Abstract

Purpose:

Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in men in the US. Since 2015, landmark studies have demonstrated improved survival outcomes with the use of docetaxel (DCT) or abiraterone (AA) in addition to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in the metastatic hormone-naïve setting. These treatment strategies have not been prospectively compared but have similar overall survival benefits despite differing mechanisms of action, toxicity, and cost. We performed a cost-effectiveness analysis to provide insight into the value of AA vs. DCT in the first-line treatment of metastatic prostate cancer.

Materials and Methods:

We developed Markov models by using a US-payer perspective and a 3-year time horizon to estimate costs (2018 US$) and progression-free quality-adjusted life years (PF-QALYs) for ADT alone, DCT, and AA. Health states were defined as initial state, treatment states according to experience of an adverse event, and progressed disease/death. State transition probabilities were derived from rates for drug discontinuation, frequency of adverse events, disease progression, and death from the randomized phase III trials CHAARTED and LATITUDE. Univariate and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate model uncertainty.

Results:

DCT resulted in an increase of 0.32 PF-QALYs and $16,100 in cost and AA resulted in an increase of 0.52 PF-QALYs and $215,800 in cost compared to ADT alone. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for DCT vs ADT was $50,500/PF-QALY and for AA vs DCT was $1,010,000/PF-QALY. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis demonstrated that at a willingness-to-pay threshold of $150,000/PF-QALY AA was highly unlikely to be cost-effective.

Conclusion:

DCT is substantially more cost-effective than AA in the treatment of metastatic hormone naïve prostate cancer.

Introduction

Prostate cancer accounts for nearly 30,000 deaths annually in the US, and progressive metastatic disease carries significant morbidity.1 Until 2015, the standard of care for frontline treatment of men with metastatic prostate cancer was androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) alone, either through surgical or chemical castration. Though initially effective for most patients, castration-resistance and clinical progression inevitably occurs at a median of approximately one year.2,3 In an analysis of men presenting with de novo metastatic prostate cancer between 1988 to 2009, no improvement in overall or disease-specific survival was found over time.4 From 2010 to 2014, six new agents were FDA approved for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), but ADT alone remained the preferred first line therapy for metastatic hormone-naïve prostate cancer (mHNPC).

However, since 2015, three landmark studies have established a role for two agents that were initially approved for castration-resistant disease for use in the initial metastatic hormone-naïve setting. The ECOG-ACRIN 3805 (CHAARTED) and STAMPEDE studies treated patients with 6 cycles of docetaxel (DCT) at the time of ADT initiation prior to the development of castration resistance, and demonstrated an improvement in time to progression as well as overall survival.5,6 Shortly thereafter, the LATITUDE and STAMPEDE studies demonstrated that the addition of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone (AA) therapy concomitantly with ADT improved progression-free and overall survival.7,8

While the STAMPEDE study had a more heterogeneous population as it included patients with non-metastatic disease, the CHAARTED and LATITUDE study populations were very similar, particularly when comparing the high-volume cohort from CHAARTED with the entire cohort from LATITUDE. The reported hazard ratios for overall survival compared with ADT alone (with similar median follow up times of approximately 30 months) were strikingly similar at 0.62 for AA and 0.60 for DCT. These dramatic improvements have led to the FDA approval of both drugs for mHNPC and NCCN category 1 recommendations for their use. However, these treatment approaches are vastly different in their mechanisms of action, modes of delivery, toxicity profiles, and costs.

We conducted a comparative effectiveness study of the two treatment strategies versus ADT alone based on the CHAARTED and LATITUDE trials, as there is no prospective head-to-head comparison of AA vs DCT in this setting to help guide treatment decisions. We created a Markov model to estimate treatment effects and costs to provide insight into the value of these different therapies in first-line treatment of mHNPC over the first 3 years from the time of diagnosis.

Methods

Model Structure:

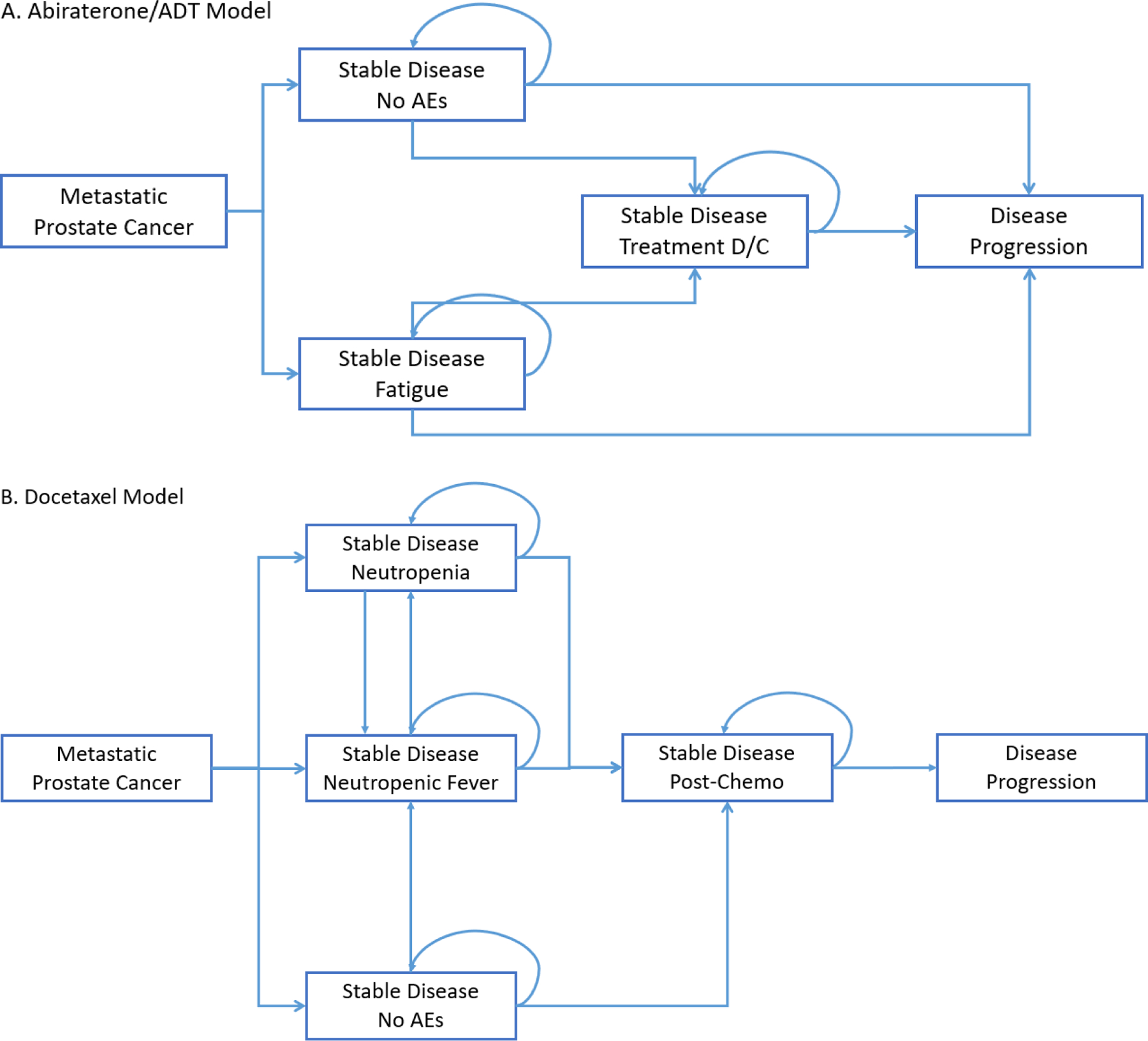

We used a Markov Cohort model to estimate costs, progression-free quality adjusted life years (PF-QALYs), and incremental cost effectiveness ratios (ICERs) for the 3 treatment strategies of AA, DCT, and ADT in patients with mHNPC from a US payer perspective. State transitions probabilities were defined according to the model structure (Figure 1), probabilities of adverse events, and survival time data. Each model cycle represented 3 weeks, corresponding to the length of a DCT treatment cycle. We limited the time horizon to 3 years, since the available follow-up for the LATITUDE trial is restricted to 3 years. AEs included in the model were chosen if they were relatively frequent and expensive to treat or substantively effected quality of life. Progression-free survival time was defined from time from initiation of treatment until progression or death. Costs and PF-QALYs accrued according to the length of time spent in various states. All analyses were completed using the package “heemod” in R software.9

Figure 1:

Markov Models for (A) Abiraterone Acetate and Androgen Deprivation Therapy Alone, and (B) Docetaxel

Model Probabilities:

The probability of transition from a stable disease state to a progressive disease state was derived from the progression-free (PFS) and overall (OS) survival curves in the CHAARTED and LATITUDE trial publications. A plot digitizer software (DigitizeIt, version 2.0, www.digitizeit.de) was used to extract data points along the survival curves of both the intervention and placebo arms of each trial. We then inferred the underlying event times and censoring statuses using the digitized survival probabilities and the number of patients at risk in a given interval.10 These data were then used to fit parametric Weibull survival models (Figure S1), which in turn defined model transition probabilities at each cycle. The PFS definitions for CHAARTED and LATITUDE differ in the inclusion of death as part of the PFS definition, with CHAARTED not categorizing death as an event. Therefore, censored progression times which occurred at the time of a death were re-categorized as a combined progression/death event.

Overall treatment discontinuation and AE rates for DCT and AA were obtained from the CHAARTED and LATITUDE trials, respectively. We used the CHAARTED breakdown of number of DCT cycles given to simulate a per cycle discontinuation rate. For the AA and ADT only models, we assumed most discontinuations occur during the first 6 months (9 cycles), and the likelihood of discontinuation was divided equally between cycles.

Utility estimates:

In order to calculate total PF-QALYs, times accrued in each state were adjusted by health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Health utility scores were derived from the quality of life data gathered in the CHAARTED and LATITUDE trials.11,12 Both trials collected data and measured quality of life outcomes using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Prostate (FACT-P) instrument. The mean FACT-P score after treatment initiation for each trial was comparable (119.0 vs 112.9), with the LATITUDE trial reporting a baseline health utility index of 0.80 as determined by the EuroQol (EQ-5D-5L).12 There was a minor, transient decrement in HRQOL associated with DCT treatment at 3 months, which then improved by 12 months. This was modeled utilizing the DCT treatment state (Figure 1). Utilities for adverse event states were obtained from the literature.11–15

Cost estimates:

Direct costs included drug acquisition, drug administration, physician visits, laboratory tests, radiographic tests, and adverse event (AE) costs. Base drug costs were the average wholesale price (AWP) minus 17% obtained from the Access Pharmacy drug monograph database, as per a previously described approach.15,16 Because oral agents are not covered by Medicare Parts A and B, this method was felt most reliable for obtaining a uniform source of drug costs. The cost of AA using this method closely approximated the costs we have observed in clinical practice, and the cost of DCT was above the average sales price from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The intravenous drug cost for each 3-week cycle of DCT was based on a dose of 75 mg/m2 administered to a patient with height 176 cm and weight 88.9 kg, median US male values, with a subsequent body surface area of 2.1 m2.17 DCT cost included dexamethasone pre-medication costs. The cost of leuprolide was for a standard, fixed 22.5mg injection given once every 3 months. Abiraterone acetate, prednisone, and peg-filgrastim doses were fixed, not weight-based. Administration costs for docetaxel, leuprolide, and peg-filgrastim were obtained from the CMS physician fee schedule. Radiographic test costs were also obtained from the CMS physician fee schedule.18 Laboratory test costs were obtained from the CMS Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule Files.19 The cost of treatment of febrile neutropenia included drugs costs, cost of hospitalization, and inpatient physician fees, as described in prior cost-effectiveness analysis, with the sum inflated to 2018 dollars using the Medical Care Services component of the Consumer Price Index.20,21

Lower bound costs for the cost sensitivity analysis were obtained from the National Acquisition Center Contract Catalog Search Tool, which shows the cost at which the Veterans Affairs and other federal government agencies are able to acquire medications.22 This represents a verifiable, practical lower bound for cost in the United States. Upper bound costs were the AWP as obtained from Access Pharmacy.16

Sensitivity Analysis:

We assessed the impact of model assumptions and tested its robustness via several sensitivity analyses. We conducted a series of one-way sensitivity analyses, varying one of the following parameters at a time: costs, survival time (via a hazard ratio), probability of neutropenia/febrile neutropenia, and HRQOL decrement while on DCT treatment. Limits for these sensitivity analyses are shown in Table 1. Next, we conducted probabilistic sensitivity analyses with 1,000 repetitions, simulating inputs of interest as follows: costs were drawn from the gamma distribution, centered at the base case with a standard deviation (SD) of 0.1 times the mean; probabilities were drawn from the binomial, based on the number of samples in the trials, and log-hazard ratios for survival times were simulated from the normal, centered at zero with SD of 0.1. We summarized results using cost-effectiveness acceptability curves to project the probability of cost-effectiveness for the treatment strategies at various willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds.

Table 1:

Model Inputs, including costs and utility values, with base case variables, range, and type of distribution used in sensitivity analyses

| Variable | Value | Minimum | Maximum | Reference | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Utility Values | |||||

| SD on AA or ADT alone | 0.83 | 0.83 | 1 (AA only) | Chi 201812 | N/A |

| SD on DCT | 0.78 | N/A | N/A | Morgans 201811 | N/A |

| Post-DCT recovery state# | 0.78–0.83 | N/A | N/A | Morgans 201811 | N/A |

| Fatigue | 0.78 | N/A | 0.95 (when AA=1) | Bayoumi 200013 | N/A |

| Febrile Neutropenia | 0.47 | N/A | N/A | Younis 201114 | N/A |

| Progression/Death | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Progressed Disease (sensitivity model to death only) | 0.725 | N/A | N/A | Zhong 201315 | N/A |

| Survival probability at 2 years* | |||||

| ADT | 33% | 26% (HR=1.2) | 41% (HR=0.85) | CHAARTED, LATITUDE5,7 | Normal (log-HR) |

| DCT | 51% | 46% (HR=1.2) | 58% (HR=0.85) | CHAARTED5 | Normal (log-HR) |

| AA | 61% | 55% (HR=1.2) | 67% (HR=0.85) | LATITUDE7 | Normal (log-HR) |

| AE rates | |||||

| DCT discontinuation | 0.12 | N/A | N/A | CHAARTED5 | N/A |

| AA discontinuation | 0.12 | N/A | N/A | LATITUDE7 | N/A |

| Fatigue (ADT) | 0.01 | N/A | N/A | LATITUDE7 | N/A |

| Fatigue (AA) | 0.02 | N/A | N/A | LATITUDE7 | N/A |

| Neutropenia (DCT) | 0.121 | 0.089 | 0.157 | CHAARTED5 | Binomial |

| Febrile Neutropenia (DCT) | 0.061 | 0.04 | 0.09 | CHAARTED5 | Binomial |

| Costs (USD) | |||||

| Drugs/Routine | |||||

| ADT (q3 month) | 1115 | 612 | 1343 | Access Pharmacy,16 VA22 | Gamma |

| ADT non-drug costs (per cycle)Δ | 137 | N/A | N/A | CMS18,19 | N/A |

| AA (per month) | 9368 | 5550 | 11275 | Access Pharmacy,16 VA22 | Gamma |

| AA non-drug costs (per cycle)Δ | 151 | N/A | N/A | CMS18,19 | N/A |

| DCT (per 3 wk cycle) | 1576 | 266 | 1710 | Access Pharmacy,16 VA22 | Gamma |

| DCT non-drug costs (per cycle)Δ | 374 (on trt)/ 142 (post-trt) |

N/A | N/A | CMS18,19 | N/A |

| AEs | |||||

| Neutropenia$ | 5937 | 3579 | 7149 | Access Pharmacy,16 VA22 | Gamma |

| Febrile neutropenia | 18507 | 5843 | 29217 | Lyman 200920 | Gamma |

Assumes linear gain between utility on treatment and after recovery, with full recovery at 12 months from treatment start

Cycle-specific probabilities calculated based on full curves and hazard ratios, 2-year survival probabilities included here to illustrate effects

Cost of peg-filgrastim plus administration

Includes medication administration, physician visits, routine labs, imaging

In separate models, we also calculated the ICER for non-quality adjusted PF-LY, and explored estimation of QALYs by including a separate “progressed disease” state (Figure S1). Finally, we re-estimated the results assuming that the price of AA was decreased by 75%, corresponding to recent data showing that a one-quarter dose (250 mg) of AA given with food is similarly efficacious to standard dose AA 1000 mg taken fasting.23 This price also represents a lower limit of the reduced prices that may be available now that generic AA has been approved by the FDA.24

Results

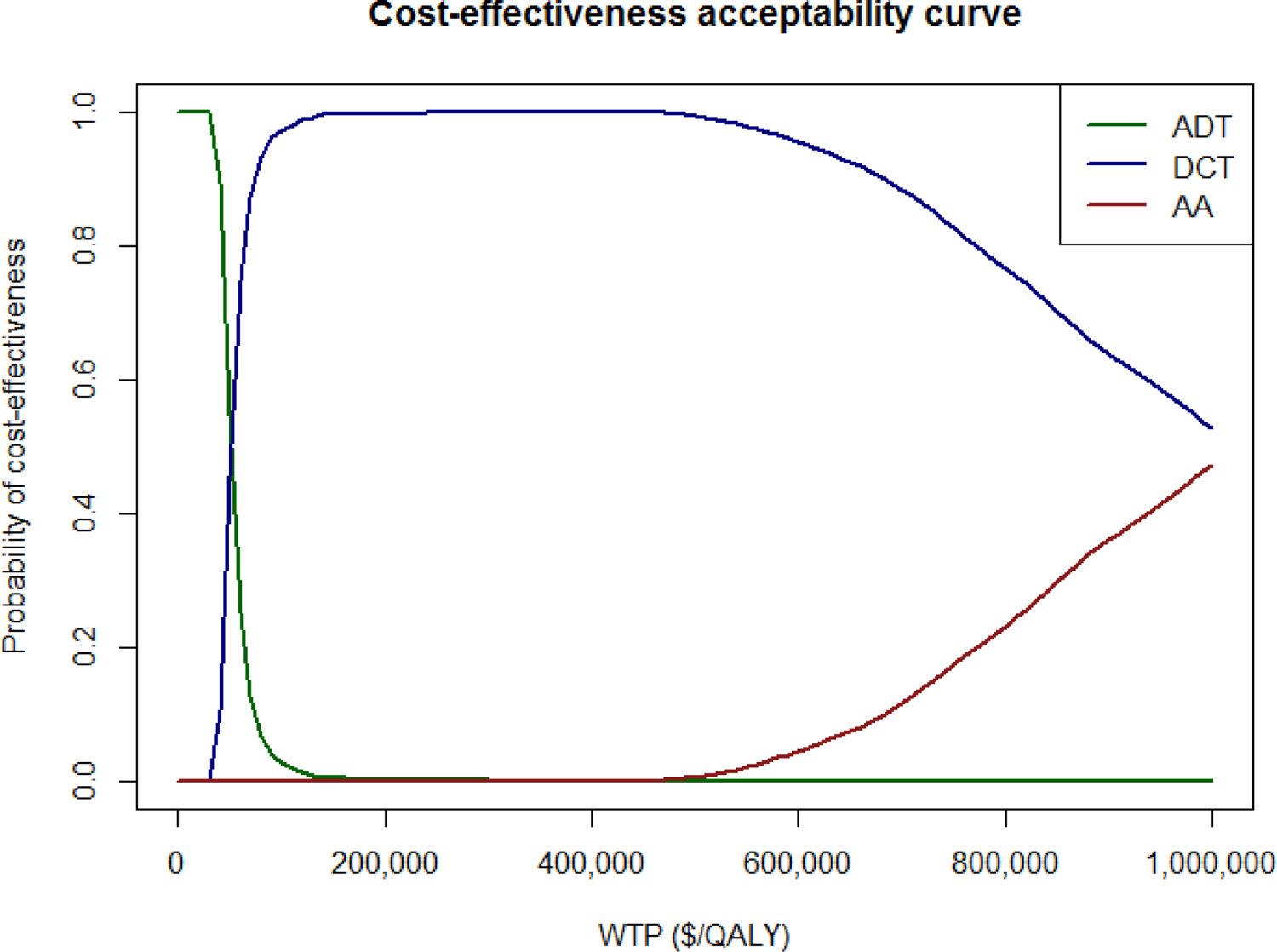

In the base case, over a 3-year time horizon, adding DCT to ADT resulted in an increase of 0.32 PF-QALYs and $16,100 in cost, and adding AA to ADT resulted in an increase of 0.52 PF-QALYs and $215,800 in cost. This results in an ICER for DCT vs ADT of $50,500/PF-QALY, and an ICER of AA vs DCT of $1,010,000/PF-QALY. One-way sensitivity analyses demonstrated that the model was most sensitive to changes in survival probabilities for each agent (Figure 2 – Tornado diagrams). Results were also sensitive to the cost of AA and DCT, and higher utilities for AA. Figure 2 demonstrates the probabilistic sensitivity analysis. Even at a willingness-pay-threshold of $150,000/PF-QALY, AA remained highly unlikely to be cost-effective. DCT remained cost-effective in 99.5% of sampled parameters at the same WTP threshold. Even at $1,000,000/PF-QALY, AA was only cost-effective in 47.7% of simulated scenarios.

Figure 2:

Tornado diagrams for univariable sensitivity analyses

Table 2B presents ICERs using the main study model under alternate scenarios. This includes the lower bound cost for AA from the VA costs, and AA at one-fourth the price which may approximate the ultimate generic cost of the medication. With the substantial price decreases, the ICERs became $575,000/PF-QALY and $208,100/PF-QALY, respectively. The model was also run without quality-of-life adjustment, and the ICER was not meaningfully different from the quality-adjusted scenario. When separating death and progression states, we assumed a fixed cost of $5,000 per month spent in progressed disease, and decreased utility (assuming some patients become symptomatic).25 This analysis confirmed that AA and DCT both offer improved outcomes over ADT, but are more costly. The differences between AA and DCT for both costs and effects were much smaller than in our base case model, but DCT retained a cost advantage over AA while QALY advantages became negligible.

Table 2B,

Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratios – Base Case and Alternate Scenarios

| ICER | ||

|---|---|---|

| DCT vs ADT | DCT vs AA | |

| Main Model (PF-QALYs) | $50,489 | $1,009,975 |

| No QALY adjustment (PF-LYs) | $44,368 | $969,532 |

| Model VA price (PF-QALYs) | $50,489 | $575,031 |

| Model with 1/4 dose (PF-QALYs) | $50,489 | $208,062 |

Discussion

We performed a cost-effectiveness analysis of AA plus ADT and DCT plus ADT in the treatment of hormone naïve metastatic prostate cancer. While both strategies provided incremental benefit compared to ADT alone, the incremental cost per PF-QALY was substantially higher for AA than DCT. This is despite the model being intentionally structured to favor AA, in that it does not ascribe additional side effects to AA compared to ADT alone and generously discounts utility values associated with a neutropenic fever state. The ICER for AA compared to DCT was sensitive to the cost of AA, but even under the lowest AA cost utilizing univariate sensitivity analysis of the VA FSS price, the ICER for AA compared to DCT remained high, at $575,100/PF-QALY. In a probabilistic sensitivity analysis, the probability of AA being cost effective was 0% at a WTP threshold of $150,000, whereas the probability of DCT being cost effective was 99.5% at the same threshold.

To our knowledge, this is the first formal cost-effectiveness analysis comparing these two strategies in first-line treatment of mHNPC. Prior studies have evaluated the cost-effectiveness of the DCT approach alone but have not extensively modeled AEs, used a US payer perspective, or compared DCT to AA.26–28

We primarily report on PF-QALYs in this study and built a detailed model to progression for calculation of ICERs rather than focusing on modeling to death. The ICER for PF-QALY is an informative measure in this setting because overall survival is similar between AA and DCT, and the relatively longer length of front-line therapy with AA compared to therapy after progression to CRPC makes cost to first progression a major driver of overall cost. While the difference in cost will be reduced when patients cross over from DCT in the hormone naïve setting to AA in the castration resistant setting, the median duration of AA in the hormone naïve setting per the LATITUDE study was 33 months, 16.5 months in the pre-docetaxel castration resistant-setting in COU-AA-302 study, and only 8 months in the post-docetaxel castration-resistant setting per COU-AA-301.7,29 Thus, we hypothesize that the cost effectiveness of DCT in the first line compared with AA will be preserved even when modeling to death and accounting for crossover. This is supported by our sensitivity analyses where PD is considered a separate state. Given the variety of treatment options and sequences available for the treatment of mCRPC, modeling beyond first progression was felt to be imprecise and fraught with too many assumptions that would detract from the strength of the cost-effectiveness conclusions.

The large difference in cost-effectiveness between DCT and AA demonstrated in this study despite the remarkably similar overall survival data for these treatment strategies raises several issues. AA would require a substantial reduction to be a cost-effective intervention at a WTP threshold of $150,000. This highlights the ongoing debate over appropriate drug pricing. When drugs are approved for an initial indication and priced according to that indication, their approval in another setting can have significant economic impact. This interestingly was an issue with abiraterone in the UK when it was first appraised favorably by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellent for an indication post-docetaxel for mCRPC, then underwent contentious review for approval in the pre-docetaxel setting.30 The importance of treatment sequence to cost has also been demonstrated in advanced melanoma, where the ICER for nivolumab plus ipilimumab combination therapy in the front line compared to pembrolizumab followed by ipilumumab on progression was over $1.7 million.31

It also highlights the importance of biomarker discovery from STAMPEDE, CHAARTED, and LATITUDE to help identify whether there are particular populations expected to benefit from one treatment or another. In the absence of these, the decision to use docetaxel or abiraterone revolves around potential side-effect differences, patient and clinician preferences, indirect or retrospective comparisons, and occasionally clinical factors such as visceral or very large volume disease status.

As with any modeling study, our analysis has certain limitations. The models we developed were based on data from previously published trials and not prospectively collected. While this may affect real-world applicability, it did enable us to use standardized costs and high-quality survival and adverse event data. The overall survival data from LATITUDE were not mature, with only 3 years of follow-up for the study; therefore, we focused on PF-QALYs over a 3-year window. This allowed for a comparison between DCT and AA without reliance on extrapolated survival curves, or hypothetical models for treatments in the castration-resistant setting. Given the PFS benefit for AA, it is possible that future studies with longer follow-up may indicate some OS benefit over DCT; however, given the lack of any demonstrable difference at 3 years, large differences in OS are unlikely. Indeed, longer term follow-up from CHAARTED showed that in high-volume patients, the hazard ratio for OS remained 0.62.32

We used established health utility values from the literature based on recently published quality of life data from the LATITUDE and CHAARTED studies.11,12 Although the utility for DCT was lower than for AA, given clinical experience we were surprised to see a relatively minor difference between the two treatments (a difference of 0.05). We therefore ran additional sensitivity analyses where the utility of SD on AA was increased to the extreme value of 1. Although this did result in a more favorable ICER for AA, it was still high at $361,800/PF-QALY.

There is no universal standard for drug cost ascertainment in cost-effectiveness analysis, but we used the average wholesale price minus 17% for drugs in our base case scenario and the US Federal Supply Service price for the lower bound in our sensitivity analysis, making our analysis applicable primarily to the US setting.15 We assumed fixed drug acquisition costs; thus, the generic docetaxel was advantaged compared to the patented abiraterone acetate cost. The recent launch of generic abiraterone in the US will mitigate some of the effect difference as we demonstrated but, as has been documented in the case of imatinib, the loss of patent and entry of generic equivalents can be slow and modest in effecting price reductions.33

Our data should contribute to the ongoing debate on the optimal first line therapy for mHNPC. Societal cost is not the sole factor in this treatment decision – there are differences in side effect profiles, treatment lengths, costs to the individual patient, and availability between these treatments. Further studies are needed to identify predictive biomarkers for differential benefit to these treatment strategies. However, the vast difference in cost-effectiveness between DCT and AA in mHNPC despite comparable survival results should inform how we as a society allocate our healthcare resources.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3:

Cost Effectiveness Acceptability Curve for Three Treatment Strategies

Table 2A,

Base Case Results

| Main Model | Costs | PF-QALYs | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADT | $10,350 | 1.21 | |

| DCT | $26,450 | 1.53 | $50,489 |

| AA | $226,183 | 1.73 | $1,009,975 |

References

- 1.Weiner AB, Matulewicz RS, Eggener SE, et al. : Increasing incidence of metastatic prostate cancer in the United States (2004–2013). Prost Canc Prost Dis 19:395–397, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gravis G, Fizazi K, Joly F, et al. : Androgen-deprivation therapy alone or with docetaxel in non-castrate metastatic prostate cancer (GETUG-AFU 15): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 14:149–58, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James ND, Spears MR, Clarke NW, et al. : Survival with Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Prostate Cancer in the “Docetaxel Era”: Data from 917 Patients in the Control Arm of the STAMPEDE Trial (MRC PR08, CRUK/06/019). Eur Urol 67:1028–1038, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu JN, Fish KM, Evans CP, et al. : No improvement noted in overall or cause-specific survival for men presenting with metastatic prostate cancer over a 20-year period. Cancer 120:818–823, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sweeney CJ, Chen Y-H, Carducci M, et al. : Chemohormonal Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. NEJM 373:737–746, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James ND, Sydes MR, Clarke NW, et al. : Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet 387:1163–1177, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, et al. : Abiraterone plus Prednisone in Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. NEJM 377:352–360, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, et al. : Abiraterone for Prostate Cancer Not Previously Treated with Hormone Therapy. NEJM 377:338–351, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filipovic-Pierucci A, Zarca K, Durand-Zaleski I: Markov Models For Health Economic Evaluation Modelling In R With The Heemod Package. Value in Health 19:A369, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guyot P, Ades AE, Ouwens MJNM, et al. : Enhanced secondary analysis of survival data: reconstructing the data from published Kaplan-Meier survival curves. BMC Medical Research Methodology 12:9, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgans AK, Chen Y-H, Sweeney CJ, et al. : Quality of life during treatment with chemohormonal therapy: analysis of E3805 chemohormonal androgen ablation randomized trial in prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 36:1088, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chi KN, Protheroe A, Rodríguez-Antolín A, et al. : Patient-reported outcomes following abiraterone acetate plus prednisone added to androgen deprivation therapy in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic castration-naive prostate cancer (LATITUDE): an international, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 19:194–206, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bayoumi AM, Brown AD, Garber AM: Cost-Effectiveness of Androgen Suppression Therapies in Advanced Prostate Cancer. JNCI 92:1731–1739, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Younis T, Rayson D, Skedgel C: The cost–utility of adjuvant chemotherapy using docetaxel and cyclophosphamide compared with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide in breast cancer. Curr Oncol 18:e288, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong L, Pon V, Srinivas S, et al. : Therapeutic Options in Docetaxel-Refractory Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. PLOS ONE 8:e64275, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.AccessPharmacy: Drug Monographs, https://accesspharmacy.mhmedical.com/drugs.aspx

- 17.CDC/National Center for Health Statistics: Body Measurements, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/body-measurements.htm

- 18.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Medicare physician fee schedule, http://www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/

- 19.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule Files, https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/Clinical-Laboratory-Fee-Schedule-Files.html#

- 20.Lyman GH, Lalla A, Barron RL, et al. : Cost-effectiveness of pegfilgrastim versus filgrastim primary prophylaxis in women with early-stage breast cancer receiving chemotherapy in the united states. Clin Therap 31:1092–1104, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Dept of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics: CPI Inflation Calculator, https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl

- 22.U.S. Dept of Veterans Affairs: National Acquisition Center Contract Catalog Search Tool, https://www.va.gov/nac/

- 23.Szmulewitz RZ, Peer CJ, Ibraheem A, et al. : Prospective International Randomized Phase II Study of Low-Dose Abiraterone With Food Versus Standard Dose Abiraterone In Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J Clin Oncol 36:1389–1395, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Food & Drug Administration: Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm

- 25.Chastek B, Harley C, Kallich J, et al. : Health care costs for patients with cancer at the end of life. J Oncol Pract 8:75s–80s, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng H, Wen F, Wu Y, et al. : Cost-effectiveness analysis of additional docetaxel for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer treated with androgen-deprivation therapy from a Chinese perspective. Eur J Canc Care 26:e12505, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang P, Wen F, Fu P, et al. : Addition of docetaxel and/or zoledronic acid to standard of care for hormone-naive prostate cancer: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Tumori 103:380–386, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aguiar PN Jr, Barreto CMN, Gutierres BdS, et al. : Cost effectiveness of chemohormonal therapy in patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive and non-metastatic high-risk prostate cancer. Einstein (São Paulo) 15:349–354, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, et al. : Abiraterone in Metastatic Prostate Cancer without Previous Chemotherapy. NEJM 368:138–148, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramaekers BL, Riemsma R, Tomini F, et al. : Abiraterone acetate for the treatment of chemotherapy-naïve metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: an evidence review group perspective of an NICE single technology appraisal. Pharmacoeconomics 35:191–202, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kohn CG, Zeichner SB, Chen Q, et al. : Cost-Effectiveness of Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in BRAF Wild-Type Advanced Melanoma. J Clin Oncol 35:1194–1202, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kyriakopoulos CE, Chen Y-H, Carducci MA, et al. : Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: long-term survival analysis of the randomized phase III E3805 CHAARTED trial. J Clin Oncol 36:1080, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen CT, Kesselheim AS: Journey of Generic Imatinib: A Case Study in Oncology Drug Pricing. J Oncol Pract 13:352–355, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.