Abstract

Inflammation caused by neuropathy contributes to the development of neuropathic pain (NP), but the exact mechanism still needs to be understood. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), an important inflammation regulator, might participate in the inflammation in NP. To explore the role of PPARα in NP, the effects of PPARα agonist WY-14643 on chronic constriction injury (CCI) rats were evaluated. The results showed that WY-14643 stimulation could decrease inflammation and relieve neuropathic pain, which was relative with the activation of PPARα. In addition, we also found that the SIRT1/NF-κB pathway was involved in the WY-14643-induced anti-inflammation in NP, and activation of PPARα increased SIRT1 expression, thus reducing the proinflammatory function of NF-κB. These data suggested that WY-14643 might serve as an inflammation mediator, which may be a potential therapy option for NP.

1. Introduction

Neuropathic pain (NP), a complicated disease of the somatosensory nervous system, affects 7%-10% of the general population worldwide [1]. Patients who are diagnosed with NP will be accompanied with shooting and burning pain and tingling sensation so that their life quality decreases [2]. At present, the causative factors of NP is underestimated and the management of NP is on challenge [1]. Many studies show that there exists immune system dysfunction in NP, which leads to the process of allergic inflammation, as a way of the elevated proinflammatory cytokines and decreased anti-inflammatory cytokines [3–7]. However, the molecular mechanism of inflammation in NP still needs to be well established.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) that belongs to PPAR families is a ligand-activated transcription factor that regulates lipid metabolism, neuronal survival, cardiac pathophysiology, cell cycle, and inflammation [8, 9]. It is reported that PPARα exhibits inflammation-suppressing effects in obesity, atherosclerosis, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, and acute kidney injury [10–13], but the role of PPARα in inflammation in NP still remains unclear. WY-14643, as a PPARα agonist, has been proved to reduce inflammation in several pathological processes [14]. Nevertheless, whether WY-14643 can suppress inflammation in NP is not elaborated.

Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), a nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide-dependent class III histone/protein deacetylase, participates in many cellular processes including aging, cell cycle, differentiation, apoptosis, metabolism, and inflammation [15, 16]. It is widely accepted that SIRT1 functioned as an inhibitor of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling and p65 acetylation was considered a pacemaker of the NF-κB pathway [17]. Subsequent accumulating evidence shows that SIRT1 has the capacity of inhibiting inflammation by NF-κB inhibition [18, 19].

In this study, we hypothesized that WY-14643 could alleviate the inflammation in NP via SIRT1/NF-κB signaling. To verify the hypothesis, the chronic constriction injury (CCI) rat model was established. Pain tests were performed to examine whether WY-14643 could relieve the NP in CCI rats, and the expression of proinflammatory cytokines was detected to evaluate the inflammation in CCI rats.

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (200-250 g, 8 weeks) were used in this study and purchased from Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital. All rats were randomly divided into 10 groups (n = 6). The animal experiments were approved by People's Hospital of Hangzhou Medical College and performed in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (2011).

2.2. CCI Model

Chronic constriction injury (CCI) surgery was performed according to the procedure described by Bennett and Xie [20]. Rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (40 mg/kg, i.p.). An incision was made below the hip bone and parallel to the sciatic nerve. In the CCI rat groups, the bilateral sciatic nerves of two legs were exposed and ligated loosely by 4-0 chromic gut sutures with about 1 mm spacing, while nothing was ligated in the sham group. The surgery was performed by the same researcher. After operation, CCI rats gradually showed typical signs of spontaneous hyperalgesia, but the behavioral performance of the sham group is the same as before the operation.

After surgery, the CCI rats were treated with WY-14643 (10 mg/kg) [21]; GW6471 (30 mg/kg) [22]; and si-SIRT1 (250 nm/kg); the drugs were given by intrathecal injection. Two hours after the injection, pain tests were performed.

2.3. Pain Tests

2.3.1. Mechanical Hyperalgesia

Paw withdrawal mechanical threshold (PWMT) [23] was determined applying electronic von Frey filament. Put the rats into plexiglass boxes (50 × 30 × 30 cm) with metal mesh floor. The filament was pressed on the plantar surface until the rats withdraw their paws. Record the values displayed by the electronic von Frey filament. Repeat each measurement 3 times at a 5-minute interval.

2.3.2. Thermal Hyperalgesia

Paw withdrawal thermal latency (PWTL) [23] was determined using the thermal radiation. Put the rats into plexiglass boxes for more than 30 minutes to adapt to the environment. The heat source was pointed at the plantar surface of the hind paws, and the time when rats show paw withdrawal was recorded. The thermal stimulus was repeated 3 times at 5-minute interval, and the average value was considered PWTL. All behavioral tests were performed by the same person.

2.4. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

When all pain tests were finished, the rats were decapitated immediately. Collect the serum and store it in a -80°C refrigerator. The L4-6 spinal cord was frozen by liquid nitrogen. Total RNA of the frozen spinal cord was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA), and the concentration of RNA was measured using NanoDrop 2000. Then, the reverse transcription PCR was performed using PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara, Japan). The qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara, Japan) and run on the ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies, USA). GAPDH was used as internal control. The relative expression was calculated with the 2-ΔΔCT algorithm.

2.5. ELISA

The TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels of serum and spinal cords were detected using Rat TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 Precoated Kits (Dakewe, China).

2.6. Western Blot

The frozen samples were lysed using T-PER Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermo Scientific, USA). Protein concentration was measured by BCA Protein Assay Kit (Leagene, China). 30 μg protein was separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (anti-SIRT1, 1 : 1000; anti-acetyl-NF-κB p65, 1 : 1000) overnight at 4°C and secondary antibodies (1 : 5000) at room temperature for 1 h. Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad, USA) was used to visualize the protein bands. ImageJ was used to analyze the gray value of protein bands.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Results were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. The significance of the difference between two groups is determined by Student's t-test; differences between more than three groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance. The SPSS 23.0 (IBM, USA) and GraphPad Prism 6. Ink (GraphPad, California) were used for major analysis. P < 0.05 was regarded statistically significant.

3. Results

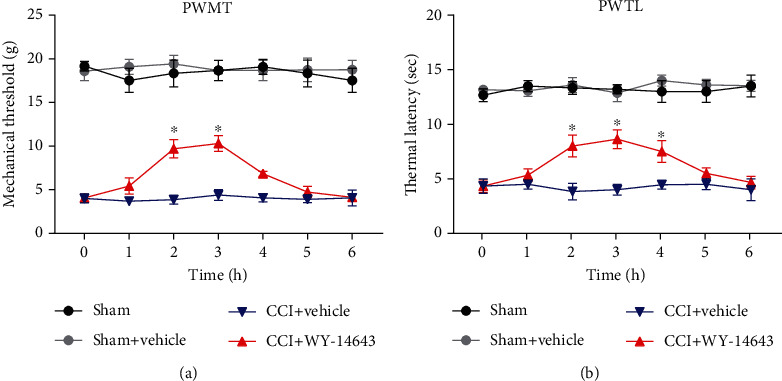

3.1. Acute WY-14643 Treatment Temporarily Alleviates NP

WY-14643 is a synthetic PPARα agonist; current researches show that PPARα plays a role in the development of NP. Therefore, to determine the antinociceptive effect of WY-14643 in NP, CCI rats were treated with WY-14643. Mechanical hyperalgesia and thermal allodynia were evaluated by PWMT and PWTL. Compared with the sham group, the PWMT and PWTL of the CCI group were significantly reduced. However, the PWMT was increased between 2 and 3 h after WY-14643 administration (Figure 1(a)). The PMTL was also improved between 2 and 4 h by WY-14643 treatment (Figure 1(b)). These results indicated that acute WY-14643 administration relieved NP temporarily.

Figure 1.

Acute WY-14643 treatment temporarily alleviated NP. (a) WY-14643 improved the paw withdrawal mechanical threshold (PWMT) of CCI rats. (b) WY-14643 improved the paw withdrawal thermal latency (PWTL) of CCI rats.

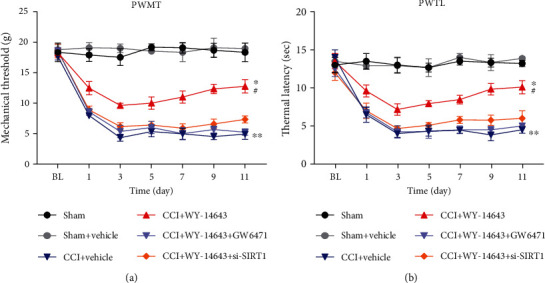

3.2. Repeated WY-14643 Administration Alleviates NP in CCI Rats by Activating PPARα

Given the above findings, we next tested whether repeated WY-14643 treatment could promote the recovery of NP in CCI rats. Rats were treated with WY-14643 once a day for 11 days after surgery. In addition, it has been reported that SIRT1 is involved in inflammation regulation and interacts with PPAR. Therefore, PPARα antagonist GW6471 (MedChemExpress, USA) and in vivo si-SIRT1 (RiboBio, China) were also used to explore the mechanism of WY-14643 treating NP. Mechanical hyperalgesia was significantly reduced in the WY-14643 group, but GW6471 and si-SIRT1 aggravated the pain again (Figure 2(a)). Thermal hyperalgesia was also reduced by WY-14643 administration; however, GW6471 and si-SIRT1 reversed the antinociceptive effect of WY-14643 (Figure 2(b)). These data illustrated that WY-14643 relieved NP by acting as a PPARα agonist, and SIRT1 inhibition blocked the function of WY-14643 in NP.

Figure 2.

Repeated WY-14643 administration alleviated NP in CCI rats by activating PPARα. (a) WY-14643 increased the PWMT of CCI rats, but GW6471 and si-SIRT1 reversed this effect. (b) WY-14643 increased the PWTL of CCI rats, but GW6471 and si-SIRT1 reversed this effect.

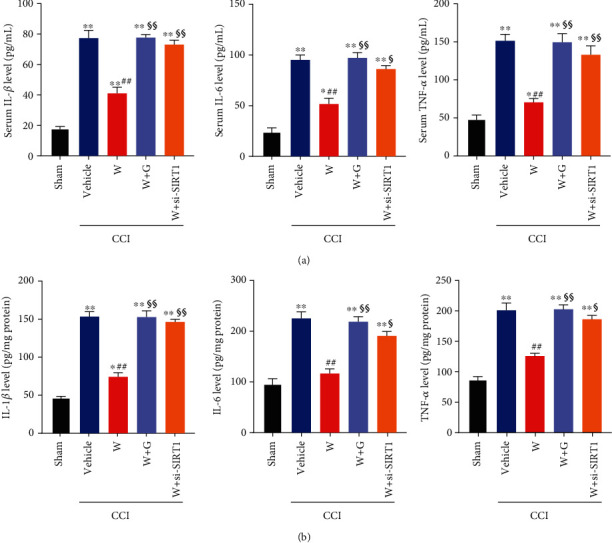

3.3. Repeated WY-14643 Administration Reduces Inflammation in CCI Rats by Activating PPARα

Recent studies indicate that activation of PPARα increases the expression and activity of SIRT1, which leads to deacetylation of p65 NF-κB, thus inhibiting the expression of inflammatory cytokines [24, 25]. Since inflammation has been reported to be involved in the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain, the expression of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α was determined using ELISA. The serum and spinal cord samples were collected immediately after finishing all behavior tests. In CCI rats, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in serum were significantly increased (Figure 3(a)). Repeated WY-14643 treatment decreases the levels of these proinflammatory cytokines. However, PPARα antagonist (GW6471) and si-SIRT1 increase IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in serum (Figure 3(a)). We also detected the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the spinal cord. WY-14643 markedly suppressed the inflammation in CCI rats, whereas GW6471 and si-SIRT1 reversed the anti-inflammatory effect induced by WY-14643 (Figure 3(b)). Taken together, the results showed that WY-14643 reduced the inflammation in NP through the PPARα/SIRT1 pathway.

Figure 3.

Repeated WY-14643 administration reduced inflammation in CCI rats by activating PPARα. (a) WY-14643 reduced IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in serum of CCI rats, whereas GW6471 and si-SIRT1 reversed the anti-inflammatory effect. (b) WY-14643 reduced IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in the spinal cord of CCI rats, whereas GW6471 and si-SIRT1 reversed the anti-inflammatory effect.

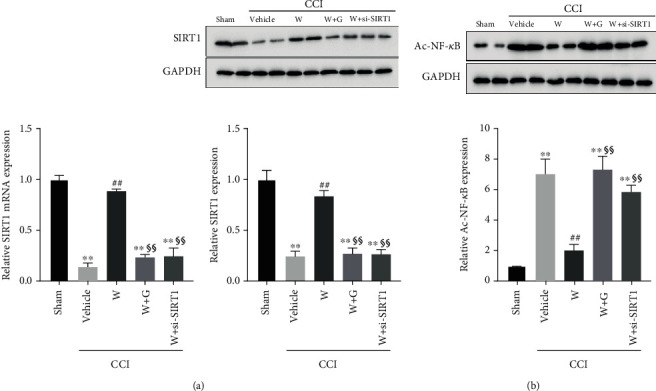

3.4. SIRT1/NF-κB Pathway Mediates WY-14643-Induced Inhibition of NP

NF-κB is a key inflammatory mediator, which participates in the regulation of inflammatory response. SIRT1, a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent deacetylase, has been shown to inhibit NF-κB signaling by deacetylating the p65 subunit of NF-κB complex [24]. To further explore the molecular mechanism of NP, we detected the expression of SIRT1 and acetylated NF-κB p65 (Ac-NF-κB p65). CCI decreases SIRT1 expression (Figure 4(a)), whereas Ac-NF-κB p65 expression was significantly increased (Figure 4(b)). WY-14643 treatment increased SIRT1 expression, thus deacetylating NF-κB p65. But GW6471 and si-SIRT1 inhibited the expression of SIRT1 and restored the Ac-NF-κB p65 expression (Figures 4(a) and 4(b)). These results demonstrated that WY-14643 alleviated NP through the PPARα-mediated SIRT1/NF-κB pathway in CCI rats.

Figure 4.

WY-14643 mediated the SIRT1/NF-κB pathway by activating PPARα. (a) The expression of SIRT1 in different groups was detected by qRT-PCR and western blot. WY-14643 administration increased SIRT1 expression. (b) The expression of acetylated NF-κB p65 in different groups was detected by western blot. WY-14643 administration decreased acetylated NF-κB p65 expression, but SIRT1 inhibition increased acetylated NF-κB p65 expression. The relative protein expression was normalized according to the gray value of the band, which was analyzed by ImageJ.

4. Discussion

The underlying basis of NP is the chronic ectopic electrical activity of nociceptive neurons. The cells located in the injury site release proinflammatory cytokines, leading to a proinflammatory environment [7]. Therefore, a deep understanding of how to reduce inflammation is urgent for NP treatment. PPARα has gained great attention for its anti-inflammatory effects in many disease models. However, the molecular mechanism between PPARα activation and inflammation in CCI model has not been fully elucidated. In this study, we first used PPARα agonist WY-14643 to explore the signaling pathway between the PPARα activation and inflammation in NP.

Firstly, we found that the PWMT and PWTL of CCI rats were significantly lower than those of the sham group, whereas PPARα agonist WY-14643 treatment would increase the PWMT and PWTL. Subsequently, we compared the effects of WY-14643 and PPARα antagonist GW6471 on the CCI rats. The significant reduction of mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in WY-14643-treated group was observed; however, GW6471 administration blocked these effects. The above results suggested that WY-14643 owned potential treatment value for NP. And this is the first time that the function of WY-14643 in NP was studied.

Previous evidences demonstrated that PPARα could activate SIRT1 and play a role in many biological processes. Oka et al. reported that the PPARα/SIRT1 pathway took part in the progression of heart failure by promoting mitochondrial dysfunction [26]. Ogawa et al. found that the repression of microglial activation was associated with SIRT1-dependent PPARα signaling [27]. Sandoval-Rodriguez et al. showed that PPARα improved nonalcoholic steatohepatitis via acting on SIRT1 [28]. However, whether the PPARα/SIRT1 pathway was involved in NP development was unclear. In CCI rats, we found that mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia was downregulated in the WY-14643 group, whereas coadministration of si-SIRT1 and WY-14643 would recover the damage again in rats. These findings proved that the PPARα/SIRT1 pathway might participate in the pathogenesis of NP.

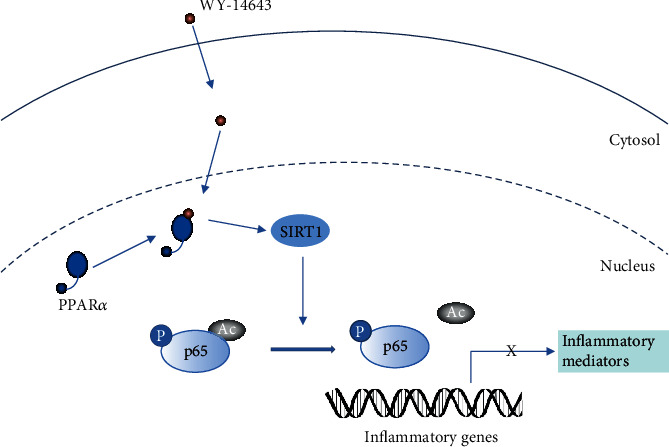

To explore the effects of PPARα/SIRT1 signaling on inflammation, we detected the expression of inflammatory cytokines and noticed that the inflammatory cytokines were evidently increased in CCI rats, but WY-14643 treatment restrained the inflammation. Further treatment with si-SIRT1 would reverse the anti-inflammatory effect stimulated by WY-14643. It suggested that PPARα/SIRT1 signaling might be relative to the inflammation progression of NP. The results were consistent with the clues that PPARα had a hand in inflammation by regulating SIRT1 [28]. Moreover, since SIRT1 was capable of bating inflammation by inhibition of NF-κB [15, 17], we also determined the levels of SIRT1 and acetylated NF-κB p65 in CCI rats. WY-14643 could make SIRT1 activated and deacetylate NF-κB p65, but GW6471 and si-SIRT1 would reduce the expression of SIRT1 and upregulate the expression of Ac-NF-κB p65. The regulating pathway is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The PPARα/SIRT1/NF-κB pathway in the inflammation in NP.

However, there are still limitations in our study. Currently, sufficient evidence to support the clinical application of WY-14643 for NP is lacking, and the side effects of WY-14643 are uncertain. Consequently, the safety of WY-14643 should be further considered. And we will also further explore the safety of WY-14643 in the future.

In conclusion, our study illustrates that PPARα agonist WY-14643 relieves inflammation in NP via the SIRT1/NF-κB pathway.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital, Wuhan Children's Hospital, and Huai'an Second People's Hospital for the support.

Contributor Information

Biyu Zhang, Email: zhangbiyu001@sina.com.

Jun Wang, Email: wangjuncn@aliyun.com.

Data Availability

All data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Wanshun Wen and Jinlin Wang performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Biyu Zhang and Jun Wang designed the experiments and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Wanshun Wen and Jinlin Wang are co-first authors.

References

- 1.Szok D., Tajti J., Nyári A., Vécsei L., Trojano L. Therapeutic approaches for peripheral and central neuropathic pain. Behavioural Neurology. 2019;2019:13. doi: 10.1155/2019/8685954.8685954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu K., Wang L. Optogenetics: therapeutic spark in neuropathic pain. Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences. 2019;19(4):321–327. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2019.4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allison D. J., Thomas A., Beaudry K., Ditor D. S. Targeting inflammation as a treatment modality for neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2016;13(1) doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0625-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander G. M., van Rijn M. A., van Hilten J. J., Perreault M. J., Schwartzman R. J. Changes in cerebrospinal fluid levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in CRPS. Pain. 2005;116(3):213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eijkelkamp N., Steen-Louws C., Hartgring S. A., et al. IL4-10 fusion protein is a novel drug to treat persistent inflammatory pain. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2016;36(28):7353–7363. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0092-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou L. J., Peng J., Xu Y. N., et al. Microglia are indispensable for synaptic plasticity in the spinal dorsal horn and chronic pain. Cell Reports. 2019;27(13):3844–3859.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuffler D. P. Mechanisms for reducing neuropathic pain. Molecular Neurobiology. 2020;57(1):67–87. doi: 10.1007/s12035-019-01757-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearsall E. A., Cheng R., Zhou K., et al. PPARα is essential for retinal lipid metabolism and neuronal survival. BMC Biology. 2017;15(1, article 113) doi: 10.1186/s12915-017-0451-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bougarne N., Weyers B., Desmet S. J., et al. Molecular actions of PPARα in lipid metabolism and inflammation. Endocrine Reviews. 2018;39(5):760–802. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stec D. E., Gordon D. M., Hipp J. A., et al. Loss of hepatic PPARα promotes inflammation and serum hyperlipidemia in diet-induced obesity. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2019;317(5):R733–R745. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00153.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hennuyer N., Duplan I., Paquet C., et al. The novel selective PPARα modulator (SPPARMα) pemafibrate improves dyslipidemia, enhances reverse cholesterol transport and decreases inflammation and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2016;249:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakhia R., Yheskel M., Flaten A., Quittner-Strom E. B., Holland W. L., Patel V. PPARα agonist fenofibrate enhances fatty acid β-oxidation and attenuates polycystic kidney and liver disease in mice. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2018;314(1):F122–F131. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00352.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwaki T., Bennion B. G., Stenson E. K., et al. PPARα contributes to protection against metabolic and inflammatory derangements associated with acute kidney injury in experimental sepsis. Physiological Reports. 2019;7(10, article e14078) doi: 10.14814/phy2.14078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang R., Wang P., Chen Z., et al. WY-14643, a selective agonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α, ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behaviors by preventing neuroinflammation and oxido-nitrosative stress in mice. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2017;153:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang S. R., Wright J., Bauter M., Seweryniak K., Kode A., Rahman I. Sirtuin regulates cigarette smoke-induced proinflammatory mediator release via RelA/p65 NF-κB in macrophages in vitro and in rat lungs in vivo: implications for chronic inflammation and aging. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2007;292(2):L567–L576. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00308.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stein S., Matter C. M. Protective roles of SIRT1 in atherosclerosis. Cell Cycle. 2014;10(4):640–647. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.4.14863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon H. S., Brent M. M., Getachew R., et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein inhibits the SIRT1 deacetylase and induces T cell hyperactivation. Cell Host & Microbe. 2008;3(3):158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J., Zhou Y., Mueller-Steiner S., et al. SIRT1 protects against microglia-dependent Amyloid-β toxicity through inhibiting NF-κB signaling. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(48):40364–40374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang W., Bai L., Qiao H., et al. The protective effect of fenofibrate against TNF-α-induced CD40 expression through SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of NF-κB in endothelial cells. Inflammation. 2014;37(1):177–185. doi: 10.1007/s10753-013-9728-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett G. J., Xie Y. K. A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain. 1988;33(1):87–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santilli A. A., Scotese A. C., Tomarelli R. M. A potent antihypercholesterolemic agent: (4-chloro-6-(2,3-xylidino)-2-pyrimidinylthio) acetic acid (Wy-14643) Experientia. 1974;30(10):1110–1111. doi: 10.1007/BF01923636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu H. E., Stanley T. B., Montana V. G., et al. Structural basis for antagonist-mediated recruitment of nuclear co-repressors by PPARα. Nature. 2002;415(6873):813–817. doi: 10.1038/415813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J., Chen H. S. Pivotal role of capsaicin-sensitive primary afferents in development of both heat and mechanical hyperalgesia induced by intraplantar bee venom injection. Pain. 2001;91(3):367–376. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00458-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kauppinen A., Suuronen T., Ojala J., Kaarniranta K., Salminen A. Antagonistic crosstalk between NF-κB and SIRT1 in the regulation of inflammation and metabolic disorders. Cellular Signalling. 2013;25(10):1939–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan S. A., Sathyanarayan A., Mashek M. T., Ong K. T., Wollaston-Hayden E. E., Mashek D. G. ATGL-catalyzed lipolysis regulates SIRT1 to control PGC-1α/PPAR-α signaling. Diabetes. 2015;64(2):418–426. doi: 10.2337/db14-0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oka S., Alcendor R., Zhai P., et al. PPARα-Sirt1 complex mediates cardiac hypertrophy and failure through suppression of the ERR transcriptional pathway. Cell Metabolism. 2011;14(5):598–611. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogawa K., Yagi T., Guo T., et al. Pemafibrate, a selective PPARα modulator, and fenofibrate suppress microglial activation through distinct PPARα and SIRT1-dependent pathways. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2020;524(2):385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.01.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandoval-Rodriguez A., Monroy-Ramirez H. C., Meza-Rios A., et al. Pirfenidone is an agonistic ligand for PPARα and improves NASH by activation of SIRT1/LKB1/pAMPK. Hepatology Communications. 2020;4(3):434–449. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available upon request.