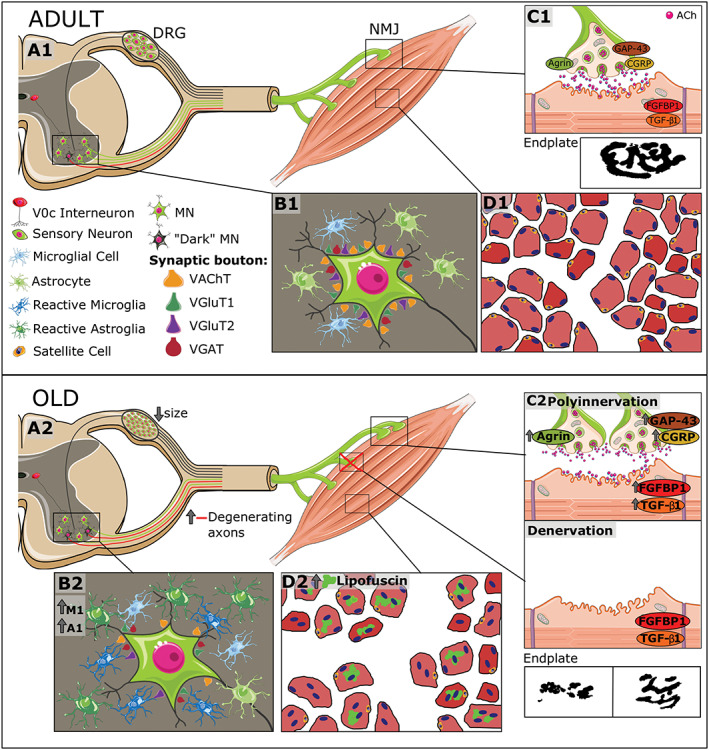

Figure 13.

Overview of age‐associated changes in the mouse neuromuscular system. (A1–D1) The structural organization of the different components of the system, including spinal cord motoneurons (MNs), neuromuscular junctions (NMJs), skeletal muscles, and dorsal root ganglion (DRG) sensory neurons, is schematically represented. MNs, located in the ventral horn, project their axons throughout the ventral roots; motor nerve terminals establish synaptic contacts with skeletal muscle fibres (NMJs). (B1) In normal conditions, adult spinal MNs receive abundant synaptic inputs (synaptic boutons), which can be identified by means of vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) (excitatory cholinergic), vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGluT1) and vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (VGluT2) (excitatory glutamatergic), and vesicular GABA transporter VGAT (inhibitory GABAergic) markers. (A1) Glutamatergic (VGluT1‐positive) afferents to MNs come from proprioceptive (parvalbumin‐positive) sensory neurons located in the DRG; cholinergic afferents (C‐boutons) to MNs come from a small cluster of cholinergic interneurons (V0C), which are located near the central canal of spinal cord. (B1) Spinal MNs are surrounded by abundant microglial and astroglial cells, which are in a resting state. The vast majority of MNs show a ‘healthy’, lightly haematoxylin and eosin‐stained appearance; intermixed with them, some abnormally dark MNs can be occasionally seen in adult spinal cords; these dark MNs could account for the presence of some degenerating motor axons that can be already observed in ventral roots of adult mice. In adult muscles, both presynaptic and postsynaptic elements of NMJs exhibit a well‐organized and ‘healthy’ appearance: smooth nerve terminals enter in endplates displaying a ‘pretzel‐like’ pattern; (C1) adult NMJs exhibited low levels of agrin, growth associated protein 43 (GAP‐43), calcitonin gene‐related peptide (CGRP), fibroblast growth factor binding protein 1 (FGFBP1), and transforming growth factor‐β1 (TGFβ1). (D1) Diagram of adult myofibers surrounded by connective tissue as can be seen in a transverse muscle section. (A2–D2) In the course of ageing, there is (i) an increase in the number of dark MNs; (ii) a reactive gliosis in ventral horn with a raise in the proportion of harmful M1 microglia and A1 astroglia; (iii) a marked loss of excitatory (cholinergic and glutamatergic) synaptic afferents and reduction in the size of GABAergic synaptic boutons on MNs; (iv) an increase in the proportion of degenerated motor axons and the existence of signs of nerve sprouting and regeneration; and (A2 and B2) (v) an atrophy of sensory proprioceptive and nociceptive DRG neurons and increased expression of their markers. (C2) Muscles of old mice exhibit signs of either polyinnervation or denervation and fragmentation of endplates; these changes are accompanied by the increased expression of agrin, GAP‐43, CGRP, FGFBP1, and TGF‐β1, suggesting and active process of NMJ remodelling and muscle reinnervation. Moreover, old muscles show numerous fibres with lipofuscin accumulation and centrally positioned nuclei, indicative of muscle regeneration, and fibrotic tissue deposition between fibres; (D2) the proportion of satellite cells were also markedly reduced in old muscles.