Abstract

The aim of this work is to obtain better water resistance properties with additives to starch at the size press. A further goal is to replace petroleum-based additives with environmentally friendly hydrophobic agents obtained by derivatization of wood rosin. A crude wood rosin (CWR) sample was methylated and analyzed with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Methyl abietate, dehydroabietic acid, and abietic acid were the main constituents of the sample. The crude wood rosin samples were fortified with fumaric acid and then esterified with pentaerythritol. Fortified and esterified wood rosin samples were dissolved in ethanol and emulsified with cationic starch to make them suitable as hydrophobic additives for surface treatment formulations in mixtures with starch. These hydrophobic agents (2% on a dry weight basis in a cationic starch solution) were applied to paperboard, bleached kraft paper, and test liner paper using a rod coater with a target pickup of 3–5 gsm. The solution pickup was controlled by varying the rod number. The amounts of hydrophobic material applied in the preparation of the paper samples were 32.2, 48.6, and 35.1 lb/ton pickup compared to three types of base papers. Basic surface features of fortified and fortified and esterified rosin-treated paper were compared with base paper and paper treated with starch alone. Lower Cobb60 values were obtained for fortified and esterified samples than for linerboard samples that had been surface-sized just by starch. Thus, as novel hydrophobic additive agents, derivatives of CWR can be a green way to increase hydrophobicity while reducing starch consumption in papermaking.

Introduction

A key aim of sizing treatments of paper is to improve resistance to spreading and penetration by liquids.1−6 Conventionally, this has been achieved either by adding hydrophobic sizing agents to the fiber suspension in the wet end (internal sizing) or by adding hydrophobic agents together with a solution of starch applied to the surface of paper at the size press (a subclass of surface sizing). In printing applications, the surface of paper should exhibit sufficient resistance against applied liquids, but it also needs to absorb a sufficient amount of ink to achieve the desired print image density while minimizing the cost of the ink. Therefore, the paper surface needs to be prepared before printing applications, such as the offset and xerographic techniques, by use of a size press that exposes the paper web to a hot starch solution.6 The absorption capacity of printing ink is an important physical property of surface-treated paper,7 and it directly affects the quality of printed products. However, if there is excessive penetration of starch at the size press, then the web strength of the rewetted paper may be reduced sufficiently to increase the frequency of web breaks at the size press.

Considering end uses of products, test liner papers need to be able to protect corrugated boards against external factors, especially liquids, but at the same time, the board’s printability features should not be affected. Also, it is important to control the penetration of adhesives during the assembly of corrugated boards for packaging. Therefore, the method of application and amount of absorption of adhesives are of vital importance, and they affect the properties of the final products. Similarly, white top paperboard needs to have sufficient resistance to liquids to enable a uniform distribution of the coating material. A low water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) is expected for most of the commercial papers, especially packaging papers. It has been concluded that WVTR is controlled by gas diffusion through the pore system and depends strongly on the density of the paper sheets among various paper grades.8

Surface sizing is an appropriate way to confer desired surface properties to paper.9 A surface sizing agent forms a film layer in the surface sizing process.10,11 The critical issue for the paper is the degree of holdout that is obtained. As a step to achieving a sufficient surface sizing degree, a starch solution can be applied to the paper surface.10 While many paper manufacturers prefer to use oxidized starch at the size press due to its low cost, other paper manufacturers prefer to use cationic starch because of the finding that it largely remains on the paper surface and adds more stiffness to the paper.12 In addition, when the paper web breaks or when out of specification the paper is recycled back to the wet end of the paper machine, the cationic size press starch is retained well on the fibers and contributes to paper strength efficiently, while not making a major contribution to the biological oxygen demand of the effluent from the papermaking process.13 The application conditions for starch are an important factor affecting the machine speed and hence the runnability. Also, starch type is a crucial aspect in sizing efficiency. Oxidized starches and cationic starches are the most common in industry. Compared to oxidized starches, cationic starches improve the opacity, brightness, print gloss, and ink density of paper because of better holdout properties. Besides, the disadvantage of oxidized starches acting as anionic trash in the recycling process is eliminated with cationic starches.14 Compared to hydroxyethyl ether starches, the pickup rate of cationic starches is lower for various types of papers.15 Factors that need to be considered include the viscosity of the starch and the application temperature. The solid content of the sizing agent should be adjusted according to these two factors.

Re-wetting of the paper’s internal structure at the size press, followed by re-drying of the paper, can decrease the strength properties of paper, and it can damage the economic performance of the operation. A critical issue for the size-press starch is the degree of penetration.16,17 Nevertheless, papermakers often encounter undesirable situations such as insufficient internal sizing, leading to excessive penetration of the size-press formulation. In addition, deposition of the inkjet fluid, as well as the amount of liquid transferred to the paper during such printing, could be related to there being insufficient internal sizing.16 Also, the application of starch to the paper surface can decrease the linting effect at the paper surface in printing processes, especially offset lithographic printing.18 Therefore, the properties of a starch mixture need to be improved to promote the efficiency of the sizing agent.

Surface sizing application with the inclusion of hydrophobic copolymers is a common practice when internal sizing is not adequate. Such copolymers can be compatible with internal sizing agents in terms of sizing performance.16,19 Moreover, they could have a synergistic effect. Frequently, materials used in combination with starch may act as cobinders and help to overcome the insufficiency of sizing effects. In the case where the starch sizing agents cannot provide adequate holdout of liquids, rosin products can be used to improve the overall performance; this is an environmentally friendly approach due to the usage of bio-based materials as hydrophobic agents.20 Reliance upon biomaterials, including starch- and rosin-based sizing agents, may be a wise way to reduce petroleum-based materials, which have become disfavored due to low recyclability, poor biodegradation, and recyclability concerns.21 The rosin sizing treatment can also be used as an approach for preparation of antimicrobial packaging, in addition to rosin’s role in achieving the hydrophobic character of paper surfaces.22

Rosin esters and fortified rosin products are common rosin derivatives. Also, it has been shown that tall oil rosin can decrease curling and pinhole density of the coating material.20 Carboxylic groups of rosin can be coupled to fumaric acid. Rosin adducts can be esterified with alcohols such as pentaerythritol.23 The use of rosin derivatives as surface sizing coating materials in aqueous dispersion is common. Such products include the amine salt of rosin acid, as has been disclosed in a patented formulation.24

The molecular size of rosin can be increased via fortification and esterification processes, which would provide preferable surface coverage. Also, these rosin derivatives can be used in various applications such as surface coating, paper sizing, varnishes, paints, etc.25−27 In the role of plasticizers, rosin derivatives are preferred as additives for making bio-based polymeric products.26,28 Therefore, these derivatives were prepared in the current work.

As a first step of the modification, the levopimaric acid molecule of the abietadienoic class has been emphasized as being capable of undergoing Diels–Alder (fortification) reactions.29 During chemical modification, thermal isomerization occurs between the groups of abietadienoic acid, and all resin acids are converted into levopimaric acid, as well as conjugated double bonds are formed with fumaric acid or maleic acid anhydride.30−32

In the next stage, pentaerythritol is frequently used as a polyol in rosin esterification, as its neopentyl structure provides stability and four equally reactive hydroxyl groups allow high branching.27,33 As a primary step, crude wood rosin was used to prepare an adduct with fumaric acid anhydride by the Diels–Alder reaction. Then, pentaerythritol, a polyhydric alcohol, was selected for esterification of fortified rosin. Fumaric rosin penta-ester contains at least three hydroxyl groups, with two of the hydroxyl groups being terminal primary hydroxyl groups. These fumaric-modified rosin esters are characterized by their low acid number (less than 20, preferably 15–20) and a high degree of softening depending on the level of addition amount of pentaerythritol, depending on end-use production need.

Fortified maleic or fumaric rosins and rosin esters, which are forms of natural resins, are commonly applied in the internal sizing process. However, penta-ester rosin and fumarated rosins were applied in this work for the first time as a surface sizing additive.

Glycerol and pentaerythritol resin surface applications have been successfully found in the varnish application of wood-based materials, paint, and ink formulations. It is foreseen that the rosin and derivative products can form a film layer on the surface that will not allow water to penetrate. Its use in surface sizing formulations can be regarded as a challenge due to its water-insoluble structure. However, in this study, this challenge was overcome by dissolving the products in ethanol and then adding them to the cationic starch formulation. Both of the derivatized products were emulsified with cationic starch as a way of making suitable surface sizing agent formulations, which were applied to paper specimens and evaluated. It is believed that the growth in the molecular structure of the rosin as a result of the derivatization process is beneficial for spreading the surfaces.

Experimental Section

Materials

A crude wood rosin (CWR) sample isolated from pine stumps via hexane extraction was obtained from IVA Rosin Biomass company, Edremit, Turkey. The acid number of the CWR sample was 219 mg KOH/g (ASTM D664). Fumaric acid (CAS: 110-17-8) and pentaerythritol (CAS: 115-77-5) samples were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. A cationic starch ether sample was purchased from Solbond PC50 (cationic cook-up potato starch CAS: 56780-58-6). As base paper samples, a white top paperboard, linerboard (unbleached), and white kraft (WK) paper were selected.

Methods

The properties of the base paper samples were obtained using standard TAPPI methods for basis weight (T410) and a caliper (T411). After surface treatment and cylinder drying, the samples were kept for 24 h in a conditioning room at 23 °C and 50% relative humidity (RH). The air resistance of base papers and treated papers was analyzed using the T460 (Gurley porosity) method, based on the time for air flow of 100 cm3 through bleached kraft paper and 50 cm3 through test liner and paperboard samples. Then, the paper was evaluated for Cobb60 (T 441 om-09), water vapor transmission rate (using the ASTM E96 wet-cup method applied to the treated side), optical properties (ISO 2470-1, D65 illumination, 10° observation), and water vapor transmission weight (ASTM E96). The acid numbers of the rosin-derivatized samples were measured according to ASTM D664, and the softening point was evaluated using ASTM E28-18.

Analysis of Crude Wood Rosin by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS)

Crude wood rosin can be described as a raw material that can be solvent extracted (mostly using hexane) from coniferous wood stumps; it is then subjected to refining and fractionation steps.34 The chemical composition of the CWR is typically expected to consist of resin acids as well as turpentine, pine oil, pine tar, and other aliphatic hydrocarbons. Since the resin acids in the CWR are partly fragmented and partly become evident as a broad peak with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS), chemical modifications are required for the rapid and accurate detection of resin acids.35,36 Esterification with methanol is a convenient way of altering the features of rosin at high temperatures, so that they are quantified in their methyl ester forms.36,37 Thus, GC can be easily used in the analysis of rosin acids in the form of methyl esters. The methyl ester form of CWR was prepared according to the Sanderman method.38 During the chemical modifications of the fumarated adduct form and the penta-esterified form of the CWR made in the current study, turpentine, pine oils, aliphatic hydrocarbons, and other fragments with a boiling point of less than 230 °C were condensed by a heat treatment application. Thus, these chemical modifications were made only with resin acid fragments.

Preparation of Cationic Starch and Surface Treatment

Cationic starch was prepared with distilled water and heated using a mantle heater with constant stirring to a controlled temperature of 90–95 °C. The holding time at this temperature was not less than 15 min. The starch samples’ solid contents were 5, 7, and 10%, and viscosity was evaluated at 60 °C and 100 rpm using a Brookfield DV-II+ viscometer, with spindle 2. The values were 12, 36, and 51 cP, respectively. Common application conditions of starch surface treatment, for papermaking applications, are a temperature of 55–65 °C and a viscosity of 30–50 cP.39 Thus, a 7% solid content cationic starch solution was selected for surface treatment, allowing the comparison of the fortified and esterified forms of CWR added with starch sizing agents. Fortified crude wood rosin and fortified and esterified rosin samples were dissolved in ethanol and added to a 70 °C starch solution (2% on a dry weight basis in a cationic starch solution) under continuous stirring for 10 min at 1000 rpm and then applied at 60 °C.

Application of Surface Treatment and Optical Microscopy Images of the Surface

The hydrophobic agents were applied to base paper samples with a lab drawdown rod coating method. The applicator speed was 3 cm/s (RK print coat instrument, model K202) with all paper types. The #0 bar rod was used for bleached kraft sample coating (BK), whereas the #3 bar rod was used for white top cardboard (WTC) and test liner (TL) samples. After cationic starch application, basis weight changes of the paper samples were 4.8, 3.2, and 3.5 g/m2, respectively, compared to base papers, which consumed 31.2, 46.8, and 34.1 lb/ton pickup. After the surface treatment, paper samples were dried with a rotating drum at 100 °C at low speed and pressure to cure the hydrophobic agents, and they were kept at a constant temperature of 23 °C and 50% relative humidity for 24 h before testing of the paper. Hot-air drying or additional drying techniques were not applied prior to cylinder drying.

Penetration in the z-direction (interphase thickness) was studied by optical microscopy to compare surface treatment. Optical measurements were carried out conveniently by following the procedure of Shirazi et al.15 The cationic starch, fortified CWR blended starch, and fortified and esterified CWR blended starch-coated samples were cut into small pieces and immersed in an iodine solution as tracers (2 mg/L iodine, 20 mg/L potassium iodide) for 10 min. Then, they were immersed in deionized water for 10 min to remove the unbonded iodine from the paper. Treated samples were kept for 24 h in a conditioning room. Optical microscopy images in the z-direction were examined.

Results and Discussion

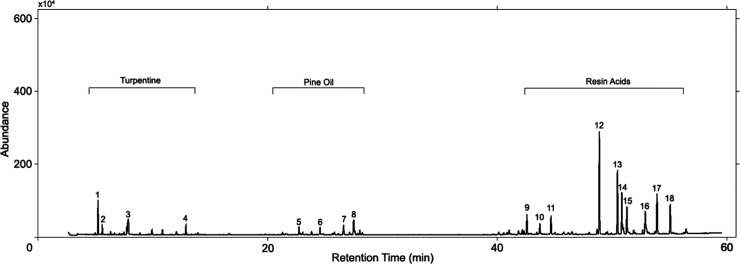

The composition of the methylated CWR sample was determined by GC–MS (Figure 1). As shown, there were 9–18 peaks that can be attributed to resin acid components and rosin acid methyl esters (methyl abietate (12), methyl dehydroabiatate (16), methyl pimarate (17), etc., but there were other isomers that were not clearly described), constituting 84% of the composition. In addition, there were 1–4 peaks that can be attributed to turpentine (α pinene (1), campene (2), limonene (4)), which constitute 12% of the composition. Around 5–8 peaks can be attributed to pine oil (α terpineolene (5), α murolene (7), delta cadinene (8)), which constitute 3% of the composition (list of compounds of methylated CWR given in Table S1 in the Supporting Information). Pine tar and other aliphatic hydrocarbons were not clearly described (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

GC–MS results of the methylated CWR sample.

The results differed from the literature in terms of the precise composition of wood rosin of commercial products. This can be understood based on the refining and fractionation steps, which eliminate other components, except resin acids.40−44 In the current study, the crude wood rosin samples were used directly for further modification, which involved fortification with fumaric acid and esterification with pentaerythritol.

Figure 2 shows the reaction diagram for preparation of fortified wood rosin with fumaric acid. The reaction for the fortified CWR sample was carried out in a three-neck reactor. The reaction was performed in an inert gas atmosphere (nitrogen), and then the reaction mixture was heated under continuous stirring. After decreasing the temperature of the crude rosin to 120 °C, fortification was carried out with fumaric anhydride to improve the performance and durability of surface sizing of paper.1,45,46 The crude wood rosin sample was fortified with 10% fumaric acid anhydride via the Diels–Alder reaction (Figure 2). Thus, carboxylic acid groups of rosin were coupled and formed fumaropimaric acid. The acid number of the fumarated CWR sample was 212 mg KOH/g, and the softening point was 102 °C (ASTM E28-18).

Figure 2.

Reaction diagram of fumarated CWR.

As it has been shown that fortification (a Diels–Alder reaction) of a partial proportion (2–8%) of abietic acid, which is a close relative of the levopimaric acid molecule, can yield better results of sizing,30 the crude wood rosin sample was fortified with 10% fumaric acid anhydride via the Diels–Alder reaction, and the samples were 10% esterified with pentaerythritol (Figure 3). The acid number of the fumarated and esterified CWR samples was 26 mg KOH/g, and the softening point was 124 °C.

Figure 3.

Esterification process of fumaric acid CWR.

For the preparation of the rosin-containing starch solutions, 2% of the rosin samples were dissolved in 10 mL of ethanol and added to 70 °C starch samples. The materials were emulsified with vigorous mixing at 2000 rpm. The CWR sample was treated in a three-neck reactor under atmospheric and reduced pressure. The esterification reaction was performed in an inert gas atmosphere, and then the reaction mixture was heated under continuous stirring in a similar way to that in a previous publication.32 Long reaction times are required to form rosin–pentaerythritol esters, but the molecular weight increased and the softening point decreased as a result. Such changes affect the compatibility properties of the hydrophobic agent. The stages of the experiment are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Summary of the reaction scheme and preparation of the hydrophobic agent solution.

The viscosities of formulations with fumarated and penta-ester forms of the CWR starch mixture, compared with the base starch solution itself, were evaluated at a 100 rpm mixing speed, and the values were 36, 32.3, and 31.7 cP, respectively. Properties before and after surface treatment are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Basic Properties and Coating Weight of Base Papers.

| before treatment |

cat. starch treatment only |

cat. starch + hydrophobic additive treatment |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| basis weight (g/m2) | caliper | Gurley porosity | basis weight (g/m2) | caliper | Gurley porosity | basis weight (g/m2) | caliper | Gurley porosity | |

| base paper type | (μ) | (s) | (μ) | (s) | (μ) | (s) | |||

| (T410) | (T411) | (T460) | (T410) | (T411) | (T460) | (T410) | (T411) | (T460) | |

| bleached kraft (BK) | 45 ± 2 | 46 ± 2 | 12 ± 1 | 49 ± 2 | 56 ± 2 | 21 ± 1 | 49 ± 2 | 52 ± 2 | 42 ± 1 |

| white top cartonboard (WTC) | 280 ± 5 | 350 ± 5 | 85 ± 1 | 285 ± 5 | 387 ± 5 | 151 ± 1 | 285 ± 5 | 379 ± 5 | 276 ± 1 |

| test liner (TL) | 180 ± 2 | 205 ± 5 | 56 ± 1 | 184 ± 2 | 217 ± 5 | 102 ± 1 | 184 ± 2 | 215 ± 5 | 169 ± 1 |

After treatment with fortified and fortified and esterified CWR, the paper exhibited pickup levels of 32.3, 48.6, and 35.1 lb/ton compared to the base papers BK, WTC, and TL, respectively. The addition of rosin derivatives to the starch solution provided improvement in air resistance, which resulted in less porous paper. The reason could be related to the ability of the fortified and fortified and esterified CWR with starch to form a more effective barrier layer near the paper’s surface. Such a layer, to the degree that it blocks pores near the paper surface, can be expected to decrease the water vapor transmission rate and increase the resistance to water penetration into the paper. The present results suggest that the barrier effects were superior to those achieved when starch was used by itself.

Optical Microscopy Results

The samples were labeled as follows: the letter S denotes starch-coated paper samples, F indicates fumarated CWR-coated paper samples, and P indicates fortified and esterified CWR-coated paper samples (more details of the method are given in Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). The captured images’ interphase thickness was measured using the software platform of a Leica Microscope LAS image analyzer. The images were transformed using Adobe Photoshop software to template images. Grid images were created with template images. Each grid represented an interphase thickness measurement.

Each image contains 40 measurements. Three images of the surface treatment were selected randomly. After and before surface treatment with hydrophobic additives, optical images and template images and thickness and interphase thickness of the sample (μm) results are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Optical Microscopy Measurement Results of Samples Treated with Cationic Starch (S), Fumarated CWR Blended Starch (F), and Penta-Ester CWR (P) Blended Starch.

Cobb60 Sizing Results

The paper samples were kept in a conditioning room for 24 h according to ISO 187 before the Cobb60 test was carried out. Results of the Cobb60 tests, evaluated according to ISO 535, are given in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Cobb60 results of the samples.

Due to internal sizing applied to these products, the initial Cobb60 value of the paperboard was 75 ± 2 g/m2, whereas that of the test liner was 86 ± 2 g/m2. The bleached kraft paper absorbed too much water to be able to measure it. Surface treatment with cationic starch reduced the Cobb60 value to 20 and 11% of the values for the default paperboard and test liner base paper specimens. The hydrophobic agent with fumarated CWR (F) added to the surfaces of paperboard, test liner, and bleached kraft paper samples reduced the Cobb60 values to 23, 15, and 27%, respectively, compared to what was achieved with just starch applied to the surface. In addition, the fumarated penta-ester CWR (P) at the same coating weight reduced the Cobb60 value to 45, 48, and 39%, compared to just starch applied to the three types of surfaces. This promises to help achieve better water resistance properties with novel hydrophobic agents obtained by derivatization of wood rosin.

A lower Cobb60 value was obtained when penta-ester CWR (P) was added as a hydrophobic agent. In each case, this showed better resistance to absorption of fluids into the paper. Earlier studies indicated that a decrease in the Cobb60 value after starch treatment on the surface was correlated with the coating weight.18,39,47 Considering the coating weights, a higher desirable decrease of the Cobb60 value was obtained when using fortified and esterified CRW samples than starch-sized linerboard samples.

Water Vapor Transmission Rate

The water vapor resistance value is associated with the continuous nature of the starch film, as well as the hydrophobization of the materials.40 The pinholes decreased through the surface sizing process, thus reducing the water vapor transmission rate, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Water vapor transmission rate results of the samples.

Lower water vapor transmission rates were attained when penta-ester CWR (P) was added as a hydrophobic agent. This implies that the P treatment contributed to better barrier properties, resulting in higher reduction in WVTR. The differences in the chemical modification of rosin products affecting the physical structure of the surface of the paper samples appear to be important for water vapor barrier properties. In previous studies, it has been stated that even if the coating weight of the cooked starch is increased, it does not significantly reduce WVTR.48 This suggested that the slight reduction in values compared to samples coated with starch alone was due to rosin, which contributed to the hydrophobicity of the surface.

Optical Test Results

The surface sizing process affected the optical properties of the paper surface. The sizing application may decrease the whiteness of the paper. High whiteness values are important for typical grades of bleached kraft paper. The color of the base paper affects the appearance of printed paper products.7 Whiteness and brightness values were characterized using an Elrepho spectrophotometer with a D65 illuminant and 10° observer. The values of whiteness of surface sizing-applied base paper are given in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

ISO whiteness values of bleached kraft paper and surface sizing-treated paper.

As shown in Figure 7, fortified and esterified sizing agents exhibited the lowest whiteness values. However, Cobb60 values were improved, i.e., with reduced uptake of water. The relatively low brightness is consistent with the coloration of the unrefined rosin material (CWR) used in the present work.

ISO brightness (%) results after and before surface treatment with hydrophobic additives are listed in Table 3. The results show that there were no important differences in brightness that could be attributed to the presence of hydrophobic additives.

Table 3. Brightness (%) Results of the Samples.

| hydrophobic additives |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| paper type | base | SD | starch | SD | fumarated CWR | SD | penta-ester CWR | SD |

| bleached kraft (BK) | 85.29 | 0.13 | 83.92 | 0.37 | 82.71 | 0.21 | 83.96 | 0.39 |

| white top cartonboard (WTC) | 55.49 | 0.39 | 55.25 | 0.31 | 55.32 | 0.29 | 55.46 | 0.27 |

| test liner (TL) | 23.59 | 0.37 | 22.48 | 0.35 | 22.31 | 0.24 | 22.51 | 0.23 |

Conclusions

Water repellency values were increased when paper specimens had been surface-sized using starch solutions that contained rosin that had been fortified with fumaric acid (CWR) or had been both fortified and then esterified with pentaerythritol. The improved performance was consistent with the increase of molecular weights of the hydrophobic additives. The surface sizing process decreased water vapor permeability. The two rosin derivatives dissolved in ethanol and added to the cationic starch solution were able to improve holdout of the water at the paper surface. Three different paper types were compared relative to the effectiveness of surface treatment. More favorable Cobb60 values, air resistance, and water vapor transmission rates were achieved when using the fortified and esterified CRW samples than the starch-sized linerboard samples. However, the formulations including the rosin derivatives reduced the whiteness to a greater extent. Based on the present work, rosin derivatives used as a surface chemical additive have good prospects for those paper surface applications in which whiteness is not the primary target. It is suggested that the pentaerythritol ester derivative of rosin (P) is more effective as a hydrophobic surface additive.

Acknowledgments

Material support for this research was provided by IVA Rosin Biomass Company (Edremit/Balikesir).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c03610.

Composition of methylated CWR sample determined by GC–MS and list of compounds of methylated CWR (Table S1); detailed surface treatment images (Figure S1); and optical microscopy images of the treated sheets (Figure S2) (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Financial support for this research was provided from TUBITAK (2219, 1059B191801391).

Supplementary Material

References

- Davison R. W. The Sizing of Paper. Tappi 1975, 58, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas D. H. An Overview of Cellulose - Reactive Sizes. Tappi J. 1981, 64, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt S. M.Fundamentals of Sizing with Rosin. TAPPI Notes; Tappi Press, 1987; pp 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts J. C. In Chemical Control of Water Penetration in Paper, First International Conference on Interactive Paper; Guadalajara: Mexico, 1997.

- Neimo L.Internal Sizing of Paper. In Papermaking Science and Technology, Vol. 4. Papermaking Chemistry; Finnish Paper Engineers’ and Tappi Faper Oy: Espoo, Finland, 1999; pp 151–203. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbe M. A. Paper’s Resistance to Wetting - A Review of Internal Sizing Chemicals and Their Effects. BioResources 2006, 2, 106–145. 10.15376/BIORES.2.1.106-145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Zhang F.; Chen F.; Pang Z. Preparation of a Crosslinking Cassava Starch Adhesive and Its Application in Coating Paper. BioResources 2013, 8, 3574–3589. 10.15376/biores.8.3.3574-3589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson L.; Wilhelmsson B.; Stenetröm S. The Diffusion of Water Vapour through Pulp and Paper. Dry. Technol. 1993, 11, 1205–1225. 10.1080/07373939308916896. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samyn P. Wetting and Hydrophobic Modification of Cellulose Surfaces for Paper Applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 6455–6498. 10.1007/s10853-013-7519-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klass C. P. Trends and Developments in Size Press Technology. Tappi J. 1990, 73, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed S. H.; Nagieb Z. A.; Meligy M. G. E. Enhanced Optical, Chemical and Mechanical Properties for Different Cellulosic Fibers Treated by Different Concentrations of Polymers. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 3, 880. [Google Scholar]

- Reid J. G. New Developments in Starch Technology. Pap. Technol. Ind. 2003, 16, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts J. C.; Au C. O.; Clay G. A.; Lough C. A Study of the Effect of Cationic Starch on Dry Strength and Formation Using C14 Labelling. J. Pulp Pap. Sci. 1987, 13, J1–J5. [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. L.; Shin J. Y.; Koh C. H.; Ryu H.; Lee D. J.; Sohn C. Surface Sizing with Cationic Starch: Its Effect on Paper Quality and Papermaking Process. Tappi J. 2002, 1, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi M.; Esmail N.; Garnier G.; van de Ven T. G. M. Starch Penetration into Paper in a Size Press. J. Dispersion Sci. Technol. 2005, 25, 457–468. 10.1081/DIS-200025714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barker L. J.; Proverb R. J.; Brevard W.; Vazquez I. J.; Depierne O. S.; Wasser R. B. In Surface Absorption Characteristics of ASA Paper: Influence of Surface Treatment on Wetting Dynamics of Ink-Jet Ink, Tappi 1994 Papermakers Conference Proceedings, Atlanta, 1994.

- Aloi F.; Trksak R. M.; Mackewicz V. In The Effect of Base Sheet Properties and Wet End Chemistry on Surface-Sized Paper, TAPPI Papermakers Conference, 2001, p 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fineman I.; Hoc M. Surface Properties, Especially Linting, of Surface-Sized Fine Papers – Influence of Starch Distribution and Hydrophobicity. Tappi J. 1978, 61, 433–446. [Google Scholar]

- Latta J. L. In Practical Applications of Styrene Maleic Anhydride Surface Treatment Resins for Fine Paper Sizing, TAPPI 1994 Papermakers Conference, 1994; pp 399–406.

- Rastogi V. K.; Samyn P. Bio-Based Coatings for Paper Applications. Coatings 2015, 5, 887–930. 10.3390/coatings5040887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa H.; Youssef A. M.; Darwish N. A.; Abou-Kandil A. I. Eco-Friendly Polymer Composites for Green Packaging: Future Vision and Challenges. Compos. Part B 2019, 172, 16–25. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.05.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X.; Bian P.; Xue Y.; Qian X.; Yu H.; Chen W.; Hu X.; Wang P.; Wu D.; Duan Q.; Li L.; Shen J.; Ni Y. Combination of Microsized Mineral Particles and Rosin as a Basis for Converting Cellulosic Fibers into “Sticky” Superhydrophobic Paper. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 174, 95–102. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Liu X.; Zhang Q.; Wang B.; Yu C.; Rashid H. U.; Xu Y.; Ma L.; Lai F. Characteristics and Kinetics of Rosin Pentaerythritol Ester via Oxidation Process under Ultraviolet Irradiation. Molecules 2018, 23, 2816 10.3390/molecules23112816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussell W. R.; Morgan S. N. Papersizing Compositions 1993, 5, 363. [Google Scholar]

- Halbrook N.; Lawrence R. Fumaric Modified Rosin. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1958, 50, 321–322. 10.1021/ie50579a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto T. Bio-Based Polymeric Materials from Epoxidized Triglyceride and Rosin Derivatives. Trends Green Chem. 2016, 2, 1–7. 10.21767/2471-9889.100010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heiskanen N.; Jämsä S.; Paajanen L.; Koskimies S. Self-Emulsifying Binders for Water-Borne Coatings-Synthesis and Characteristics of Maleated Alkyd Resins. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2011, 119, 209–218. 10.1002/app.32679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q.; Liu X.; Zhang R.; Zhu J.; Jiang Y. Synthesis and Properties of Full Bio-Based Thermosetting Resins from Rosin Acid and Soybean Oil: The Role of Rosin Acid Derivatives. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 1300–1310. 10.1039/c3gc00095h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiyono B.; Tachibana S.; Tinambunan D. Reaction of Abietic Acid with Maleic Anhydride and Fumaric Acid and Attempts to Find the Fundamental Component of Fortified Rosin. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2007, 10, 1588–1595. 10.3923/pjbs.2007.1588.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gafvert E. Allergic Components in Modified and Unnodified Rosin: Chemical Characterstization and Studies of Allergenic Activity. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 1994, 184, 1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk Othmer.Radioactive Drugs and Tracers to Semiconductors: Natural Resin. In Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology; Wiley, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Panda R.; Panda H. Preparation of Fumaropimaric Acid. Chem. Ind. For. Prod. 1986, 6, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fulzele S. V.; Satturwar P. M.; Dorle A. K. Study of Novel Rosin-Based Biomaterials for Pharmaceutical Coating. AAPS PharmSciTech 2002, 3, 45–51. 10.1208/pt030431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton R. E.; Hamm J.; Langenheim J. H. Plant Resins: Chemistry, Evolution, Ecology, and Ethnobotany. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 2004, 93, 784–785. 10.2307/4129644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karlberg A. T.Colophony: Rosin in Unmodified and Modified Form. Kanerva’s Occupational Dermatology, 2nd ed.; Rustemeyer T.; Elsner P.; John S. M.; Maibach H. I., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, 2012; pp 467–479. [Google Scholar]

- Hardell H. L. Characterization of Impurities in Pulp and Paper Products Using Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry, Including Direct Methylation. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 1993, 27, 73–85. 10.1016/0165-2370(93)80023-S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ping Shao L.; Gäfvert E.; Karlberg A. -T.; Nilsson U.; Nilsson J. L. G. The Allergenicity of Glycerol Esters and Other Esters of Rosin (Colophony). Contact Dermatitis 1993, 28, 229–234. 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1993.tb03408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandermann W.Naturharze Terpentinöl, Tallöl; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj S.; Bhardwaj N. K. Comparison of Polyvinyl Alcohol and Oxidised Starch as Surface Sizing Agents. Appita J. 2018, 7, 321–329. [Google Scholar]

- Bordenave N.; Grelier S.; Coma V. Hydrophobization and Antimicrobial Activity of Chitosan and Paper-Based Packaging Material. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 88–96. 10.1021/bm9009528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krochta J. M.; Baldwin E. A.; Nisperos-Carriedo M. O.. Edible Coatings and Films to Improve Food Quality; CRC Press LLC: Boca Raton, FL, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pine Chemicals Association. Final Submission for Rosins and Rosin Salts, 2004.

- Pinova.Technical data: pexite FF. http://www.pinovasolutions.com/products/.

- OMRI. Technical Evaluation Report: Wood Rosin Handling/Processing, 2014.

- Strazdins E. Mechanistic Aspects of Rosin Sizing. Tappi 1977, 60, 102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Maiti S.; Ray S. S.; Kundu A. K. Rosin: A Renewable Resource for Polymers and Polymer Chemicals. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1989, 14, 297–338. 10.1016/0079-6700(89)90005-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brungardt B. In Improving the Efficiency of Internal and Surface Sizing Agents, 83rd Annual Meeting, Technical Section, Canadian Pulp and Paper Association, Preprints, 1997; pp B109–B112.

- Spence K. L.; Venditti R. A.; Rojas O. J.; Pawlak J. J.; Hubbe M. A. Water Vapor Barrier Properties of Coated and Filled Microfibrillated Cellulose Composite Films. BioResources 2011, 6, 4370–4388. 10.15376/biores.6.4.4370-4388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.