Abstract

Objective:

Hospice family caregivers are seeking additional information related to patient care, pain and symptom management, and self-care. This study interviewed hospice staff about the potential dissemination of bilingual telenovelas to address these caregiver needs.

Methods:

Qualitative structured phone interviews were conducted with 22 hospice professionals from 17 different hospice organizations in 3 different Midwest states. The interviews were conducted from October to December 2019. Hospice staff volunteers were recruited from conferences, then individual interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and thematic analysis was conducted to gain an in-depth understanding of how to best implement telenovela video education into hospice care.

Results:

Most participants were hospice nurses (36%) located primarily in Missouri (91%), with a mean of 9 years of experience. Three discrete themes emerged, the educational resources currently provided to patient/families, perceptions of the usefulness of telenovelas for education, and practical suggestions regarding the dissemination of telenovelas. The development of 4 telenovela videos covering different topics is described.

Conclusion:

Hospice staff responded favorably to the concept of telenovelas and identified important keys for dissemination.

Keywords: hospice staff, interviews, hospice family caregivers, telenovela, videos, education, hospice care

Introduction

Eighteen million caregivers in the United States volunteer their time and energy to care for family members, saving the government an estimated US$234 billion each year.1 About 60% of the patients enrolled in hospice received care at home, a setting in which family caregivers are required to provide patients with care and symptom management, supported by regular home visits of a hospice care team.2 Nearly one-third of family care-givers of patients receiving hospice care report they are moderately to severely anxious and/or depressed.3 Research has shown that hospice caregivers are seeking additional information related to patient care, pain and symptom management, and self-care.3 Caregivers need education and assistance to make patient-centered and family-centered care a reality for hospice patients.4

Current caregiver support offered by hospice agency is commonly limited to respite care, one-on-one education, and/or referral to a support group. However, these types of generic interventions do not meet every caregiver’s needs, which vary across illness trajectory and burden varies based on subjective experiences and social support.5 While caregivers rate communication of information6 as essential to the support they receive and seek in regular contact with hospice providers, it is in many cases not practical for them to obtain all the information necessary during the hospice visit nor to attend support group meetings. Mostly due to inability to absorb or understand verbal information, lack of time, geographic constraints, and concerns leaving a frail loved one alone. Furthermore, hospice agencies may not be able to easily increase the number of visits to the patient’s home, making the development of technological hospice resources a vital step to improve communication of hospice providers with patients and caregivers.

Video is an increasingly utilized media for patient and family education. Video has been shown to improve decision-making by providing visual information to capture complex medical and emotional scenarios.7 Video support tools created to educate about comfort care when facing a terminal cancer diagnosis has been demonstrated to increase patient knowledge8 and the likelihood that patients opt for comfort care at end of life.9,10 Telenovela, a form of television drama used broadly in Latin American countries, is one format of video education with storytelling that can be used for learning about health, leading viewers to discuss the story and initiate changes.11 Prior work with telenovelas, teaching through a brief dramatic story, had a positive effect on Latino family caregivers of older adults’ attitudes toward end-of-life (EOL) care services.12 The role of videos in hospice and palliative care shows significant promise13,14 underscoring their use as a mode of education for family caregivers that could potentially enhance caregiver’s outcomes related to stress of caregiving at EOL. The aim of this article is to describe the development of telenovela and explore hospice staff views of telenovela implementation strategies.

Background

The ACCESS (Access for Cancer Caregivers to Education and Support for Shared decision-making) clinical trial was testing the impact of social and educational support through online support groups. Based on identified hospice caregiver educational needs, 6 traditional educational videos using recorded power-point were created. They included information about hospice, social support, self-care, final hours, pain assessment, and shared decision-making. They were disseminated through an online support group. As a result of low engagement,15 we explored moving to a new format, namely, telenovela, different from standard-teaching video-recorded presentation originally used in ACCESS.

Telenovela as Educational Tool

Storytelling has been found to be a beneficial learning method, especially in rural areas.16 A 2013 study found that the telenovela format was an innovative way to communicate colorectal cancer health messages with Alaska Native, American Indian, and Caucasian people, both in an urban and in a rural setting, to facilitate conversations and action related to colorectal cancer screening.17 A telenovela is usually a television show that narrates stories of a few people intertwined into a dramatic plot; unlike soap operas, telenovelas are designed with an ending. Out of 4 studies identified as using telenovelas for family caregivers (Webnovela Mirela, Fixing Paco, Todo ha cambiado and Ladron de Corazones), 3 demonstrated effect on learning and behavior. Specifically, telenovelas increased knowledge and intention to change behaviors about breast cancer screening18 and among end-stage renal disease caregivers19; increased knowledge and willingness to consider using home care services11,20; and decreased stress and depression among dementia caregivers.21 The use of videos has been shown to be effective in educating about advanced care planning22,23 and in provoking medical questions to arouse.24 This suggests that videos can serve as a vehicle through which modifications can be made to medical treatment decisions24 and engagement in conversations about concerns can lead to better understanding of their distresses and provide necessary education.2

Conceptual Model and Telenovela Development Process

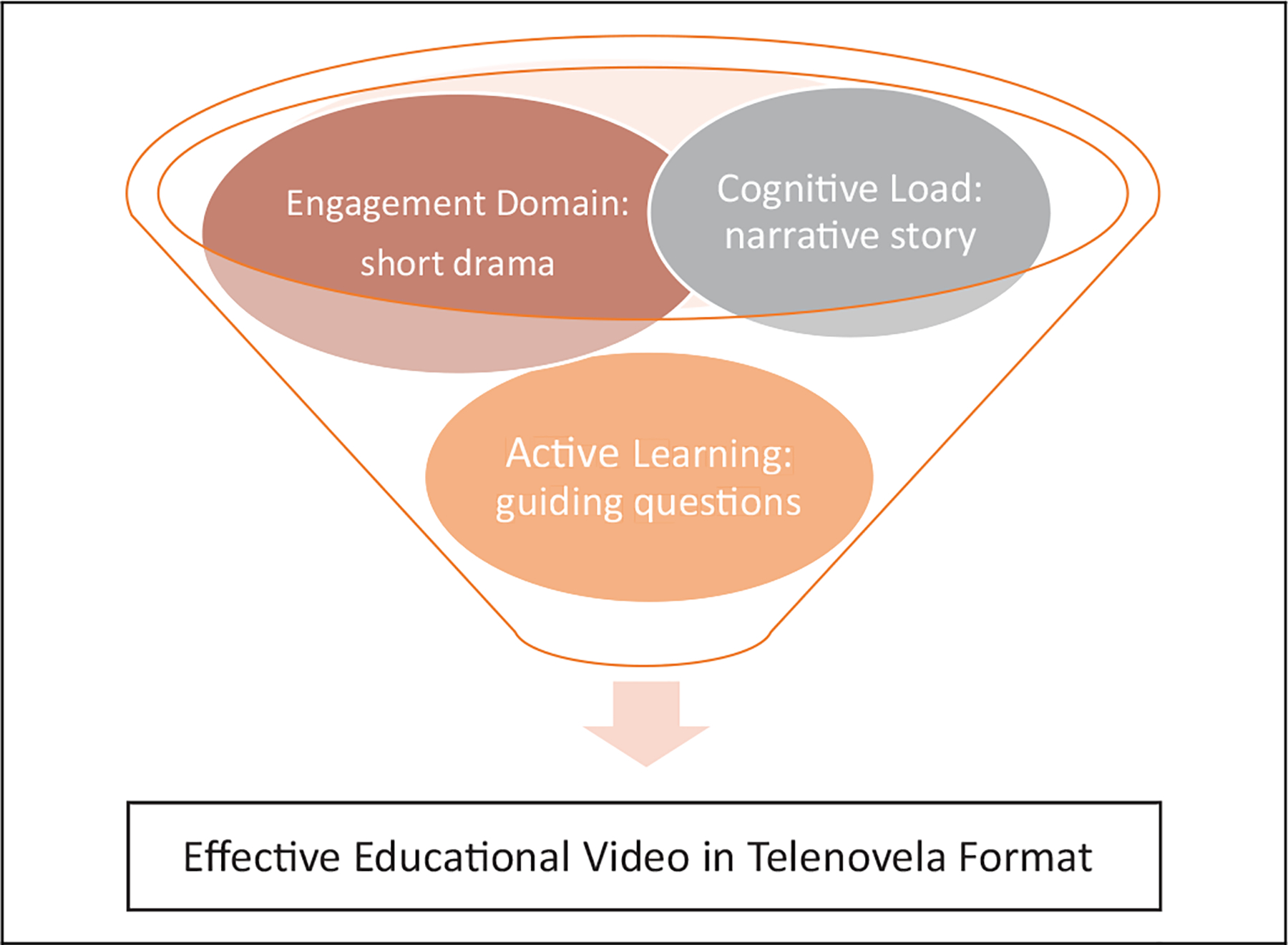

Following Brame’s25 suggestions for effective educational videos (see Figure 1) based on the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning,26 a script draft was created by one author (D.C.), then revised by experts (D.P.O. and A.V.), and edited into a telenovela script second draft. A bilingual author (D.C.) whose first language is Spanish translated the second draft. We used a 3-phase process to develop a 4-chapter telenovela video, 3 to 6 minutes long. The development process is summarized in Table 1, and Table 2 describes content of telenovela, To Care/El privilegio de cuidar.

Figure 1.

In order for video to serve as a productive part of a learning experience, it is important to consider three 3 elements for video design and implementation: cognitive load (Keep keep videos brief and use audio/visual elements to convey an explanation through narrative story); engagement (Highlight highlight important ideas or concepts and use a conversational, enthusiastic style through short drama); and active learning (Use use interactive elements or associated homework assignments through guiding questions).

Table 1.

Development of Telenovela, To Care/ El privilegio de cuidar.

| Phase and timeline | Purpose and steps | Implications for video development/assessment | Comments |

|

|

|

Content of video-recorded power point is based on preliminary work of interviews to hospice staff and caregivers to identify caregiver education needs |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

Field notes were taken to record feedback during research team and patient advisory board meetings. Focus groups and email interviews to a convenient sample of lay-people and family caregivers were also summarize into field notes. |

|

|

||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Table 2.

Details of Telenovela

| Video description | Content | Duration and learning objectives |

|---|---|---|

|

To Care This video soap opera (“telenovela”) is about a caregiver struggling to care for her loved one at home and how hospice help her learn about self-care, pain assessment, shared-decision making and the final journey |

The video contains 4 episodes, all of them developed at the house of the caregiver protagonist, Marinela Coki, the wife of the patient with cancer, Tom Coki. In the first episode, Marinela is receiving a visit from a hospice agency because her daughter, Betty, insisted she get more help given her poor health. The second episode shows her church neighbor, Roger, helping in the care of Tom, who later that night has a pain crisis. The third episode starts with Tom not responding and ends with Ricardo and Marinela discussing shared decision-making for his pain management. The last episode Marinela shares with Betty her realization of Tom’s imminent death. | 15:30 minutes MAIN MESSAGE: While caring for a loved one with terminal cancer... |

| ||

| ||

|

The content of the telenovelas has been widely found acceptable, but the appropriate dissemination is still a question. We decided to ask hospice professionals advice on the best method to disseminate the telenovelas. This study addressed the following research questions: (1) What is the reaction of hospice providers to the use of videos with telenovela format for educating family caregivers and (2) What suggestions do hospice providers have to disseminate telenovelas to their family caregivers.

Methods

Design

A semi-structured interview guide was designed by the study team following suggested questions from the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research guide.27,28 Hospice providers were asked about current use of technology and their perception of the potential use of videos for educating patients and family caregivers (see Table 3 for the interview guide). The study was approved by the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board.

Table 3.

Semi-Structured Interview.

| The next questions are related to a dramatic story we have designed to educate hospice caregivers. It is comprised of four 5-minute long stories emphasizing the importance of self-care, pain management, expectations for the final days, and shared decision-making. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Participants

Study participants were recruited using a voluntary response sample of hospice staff attending a state and national hospice conference in early October 2019. Hospice staff attending were asked to sign up if they were interested in participating in research and to provide contact information. Staff on the list were contacted via email and an appointment was made to interview them by telephone. Individuals provided verbal consent to participate in a 30-minute phone interview about their hospice experience and their thoughts regarding a new intervention for caregivers. If they agreed, they were given US$20 for their participation.

Data Collection

The study was conducted from October to December of 2019. Of 68 names on the list, 22 (32%) consented to participate. Two research staff trained by a senior researcher (D.O.) using standardized interview guide conducted all interviews, which were recorded and transcribed. The average length of interviews was 18 minutes (standard deviation: 5.93 minutes). Hospice staff characteristics were also collected, including, hospice profession, years of practice, hospice size and location; and the ways agency uses computers (email, billing, medical records, internet search, and patient/family education).

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were summarized using descriptive statistics. Although this was not a grounded theory study, we used elements of grounded theory including the constant comparative method, which allows analysts to move iteratively between codes and text to derive themes.29 Coding of transcripts involved sorting the data into large-level categories aligned with the interview guide and determined a priori. Two team members (D.C. and M.A.) independently coded transcripts using f4Analyse software, and suggested additional codes (eg, “fitting into existing processes”) that emerged in the interview. Detailed memos were kept throughout the coding process, and peer debriefing was used to assure trustworthiness as transcripts were discussed and discrepancies in coding were brought to consensus. Themes were derived through consensus during team meetings and data collection was completed when data saturation was reached.

Results

Characteristics of Hospice Staff Interviewed

A total of 22 hospice staff from 17 different hospices across 3 states agreed to participate and completed phone interviews. Most participants were nurses (36%) from hospice companies located mostly in Missouri (91%), with a mean of 9 years of experience. Irrespective of hospice size, all of the agencies used technology, but only 27% of them use it for patient/family education (see Table 4). Three discrete themes emerged: the background of hospice staff educational resources for patient/families, reasons for usefulness of videos, and practical suggestions of delivery.

Table 4.

Hospice Staff Sample Characteristics.

| Variable | Total (N = 22) |

|---|---|

| Profession, n (%) | |

| Nurse | 8 (36.4) |

| Social worker | 3 (13.6) |

| Chaplain | 3 (13.6) |

| Administrator | 3 (13.6) |

| Volunteer or coordinator | 5 (22.7) |

| Years of practice, mean ± SD (range 0.9–24.0) | 9.0 ± 7.2(30) |

| Hospice size, n (%) | |

| <50 | 11 (50.0) |

| 50–100 | 4(18.2) |

| >100 | 7 (31.8) |

| Agency technology use, n (%) | |

| 21 (95.5) | |

| Billing | 20 (90.9) |

| Medical record | 17 (77.3) |

| Internet search | 15 (68.2) |

| Patient/family education | 6 (27.3) |

| Missing | 1 (4.5) |

| Hospice company location, n (%) | |

| Missouri | 20 (90.9) |

| Other (Oklahoma and North Carolina) | 2 (9.1) |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Background of Hospice Staff Educational Resources for Patients/Families

Although hospice staff themselves provided significant individualized teaching, they had few resources to leave with families or to decrease staff workload. Participants described largely paper-based educational resources as the primary vehicle for addressing self-care needs among caregivers of hospice patients. Their use of technology as part of family teaching varied, with only 5 of 17 hospice programs using technology for patient/family education.

Right now, I currently have it all printed out in a book, not probably in full detail like a video would show. And we refer to that manual a lot when we’re in the home. I actually pack one with me, all the nurses do and social workers, because a lot of times they can’t find it. It’s just a fluster and they can’t find it.

(Staff #012)

Reasons for Usefulness of Videos

After hearing a description of the telenovela, participants shared perspectives on the utility of such videos. Participants acknowledged multiple ways that videos would contribute to improved education of family caregivers. Hospice staff were highly motivated to provide resources while reducing the emotional burden and sense of overwhelm that families experience as their loved one is dying. They described caregivers with extreme emotional, expectation, and learning needs. Many stated they thought videos would engage family members who could not focus on reading or who were too overwhelmed to sit down and go through a paper-based booklet. Additionally, the videos would provide a resource for family members who are more auditory learners, visual learners, or who have lower literacy levels. Finally, participants saw potential for the videos to serve as reminders regarding self-care to the staff as well while using the videos as a teaching aid could also reduce teaching burden.

Yes. I do see a need for that [videos], especially when we’re talking about expectations. Because I think that’s where there’s challenges with anyone that’s working in a hospice is everyone’s expectations versus what is the reality of it. And I think video is just another way. We all learn differently and we all receive that information differently, so I think that’s just another way that someone might hear it better, getting the information that way. I think that’s a great idea.

(Staff #010)

Finally, hospice staff also raised concerns about hindering hospice care because caregivers are overwhelmed and are interested in supportive resources rather than informational videos.

“Okay, now. Watch these videos,” it may feel to some people like … it may just feel like too much, and they’re not willing to think about the fact that this means what it means. They’re just wanting to get extra support and care for their loved ones …

(Staff #002)

Practical Suggestions for Delivery

While participants were encouraging of the opportunity to use an educational video such as the telenovela, they stressed the importance of appropriate implementation. Most important to hospice staff was the discussion around being sensitive to the needs of the family. They liked that the videos could be provided in multiple formats, so that when the family is ready to watch the videos they can, rather than overloading the families at the time of the staff visit. Suggestions for optimal timing ranged however from during the intake/admission process (n = 2), informational visits (n = 2), to during the social worker visit (n = 1). They suggested providing options for delivery including internet-based links, links provided in email, and providing DVDs, based on the preference of the family. They also highlighted the variation between the access to internet for rural versus urban populations and discussed that despite the prevalence of smartphones, that older family caregivers may prefer DVD.

So, I see with home patients, a much greater benefit to the technology. First of all, home patients are typically more awake, alert, oriented, wanting to receive education, wanting to learn all that they can about their disease progression. And so, having that equipment and those educational tools available I think is very beneficial for the patient and for their families. And so, when their families come to visit, they can all see the same video or it can be emailed to the different family members.

(Staff #018)

Less than half (n = 7) of participants suggested watching the videos with a hospice staff member present, but only 2 advised against in-person delivery of videos.

Well, yeah, I think the DVD, anything that you could place in their hand, because a lot of folks are resistant to it at the time of conversation. But if you can leave something in their home and give them that control and you look at it at your convenience, you’ve just handed them the control now you’re not pushing it on them … They may not do it when you want them to do it, but they’ll do it when this comfortable for them. And they can watch it over and over and over. That’s the other thing. I like the younger population, I know that I can speak to what’s going on now, but I also know what’s coming. And that’s a very much a younger generation of caregivers. They may really like that YouTube.

(Staff #014)

Of those who thought that a video would be advantageous, most thought the purpose would be to answer questions and continue to support family coping. Based on the various structures of hospice organizations recruited, different staff were suggested as the best fit to present this content. Some thought that different team members should be assigned to present different video topics (n = 3). Others thought that a social worker (n = 2), social worker and chaplain (n = 2), or social worker and nurse (n = 2) should deliver the content.

And that they are encouraging the team and whichever team members in particular, “Hey nurse, can you watch this one when you go next time? Hey chaplain, can you take this one? Social worker … ” Maybe even assigning them as something we do. I think that would be helpful.

(Staff #002)

We also inquired about what leadership would need to be engaged in each organization to begin using telenovela in family teaching. All participants identified multiple leaders who would need to be engaged to provide this type of education and that crucial leadership considerations would include cost of materials, cost to train staff, and staff time required to educate using the videos. Also, a few participants mentioned that the videos may need to be reviewed by their marketing department or for compliance to organizational standards.

I was just seeing the importance of it and [ … ] I guess if there was a cost to it, it would be seeing if we could purchase them. [ … ] That would be the, the clinical director or the director of medicine and the administrator and your nursing staff. If they are going to be the ones primarily showing the videos, they would probably need to watch them first, [ … ] and be able to speak to them or understand what potential questions [ … ] patients may have.

(Staff #016)

Discussion

This research explored the feasibility of using these videos and successful implementation strategies from the perspectives of hospice staff. To date, this is the first study looking at the development and use of telenovela for hospice care. Hospice agencies usually provide counseling and support services (eg, respite care) for family caregivers during life-threatening illness and after death of patient. However, many hospice agencies have not developed adequate resources to prepare caregivers for symptom management.2 While participants in our study reported little use of technology for patient/family education, they favored the use of telenovela video for family caregiver education and deliberation efforts.

In our study, hospice providers reported that visual learners will benefit the most from videos, and they may provoke conversations with family caregivers. Studies have reported that when participants can identify with the video, learning through modeling can take place,30,31 and participants value the visual as opposed to words or text.22 It is difficult to construct preferences where we have few prior experiences or only limited understanding of potential futures states. Narrative methods can play an important role in constructive preferences, given their ability to vividly portray procedures, experiences, and states.32 At the same time, the hospice staff serve as the behavioral component that helps caregivers cognitively internalize and emotionally process the information received to obtain confidence and tactics for active participation.33 Therefore, our research provides an innovative tool (namely, telenovela) to integrate into hospice care for family caregivers and this in turn would result in improvement of caregivers’ education and engagement with hospice providers.

Our study suggests that the telenovela video could be delivered in-person by hospice staff to family caregivers who are interested, and a link could be provided to watch it again or at a time that is more convenient. Similarly, other studies have reported that the usefulness of videos depends on the preferences (printed vs web-based information) and personality of each person,31 and the level of physical and psychological burden.2 The telenovela evaluated in this study was developed systematically with a strong theoretical basis for future implementation in routine hospice care. Future interventions studies could consider using telenovela video as an intervention delivery tool and explore which caregiver and at what moment would be best to offer.

This study has limitations. The sample in this study was small and based on convenience sampling. Detailed demographic data, including socioeconomic status and ethnicity or race, were not gathered from all participants, thus further limiting generalizability of this study. Participants could not watch the telenovela video, given the limitations of a telephone interview thus evaluation of video content was not possible. However, thorough video content evaluation was performed during development of telenovela video, which included hospice staff feedback.

Conclusion

Hospice staff reported that telenovela videos are a promising idea for education. They suggested that dissemination involves conversations between the staff and family during initial or routine hospice care visits. In addition, this study showed that hospice staff welcome and need technology-based comprehensive and clinically applicable resources to support family care-givers. Furthermore, hospice staff want to have a resource that can be integrated into their practices to prepare family care-givers for the difficulties of the hospice caregiving experience.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the Lab for Caregiving Innovation for supporting the work of Lucas Jorgensen, Christy Merrick, and Abeba Lakew in this project. The authors would also like to thank the patient advisory board at the University of Missouri Patient Outcomes Research Center, Angel Pacheco Rueda, medical student, and Dr Liliana Viera-Ortiz, palliative physician at University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences campus, for their input and assistance with video development.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute and award number R01CA203999 (Parker Oliver) through a Diversity Supplement. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.National Academies of Sciences E, and Medicine. Report in Brief: Families Caring for an Aging America: The National Academies Press; Published 2016. Accessed September 11, 2019 http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2016/Caregiving-RiB.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chi NC, Han S, Barani E, et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a pain management manual for hospice providers to support and educate family caregivers. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(3):207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker Oliver D, Albright D, Washington K, et al. Hospice care-giver depression: the evidence surrounding the greatest pain of all. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2013;9(4):256–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillick MR. The critical role of caregivers in achieving patient-centered care. JAMA. 2013;310(6):575–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wittenberg-Lyles E, Demiris G, Parker Oliver D, Washington K, Burt S, Shaunfield S. Stress variances among informal hospice caregivers. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(8):1114–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell JF, Whitney RL, Young HM. Family caregiving in serious illness in the United States: recommendations to support an invisible workforce. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(S2):S451–S456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quintiliani LM, Murphy JE, Buitronde la Vega P, et al. Feasibility and patient perceptions of video declarations regarding end-of-life decisions by hospitalized patients. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(6):766–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volandes AE, Levin TT, Slovin S, et al. Augmenting advance care planning in poor prognosis cancer with a video decision aid: a preintervention-postintervention study. Cancer Am Cancer Soc. 2012;118(17):4331–4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Mitchell SL, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a video decision support tool for cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision making in advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(3):380–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Jawahri A, Podgurski LM, Eichler AF, et al. Use of video to facilitate end-of-life discussions with patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):305–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crist JD, Pasvogel A, Hepworth JT, Koerner KM. The impact of a telenovela intervention on use of home health care services and Mexican American older adult and caregiver outcomes. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2015;8(2):62–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cruz-Oliver DM, Malmstrom TK, Fernandez N, Parikh M, Garcia J, Sanchez-Reilly S. Education intervention “caregivers like me” for Latino family caregivers improved attitudes toward professional assistance at end-of-life care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33(6):527–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chi NC, Demiris G. A systematic review of telehealth tools and interventions to support family caregivers. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21(1):37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruz-Oliver DM, Pacheco Rueda A, Viera-Ortiz L, Washington KT, Parker Oliver D. The evidence supporting educational videos for caregivers of patients receiving hospice and palliative care: a systematic review [published online March 19, 2020]. Patient Educ Couns. 2020: S0738–3991(20)30148–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Washington KT, Oliver DP, Benson JJ, et al. Factors influencing engagement in an online support group for family caregivers of individuals with advanced cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2020; 38(3):235–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cueva M, Kuhnley R, Lanier A, et al. Promoting culturally respectful cancer education through digital storytelling. Int J Indig Health. 2016;11(1):34–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cueva M, Kuhnley R, Slatton J, Dignan M, Underwood E, Landis K. Telenovela: an innovative colorectal cancer screening health messaging tool. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72:21301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkin HA, Valente TW, Murphy S, Cody MJ, Huang G, Beck V. Does entertainment-education work with Latinos in the United States? Identification and the effects of a telenovela breast cancer storyline. J Health Commun. 2007;12(5):455–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forster M, Allem JP, Mendez N, Qazi Y, Unger JB. Evaluation of a telenovela designed to improve knowledge and behavioral intentions among Hispanic patients with end-stage renal disease in Southern California. Ethn Health. 2016;21(1):58–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crist JD. Cafecitos and telenovelas: culturally competent interventions to facilitate Mexican American families’ decisions to use home care services. Geriatr Nurs. 2005;26(4):229–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kajiyama B, Fernandez G, Carter EA, Humber MB, Thompson LW. Helping Hispanic dementia caregivers cope with stress using technology-based resources. Clin Gerontol. 2018;41(3):209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deep KS, Hunter A, Murphy K, Volandes A. “It helps me see with my heart”: How video informs patients’ rationale for decisions about future care in advanced dementia. Patient Edu Couns. 2010; 81(2):229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volandes AE, Ariza M, Abbo ED, Paasche-Orlow M. Overcoming educational barriers for advance care planning in Latinos with video images. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(5):700–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein AS, Shuk E, O’Reilly EM, Gary KA, Volandes AE. ‘We have to discuss it’: cancer patients’ advance care planning impressions following educational information about cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Psycho Oncol. 2015;24(12):1767–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brame CJ. Effective Educational Videos Nashville. Vandelbilt University Center for Teaching; Published 2015. Accessed March 12, 2020 http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/effective-educational-videos/ [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayer RE, Moreno R. Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educ Psychol. 2003;38(1):43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50(3):217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) Ann Arbor. MI CFIR Research Team-Center for Clinical Management Research; 2020. https://cfirguide.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boeije HA purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Qual Quant. 2002;36(4):391–409. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung K, Augustin F, Esparza S. Development of a Spanish-language hospice video. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017;34(8):737–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leow MQH, Chan SWC. Evaluation of a video, telephone follow-ups, and an online forum as components of a psychoeducational intervention for caregivers of persons with advanced cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14(5):474–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Volandes AE, Edwards A, Montori VM. Investing in deliberation: a definition and classification of decision support interventions for people facing difficult health decisions. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(6):701–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Street RL Jr. Aiding medical decision making: a communication perspective. Med Decis Making. 2007;27(5):550–553.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]