Abstract

The development of high-efficiency and low-cost new catalysts is an extremely attractive topic. In this study, two different matrix bentonite-modified fly ash catalysts were successfully prepared, and the compressive strength of the catalyst was studied by using unsaturated dynamic and static triaxial technology. The axial compressive strength of FC (fly ash catalysts added with Ca-based bentonite) was greater than that of FN (fly ash catalysts added with Na-based bentonite). The catalyst reached 978 kPa. The prepared catalyst was characterized by X-ray diffraction analysis, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and specific surface area analysis (BET) of the catalyst. In addition, denitration performance of different catalysts was explored, and the reaction conditions were optimized. The results demonstrate that when the mixing ratio of fly ash and calcium-based bentonite in the FC is 4:1, the compressive strength is relatively high, and the denitration rate reaches about 82%.

1. Introduction

Every year, up to 600 million tons of fly ash are emitted by China and costs a lot to deal with. Fly ash is a type of cheap industrial solid waste, and the accumulation of it will cause a large amount of arable land and farmland to be occupied.1−3 The erosion of rain will pollute groundwater, and the dust generated by wind will endanger people’s health.4 Fly ash is a byproduct of coal combustion in coal-fired power plants with a good pore structure, which is widely used in ecological sewage treatment, industrial catalyst preparation, and soil remediation. Unfortunately, industrial catalysts prepared with fly ash often cause insufficient strength and hardness in the process of flue gas denitration.5−8 They are easily blown away under the action of high-speed airflow and are conducted by airflow, leading to secondary pollution.9,10 Fly ash tends to pulverize when it meets water vapor. Therefore, it is of great significance to develop denitration catalysts with high strength, good stability, and low cost.11

The strength of the catalyst is mainly affected by the basic physical properties of the powder and additives.12 Most of the solid catalysts or supports exist in the form of some powder materials before the molding process, so the molding of the catalyst mainly depends on the basic physical properties of the powder materials.13 In fact, the powder molding process is a complicated combination of the shape, particle size, particle size distribution, density, pore structure, fluidity, and other physical properties of the powder material.14 Catalyst molding methods are mainly composed of the following four processes: compression, extrusion molding method, rotational molding method, and spray molding method.15 In particular, the extrusion molding method is also a widely used catalyst molding process.16 It mainly combines catalyst powder and a certain amount of water with extra additives. After fully mixing, the mixed materials are sent to the extrusion machine, selecting different molds according to the need, and then cutting the extrudate into a certain length of product to obtain the catalyst molded product.17−19 Extrusion molding usually includes four steps: raw material conveying, compression, extrusion, and cutting.20 During the extrusion process, the properties of the mud and the choice of the molding binder have a significant influence on the stability of the extrusion molding catalyst.21

Bentonite is a commonly used nonmetallic mineral. Bentonite can absorb 5 times its own weight in water22 because the unit cell particles are not large and the surface is broad, irregular, and charged. Expansive soil is evenly mixed with fly ash and aqueous solution and then blended together.23−25 During the extrusion molding process, the stability of the extruded catalyst is greatly ensured, and the change of the catalyst form is prevented.26 So far, proven cumulative reserves have exceeded 5.087 billion tons, and the unreserved reserves are expected to exceed 7 billion tons. Compared with other types of binders, the catalyst prepared by adding bentonite to fly ash has high strength and low cost.27−29 This method provides a new way to prepare denitration catalysts with extraordinary strength, high stability, and low cost.30

This article explains for the first time that bentonite is used as a matrix binder to add to fly ash to prepare a denitration catalyst with high strength and low cost and that does not easily pulverize. First, a denitration catalyst was successfully prepared by using fly ash and bentonite as raw materials. The prepared catalyst was characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis, Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and specific surface area analysis of the catalyst. The mechanical properties and the denitration performance of the catalyst have been studied. The results show that the catalyst prepared with the bentonite matrix binder has a great strength. In addition, the catalyst has a relatively safe removal effect on nitrogen oxides in flue gas under different conditions. Therefore, this research is of great significance to the search for a denitration catalyst with high strength and low cost and also provides theoretical support for better low-cost denitration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of the Catalyst

The fly ash used in the experiment came from the Datang Power Plant in Gongyi City, Henan Province, and bentonite was produced by Tianyuan Non-metallic Products Co., Ltd. without further purification. Our research has mainly completed the shaping and screening of different matrix bentonite-modified fly ash catalysts. Taking the modified fly ash catalyst process with different additional amounts of Ca-based bentonite as an example, the preparation of other matrix catalysts is carried out similar to that of Ca-based ones. In this typical experiment, Ca-based bentonite and Na bentonite were mixed with fly ash at a mass ratio of 4:1, and the dry materials were put into a six-joint mixer for low-speed dry mixing for 10 min. Then, deionized water was added to the dry materials at a water-to-powder ratio of 14% and evenly mixed, using a six-joint mixer to fully mix the wet and dry materials for 30 min and scale them for 24 h. Then, the stale mud block was put into the mud mixer and stirred for 30 min, putting the mixed mud block into the catalyst-forming machine for extrusion molding and cutting into a catalyst with a length of 1 cm. Then, it is put into the drying box for drying at 65 °C for 0.5 h. The equal volume dipping method was used. The Mn loading amount was selected to be 8%. The catalyst was soaked in manganese nitrate solution for 24 h and then taken out and put in a drying box for drying at 65 °C for 1 h. Then, it was put in a furnace. In the furnace, the temperature was increased to 450 °C at a rate of 50 °C/min for 2 h. Finally, a fly ash catalyst with Ca-based bentonite and Na-based bentonite as a binder is prepared. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the catalyst preparation process.

2.2. Evaluation Device of the Catalyst

2.2.1. Evaluation of Catalyst Strength

Strength determination is an important indicator of the catalyst. Besides the heat resistance and sufficient activity, it must also guarantee the strength to resist external forces. In industry, catalyst wear is complex and diverse, including handling wear and packing shock wear as well as filling extrusion wear and air impact wear. In order to ensure that it is not pulverized, lost, or crushed in the fixed bed reaction, the strength can be increased to withstand a large amount of filling. The test adopts axial force uniformly until it is broken. In this experiment, a three-axis saturator was used for test block demolding, with a height of 80 mm and a diameter of 39.1 mm. The LO7010/5/DYN-type unsaturated dynamic and static triaxial instrument was used to carry out the pressure resistance test on the catalyst, and all the tests are automatically run and calculated by the computer.

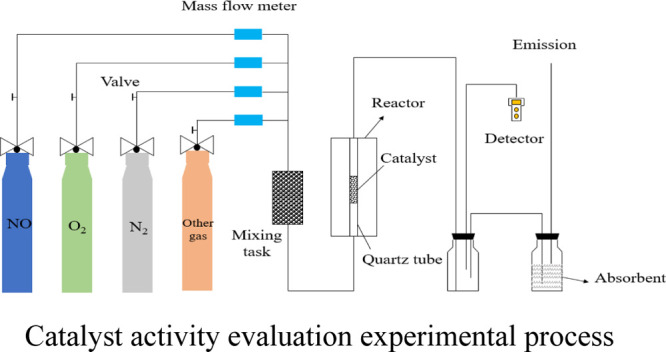

2.2.2. Activity Evaluation of the Catalyst

In this study, the denitration performance of the catalyst was evaluated in a simulated flue gas system at a constant temperature of 150 °C. The tube furnace is equipped with 12 g of catalyst, of which NO, N2, and O2 are the simulated flue gas and NH3 is the reducing gas. The intake air volume of O2 is 60 mL/min, the intake concentration of NO is 600 ppm, the intake concentration of NH3 is 600 ppm, and N2 is used as the filling gas. The gas enters the mixed gas tank after passing through the flow meter and enters the simulated flue gas system for testing after being completely mixed. By adopting a Testo 340 flue gas analyzer to detect the flue gas outlet concentration, the test process is carried out and shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Catalyst activity evaluation experimental process.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mechanical Properties

3.1.1. Composition Analysis

It can be seen from Table 1 that the content of CaO in Ca-based bentonite is higher than the content of CaO in Na-based bentonite, while the content of Na2O in Na-based bentonite is higher than that in Ca-based bentonite. In addition, the remaining element composition is basically the same. Some literature studies indicate that the alkali metal on the catalyst surface will have an adverse effect on the acidic sites and inhibit the adsorption of alkaline gases such as NH3 on the acidic sites. The greater the alkali metal content in the catalyst is, the stronger the alkali metal’s inhibitory effect on the acid sites on the catalyst surface will be. Therefore, the ability of the catalyst to adsorb alkaline gases such as NH3 will be weakened, which will affect the catalyst’s conversion rate of nitrogen oxides (Du et al. 2017). Studies have shown that the acidic site playing a significant role in the low-temperature denitration reaction is Bronsted, so the alkali metal has a greater impact on the performance of the low-temperature denitration catalyst.31−33 Studies have shown that different kinds of alkali metals have different inhibitory effects on catalyst performance, which are mainly related to the alkalinity of alkali metals.34 The greater the alkalinity is, the more obvious the inhibition of alkali metals will be, and the order of inhibition is as follows: K > Na > Ca > Mg. This can also explain the reason why Ca-based bentonite is better than Na-based bentonite in denitration.

Table 1. Content of Oxides in Fly Ash.

| species | Al2O3 | SiO2 | CaO | Fe | Na2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fly ash (%) | 24.20 | 45.10 | 5.60 | 0.85 | 0.02 |

| Ca-based bentonite (%) | 15.44 | 68.10 | 0.77 | 0.33 | 0.02 |

| Na-based bentonite (%) | 16.43 | 68.50 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

3.1.2. Compressive Strength

An unsaturated dynamic and static triaxial instrument was used to assess the axial compressive strength curves of bentonite as the matrix binder and pure fly ash as the catalyst. As shown in Table 2, the axial compressive strength of the catalyst prepared from fly ash is 135 kPa, and the compressive strengths of Ca-based bentonite and Na-based bentonite are 978 and 721 kPa, respectively, which indicate that the pulverized fly ash as a catalyst has low compressive strength, so it needs to be appropriately improved. After adding certain amount of bentonite to fly ash, an ion-exchange and hardening reaction occurs between fly ash and bentonite. High-valent cations such as calcium ions, aluminum ions, and iron ions in fly ash replace low-valent cations in bentonite. At the same time, components such as silica and alumina contained in fly ash react with bentonite to form gel components such as calcium silicate and calcium aluminate hydrate. These ion-exchange and hardening reactions cause the expansive soil particles to agglomerate and thicken and weaken the expansion and contraction effect of the expansive soil. In industries, the amount of catalyst used is expected to be very large. In order to make sure it is not pulverized, lost, or crushed in the fixed bed reaction, the catalyst needs to have high strength so that it can withstand a large amount of filling. During the molding process of the catalyst, the bentonite can be dispersed between the fly ash particles under the action of water and after drying and roasting. The bentonite between the fly ash particles forms a skeleton structure with it. As a matrix binder, it supports the fly ash. Bentonite has a high decomposition temperature and can also play a framework role in the catalyst reaction process, making the catalyst strong.

Table 2. Strength of Catalysts Made from Different Types of Bentonite.

| different material catalyst | F | FC | FN |

| axial compressive strength (kPa) | 135 | 978 | 721 |

It can be seen from Figure 3 that the intensities of 2:1, 3:1, and 4:1 are high and do not change significantly in this range. Due to the cost limitation of the catalyst, the costs of the catalyst of 2:1 and 3:1 are relatively high, which is not suitable for manufacturing efficient and low-cost catalysts. Therefore, the denitration test chose a 4:1 catalyst with higher strength and lower preparation cost.

Figure 3.

Effect of different ratios of bentonite addition on catalyst strength.

3.2. Microstructure Characterization

3.2.1. XRD Analysis

The green line in Figure 4 is the XRD pattern of fly ash. According to the PDF # 15-0776 card of mullite, it can be seen that the characteristic peaks of the mullite crystal form appear at angles of 16.43 and 26.27, 33.23, 35.28, 40.87, and 60.71°. The characteristic peaks of quartz crystal appear at 23.02, 30.92, and 52.62°. The main components of mullite are silica and alumina, which are columnar or needle-shaped crystals of high-temperature resistant silicate minerals. The main component of quartzite is silica. It can be concluded that the main components of fly ash are silica and alumina. The red and black lines in Figure 4 are the XRD patterns of FC (fly ash catalysts added with calcium bentonite) and FN (fly ash catalysts added with sodium bentonite). The characteristic peaks of the quartz crystals of the two bentonites all appeared at 23.02, 30.92, and 52.62°. The main components of mullite are silica and alumina. It is a high-temperature silicate mineral that forms columnar or needle-like crystals. It can be seen from the figure that there is no obvious difference between the diffraction peaks of the fly ash catalyst doped with different bentonite.

Figure 4.

XRD of different types of bentonite.

3.2.2. FT-IR Spectroscopy

It can be seen from the green line in Figure 5 that the Si–O vibration peak of the fly ash raw material appears near 1100 cm–1, while the Al–O vibration peak of AlO6 appears near 560 cm–1. These tensile vibration peaks are all related to mullite, an important component in fly ash. The vibration peak near 1600 cm–1 is attributed to the adsorption peak of carbon-based functional groups, while the vibration peak near 2875–3000 cm–1 is the characteristic peak of OH functional group stretching vibration on the surface of alcohols, carboxylic acids, phenols, and ethanol.

Figure 5.

FT-IR of different dopant catalysts and fly ash.

From the red and black lines in Figure 5, it can be seen that both FC (fly ash catalysts added with calcium bentonite) and FN (fly ash catalysts added with sodium bentonite) have a H–C–H tensile vibration peak at 1469 cm–1. The second is the Si–O–Si skeleton vibration peak near 1100 cm–1, and 600–400 cm–1 is the internal vibration of the silicon–oxygen tetrahedron and the aluminum–oxygen octahedron. The infrared spectra of the fly ash catalyst doped with two kinds of bentonite are basically similar, and both have characteristic peaks of bentonite. The C≡C and C≡N tensile vibration peaks appearing at 2360–2332 cm–1 are totally different. This shows that the structures of these two substances are quite different. The absorption peak has a certain shift, indicating that the cations between the silicate sheets are changed, which changes the distribution of the silicate structural force. The acidic functional groups (carbon groups and phenolic hydroxyl groups) of Ca-based bentonite have a positive effect and improve the adsorption capacity of the catalyst for alkaline gas NH3.

3.2.3. Scanning Electron Microscope

The surface morphology of fly ash is shown in Figure 6. Figure 6a,b shows images magnified 1000 times and 5000 times, respectively. It can be obviously seen that the fly ash is mainly in a small spherical shape after being enlarged, and the surface is relatively smooth. Some spheres have tiny crystals, the main component of which is mullite, and these particles are formed by rapid cooling of ash particles calcined at high temperatures. From Figure 6b, we can note that the size of the spherical particles of fly ash is different. The spherical particles are not closely connected, but there are large gaps. Figure 6c–f shows images of Ca-based bentonite and Na-based bentonite magnified by 1000 times and 5000 times, respectively. It can be observed that the morphological characteristics of the two kinds of bentonite are relatively similar. The surface consists of many tiny particles, and these particles have a scaly dissociated morphology, and the porous structure of the Ca-based graph particles is more abundant, which makes Ca-based bentonite have larger specific surface area. Figure 6e,f shows SEM images of Ca-based bentonite magnified 1000 times and 5000 times, respectively. Figure 6g,h shows SEM images of the fly ash catalyst doped with Ca-based bentonite, magnified 1000 times and 5000 times, respectively. Compared with Figure 6e,f, it can be seen that under the premise of using fly ash as the matrix, calcium-based bentonite is added to bind fly ash particles. Calcium bentonite is calcined at high temperatures to form the framework of the catalyst, thereby improving the strength of the catalyst effectively. It can be clearly seen from Figure 6h that there are still a large number of voids in the fly ash catalyst mixed with Ca-based bentonite, which provides a good active center for subsequent use as a denitration catalyst.

Figure 6.

(a–h) Catalyst SEM of different magnifications.

3.2.4. Specific Surface Area Analysis (BET)

The results of specific surface area measurement of different types of bentonite catalysts are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Specific Surface Area of Different Catalysts.

| catalyst | total pore volume of micropores (cm3/g) | single point adsorption total pore volume (cm3/g) | adsorption average pore size (nm) | specific surface area (m2/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | 0.004 | 0.044 | 15.203 | 10.680 |

| FC | 0.005 | 0.045 | 12.243 | 16.996 |

| FN | 0.005 | 0.047 | 13.503 | 13.851 |

Analysis of Table 3 shows that the specific surface area of the FC (fly ash catalysts added with Ca-based bentonite) is larger than that of the FN (fly ash catalysts added with Na-based bentonite), and the specific surface area of only the fly ash catalyst F (pure fly ash catalyst) is the smallest. The specific surface area is not very large, so the denitration effect does not basically depend on the specific surface area but mainly depends on the active sites on the catalyst, that is, the active center. The more the active centers are, the stronger the catalytic activity is, and it generally shows a positive correlation.

The results of specific surface area measurement of different bentonite addition ratios are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Specific Surface Area of Catalysts with Different Bentonite Addition Ratios.

| bentonite addition amount | total pore volume of micropores (cm3/g) | single point adsorption total pore volume (cm3/g) | adsorption average pore size (nm) | specific surface area (m2/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3:1 | 0.004 | 0.051 | 17.347 | 16.467 |

| 4:1 | 0.004 | 0.049 | 16.820 | 14.996 |

| 5:1 | 0.005 | 0.042 | 16.338 | 12.139 |

| 6:1 | 0.004 | 0.046 | 15.740 | 11.692 |

It can be seen from Table 4 that as the proportion of doped bentonite increases, the specific surface area of the corresponding catalyst gradually decreases. The average pore size of adsorption and the total pore volume of single point adsorption also showed a decreasing trend. The total pore volume of micropores changes slightly. On the one hand, during the loading process, MnO2 enters the bentonite interlayer during the process of compounding with the catalyst to increase the specific surface area; on the other hand, the bentonite in the catalyst slurry before roasting contains a large amount of interlayer water. During the calcination of the catalyst, a large amount of water between the layers evaporates, leaving voids in the catalyst. The interlayer hydrated calcium ions and the structural water in the Al2O3 crystallites in the bentonite decrease, and the number of voids in the catalyst increases, leading to an increase in its surface area. The larger the specific surface area of the catalyst is, the more beneficial it is to increase the activity of the catalyst and the dispersion of active components. The reactants NOX and the product N2 easily enter and exit the inner pores of the catalyst, and the catalyst activity of the denitration reaction is improved. However, as the amount of doped bentonite grows, the sodium and potassium content in the catalyst also increases, which causes the metal to poison the active component MnO2 on the catalyst surface and reduces the denitration efficiency.

3.3. Impact of Denitration Performance

3.3.1. Effect of Adding Different Types of Bentonite on Catalytic Performance

The following ways are used to compare the denitration effects of different bentonite catalysts. First, 3 g of pure fly ash catalyst (F), fly ash catalyst (FC) added with Ca-based bentonite, and fly ash catalyst (FN) added with Na-based bentonite were weighed. Second, the simulated flue gas system is utilized to carry out denitration experiments and screen out the best bentonite types.

It can be seen from Figure 7 that the denitration performance of the FC (fly ash catalyst added with Ca-based bentonite) is generally better than that of the FN (fly ash catalyst added with Na-based bentonite) , and the F (pure fly ash catalyst) has the lowest denitration rate. It can be seen from the inset of Figure 7 that the removal of NO by FC is significantly higher than that of F and FN. The reason for the analysis is that when bentonite is added, the specific surface area and pore volume of the catalyst are increased, and the dispersion of the active component MnO2 is greater. The reactant NOX and the product N2 easily enter and exit the inner pores of the catalyst, which improves the catalyst activity of the denitration reaction. It is pointed out in the literature that the active components in bentonite expand the specific surface area in the form of a column support and optimize the oxidation–reduction characteristics of the catalyst surface.35 Combined with the axial compressive strength, the optimal bentonite type determined by the experiment is Ca-based bentonite.

Figure 7.

Denitration rates of different types of bentonite.

3.3.2. Influence of Adding Different Ca-Based Bentonite on Catalytic Performance

In order to compare the denitration effects of different bentonite catalysts, 3 g of catalyst with mass ratios of fly ash and bentonite of 3:1, 4:1, 5:1, and 6:1 was weighed and put into a simulated flue gas system for denitration to screen out the best addition amount of bentonite. The specific results are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Effect of different addition amount of bentonite on denitration rate.

It can be seen from Figure 8 that the catalyst with a mass ratio of fly ash and bentonite of 4:1 is better than the catalyst with a mass ratio of fly ash and bentonite of 3:1, 5:1, and 6:1. It can be seen from the inset in Figure 8 that the removal amount of NO by FC is 1180 μg, which is higher than the other three proportions. Because a small amount of doped bentonite has a strong adsorption capacity, it is conducive to the adsorption of NH3 and other reactants on the surface of the catalyst, which also improves the denitration activity of the catalyst. When the doping amount of bentonite further increases, the alkali metal in the bentonite becomes more. Studies have pointed out that the introduction of an alkali metal will inhibit the adsorption of NH3 at the Bronsted acidic sites, and the inhibition of ammonia adsorption will increase with the growth of alkali metal doping. The deposition of alkali metals and alkaline earth metals on the catalyst surface will reduce the number of Bronsted acid sites and acid strength, thereby inhibiting the activity of the catalyst.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, fly ash is selected as the catalyst research carrier. The properties of fly ash and the compressive strength of the F single catalyst and FC (fly ash catalysts added with Ca-based bentonite) and FN (fly ash catalysts added with Na-based bentonite) composite catalysts are investigated. Besides, screening out the best bentonite types and adding an amount of bentonite for composite catalysts and exploring the denitration performance were carried out. The results show that the axial compressive strength of FC is greater than that of FN, reaching 978 kPa. The principal components of pulverized coal selected in the experiment are Al2O3 and SiO2, which are spherical in shape after magnification. After adding Ca-based bentonite, the small spherical fly ash is tied together, and the strength of the formed catalyst is effectively improved. The surface of FC (fly ash catalysts added with Ca-based bentonite) contains more acidic functional groups, which enhance its NH3 adsorption capacity and promote the denitration reaction. Meanwhile, the alkali metal in FN (fly ash catalysts added with Na-based bentonite) has a certain inhibition effect on the catalytic activity of the catalyst, so that its performance is better than that of FN (fly ash catalysts added with Na-based bentonite). When the ratio of fly ash and calcium bentonite in FC (fly ash catalysts added with Ca-based bentonite) is 4:1, the compressive strength ratio is high, and the denitration efficiency is about 82%.

Acknowledgments

Project 51704230 supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China; the Key Laboratory of Coal Resources Exploration and Comprehensive Utilization, Ministry of Natural Resources in P. R. China (KF2019-7); the 2019 Scientific Research Plan by the Geological Research Institute for Coal Green Mining of Xi’an University of Science and Technology (MTy2019-16); the Shaanxi Key Research and Development Project (2019ZDLSF05-05-01); the 2019 Shaanxi Provincial Natural Science Basic Research Program Enterprise Joint Fund Project (2019JL-01); and Project 41602359 supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Zhang Lei(F) and Zhang Lei(M); methodology, Q.L.; software, J.Y. and Y.C.; validation; investigation, Zhang Lei(M); data curation, S.H.; writing-original draft preparation, Q.L.; writing-review and editing, Q.L.; article language checking and editing, B.F. and S.Z.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Wang N.; Xu H.; Li S. A microwave-activated coal fly ash catalyst for the oxidative elimination of organic pollutants in a Fenton-like process. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 7747–7756. 10.1039/C9RA00875F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzić A.; Pezo L.; Mijatović N.; Stojanović J.; Kragović M.; Miličić L.; Andrić L. The effect of alternations in mineral additives (zeolite, bentonite, fly ash) on physico-chemical behavior of Portland cement based binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 180, 199–210. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X.; Jin B.; Cao S.; Ding Q.; Wei Y.; Chen T. CO co-methanation over coal combustion fly ash supported Ni-Re bimetallic catalyst: Transformation from hazardous to high value-added products. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 396, 122668. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshir U. G.; Kande S. R.; Muley G. G.; Gambhire A. B. Synthesis and characterization of Co-Doped fly ash catalyst for chalcone synthesis. Asian J. Chem. 2019, 31, 2165–2172. 10.14233/ajchem.2019.22053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Volli V.; Purkait M. K.; Shu C.-M. Preparation and characterization of animal bone powder impregnated fly ash catalyst for transesterification. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 669, 314–321. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang D.; Li X.; Lv Y.; Zhou M.; He C.; Jiang W.; Liu Z.; Li C. Utilization of limestone powder and fly ash in blended cement: Rheology, strength and hydration characteristics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 232, 117228. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.; Zhang J.; Liu J.; He Y.; Evrendilek F.; Buyukada M.; Xie W.; Sun S. Co-pyrolytic mechanisms, kinetics, emissions and products of biomass and sewage sludge in N2, CO2 and mixed atmospheres. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 397, 125372. 10.1016/j.cej.2020.125372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Li Y.; Song Q.; Liu S.; Yan J.; Ma Q.; Ma L.; Shu X. Investigation on the thermal behavior characteristics and products composition of four pulverized coals: Its potential applications in coal cleaning. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 23620–23638. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.07.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Wen X.; Kong T.; Zhang L.; Gao L.; Miao L.; Li Y.-h. Preparation and mechanism research of Ni-Co supported catalyst on hydrogen production from coal pyrolysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9818–9823. 10.1038/s41598-019-44271-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A.; Hu X.; Lam F. L.-Y. Modified coal fly ash waste as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst for dehydration of xylose to furfural in biphasic medium. Fuel 2019, 239, 726–736. 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.10.138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helwani Z.; Fatra W.; Saputra E.; Maulana R. Preparation of CaO/Fly ash as a catalyst inhibitor for transesterification process off palm oil in biodiesel production. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 334, 012077. 10.1088/1757-899X/334/1/012077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Z.; Yang J.; Lei Z.; Huibin H.; Chao Y.; Min L.; Lintian M. Preparation of soybean oil factory sludge catalyst by plasma and the kinetics of selective catalytic oxidation denitrification reaction. J. Cleaner Prod. 2019, 217, 317–323. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Astuti W.; Chafidz A.; Wahyuni E. T.; Prasetya A.; Bendiyasa I. M.; Abasaeed A. E. Methyl violet dye removal using coal fly ash (CFA) as a dual sites adsorbent. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103262. 10.1016/j.jece.2019.103262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song Q.; Zhao H.; Jia J.; Yang L.; Lv W.; Bao J.; Shu X.; Gu Q.; Zhang P. Pyrolysis of municipal solid waste with iron-based additives: A study on the kinetic, product distribution and catalytic mechanisms. J. Cleaner Prod. 2020, 258, 120682. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chartpuk P.; Chaimahapuk C. Analysis of stress distribution for powder compression molding by finite element method. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2019, 891, 269–274. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.891.269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Z.; Hao S.; Yang J.; Lei Z.; Dan X. Study on Solid Waste Pyrolysis Coke Catalyst for Catalytic Cracking of Coal Tar. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 19280–19290. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.05.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Z.; Jihao J. H.; Zhang L.; Huibin H.; Yusu W.; Yonghui L. Preparation of soybean oil factory sludge catalyst and its application in selective catalytic oxidation denitration process. J. Cleaner Prod. 2019, 225, 220–226. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.03.254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sha F.; Li S.; Liu R.; Li Z.; Zhang Q. Experimental study on performance of cement-based grouts admixed with fly ash, bentonite, superplasticizer and water glass. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 161, 282–291. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.11.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Xiao C.; Wu H.-N.; Kang X. Reuse of Excavated clayey silt in cement–fly ash–bentonite hybrid back-fill grouting during shield tunneling. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1017–1028. 10.3390/su12031017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Z.; Gao H.; Chang X.; Zhang L.; Wen X.; Wang Y. An application of green surfactant synergistically metal supported cordierite catalyst in denitration of selective catalytic oxidation. J. Cleaner Prod. 2020, 249, 119307. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Z.; Hao S.; Lei Z.; Yang J. Gas modified pyrolysis coke for in-situ catalytic cracking of coal tar. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 14911–14923. 10.1021/acsomega.0c00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambuchova M.; Pytlik D. Research of siliceous fly ash after denitrification utilisation in ternary binders. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 385, 012003. 10.1088/1757-899X/385/1/012003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Wen X.; Zhang L.; Sha X.; Wang Y.; Chen J.; Luo M.; Li Y. Study on the preparation of plasma-modified fly ash catalyst and its De–NOX mechanism. Materials 2018, 11, 1047–1062. 10.3390/ma11061047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi K.; Xie J.; Mei D.; He F.; Fang D. The utilization of fly ash-MnOx/FA catalysts for NOx removal. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 065526. 10.1088/2053-1591/aacd8e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patil B. S.; Cherkasov N.; Lang J.; Ibhadon A. O.; Hessel V.; Wang Q. Low temperature plasma-catalytic NOx synthesis in a packed DBD reactor: Effect of support materials and supported active metal oxides. Appl. Catal., B 2016, 194, 123–133. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.04.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ain Q. U.; Rasheed U.; Yaseen M.; Zhang H.; Tong Z. Superior dye degradation and adsorption capability of polydopamine modified Fe3O4-pillared bentonite composite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 397, 122758. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Z.; Yang J.; Hao S.; Lei Z.; Xin W.; Min L.; Yusu W. S.; Dan X. Application of surfactant-modified cordierite-based catalysts in denitration process. Fuel 2020, 268, 117242. 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enquan Z.; Yuhua M.; Munire A.; Zhi S. Adsorption-enrichment and localized-photodegradation of bentonite-supported red phosphorus composites. J. Inorg. Mater. 2020, 35, 803–808. 10.15541/jim20190411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Wang H.; Wang Z.; Qu Z. Adsorption and surface reaction pathway of NH3 selective catalytic oxidation over different Cu-Ce-Zr catalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 447, 40–48. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.03.220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Sun G.; Liu J.; Evrendilek F.; Buyukada M. Co-combustion of textile dyeing sludge with cattle manure:Assessment of thermal behavior, gaseous products, and ash Characteristics. J. Cleaner Prod. 2020, 253, 119950. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zha K.; Kang L.; Feng C.; Han L.; Li H.; Yan T.; Maitarad P.; Shi L.; Zhang D. Improved NOx reduction in the presence of alkali metals by using hollandite Mn-Ti oxide promoted Cu-SAPO-34 catalysts. Environ. Sci.: Nano 2018, 5, 1408–1419. 10.1039/c8en00226f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du X.; Yang G.; Chen Y.; Ran J.; Zhang L. The different poisoning behaviors of various alkali metal containing compounds on SCR catalyst. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 392, 162–168. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.09.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L.; Gu Y.; Han L.; Wang P.; Li H.; Yan T.; Kuboon S.; Shi L.; Zhang D. Dual Promotional Effects of TiO2-Decorated Acid-Treated MnOx Octahedral Molecular Sieve Catalysts for Alkali-Resistant Reduction of NOx. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 11507–11517. 10.1021/acsami.9b01291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C.; Chen Z.; Pang L.; Ming S.; Dong C.; Brou Albert K.; Liu P.; Wang J.; Zhu D.; Chen H.; Li T. Steam and alkali resistant Cu-SSZ-13 catalyst for the selective catalytic reduction of NOx in diesel exhaust. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 344–354. 10.1016/j.cej.2017.09.181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.; Huang T.; Dong L.; Su T.; Li B.; Luo X.; Xie X.; Qin Z.; Xu C.; Ji H. Mn Modified Ni/Bentonite for CO2 Methanation. Catalysts 2018, 8, 646. 10.3390/catal8120646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]