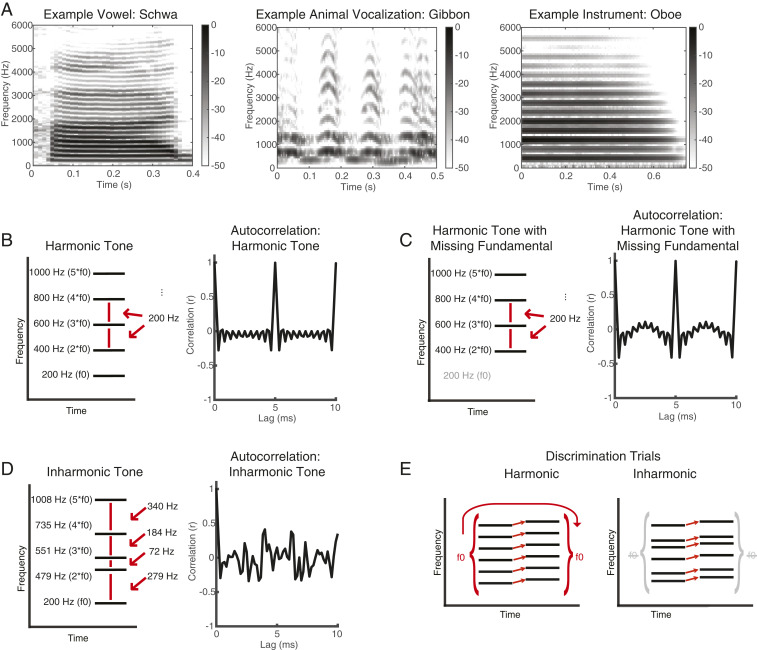

Fig. 1.

Example harmonic and inharmonic sounds and discrimination trials. (A) Example spectrograms for natural harmonic sounds, including a spoken vowel, the call of a gibbon monkey, and a note played on an oboe. The components of such sounds have frequencies that are multiples of an f0, and as a result are regularly spaced across the spectrum. (B) Schematic spectrogram (Left) of a harmonic tone with an f0 of 200 Hz along with its autocorrelation function (Right). The autocorrelation has a value of 1 at a time lag corresponding to the period of the tone (1/f0 = 5 ms). (C) Schematic spectrogram (Left) of a harmonic tone (f0 of 200 Hz) missing its fundamental frequency, along with its autocorrelation function (Right). The autocorrelation still has a value of 1 at a time lag of 5 ms, because the tone has the period of 200 Hz, even though this frequency is not present in its spectrum. (D) Schematic spectrogram (Left) of an inharmonic tone along with its autocorrelation function (Right). The tone was generated by perturbing the frequencies of the harmonics of 200 Hz, such that the frequencies are not integer multiples of any single f0 in the range of audible pitch. Accordingly, the autocorrelation does not exhibit any strong peak. (E) Schematic of trials in a discrimination task in which listeners must judge which of two tones is higher. For harmonic tones, listeners could compare f0 estimates for the two tones or follow the spectrum. The inharmonic tones cannot be summarized with f0s, but listeners could compare the spectra of the tones to determine which is higher.