology due to its high specificity and versatility. CRISPR-Cas9 systems cleave target DNA by the nucleoprotein complex formed between the Cas9 nuclease effector and an engineered single guide RNA (sgRNA) that cause double strand break (DSB) 3 bp upstream of the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence [34]. DSB are mainly repaired by NHEJ resulting in insertion or deletion (indel) mutations or by HDR (Figure 1D). The application of this system in model yeast S. cerevisiae was first described by DiCarlo et al [35]. Expression of codon optimized Cas9 gene from Streptococcus pyogenes and guide RNA were delivered using two vectors. Toxicity of the CRISPR-Cas9 system was also observed when Cas9 and gRNA were simultaneously expressed. It was also found that co-transformation of a donor DNA with gRNA on a transient expression cassette or plasmid could significantly boost HR at the cutting site. The efficiency of single gene targeting in S. cerevisiae was generally high despite optimization of the design of gRNA is required. Currently, various web-based gRNA design algorithms were available to help minimize off-target effects [11]. Multiplexed genome editing is a desirable feature of the CRISPR-Cas system. Various strategies for delivery of multiple gRNA have been described. Bao et al. described the HI-CRISPR system where a Cas9 mutant with improved activity, crRNA array and tracrRNA were expressed under different promoters on a high copy plasmid [36]. Pre-crRNA was processed into single spacer and formed functional complex with tracrRNA and SpCas9 protein. The efficiency of a triple deletion reached 87% using this system after four days of outgrowth in selective media. Mans and coworkers reported the introduction of up to six modifications to the S. cerevisiae genome including integration of multi-gene pathway, gene knock-out and site-directed mutagenesis in one transformation step [37]. In this work, up to two gRNAs which were designed by a web-based tool were carried on plasmids with different selection markers. It was found that six-gene deletion efficiency reached 65%. Horwitz et al. reported a technique for multiplexed gene deletion and pathway integration by using linearized plasmid bearing Cas9 and gRNA cassettes sharing homology with linearized plasmid in S. cerevisiae [38]. It was reported that the efficiency of triple deletion reached 64% and a 24-kb pathway for the biosynthesis of muconic acid could be integrated into three loci in one step transformation. Although multiple gRNA can be separately expressed, the cloning and sub-cloning process can be time-consuming. Fusion of self-cleaving hepatitis delta virus (HDV) ribozyme to gRNA to facilitate gRNA processing was able to achieve 86% and 43% targeting efficiency for duplex genome editing in haploid and diploid strain of S. cerevisiae, respectively [39]. Zhang et al. described a rapid multiplexed genome editing strategy by using an array of gRNA spaced by transfer RNA of glycine (tRNAGly) [40]. The gRNA array was assembled using golden gate assembly, expressed under the SNR52 promoter and directly transformed into S. cerevisiae. It was reported that the disruption efficiency of eight genes reached 87%, which is the highest number of simultaneous gene deletions to date in S. cerevisiae. This strategy could be a valuable tool for rapid genome engineering of the baker’s yeast.

Cas12a or Cpf1 was another CRISPR effector, belonging to the type V CRISPR system. Compared with Cas9, Cas12a recognizes distinct T-rich PAM sequence (TTTN) and is able to process the premature crRNA array, which is particularly suitable for multiplexed genome editing [41]. The CRISPR-Cas12a/Cpf1 system was also investigated for genome editing in S. cerevisiae. Verwaal et al. explored the functionality of three Cpf1 effectors: Acidaminococcus spp. Cpf1 (AsCpf1), Lachnospiraceae bacterium Cpf1 (LbCpf1) and Francisella novicida Cpf1 (FnCpf1) [42]. The Cpf1 effectors were evaluated by targeted genomic integration of the three gene pathway of carotenoid biosynthesis and yellow fluorescent protein (YFP). It was found that LbCpf1 and FnCpf1 could reach targeting efficiency comparable to that of SpCas9. Multiplexed genomic integration of the carotenoid pathway into three non-coding regions was also achieved using LbCpf1 and a single crRNA array expressed by SNR52 promoter. The efficiency of multiplexed editing was 91%. Li et al. developed a self-cloning CRISPR-Cpf1 system for genome editing and strain building in S. cerevisiae [43]. Single crRNA or crRNA array generated by PCR was co-transformed with a low copy plasmid bearing Cpf1 and a palindromic crRNA sequence. Complex of Cpf1 and palindromic crRNA will self-cleave the plasmid and allow the cloning of target crRNA via in vivo recombination. It was reported that efficiency of single and triplex genomic integration reached 80% and 32% using this self-cloning system.

Multiplexed automated genome scale engineering (MAGE) represents a powerful advance in yeast genome editing. The first report of yeast oligo genome engineering (YOGE) demonstrated that recombineering of yeast was possible but only about 1% efficient [44]. Soon after, eukaryotic MAGE (eMAGE) was reported. It relies on annealing of synthetic oligos to the lagging strand during DNA replication, and therefore, relies on the proximity the target site to the replication fork [45]. CRISPR-Cas9 was used to create double-strand DNA breaks at the δ-retrotransposon sites scattered throughout the genome, which facilitated substantially improved integration of large genetic circuits [46]. Thousands of specific single nucleotide genome edits were achieved using CRISPR-Cas9-and homology-directed-repeat (CHAnGE), where a library of homology repair templates encoding specific genomic changes is recombined at a double-stranded break caused by the CRISPR-Cas9. This genome-scale effort was demonstrated by selecting for gene disruptions causing tolerance to growth inhibitors [47]. Error prone PCR libraries of carotenoid pathway enzymes were introduced into the native enzyme genomic loci by CRISPR-Cas9 mediated double strand break and homology directed repair. This method of Cas9-mediated protein evolution reaction (CasPER) resulted in an 11-fold improvement in isoprenoid production and demonstrating efficient enzyme directed evolution in a genomic context [48].

Genome editing in non-conventional yeasts using CRISPR-Cas

In nearly all the aforementioned works, the high efficiency of homology directed repair in S. cerevisiae was utilized. Most non-conventional yeasts are highly inefficient at homology directed repair compared with non-homologous end-joining. As a result, different approaches for genome editing are needed.

Yarrowia lipolytica

The oleaginous yeast Y. lipolytica has been extensively studied in recent years due to its capability to accumulate large amounts of lipids [49-51], and ability to grow on a wide range of substrates including xylose [52], acetic acid, fatty acids and alkanes [53]. Y. lipolytica has been engineered to produce value-added chemicals including β-carotene [54,55], polyketide [56,57], polyunsaturated fatty acids [5] and terpenoids [58,59]. The CRISPR-Cas system has been adapted to facilitate metabolic engineering in Y. lipolytica [60]. Despite the high efficiency of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in S. cerevisiae implementing this system in Y. lipolytica required non-obvious suitable promoters for the expression of gRNA. Schwartz el al. reported genome editing of Y. lipolytica using CRISPR-Cas9 for the first time [61]. The authors optimized the expression of gRNA using both RNA polymerase type II promoter (TEF promoter) and several predicted RNA polymerase type III promoters. It was found that a synthetic SCR1′-tRNAGly promoter could achieve the highest editing efficiency (92%) of PEX10 gene after outgrowth. Quantitative PCR analysis of the abundance of gRNA under different promoters revealed that the level of gRNA transcript under SCR1′-tRNAGly promoter was high but not the highest, indicating that the editing efficiency may not be positively correlated with transcript level. This work also highlights outgrowth in selective media can significantly boost the gene editing efficiency. Using this CRISPR system, Schwartz et al. also identified 5 out of 17 loci for efficient markerless genomic integration in NHEJ capable cells [62]. Stable integration can be achieved by transforming the CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid and the respective donor plasmid harbouring the desired gene cassette. Holkenbrink et al. developed a streamlined toolbox EasyCloneYALI which consists of a set of vectors for efficient genome integration and gene knock-out in Y. lipolytica via CRISPR-Cas9 in NHEJ deficient KU70 knockouts [63]. It was reported that up to 80% of integration efficiency, 90% efficiency of single gene knock-out and 66% efficiency of double knock-out can be achieved.

To establish a multiplexed genome editing strategy for Y. lipolytica, Gao et al. constructed a single plasmid to overexpress Cas9 and multiple gRNA under the TEF intron promoter [64]. Self-cleaving hammer head ribozyme (HHR) and HDV were added to flank the gRNA sequence to facilitate the release of mature gRNA. It was observed that expression of two gRNA on a single plasmid outperforms that on two separate plasmids in terms of duplexed editing efficiency. The efficiency for double knock-out and triple knock-out was 36.7% and 19.3%, respectively. It should also be noted that outgrowth was performed to achieve the high editing efficiency.

In a recent study, the CRISPR-Cas12a system was adopted for efficient and multiplexed genome editing in Y. lipolytica [65]. Yang and coworkers implemented this system by overexpressing the AsCas12a gene and gRNA under various promoters. It was observed that the highest editing efficiency (93.3%) for targeting CAN1 was achieved under the TEF intron promoter without adding any HHR or HDV, which indicates that TEF intron promoter could be a promising candidate for the expression of self-cleaving crRNA. Duplexed and triplexed genome editing was also achieved by overexpressing multiple crRNA on a single plasmid, reaching an efficiency of 83.3% and 41.5%, respectively. A second study of Cas12a activity in Y. lipolytica focused on gRNA engineering, demonstrating high efficiency disruptions using 23-25 bp gRNAs that could be multiplexed with truncated gRNAs that caused robust gene repression [66].

CRISPR-Cas9 was leveraged to study functional genomics of Y. lipolytica by constructing a genome-wide gRNA library to target 7845 coding sequences (CDS) [67]. Six gRNAs were designed to target each CDS. Three Y. lipolytica strains: Po1f, Po1f harboring Cas9 and Po1fΔ ku70 harboring Cas9 were used to validate the gRNA library. Fitness score (FS) and cutting score (CS) was defined to evaluate the essentiality and cutting efficiency of each gRNA by measuring the abundance of gRNA in strain Po1f-Cas9 and Po1fΔku70-Cas9 relative to that in control Po1f strain. CS values were used to identify efficient gRNAs and exclude inactive gRNAs from essential gene determination and to obtain a validated library. A total of 1377 CDSs were identified as essential based on the validated library. This library was also a useful tool to facilitate screening of growth and non-growth associated phenotypes such as canavanine resistance and lipid content screening.

Rhodosporidium toruloides

Another oleaginous yeast species R. toruloides can accumulate high content of lipids and carotenoids. It can also covert lignocellulose hydrolysate into valuable compounds [68], making this yeast an attractive platform to produce acetyl-CoA derived chemicals using renewable feedstocks. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing of R. toruloides was achieved by integrating a cassette to express Cas9 under GAP promoter and gRNA under S. cerevisiae SNR52 promoter [69]. Targeting efficiency of URA3 was estimated to be 0.001%. Further optimization including gRNA target sequence and the use of tRNAPhe promoter improved editing efficiency of URA3 to 0.62%. Duplexed editing of URA3 and CAR2 was achieved by expressing two gRNAs for each target gene in an array spaced by tRNAGly, with efficiency of 30%. In another study, codon optimized Cas9 of Staphylococcus aureus was first integrated into the R. toruloides genome. Two U6 promoters were identified to drive the expression of gRNA. It was observed that editing efficiency of CRT1, CAR2 and CLYBL achieved 66.7%, 75% and 75%, respectively. The HR mediated knockout of CRT1 was also explored with an efficiency of 8%, likely due to the NHEJ dominant repair mechanism [70]. Schultz et al. optimized the expression of SpCas9 under various Pol II promoters and gRNA using five different promoter constructs in R. toruloides [71]. The expression of SpCas9 driven by PGK1 promoter and gRNA by a 5S-tRNAGly fusion promoter led to the highest editing efficiency of CRTYB (99%), CRTI (96%) and LEU2 (88%). Duplexed editing of CRTYB and LEU2 was also achieved with a double knockout efficiency of 78%. This work highlighted a strategy to optimize promoters for the expression of gRNA in non-conventional yeasts.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe

The fission yeast S. pombe is gaining research interests one of the model organisms for genetics and cellular biology [72]. To unlock the research and industrial potential of this yeast, genetic engineering tools based on CRISPR-Cas9 has been developed. Jacob et al. described a strategy by placing gRNA between the rrk1 promoter and a cleavable leader sequence and HHR. Transformation of gRNA construct and Cas9 on two plasmids to target ADE6 led to efficient disruption of this gene (85%-98%) when a donor cassette was co-transformed [73]. The same strategy was implemented in S. pombe by using a fluoride counter-selectable marker [74]. Targeting efficiency of 33% was obtained for PIL1. Zhang et al. described a cloning-free procedure by exploiting the gap repair mechanism in S. pombe. High knock-in efficiency (84%) was achieved by co-transforming a 90 bp donor oligo [75]. Hayashi and coworker described genome editing in S. pombe using microhomology-mediated end-joining (MMEJ) [76]. It was found that co-transformation of Cas9/gRNA plasmid with short oligos (15bp, 20 bp or 25 bp) lead to point mutation (W104A) of swi6 gene with efficiency of 10% to 100%. The effectiveness of this strategy was also validated by introducing point mutation (S604A) to the mrc1 gene (encoding mediator of replication checkpoint protein 1) with 70% knock-in efficiency. In a recent study, CRISP-Cas12a was implemented in S. pombe by expressing FnCas12a under adh1 promoter and crRNA under rrk1 promoter in a single plasmid [77]. The targeting efficiency of ADE6 was 25-50% (10-30% for LEU1, HIS3 and LYS9) using a HR donor DNA with 800 bp homology to the ends of DSB. The authors also investigated other endogenous pol II promoters to express crRNA and found that the fba1 promoter can result in 30% higher editing efficiency of ADE6. Duplexed (ADE6 and LEU1) and triplex (ADE6, LEU1 and HIS3) editing was also achieved using crRNA array expressed by the fba1 promoter, reaching efficiency of 17% and 2.5%, respectively.

Komagataella phaffii (previously Pichia pastoris)

The methylotrophic yeast K. phaffii has been recognized as an industrially relevant workhorse to produce recombinant proteins. Lack of episomal plasmids and genetic engineering tools has hindered metabolic engineering of this promising host. Weninger et al. optimized CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in K. phaffii by comparing the cutting efficiency of GUT1 [78]. It was found that the RNA polymerase III promoters tested led to poor editing efficiency (0-31.7%) while the HHR-gRNA-HDV construct using TEF promoter achieved much higher cutting efficiency (87-94%). Duplexed editing efficiency of GUT1 and AOX1 achieved 69% when human codon optimized Cas9 was expressed under the HXT1 promoter and gRNA with the highest efficiency was used. In another work published by Weninger et al., CRISPR-Cas9 mediated HDR was investigated in a KU70-deficient K. phaffii strain [79]. When a marker-free linear donor cassette was co-transformed with a CRISPR plasmid targeting GUT1, integration efficiency of 78%-91% was obtained, which was 1.9-fold higher than that of the control (without CRISPR plasmid). It was also found that HDR efficiency was improved in wild type K. phaffii strain when the donor cassette was supplied on a circular or linearized plasmid containing an autonomous replicating sequence (ARS). Delivery of Cas9 and gRNA on an episomal plasmid to achieve genome editing in K. phaffi was also reported recently [80]. Editing efficiency of GUT1 was comparable to that obtained when Cas9 and gRNA was integrated. To achieve multiple genomic integration in K. phaffii, Liu et al. screened ten potential loci using an enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) cassette in a KU70 knock-out strain [81]. gRNAs with the highest targeting efficiency for each locus were identified. Three linear cassettes containing eGFP, mCherry and blue fluorescent protein (BFP) were combinatorically transformed with corresponding gRNA to achieve multiloci integration. It was observed that efficiency of 57.7% to 70%, 12.5% to 32.1% was obtained for double and triple integration, respectively. Yang and coworkers reported a CRISPR-Cas9 system in K. phaffii by genomic integration of codon optimized SpCas9 and episomal expression of gRNA flanked by HHR and HDV under the bidirectional HTX1 promoter [82]. It was found that the editing efficiency could reach 80% to 95% when six genes were targeted using this system. Duplexed gene editing was also tested using this system by expressing two gRNAs under the HTX1 promoter. However, zero to very low double knockout efficiency was observed.

Scheffersomyces stipitis

S. stipitis has gained increasing interest as a promising host for biomanufacturing due to its ability to consume xylose. Implementing a plasmid-based CRISPR-Cas9 system in S. stipitis required a stable episomal vector to deliver Cas9 and gRNA. This issue was addressed by identifying centromeric DNA sequence to help stabilize episomal plasmid [83]. Successful gene editing of ADE2 and TRP1 was achieved by expression of codon optimized Cas9 and gRNA under the SNR52 promoter on the engineered episomal plasmid. This system was then expanded to marker-less donor integration using HDR in a S. stipitis KU70 and KU80 double mutant strain [84]. It was found that donor DNA knock-in efficiency reached 73% to 83% when homologous arms (HAs) of various lengths (50 bp, 100 bp, 500 bp and 1 kb) were used.

Kluyveromyces lactis and Kluyveromyces marxianus

CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing of K. lactis and K. marxianus was first achieved by overexpressing the Cas9 under TEF promoter and gRNA flanked by HHR and HDV under TDH3 promoter of S. cerevisiae [85]. Targeting efficiency of ADE2 was found to be 54% and 100% in K. lactis and K. marxianus, respectively. It was also found that co-transformation of a donor DNA could improve the targeting efficiency in K. lactis to 96%. PCR analysis revealed some editing events were repaired by the donor DNA. This system was also highly efficient in diploid strain of K. marxianus, reaching 80% of editing efficiency of ADE2. Marker-less donor integration in K. marxianus was reported in another study [86]. Native SNR52 promoter of K. marxianus was employed to express gRNA. Donor cassette with 50 bp HAs was able to integrate into the URA3 locus and SED1 locus with an efficiency of 92% and 100% in a NHEJ-deficient strain. Lee et al. implemented the CRISPR-Cas9 system in K. marxianus by integrated expression of Cas9 under Lac4 promoter and gRNAs under SNR52 promoter [87]. Successful knockout of MATa3 gene was obtained using this system. Optimization of hybrid promoters for the expression of gRNAs in K. marxianus was performed in another report [88].It was found that the highest targeting efficiency (66%) of XYL2 (encoding xylitol dehydrogenase) was achieved using RPR1-tRNAGly promoter. This system was employed to disrupt seven alcohol dehydrogenase genes (ADH1-7) and alcohol-O-acetyltransferase gene (ATF) with targeting efficiency of 10% to 67%.

Ogataea polymorpha (previously Hansenula polymorpha)

Ogataea polymorpha is a thermo-tolerant methylotrophic yeast widely used to produce recombinant proteins. It is also endowed with ability to utilize a broad range of substrates including glycerol, glucose, xylose and cellobiose [89]. Numamoto et al. reported the editing of ADE12, PHO1, PHO11 and PHO84 using tRNACUG as promoter to express gRNA [90]. Targeting efficiency of 45% was reached for ADE12 while more modest editing efficiency (17-71%) was obtained for PHO1, PHO11 and PHO84. Juergens el al. implemented a different strategy to target ADE2 by using an HHR-gRNA-HDV fusion construct under the TDH3 promoter. It was found that outgrowth in liquid culture was needed to achieve observable cutting of ADE2. Cutting efficiency of ADE2 reached 31% and 61% after 48h and 96h of outgrowth, respectively. Further outgrowth didn′t improve the editing efficiency. Duplexed editing of ADE2 and YNR1 was performed by expressing an array of HHR-gRNA-HDV under the TDH3 promoter, reaching double knockout efficiency of 2%-5%. To establish a robust multiplexed genome editing tool in O. polymorpha, Wang et al. integrated the Cas9 expression cassette into the genome. The gRNA construct was expressed by SNR52 promoter of S. cerevisiae and integrated the ADE2 locus to facilitate the visual selection of positive red colonies [91]. Both expression cassette of Cas9 and gRNA can be excised by transforming proper linear DNA cassettes to allow iterative genome editing. Editing efficiency of LEU2 and URA3 reached 58% and 65%, respectively. Triple gene knockout of URA3, HIS3 and LEU2 by transforming a cassette of gRNA array was achieved with efficiency of 23.6%. Integration of the three gene resveratrol pathway into the URA3, HIS3 and LEU2 was obtained with efficiency of 30.5% by co-transforming three donor cassettes. Multi-copy integration of GFP and resveratrol pathway into the rDNA site was also achieved by targeting the rDNA region. It was found that up to 9.8 copies of the genes were integrated into the rDNA sites, leading to improved titer of resveratrol.

Issatchenkia orientalis

Issatchenkia orientalis is a non-conventional yeast which has been exploited to produce organic acids such as succinic acid [92] due to its tolerance to low pH. Efforts have been made to enable metabolic engineering of this promising host by the development of a CRISPR-Cas9 based gene knockout tool [93]. Similar to other non-conventional yeasts, lack of stable episomal plasmid needs to be addressed to allow expression of Cas9 and gRNA. Tran et al. constructed a plasmid based on the S. cerevisiae ARS to achieve stable expression of GFP in this yeast. Suitable promoter for gRNA expression was identified by screening a series of RNA polymerase III promoters to target ADE2 gene. It was observed that the highest cutting efficiency was obtained using a hybrid RPR1′-tRNALeu promoter. Targeting efficiency of single gene knockout (LEU2, HIS3 and TRP1) reached near 100%. Triplexed editing of ADE2, HIS3 and SDH2 was achieved with 46.7% efficiency. Cao et al. reported a suite of genetic toolbox for rapid metabolic engineering in I. orientalis by identifying centromeric DNA sequence to enhance gene expression from episomal plasmid, characterizing various promoters, terminators and in vivo DNA assembly [94].

Candida tropicalis, Candida albicans

C. tropicalis is a pathogenic yeast which can accumulate high titer of long chain dicarboxylic acid [95]. A CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing system was recently developed for C. tropicalis [96]. Codon optimized SppCas9 was expressed under the GAP1 promoter and HHR-gRNA-HDV was expressed under the FBA1 promoter. Both integrated and transient CRISPR-Cas9-gRNA cassette can efficiently target the URA3 gene when a donor DNA with 50 bp homologous arms was supplied. It was also found that combining donor DNA and the CRISPR-Cas9-gRNA in one cassette significantly enhanced the editing efficiency of ADE2 than a separate donor DNA. Duplexed editing of URA3 and ADE2 was achieved by transforming a cassette with Cas9, two gRNAs and two donor DNA, obtaining an efficiency of 32%.

C. albicans is human pathogen which can cause fatal infections. Genome editing of this diploid yeast species could accelerate the discovery of potential antifungal drugs. Vyas et al. described a CRISPR system by expressing codon optimized Cas9 from ENO1 promoter and gRNA from SNR52 promoter on an integrated cassette [97]. This system was able to efficiently target various genes including ADE2, URA3, RAS1, MtlA1 and TPK2. It was also found that this CRISPR-Cas9 system could target genes with homology such as CDR1 and CDR2 with 20% efficiency. Transient expression of Cas9 and gRNA was also able to target ADE2 when a donor cassette was supplied [98]. Nguyen developed a rapid and recyclable CRISPR system by using leucine auxotrophy or the FLP-FRT system to excise the Cas9 and gRNA cassette from C. albicans genome [99].

Yeast genome editing using base editors

CRISPR-Cas based genome editing generates DSB to modify target DNA. Base editing is a novel genome editing technology to introduce point mutations without DNA cleavage in non-dividing cells, which has great potential in genome editing and gene therapy. Catalytically deficient Cas9 effector is employed to recruit gRNA to the target locus. Deaminase fused to dCas9 converts cytidine to uridine or adenine to guanine on the noncomplementary strand [100]. Base editors function in an activity window, meaning that all cytidine bases within this window could be targeted. To reduce the off-target effect of base editor, Tan et al. implemented two strategies by engineering the rigidity of linker between the dCas9 domain and the deaminase domain and fusion of truncated deaminase to dCas9 [101]. Target-AID base editor was constructed in S. cerevisiae by using a protein complex of dCas9 and PmCDA1 [102]. It was found that expression of dCas9-PmCDA1 or nCas9-PmCDA1 could mediate efficient point mutation of CAN1 and ADE1. Efficiency of double editing of CAN1 and ADE1 was found to be 31%. Recently, the Target-AID base editor was adapted in Y. lipolytica by using the nCas9-pmCDA1 fusion protein [103]. TRP1 gene was targeted by introducing a nonsense mutation. It was found that no mutation was observed when nCas9-pmCDA1 or nCas9-pmCDA1-UGI was expressed. Outgrowth of 24h was performed and base editing occurred only in the KU70 knockout strain with efficiency of 28% after 96h of growth. It was also revealed that deletion of KU70 can improve the base editing accuracy by installing the desired mutation while more indel mutations occurred in the wild type strain. Multiplexed base editing was also achieved by expressing multiple gRNAs and base editor on a single plasmid. It was reported that duplexed base editing of TRP1 and PEX10 achieved efficiency of 31% after 96h of outgrowth while triple editing was not observed. Despite base editing is less commonly used compared with regular CRISPR-Cas genome editing, it could be a useful supplementary genome editing tool due to its simplicity, DSB- and donor-free procedure.

Emerging CRISPR technologies for yeast genome editing

Base editors can introduce four types of transition mutations. However, transversion mutations such as adenine to thymidine is needed to correct sickle cell disease (SCD). Recently, a novel base editing technology termed prime editing which was able to perform all 12 possible base-to-base mutations, insertions and deletions without DSB or donor DNA was reported [104]. Prime editors consist of prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA), Cas9 nickase (nCas9) fused to an engineered reverse transcriptase (RT). The pegRNA contains a sgRNA that directs nCas9 to the target site and primer binding site (PBS) which includes new genetic information and hybridizes with the PAM strand. Nicking of the PAM strand and hybridization between PBS and PAM strand will initiate reverse transcription to directly install the edit into the target site. The authors developed three prime editors: PE1, PE2 and PE3. In PE1, wild-type Maloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) RT was fused to nCas9 and detectable editing was observed. To enhance the editing efficiency, five mutations were introduced to enhance the thermostability, processivity and DNA-RNA substrate affinity of M-MLV RT. The engineered RT was used in PE2 and improved the editing efficiency by 5.1-fold compared with PE1. In PE3, a second sgRNA was used to nick the non-target strand to direct DNA repair machinery to replace the original strand with the edited strand. This further enhance the editing efficiency by 4.2-fold compared with PE2. The prime editors described here could be a powerful and versatile genome editing toolbox for yeast genome editing in the future.

Comparison of genome editing systems

Various yeast genome editing systems were discussed in this review and a comparison of the yeast genome editing systems was summarized in Table 1. In most yeasts where NHEJ is the dominant repair mechanism, construction of mutant library via NHEJ is a viable strategy due to the random repair in yeast genome. However, HR is preferred to NHEJ as HR offers a more precise and predictable genome engineering approach for rational metabolic engineering. Non-Cas9 mediated HR is still widely employed to disrupt genes and integrate metabolic pathway into yeast genome, despite the low integration efficiency for large size DNA cassettes. HR remains the go-to technique particularly for non-conventional yeast when other genome editing tools are not readily available. Knockout of KU70 or KU80 gene is a common and effective strategy to enhance HR efficiency not by increasing HR rates but by decreasing NHEJ rates. Serine integrase mediated integration is mainly exploited as a tool to integrate large cassettes into genome; however, these methods still require integration of the attachment sites. Serine integrases could also be used to achieve high throughput DNA assembly and integration in single transformation step. TALEN could be used for multiplexed and genome scale engineering; however, its application in yeast genome engineering may be hindered by the cost and complexity of DNA assembly of TALEN. CRISPR-Cas based genome editing is showing great promise in yeast genome engineering due to its programmability and multiplexing. Design of efficient guides and assembly of gRNA array to target large number of genes is still the main challenge that needs to be addressed. Given the natural processing of Cas12a gRNA arrays, it may be preferred for multiplex applications. Base editing methods, including prime editing, are well suited for making point mutations, such as introduction of stop codons.

Perspectives

Yeast has become a promising chassis to address challenges in growing demand of a sustainable economy. Construction of cost-effective yeast cell factories is driven by the development of genome editing tools. CRISPR-Cas system has been successfully implemented mainly in genome engineering of S. cerevisiae. Development of CRISPR-Cas genome editing system in other non-conventional yeasts was bottlenecked by the lack of suitable promoters for the expression of Cas9 and gRNA. Based on literature, a strong promoter typically drives the expression of Cas9, and increasingly. tRNA and hybrid RNA polymerase II gene promoters are successful for gRNA processing and multiplexing.

Multiplexed genome editing would be accelerated by rapid assembly of multiple gRNAs [105,106]. CRISPR systems using orthogonal Cas effectors to simultaneously achieve gene activation, gene repression and gene deletion have been described [107]. This strategy could be a promising approach to achieve high throughput metabolic engineering of yeast cell factories. Engineered Cas effector variants with improved genome editing efficiency, reduced off-target effect [108] and altered PAM preference [109] could be expanded to yeast genome editing to facilitate strain engineering. Cas12a is likely to be more used for multiplex genome engineering.

Given the increasing interest in non-conventional yeast in biotechnology, a further expansion of genome editing tools will be needed; however, direct translation from S. cerevisiae into these systems is unlikely due to differences in the propensity for DSB repair by NHEJ. Therefore, we expect that genome engineering strategies that don’t rely on HDR, such as serine integrases, will begin to play a more central role, especially when combined with genome scale libraries and larger metabolic pathways.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R35GM133803. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- ARS:

autonomous replicating sequence

- BFP:

blue fluorescent protein

- CS:

cutting score

- CDS:

coding sequence

- CRISPR:

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat

- DBTL:

design build test learn

- DSB:

double strand break

- FS:

fitness score

- GFP:

green fluorescent protein

- GRAS:

generally regarded as safe

- HA:

homologous arm

- HDR:

homology directed repair

- HDV:

hepatitis delta virus

- HR:

homologous recombination

- HHR:

hammer head ribozyme

- MAGE:

Multiplexed automated genome scale engineering

- MMEJ:

microhomology-mediated end-joining

- M-MLV:

Maloney murine leukemia virus

- NHEJ:

non-homologous end joining

- nCas9:

Cas9 nickase

- PAM:

protospacer adjacent motif

- PBS:

primer binding site

- pegRNA:

prime editing guide RNA

- RT:

reverse transcriptase

- RVD:

variable di-residue

- SCD:

sickle cell disease

- sgRNA:

single guide RNA

- TALEN:

transcription activator like effector nuclease

- TAME:

TALEN assisted multiplexed editing

- YFP:

yellow fluorescent protein

- YOGE:

yeast oligo genome engineering

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Yang Z, Zhang Z: Engineering strategies for enhanced production of protein and bioproducts in Pichia pastoris: a review. Biotechnology advances 2018, 36:182–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cregg JM, Cereghino JL, Shi J, Higgins DR: Recombinant protein expression in Pichia pastoris. Molecular biotechnology 2000, 16:23–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paddon CJ, Keasling JD: Semi-synthetic artemisinin: a model for the use of synthetic biology in pharmaceutical development. Nat Rev Microbiol 2014, 12:355–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu P, Qiao K, Ahn WS, Stephanopoulos G: Engineering Yarrowia lipolytica as a platform for synthesis of drop-in transportation fuels and oleochemicals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113:10848–10853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xue Z, Sharpe PL, Hong S-P, Yadav NS, Xie D, Short DR, Damude HG, Rupert RA, Seip JE, Wang J: Production of omega-3 eicosapentaenoic acid by metabolic engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica. Nature biotechnology 2013, 31:734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin J, Wang Y, Yao M, Gu X, Li B, Liu H, Ding M, Xiao W, Yuan Y: Astaxanthin overproduction in yeast by strain engineering and new gene target uncovering. Biotechnology for biofuels 2018, 11:230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer CM, Miller KK, Nguyen A, Alper HS: Engineering 4-coumaroyl-CoA derived polyketide production in Yarrowia lipolytica through a β-oxidation mediated strategy. Metabolic engineering 2020, 57:174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Näätsaari L, Mistlberger B, Ruth C, Hajek T, Hartner FS, Glieder A: Deletion of the Pichia pastoris KU70 homologue facilitates platform strain generation for gene expression and synthetic biology. PloS one 2012, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao D, Smith S, Spagnuolo M, Rodriguez G, Blenner M: Dual CRISPR- Cas9 cleavage mediated gene excision and targeted integration in Yarrowia lipolytica. Biotechnology journal 2018, 13:1700590.* Use of two CRISPR-Cas9 cut sites enables efficient cleavage and gene integration in a single markerless step without selective profession.

- 10.Cai P, Gao J, Zhou Y: CRISPR-mediated genome editing in non-conventional yeasts for biotechnological applications. Microbial cell factories 2019, 18:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stovicek V, Holkenbrink C, Borodina I: CRISPR/Cas system for yeast genome engineering: advances and applications. FEMS yeast research 2017, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raschmanová H, Weninger A, Glieder A, Kovar K, Vogl T: Implementing CRISPR-Cas technologies in conventional and non-conventional yeasts: current state and future prospects. Biotechnology advances 2018, 36:641–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Löbs A-K, Schwartz C, Wheeldon I: Genome and metabolic engineering in non-conventional yeasts: current advances and applications. Synthetic and systems biotechnology 2017, 2:198–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies BG, Adams CL, Aijaz S, Cox JP: Towards a Cre-based recombination system for generating integrated DNA repertoires site-specifically in yeast. Biotechnology letters 2002, 24:727–733. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sauer B: Functional expression of the cre-lox site-specific recombination system in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular and cellular biology 1987, 7:2087–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fickers P, Le Dall M, Gaillardin C, Thonart P, Nicaud J: New disruption cassettes for rapid gene disruption and marker rescue in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Journal of microbiological methods 2003, 55:727–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lv Y, Edwards H, Zhou J, Xu P: Combining 26s rDNA and the Cre-loxP system for iterative gene integration and efficient marker curation in Yarrowia lipolytica. ACS synthetic biology 2019, 8:568–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ribeiro O, Gombert AK, Teixeira JA, Domingues L: Application of the Cre-loxP system for multiple gene disruption in the yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus. Journal of biotechnology 2007, 131:20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qian W, Song H, Liu Y, Zhang C, Niu Z, Wang H, Qiu B: Improved gene disruption method and Cre-loxP mutant system for multiple gene disruptions in Hansenula polymorpha. Journal of microbiological methods 2009, 79:253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dymond J, Boeke J: The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SCRaMbLE system and genome minimization. Bioengineered 2012, 3:170–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solis-Escalante D, van den Broek M, Kuijpers NG, Pronk JT, Boles E, Daran J-M, Daran-Lapujade P: The genome sequence of the popular hexose-transport-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain EBY. VW4000 reveals Lox P/Cre-induced translocations and gene loss. FEMS yeast research 2015, 15:fou004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snoeck N, De Mol ML, Van Herpe D, Goormans A, Maryns I, Coussement P, Peters G, Beauprez J, De Maeseneire SL, Soetaert W: Serine integrase recombinational engineering (SIRE): A versatile toolbox for genome editing. Biotechnology and bioengineering 2019, 116:364–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang H, Chai C, Yang S, Jiang W, Gu Y: Phage serine integrase-mediated genome engineering for efficient expression of chemical biosynthetic pathway in gas-fermenting Clostridium ljungdahlii. Metabolic engineering 2019, 52:293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colloms SD, Merrick CA, Olorunniji FJ, Stark WM, Smith MC, Osbourn A, Keasling JD, Rosser SJ: Rapid metabolic pathway assembly and modification using serine integrase site-specific recombination. Nucleic acids research 2014, 42:e23–e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu Z, Brown WR: Comparison and optimization of ten phage encoded serine integrases for genome engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC biotechnology 2016, 16:13.** A comprehensive study that demonstrated ten unidirectional serine integrases were active in yeast.

- 26.Bogdanove AJ, Voytas DF: TAL effectors: customizable proteins for DNA targeting. Science 2011, 333:1843–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christian M, Cermak T, Doyle EL, Schmidt C, Zhang F, Hummel A, Bogdanove AJ, Voytas DF: Targeting DNA double-strand breaks with TAL effector nucleases. Genetics 2010, 186:757–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carroll D: Genome engineering with targetable nucleases. Annual review of biochemistry 2014, 83:409–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li T, Huang S, Zhao X, Wright DA, Carpenter S, Spalding MH, Weeks DP, Yang B: Modularly assembled designer TAL effector nucleases for targeted gene knockout and gene replacement in eukaryotes. Nucleic acids research 2011, 39:6315–6325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aouida M, Li L, Mahjoub A, Alshareef S, Ali Z, Piatek A, Mahfouz MM: Transcription activator-like effector nucleases mediated metabolic engineering for enhanced fatty acids production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of bioscience and bioengineering 2015, 120:364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rigouin C, Gueroult M, Croux C, Dubois G, Borsenberger V, Barbe S, Marty A, Daboussi F, André I, Bordes F: Production of medium chain fatty acids by Yarrowia lipolytica: combining molecular design and TALEN to engineer the fatty acid synthase. ACS synthetic biology 2017, 6:1870–1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang G, Lin Y, Qi X, Li L, Wang Q, Ma Y: TALENs-assisted multiplex editing for accelerated genome evolution to improve yeast phenotypes. ACS synthetic biology 2015, 4:1101–1111.** Ethanol tolerance was engineered using indels created by TALENs targetting between the TATA and GC boxes.

- 33.Gan Y, Lin Y, Guo Y, Qi X, Wang Q: Metabolic and genomic characterisation of stress-tolerant industrial Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains from TALENs-assisted multiplex editing. FEMS yeast research 2018, 18:foy045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V: Cas9–crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109:E2579–E2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Mali P, Rios X, Aach J, Church GM: Genome engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nucleic acids research 2013, 41:4336–4343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bao Z, Xiao H, Liang J, Zhang L, Xiong X, Sun N, Si T, Zhao H: Homology-integrated CRISPR–Cas (HI-CRISPR) system for one-step multigene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. ACS synthetic biology 2014, 4:585–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mans R, van Rossum HM, Wijsman M, Backx A, Kuijpers NG, van den Broek M, Daran-Lapujade P, Pronk JT, van Maris AJ, Daran J-MG: CRISPR/Cas9: a molecular Swiss army knife for simultaneous introduction of multiple genetic modifications in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS yeast research 2015, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horwitz AA, Walter JM, Schubert MG, Kung SH, Hawkins K, Platt DM, Hernday AD, Mahatdejkul-Meadows T, Szeto W, Chandran SS: Efficient multiplexed integration of synergistic alleles and metabolic pathways in yeasts via CRISPR-Cas. Cell systems 2015, 1:88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan OW, Skerker JM, Maurer MJ, Li X, Tsai JC, Poddar S, Lee ME, DeLoache W, Dueber JE, Arkin AP: Selection of chromosomal DNA libraries using a multiplex CRISPR system. Elife 2014, 3:e03703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Wang J, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Shi S, Nielsen J, Liu Z: A gRNA-tRNA array for CRISPR-Cas9 based rapid multiplexed genome editing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature communications 2019, 10:1–10.** Demonstrated 87% efficiency disrupting 8 genes and a direct transformation Golden Gate variation that led to 30-fold incerase in free fatty acids in only 10 days of construction.

- 41.Zetsche B, Heidenreich M, Mohanraju P, Fedorova I, Kneppers J, DeGennaro EM, Winblad N, Choudhury SR, Abudayyeh OO, Gootenberg JS: Multiplex gene editing by CRISPR–Cpf1 using a single crRNA array. Nature biotechnology 2017, 35:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verwaal R, Buiting-Wiessenhaan N, Dalhuijsen S, Roubos JA: CRISPR/Cpf1 enables fast and simple genome editing of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 2018, 35:201–211.* First demonstration of CRISPR-Cpf1 function in yeast cells.

- 43.Li Z-H, Wang F-Q, Wei D-Z: Self-cloning CRISPR/Cpf1 facilitated genome editing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Bioresources and Bioprocessing 2018, 5:36. [Google Scholar]

- 44.DiCarlo JE, Conley AJ, Penttila M, Jantti J, Wang HH, Church GM: Yeast oligo-mediated genome engineering (YOGE). ACS Synth Biol 2013, 2:741–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barbieri EM, Muir P, Akhuetie-Oni BO, Yellman CM, Isaacs FJ: Precise Editing at DNA Replication Forks Enables Multiplex Genome Engineering in Eukaryotes. Cell 2017, 171:1453–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Si T, Chao R, Min Y, Wu Y, Ren W, Zhao H: Automated multiplex genome-scale engineering in yeast. Nat Commun 2017, 8:15187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bao Z, HamediRad M, Xue P, Xiao H, Tasan I, Chao R, Liang J, Zhao H: Genome-scale engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with single-nucleotide precision. Nat Biotechnol 2018, 36:505–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jakociunas T, Pedersen LE, Lis AV, Jensen MK, Keasling JD: CasPER, a method for directed evolution in genomic contexts using mutagenesis and CRISPR/Cas9. Metab Eng 2018, 48:288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qiao K, Imam Abidi SH, Liu H, Zhang H, Chakraborty S, Watson N, Kumaran Ajikumar P, Stephanopoulos G: Engineering lipid overproduction in the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Metab Eng 2015, 29:56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blazeck J, Hill A, Liu L, Knight R, Miller J, Pan A, Otoupal P, Alper HS: Harnessing Yarrowia lipolytica lipogenesis to create a platform for lipid and biofuel production. Nature communications 2014, 5:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qiao K, Wasylenko TM, Zhou K, Xu P, Stephanopoulos G: Lipid production in Yarrowia lipolytica is maximized by engineering cytosolic redox metabolism. Nature biotechnology 2017, 35:173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodriguez GM, Hussain MS, Gambill L, Gao D, Yaguchi A, Blenner M: Engineering xylose utilization in Yarrowia lipolytica by understanding its cryptic xylose pathway. Biotechnology for biofuels 2016, 9:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spagnuolo M, Shabbir Hussain M, Gambill L, Blenner M: Alternative substrate metabolism in Yarrowia lipolytica. Frontiers in microbiology 2018, 9:1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao S, Tong Y, Zhu L, Ge M, Zhang Y, Chen D, Jiang Y, Yang S: Iterative integration of multiple-copy pathway genes in Yarrowia lipolytica for heterologous beta-carotene production. Metab Eng 2017, 41:192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Larroude M, Celinska E, Back A, Thomas S, Nicaud JM, Ledesma-Amaro R: A synthetic biology approach to transform Yarrowia lipolytica into a competitive biotechnological producer of beta-carotene. Biotechnol Bioeng 2018, 115:464–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu H, Marsafari M, Wang F, Deng L, Xu P: Engineering acetyl-CoA metabolic shortcut for eco-friendly production of polyketides triacetic acid lactone in Yarrowia lipolytica. bioRxiv 2019:614131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Markham KA, Palmer CM, Chwatko M, Wagner JM, Murray C, Vazquez S, Swaminathan A, Chakravarty I, Lynd NA, Alper HS: Rewiring Yarrowia lipolytica toward triacetic acid lactone for materials generation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115:2096–2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cao X, Lv YB, Chen J, Imanaka T, Wei LJ, Hua Q: Metabolic engineering of oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica for limonene overproduction. Biotechnol Biofuels 2016, 9:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu Y, Jiang X, Cui Z, Wang Z, Qi Q, Hou J: Engineering the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica for production of α-farnesene. Biotechnology for Biofuels 2019, 12:296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shi T-Q, Huang H, Kerkhoven EJ, Ji X-J: Advancing metabolic engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica using the CRISPR/Cas system. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2018, 102:9541–9548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schwartz CM, Hussain MS, Blenner M, Wheeldon I: Synthetic RNA polymerase III promoters facilitate high-efficiency CRISPR–Cas9-mediated genome editing in Yarrowia lipolytica. ACS synthetic biology 2016, 5:356–359.** The first demonstration of CRISPR-Cas9 in Yarrowia lipolytica, using hybrid RNA-polymerase III promoters.

- 62.Schwartz C, Shabbir-Hussain M, Frogue K, Blenner M, Wheeldon I: Standardized Markerless Gene Integration for Pathway Engineering in Yarrowia lipolytica. ACS Synth Biol 2017, 6:402–409.* Reliable markerless integration sites were identified that are compatable with CRISPR-Cas9.

- 63.Holkenbrink C, Dam MI, Kildegaard KR, Beder J, Dahlin J, Domenech Belda D, Borodina I: EasyCloneYALI: CRISPR/Cas9-Based Synthetic Toolbox for Engineering of the Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Biotechnol J 2018, 13:e1700543.** A highly efficient Cas9 and marker-mediated system, containing vectors for integration at several genomic loci.

- 64.Gao S, Tong Y, Wen Z, Zhu L, Ge M, Chen D, Jiang Y, Yang S: Multiplex gene editing of the Yarrowia lipolytica genome using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2016, 43:1085–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang Z, Edwards H, Xu P: CRISPR-Cas12a/Cpf1-assisted precise, efficient and multiplexed genome-editing in Yarrowia lipolytica. Metabolic Engineering Communications 2019:e00112.* First demonstration of Cas12a (Cpf1) genome editing in Yarrowia lipolytica.

- 66.Ramesh A, Ong T, Garcia JA, Adams J, Wheeldon I: Guide RNA Engineering Enables Dual Purpose CRISPR-Cpf1 for Simultaneous Gene Editing and Gene Regulation in Yarrowia lipolytica. ACS Synth Biol 2020, 9:967–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schwartz C, Cheng J-F, Evans R, Schwartz CA, Wagner JM, Anglin S, Beitz A, Pan W, Lonardi S, Blenner M: Validating genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 function improves screening in the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Metabolic engineering 2019, 55:102–110.** A genome scale knockout library was created using nearly 50,000 gRNA sequences, leading to essential gene identifiication and improved phentotypes.

- 68.Yaegashi J, Kirby J, Ito M, Sun J, Dutta T, Mirsiaghi M, Sundstrom ER, Rodriguez A, Baidoo E, Tanjore D: Rhodosporidium toruloides: a new platform organism for conversion of lignocellulose into terpene biofuels and bioproducts. Biotechnology for biofuels 2017, 10:241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Otoupal PB, Ito M, Arkin AP, Magnuson JK, Gladden JM, Skerker JM: Multiplexed CRISPR-cas9-based genome editing of rhodosporidium toruloides. mSphere 2019, 4:e00099–00019.* Establishing and improving the use of Cas9 in R. toruloides required integration of the CRISPR casette and gRNA promoters using tRNA and excluding ribozyme sequences.

- 70.Jiao X, Zhang Y, Liu X, Zhang Q, Zhang S, Zhao ZK: Developing a CRISPR/Cas9 system for genome editing in the basidiomycetous yeast Rhodosporidium toruloides. Biotechnology journal 2019, 14:1900036.* A U6 promoter for the gRNA was used to achieve over 60% transformation efficiency.

- 71.Schultz JC, Cao M, Zhao H: Development of a CRISPR/Cas9 system for high efficiency multiplexed gene deletion in Rhodosporidium toruloides. Biotechnology and bioengineering 2019, 116:2103–2109.** Achieved over 95% knockout efficiency using a hybrid promoter of 5S rRNA-tRNA. Double knockouts occurred with 78% efficiency.

- 72.Hoffman CS, Wood V, Fantes PA: An ancient yeast for young geneticists: a primer on the Schizosaccharomyces pombe model system. Genetics 2015, 201:403–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jacobs JZ, Ciccaglione KM, Tournier V, Zaratiegui M: Implementation of the CRISPR-Cas9 system in fission yeast. Nature communications 2014, 5:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fernandez R, Berro J: Use of a fluoride channel as a new selection marker for fission yeast plasmids and application to fast genome editing with CRISPR/Cas9. Yeast 2016, 33:549–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang X-R, He J-B, Wang Y-Z, Du L-L: A cloning-free method for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in fission yeast. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 2018, 8:2067–2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hayashi A, Tanaka K: Short-homology-mediated CRISPR/Cas9-based method for genome editing in fission yeast. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 2019, 9:1153–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhao Y, Boeke JD: CRISPR–Cas12a system in fission yeast for multiplex genomic editing and CRISPR interference. Nucleic Acids Research 2020, 48:5788–5798.* Demonstrated the use of RNA polymerase II promoter for expression of Cas12a in S. pombe.

- 78.Weninger A, Hatzl AM, Schmid C, Vogl T, Glieder A: Combinatorial optimization of CRISPR/Cas9 expression enables precision genome engineering in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. J Biotechnol 2016, 235:139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Weninger A, Fischer JE, Raschmanova H, Kniely C, Vogl T, Glieder A: Expanding the CRISPR/Cas9 toolkit for Pichia pastoris with efficient donor integration and alternative resistance markers. J Cell Biochem 2018, 119:3183–3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gu Y, Gao J, Cao M, Dong C, Lian J, Huang L, Cai J, Xu Z: Construction of a series of episomal plasmids and their application in the development of an efficient CRISPR/Cas9 system in Pichia pastoris. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2019, 35:79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu Q, Shi X, Song L, Liu H, Zhou X, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Cai M: CRISPR–Cas9-mediated genomic multiloci integration in Pichia pastoris. Microbial cell factories 2019, 18:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang Y, Liu G, Chen X, Liu M, Zhan C, Liu X, Bai Z: High efficiency CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing system with an eliminable episomal sgRNA plasmid in Pichia pastoris. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 2020:109556.* Identified CGG as the preferable PAM sequence amongst NGG sites.

- 83.Cao M, Gao M, Lopez-Garcia CL, Wu Y, Seetharam AS, Severin AJ, Shao Z: Centromeric DNA facilitates nonconventional yeast genetic engineering. ACS synthetic biology 2017, 6:1545–1553.** First example of CRISPR-Cas9 in S. stipitis, using a double knockout of ku70/ku80 and a novel episomal plasmid.

- 84.Cao M, Gao M, Ploessl D, Song C, Shao Z: CRISPR–mediated genome editing and gene repression in Scheffersomyces stipitis. Biotechnology journal 2018, 13:1700598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Juergens H, Varela JA, Gorter de Vries AR, Perli T, Gast VJM, Gyurchev NY, Rajkumar AS, Mans R, Pronk JT, Morrissey JP, et al. : Genome editing in Kluyveromyces and Ogataea yeasts using a broad-host-range Cas9/gRNA co-expression plasmid. FEMS Yeast Res 2018, 18.** Ribozyme-flanked gRNA was expressed from a plasmid containing a multispecies origin, demonstrating effective knockout and homologous recombination in Kluyveromyces and much less effective results in Ogataea.

- 86.Nambu-Nishida Y, Nishida K, Hasunuma T, Kondo A: Development of a comprehensive set of tools for genome engineering in a cold-and thermo-tolerant Kluyveromyces marxianus yeast strain. Scientific reports 2017, 7:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lee M-H, Lin J-J, Lin Y-J, Chang J-J, Ke H-M, Fan W-L, Wang T-Y, Li W-H: Genome-wide prediction of CRISPR/Cas9 targets in Kluyveromyces marxianus and its application to obtain a stable haploid strain. Scientific reports 2018, 8:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Löbs A-K, Engel R, Schwartz C, Flores A, Wheeldon I: CRISPR–Cas9-enabled genetic disruptions for understanding ethanol and ethyl acetate biosynthesis in Kluyveromyces marxianus. Biotechnology for biofuels 2017, 10:164.* First demonstration of CRISPR-Cas9 in K. marxianus enabled by hyrbid RNA polymerase III promoters.

- 89.Manfrão-Netto JH, Gomes AM, Parachin NS: Advances in using Hansenula polymorpha as chassis for recombinant protein production. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 2019, 7:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Numamoto M, Maekawa H, Kaneko Y: Efficient genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 with a tRNA-sgRNA fusion in the methylotrophic yeast Ogataea polymorpha. Journal of bioscience and bioengineering 2017, 124:487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang L, Deng A, Zhang Y, Liu S, Liang Y, Bai H, Cui D, Qiu Q, Shang X, Yang Z: Efficient CRISPR–Cas9 mediated multiplex genome editing in yeasts. Biotechnology for biofuels 2018, 11:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Xiao H, Shao Z, Jiang Y, Dole S, Zhao H: Exploiting Issatchenkia orientalis SD108 for succinic acid production. Microbial cell factories 2014, 13:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tran VG, Cao M, Fatma Z, Song X, Zhao H: Development of a CRISPR/Cas9-Based Tool for Gene Deletion in Issatchenkia orientalis. mSphere 2019, 4:e00345–00319.** First demonstration of functional CRISPR-Cas9 using hybrid RNA polymerase III promoter from a plasmid with a Saccharomyces ARS.

- 94.Cao M, Fatma Z, Song X, Hsieh P-H, Tran VG, Lyon WL, Sayadi M, Shao Z, Yoshikuni Y, Zhao H: A genetic toolbox for metabolic engineering of Issatchenkia orientalis. Metabolic Engineering 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang J, Peng J, Fan H, Xiu X, Xue L, Wang L, Su J, Yang X, Wang R: Development of mazF-based markerless genome editing system and metabolic pathway engineering in Candida tropicalis for producing long-chain dicarboxylic acids. Journal of industrial microbiology & biotechnology 2018, 45:971–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhang L, Zhang H, Liu Y, Zhou J, Shen W, Liu L, Li Q, Chen X: A CRISPR–Cas9 system for multiple genome editing and pathway assembly in Candida tropicalis. Biotechnology and bioengineering 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vyas VK, Barrasa MI, Fink GR: A Candida albicans CRISPR system permits genetic engineering of essential genes and gene families. Science advances 2015, 1:e1500248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Min K, Ichikawa Y, Woolford CA, Mitchell AP: Candida albicans gene deletion with a transient CRISPR-Cas9 system. mSphere 2016, 1:e00130–00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nguyen N, Quail MM, Hernday AD: An efficient, rapid, and recyclable system for CRISPR-mediated genome editing in Candida albicans. MSphere 2017, 2:e00149–00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR: Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 2016, 533:420–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tan J, Zhang F, Karcher D, Bock R: Engineering of high-precision base editors for site-specific single nucleotide replacement. Nature communications 2019, 10:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nishida K, Arazoe T, Yachie N, Banno S, Kakimoto M, Tabata M, Mochizuki M, Miyabe A, Araki M, Hara KY: Targeted nucleotide editing using hybrid prokaryotic and vertebrate adaptive immune systems. Science 2016, 353:aaf8729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bae SJ, Park BG, Kim BG, Hahn JS: Multiplex Gene Disruption by Targeted Base Editing of Yarrowia lipolytica Genome Using Cytidine Deaminase Combined with the CRISPR/Cas9 System. Biotechnology journal 2019:1900238.** First demonstration of base editors in Yarrowia lipolytica introduced premature stop codons for knockout creation.

- 104.Anzalone AV, Randolph PB, Davis JR, Sousa AA, Koblan LW, Levy JM, Chen PJ, Wilson C, Newby GA, Raguram A, et al. : Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 2019, 576:149–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.McCarty NS, Shaw WM, Ellis T, Ledesma-Amaro R: Rapid assembly of gRNA arrays via modular cloning in yeast. ACS synthetic biology 2019, 8:906–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Reis AC, Halper SM, Vezeau GE, Cetnar DP, Hossain A, Clauer PR, Salis HM: Simultaneous repression of multiple bacterial genes using nonrepetitive extra-long sgRNA arrays. Nature biotechnology 2019, 37:1294–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lian J, HamediRad M, Hu S, Zhao H: Combinatorial metabolic engineering using an orthogonal tri-functional CRISPR system. Nature communications 2017, 8:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kleinstiver BP, Sousa AA, Walton RT, Tak YE, Hsu JY, Clement K, Welch MM, Horng JE, Malagon-Lopez J, Scarfò I: Engineered CRISPR–Cas12a variants with increased activities and improved targeting ranges for gene, epigenetic and base editing. Nature biotechnology 2019, 37:276–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Walton RT, Christie KA, Whittaker MN, Kleinstiver BP: Unconstrained genome targeting with near-PAMless engineered CRISPR-Cas9 variants. Science 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]