Abstract

Phyllanthus amarus has been exploited for the management of several aliments in folkloric medicine. The present study therefore investigates the restorative potential of its leaves extract on hepatic and renal assault induced by CCl4 and rifampicin respectively. Eight groups (I-VIII) containing five animals each were created for the experiments. Group I were fed with normal commercial pellet only, while group II were exposed to single intraperitoneal injection of 3 ml/kg b.w. of CCl4 only. Groups III, IV and V animals were administered 3 ml/kg b/w of CCl4 and treated with 50, 100 mg/kg b. w. of P. amarus and 100 mg/kg b.w of silymarin respectively. Group VI animals were orally exposed to 250 mg/kg b/w of rifampicin only while groups VII and VIII were treated with 50 and 100 mg/kg b. w. P. amarus respectively for 14 days after the initial exposure to 250 mg/kg b/w rifampicin . Liver and kidney function tests such as alanine amino transferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), bilirubin, urea and uric acid were determined in the serum and organs homogenates. Moreover, malonidialdehyde (MDA), catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione (GSH) as well as lipid profile were also measured. Results showed that exposure to rifampicin and CCl4 respectively caused a marked derangement in lipid profile as well as decrease in SOD and CAT activity relative to the negative control. Administration of both toxicants also caused a marked increase in serum ALT, AST, ALP, urea, uric acid and creatine kinase compared to the negative control. Treatment with P. amarus attenuated the toxicity imposed by rifampicin and CCl4 on the liver and kidney in a dose-dependent fashion. All biochemical indices measured were restored to values comparable with animals treated with silymarin. Histopathological results of the hepatic and renal tissues from the various groups of experimental animals gave credence to the curative effects of P. amarus leaf extract on damaged liver and kidney cells. Put together, P. amarus is a potential medicinal plant with similar potency to conventional drugs currently in use for the treatment liver and kidney diseases. Hence, it is a viable therapeutic alternative that can be exploited for the treatment of renal and hepatic diseases.

Keywords: P. amarus, Liver, Kidney, Medicinal, Rifampicin, Carbon tetrachloride, Biochemistry, Biological sciences, Health sciences, Organ system, Pathophysiology, Toxicology

P. amarus; Liver; Kidney; Medicinal; Rifampicin; Carbon tetrachloride; Biochemistry; Biological sciences; Health sciences; Organ system; Pathophysiology; Toxicology

1. Introduction

Medicinal plants have been recognized as veritable therapeutic agents since they house a cocktail of secondary metabolites (phytochemicals) with vast medicinal benefits (Sandberg and Corrigan, 2001). Plants with medicinal potentials are useful both as raw materials for the maintenance of sound health as well as in the treatment of diseases (Schulz et al., 2001; Calixto, 2000). Consequently, the role of plant-based drugs for alleviating and/or eradicating diseases is increasing globally (Bhat, 2014).

The etiology of almost all diseases have been linked to deleterious imbalance between free radicals production and the body's antioxidant capacity to neutralize them. Whenever reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced in excess of the endogenous antioxidant capacity to mop them, oxidative stress becomes inevitable. During oxidative stress, free radicals wreck havoc on critical macromolecules such as protein, nucleic acids, lipids and carbohydrates. This oxidative attack ultimately results in pathological conditions depending on the organs attacked (Alugoju et al., 2015).

Phyllanthus amarus (Euphorbiaceae) is an annual tropical plant with several medicinal benefits in folkloric medicine. Several reports have shown that P. amarus exhibits numerous medicinal properties including: antihepatitis (Thyagarajan et al., 1988), antimalarial (Tran et al., 2003), anti-viral (Notka et al., 2004; Pramyothin et al., 2007; Burkill, 1994)), antibacterial (Mazumder et al., 2006), antidiarrheal (Odetola and Akojenu, 2000) as well as in the treatment of several skin infections (Adeneye et al., 2006; Kassuya et al., 2005). It possesses hepatoprotective (Toyin et al., 2008; Raphael et al., 2002b; Kumar and Kuttan, 2005) anti-carcinogenic (Rajeshkumar et al., 2002), anti-inflammatory (Kiemer et al., 2003), antiasthmatic (Oluwafemi and Debiri, 2008; Idowu et al., 2009) and antidiabetic (Raphael et al., 2002) properties. Considering the vast medicinal relevance of the plant coupled with the challenge of an ever-increasing burden of liver and kidney diseases in developing nations, such as Nigeria, there is a dire need to evaluate the medicinal potentials of P. amarus leaves that can be exploited as a viable, cheap and efficient alternative to conventional drugs currently used in the management of renal and hepatic diseases.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of plant extract

P. amarus leaves were obtained from a private farm in Ado Ekiti, botanically identified and authenticated at the Department of Plant Science, Ekiti State University, Ado Ekiti. Its voucher specimen with number UHAE2020072 was deposited at the university herbarium. Its leaves were then air-dried, pulverized, weighed and stored in an airtight container.

325 g of the powdered leaves was extracted in 1000 ml of 80% (v/v) ethanol for 72 h. The mixture was then filtered on cheese cloth to get the supernatant which was kept in an airtight container and residue that was discarded. The crude extract was obtained from the filtrate by freeze-drying, weighed and kept in an airtight container in the refrigerator. Subsequently, the crude extract was reconstituted with appropriate volume of distilled water and administered to experimental animals.

2.2. Reagents and chemicals

Adrenaline, malonidialdehyde (MDA), phosphotungistic acid, magnesium acetate, creatine phosphate, potassium phosphate, hydrogen peroxide, ethylene diamine tetraacetate (EDTA), Ellman's reagent and reduced glutathione (GSH). Other chemicals and reagents used were of high grade analytically and were obtained from reputable commercial suppliers. All biochemical kits were obtained from Randox Chemical Ltd. England.

2.3. Animals protocol

All experimental animals were used in accordance with established guidelines (Revised NIH Publications 1978, No. 8023) and ethical approval of the Committee on Care and Use of Experimental Animal Resources, College of Medicine, Ekiti State University, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria. Forty wistar albino rats with mean weight of 170 g were purchased from the animal breeding colony of the Department of Science Technology, Federal Polytechnic, Ado - Ekiti. Eight groups of five animals per group were created as described in Table 1. Experimental animals were accomondated in separate cages made of iron- meshed at ambient temperature (24 ± 1 °C), relative humidity, and 12/12-h light and dark cycle. Animals were given unrestricted daily access to food and drinking water ad libitum. Throughout the experimental period, rat beddings were routinely turned-over on a daily basis to maintain good hygiene.

Table 1.

Animal treatment.

| Groups | Treatment |

|---|---|

| I: Negative Control (PC) | Distilled water only |

| II: Positive Control (NC) | 3 ml CCl4 single administration |

| III | 3 ml CCl4 + 50 mg/kg b.w P. amarus |

| IV | 3 ml CCl4 + 100 mg/kg b.w. P. amarus |

| V | 3 ml CCl4 + 100 mg/kg b.w. Silymarin |

| VI | 250 mg/kg b.w. rifampicin alone for a single administration |

| VII | 250 mg/kg b.w. rifampicin + 50 mg/kg P. amarus |

| VIII | 250 mg/kg b.w. rifampicin + 100 mg/kg P. amarus |

2.4. Dissection of rats

Decapitation of animals was done under cold ether anesthesia and rapidly dissected to excise the liver and kidney which were separately trimmed of fat. The tissues were washed in distilled water, and blotted with clean filter paper, weighed and homogenized in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) to obtain a 10% homogenate. The resulting homogenates were centrifuged separately at 3000 rpm at 4 °C for 30 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was decanted and kept chilled by refrigeration. Whole blood was obtained by cardiac puncture into an EDTA bottle and left to stand for 1 h at room temperature. Serum was obtained from the whole blood by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 15 min at 25 °C. The serum was then obtained as supernatant and refrigerated for subsequent estimation of serum biochemical parameters.

2.5. Assay for creatine kinase (Ck-Mb) activity

Creatine kinase activity was assayed according to Reitman and Franke (1957). One milliliter of imidazole buffer containing: 2.0 mM nicotinamide adenine diphosphate, 10 mM imidazole pH 6.6, 20 mM glucose, 30 mM creatine phosphate, 20 mM N-acetyl-cysteine, 2.0 mM ethylene diaminetetraacetate, 2.0 mM adenosine diphosphate, 5.0 mM adenosine monophosphate, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 10 μM DAPP, 2.0 ku/L glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and 2.15 ku/L hexokinase was pipetted into a thermostatic cuvette and heated to 37 °C. This was followed separate addition of 50 μl each of serum and tissues homogenates and thorough agitation of the resulting mixture. Absorbance at 340 nm was read immediately for 5 min at 30 s interval, followed by the estimation of the change in absorbance per min.

2.6. Measurement of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) activity

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) activity was assayed following the method of Reitman and Franke (1957). One hundred microliter each of serum, liver and kidney was added to phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4), α-oxoglutarate (2 mM) and L-aspartate (100 mM). The resulting mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Five hundred microliter of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (0.02 M) was then added to the reaction mixture and left for 20 min at 25 °C. Five milliliter of 0.4 M NaOH was then introduced to the mixture and its absorbance at 546 nm was read after 5 min against the reagent blank.

2.7. Measurement of alanine amino transferase (ALT) activity

ALT activity was measured following the method of Reitman and Franke (1957). Five hundred microliter of reagent 1 (R1) made up of 100 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 2.0 M α-oxoglutarate and 0.2 M L-alanine were added separately to 0.1 mL of serum and tissues homogenates in different test tubes and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Five hundred microliter of reagent 2 (R2) made up of 0.02 M 2, 4-dinitrophenylhydrazine was then added and the resulting solution re-incubated for 20 min at 20 °C. Finally, 5.0 ml of NaOH was added to the reaction mixture and left to stand for 5 min at 25 °C. Absorbance of the resulting solution was then read at 546 nm.

2.8. Assay for akaline phosphatase (ALP) activity

ALP activity in the tissue homogenates as well as the serum was determined according to the method of Englehardt (1970) using biochemical assay kits (Randox laboratories, UK). One milliliter of reagent A made up of 0.5 mM MgCl2, 1.0 M diethanolamine buffer pH 9.8, substrate and 10 mM p-nitrophenol phosphate, was added separately to 0.02 mL of liver, kidney and heart homogenates and thoroughly mixed. Absorbance of the assay mixture was then monitored at 405 nm for 3 min at 1 min interval.

2.9. Serum lipid profile analysis

2.9.1. Total cholesterol

Total cholesterol level in the tissues homogenates and serum was estimated according to the method of Trinder (1969) using commercially available kits from Randox laboratories, United Kingdom. Ten microlitres each of cholesterol standard, serum and tissues homogenates were measured into separate test tubes with labels. One milliliter of working reagent made up of: 0.25 mM 4-Aminoantipyrine, 0.08 M Pipes buffer pH 6.8, 6.0 mM phenol; 0.5 U/mL peroxidase; 0.15 U/mL cholesterol esterase ion and 0.10 U/mL cholesterol oxidase was measured into all the tubes. After thorough mixing, the test tubes were incubated for 10 min at 25 °C. Absorbance of sample (Asample) was read at 500 nm against the reagent blank. Total cholesterol (mg/dl) was then estimated (1)

| (1) |

2.9.2. Determination of triglyceride concentration

Levels of triglycerides in the tissue homogenates and serum was determined based on Tietz (1995). Ten microliter each of triglyceride standard, serum, kidney and liver homogenates was measured into test tubes with labels. Thereafter, 1.0 mL of working reagents; R1a (buffer) containing 17.5 mM magnesium-ion, 40 mM Pipes buffer pH 7.6; 0.0055 M 4-chlorophenol and enzyme reagent (R1b) which consists of 1.0 mM ATP, 0.4 U/mL glycerol-kinase, 0.5 mM 4-amino phenazone; 150 U/mL lipase, 0.5 U/mL peroxidase and 1.5 U/mL glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase and was measured into the labelled test tubes. The mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 10 min after thorough mixing. Absorbance of the reaction mixture was then measured at 546 nm against the blank. Concentration of triglyceride (mg/dL) was then estimated (2)

| (2) |

2.9.3. High density lipoprotein (HDL-c)-cholesterol

Amount of HDL-c in the tissues and serum was determined following the method of Grove (1979). Reaction mixture containing 200 μL each of tissue homogenates, serum, and the cholesterol standard was mixed with 500 μL of the diluted precipitant R1 (0.55 mM phosphotungstic acid, 25 mM magnesium chloride) and left for 10 min at 25 °C. The reaction mixture was then centrifuged for 10 min at 4000 rpm. The clear supernatant obtained was decanted within 2 h and its cholesterol content was estimated by the CHOD-PAP reaction method as described below:

One thousand microliter of cholesterol reagent was measured and thoroughly mixed with 100 μL each of tissue homogenates and serum in separate test tubes. Contents of the test tube (1 mL of cholesterol reagent and 100 μL each of the cholesterol standard and supernatant) labelled as standard was thoroughly mixed and incubated at 25 °C for 10 min. Absorbance of the sample (A sample) and standard (Astandard) was then read within 1 h at 500 nm against the reagent blank.

2.9.4. Low density lipoprotein (LDL) - Cholesterol

Low-density lipoprotein in the tissue homogenates as well as serum was estimated using Eq. (3) of Friedwald et al. (1972).

| (3) |

2.10. Assay for catalase (CAT)

Catalase activity in the liver, kidney and serum of experimental animals was done by the method of Sinha (1972). Two hundred microliters each of five fold dilution of serum, kidney and liver homogenates serum was measure into a reaction mixture of 2 mL of (800 μmol) hydrogen peroxide and 2.5 mL of potassium phosphate buffer. Five hundred microliter of appropriate enzyme dilution was rapidly introduced to with the mixture and agitated by gentle swirling in a flat bottom flask at 25 °C. One milliliter aliquot of the reaction mixture was withdrawn and blown into 1 mL dichromate/acetic acid reagent at 60 s intervals. Catalase activity was estimated as the amount of hydrogen peroxide consumed per minute per mg protein (4).

| H2O2 consumed = 800 – Concentration of H2O2 remaining | (4) |

Concentration of H2O2 remaining was extrapolated from the standard curve for catalase activity.

2.11. Assay for superoxide dismutase (SOD)

SOD activity was measured according to Misra and Fridovich (1972). An aliquot of a 10 fold dilution each of serum, liver and kidney homogenates was measured into 2.5 mL of 0.05 M carbonate buffer (pH 10.2) and left to for equilibration in the spectrophotometer. 0.3 mM of freshly prepared adrenaline was added to the mixture agitated by rapid inversion to initiate enzymatic reaction. The blank contained all other components of the assay mixture except the enzyme (serum and tissue homogenates) which was replaced with distilled water. Absorbance of the mixture was monitored at 480 nm was monitored for 150 s at 30 s interval.

2.12. Estimation of reduced glutathione

Concentration of reduced glutathione (GSH) in the liver, kidney and serum was measured by the method of Beutler and Kelly (1963). Two hundred microliter of homogenates, 1.8 mL distilled water and 3 mL of precipitant were thoroughly mixed, incubated for 5 min at 25 °C and filtered. One milliliter of five fold dilution of the filtrate then mixed with 0.5 ml of Ellman's reagent. The blank consists of all other assay components except the homogenates. Absorbance of the resulting solution was read at 412 nm against the blank.

2.13. Lipid peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation in the homogenates and serum of experimental rats was determined as described by Ohkawa et al. (1979)Ohkawa et al. (1979) using Randox kits. One hundred microliter each of kidney and liver homogenates as well as serum were mixed separately with 2.5 mL reaction buffer and incubated for 1 h at 100 °C. After cooling, the mixture was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min and decanted to obtain a supernatant. Absorbance of the supernatants was then read at 532 nm. Malonidialdehyde (MDA) level in the supernatant was expressed as μmole MDA per mg protein taking the molar absorptivity of MDA-thiobarbituric chromophore as 1.56×105/M/cm.

2.14. Estimation of urea, uric acid and total bilirubin

Amount of urea was determined by the method Veniamin and Vakirtz (1970). Total bilirubin was measured according to the diazonium salt method of Winsten and Cehelyk (1969). Uric acid level was determined using the uricase-peroxidase method by Fossati et al. (1980).

2.15. Estimation of total protein

Total protein in the tissue homogenates and serum was measured by Weichselbaum (1946) using commercially available kits (Randox laboratories, UK). One milliliter of Reagent R1 made up of sodium hydroxide (100 mM), Na–K-tartrate (18 mM), potassium iodide (15 mM) and cupric sulphate (6 mM) was mixed with 0.02 mL of the homogenates and incubated at 25 °C. Absorbance of the mixture was measured at 546 nm.

2.16. Statistical analysis

All experimental data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Dat were analyzed using One Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan's Multiple Range Test (DMRT) by using SPSS 11.09 for windows. Level of significance was at p < 0.05.

3. Results

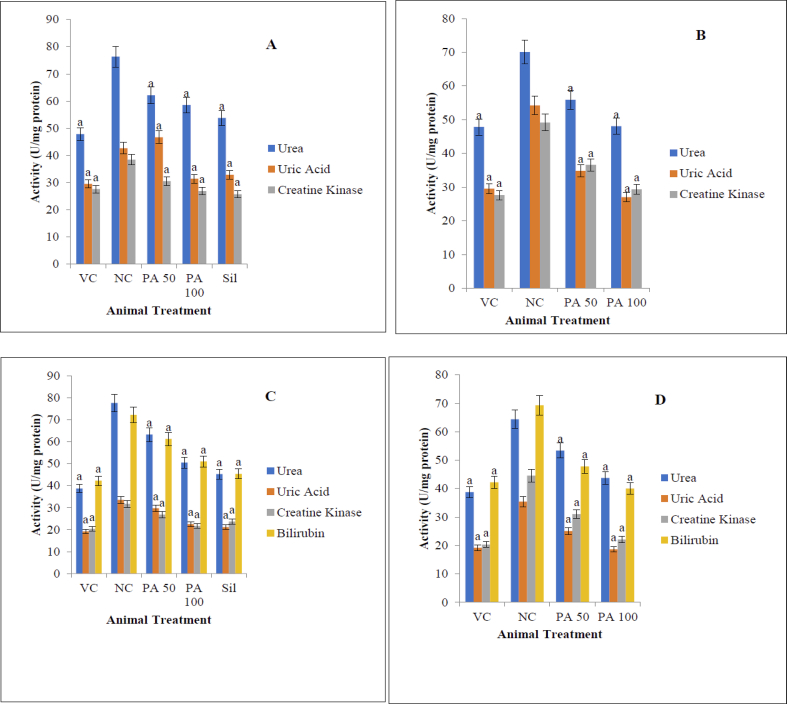

Generally, results indicate that both CCl4 and rifampicin are toxic to both liver and kidney (Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4). P. amarus extract restored enzymatic activity of catalase, superoxide dismutase and creatine kinase which were initially lost after exposure to the toxicants (Table 2). Restoration was dose dependent and comparable to animals treated with standard drug (Table 2). Similarly, administration of CCl4 and rifampicin respectively caused a marked derangement of lipid profile (triglycerides, low density lipoproteins (LDL), cholesterol and high density lipoprotein (HDL)) in experimental animals (Table 2). However, treatment with P. amarus extract reversed the derangement to a level comparable with the negative control and animals treated with silymarin respectively. Biomarkers of liver (AST, ALT, ALP, Total bilirubin) (Figure 1) and kidney (creatine kinase, urea and uric acid) (Figure 2) were significantly raised in the animals administered with CCl4 and rifampicin without treatment. Treatment with P. amarus leaf extract reversed the trend by restoring values of these biomarkers to that comparable with animals treated with silymarin (Figure 2). Reduced glutathione (GSH) which was depleted by exposure to CCl4 and rifampicin respectively were raised back to values similar to negative control animals (Table 2) after treatment with P. amarus leaf extract. Finally, lipid peroxidation was markedly inhibited in a dose-dependent fashion by treatment with P. amarus extract (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Effect of P. amarus leaf extract on ALT, AST, ALP and total bilirubin of albino rats exposed to CCl4 and rifampicin toxicity. Data represents mean ± SEM values of four independent experiments performed in triplicate. ‘a’ represents significant difference (P<0.05) from the positive control - (NC); VC - negative control; PA - P. amarus; Sil - Silymarin. Rif – Rifampicin. ALP-  ALT-

ALT-  AST-

AST-  T.BIL-

T.BIL-  . A and B are liver of CCl4 and rifampicin - challenged rats respectively. C and D are kidney of CCl4 and rifampicin - challenged rats respectively; E and F are serum of CCL4 and rifampicin - challenged rats respectively.

. A and B are liver of CCl4 and rifampicin - challenged rats respectively. C and D are kidney of CCl4 and rifampicin - challenged rats respectively; E and F are serum of CCL4 and rifampicin - challenged rats respectively.

Figure 2.

Effect of P. amarus leaf extract on selected biomarkers of albino rats exposed to CCl4 and rifampicin toxicity. Data indicates mean ± SEM values of four independent experiments performed in triplicate. ‘a’ represents significant difference (p<0.05) from the positive control - (NC); VC - negative control; PA - P. amarus; Sil-Silymarin. C.K.-  Urea-

Urea-  Uric Acid-

Uric Acid-  Bilirubin-

Bilirubin-  . A and B are kidney of CCl4 and rifampicin-challenged rats respectively. C and D are serum of CCl4 and rifampicin-challenged rats respectively.

. A and B are kidney of CCl4 and rifampicin-challenged rats respectively. C and D are serum of CCl4 and rifampicin-challenged rats respectively.

Figure 3.

Effect of P. amarus leaf extract on lipid peroxidation in albino rats exposed to CCl4 and rifampicin toxicity. Data indicates mean SEM values of four independent experiments performed in triplicate. ‘a’ represents significant difference (p < 0.05) from the positive control - (NC); PC- negative control; PA- P. amarus; Sil- Silymarin. A and B represent animals challenged with CCl4 and rifampicin respectively.

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph of the liver Fig. (A–D) and kidney Fig. E–G) of albino rat under different experimental conditions. A- liver photomicrograph of negative control animals (fed with normal feed and distilled water only): Histomorphology of the hepatic tissue normal with distinct hepatocytic nuclei well positioned in their cytoplasmic space. There is no observable histopathological alteration in the liver tissues. B- liver photomicrograph of animals exposed to with 3 ml/kg CCl4: Cholestatic fatty liver was observed, with distorted hepatic histoarchitecture. C- liver photomicrograph of animals exposed to 3 ml/kg CCl4and treated with 100 mg/kg P. amarus: Normal liver histoarchitecture was noticed. There are no histopathological alterations in the histological presentation of the hepatic tissues. D - liver photomicrograph of animals exposed to 3 ml/kg CCl4and treated with 100 mg/kg Silymarin: The nuclei of hepatocytes are well stained and properly positioned in the cytoplasm. There are no histopathological alterations in the histological presentation of the liver tissues. E - kidney photomicrograph of animals exposed to distilled water only: There renal corpuscle was normal, with appropriate cellular delineation, distribution, density and staining intensity. No apparent histopathological alteration was observed. F - kidney photomicrograph of animals administered with 250 mg/kg rifampicin only: Normal renal histoarchitecture was distorted with glomerular atrophy. Renal tubular degeneration coupled with intraluminal exfoliation and granular cast formation as well as pyknosis of the nuclei were observed. G- kidney photomicrograph of animals exposed to 250 mg/kg rifampicin and treated with 100 mg/kg bw of P. amarus: Normal renal corpuscle with typical cellular delineation, distribution, density and staining intensity. No apparent histopathological alteration. CT - Convoluted tubule, GC- glomerular capillaries, P- podocytes, JC- juxtaglomerular cells MD- macula densa cells.

Table 2.

Effect of P. amarus leaf extract on lipid profile and other antioxidant parameter in the liver, kidney and serum of albino rats separately exposed to CCl4 and rifampicin toxicity.

| Parameters | Tissues | NC (distilled water only) | PC I (CCl4 Only) | CCl4 + (50mg/kg PA) | CCl4+ (100mg/kg PA) | CCl4+ (100mg/kg Silymarin) | PC II (Rif. Only) | Rif + (50mg/kg PA) | Rif + (100mg/kg PA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. chol (mg/dL) | Liver | 56.08±2.09a | 89.12±1.73b | 67.33±2.07c | 60.27±1.12d | 52.33±1.34e | 97.23±1.42b∗ | 65.14±1.06c∗ | 56.15±1.06d∗ |

| Kidney | 30.07±2.18a | 41.86±2.09b | 32.64±1.10c | 28.39±1.06d | 38.63±2.23e | 56.71±1.18 b∗ | 42.15±1.17 c∗ | 26.29±1.20 d∗ | |

| Serum | 52.16±2.19a | 72.44±1.86b | 63.04±1.23c | 57.69±1.63d | 58.27±1.56e | 87.46±1.38 b∗ | 68.44±1.20 c∗ | 55.36±1.11 d∗ | |

| Trig. (mg/dL) | Liver | 31.33±1.07a | 70.25±1.24b | 52.37±1.06c | 43.53±1.23d | 39.43±1.13e | 86.50±0.42 b∗ | 60.33±1.22 c∗ | 42.67±1.03 d∗ |

| Kidney | 11.82±0.34a | 19.47±0.42b | 16.49±0.75c | 12.68±0.34d | 13.43±0.29e | 38.68±1.18 b∗ | 31.55±1.25 c∗ | 24.58±1.21 d∗ | |

| Serum | 37.51±1.39a | 61.41±1.28b | 52.56±1.11d | 44.38±1.48d | 40.14±1.72e | 70.39±1.45 b∗ | 56.84±1.00 c∗ | 34.39±1.06 d∗ | |

| HDL (mg/dL) | Liver | 24.72±0.44a | 46.07±0.53b | 35.36±0.96c | 25.31±0.74d | 26.31±0.59e | 18.26±0.24 b∗ | 22.26±0.46 c∗ | 25.46±0.61 d∗ |

| Kidney | 8.26±0.17a | 5.31±0.87b | 6.32±0.59c | 7.86±0.54d | 8.42±0.68e | 3.07±0.02 b∗ | 4.06±0.08 c∗ | 4.59±0.01 d∗ | |

| Serum | 9.42±0.31a | 6.37±0.43b | 7.04±0.22c | 7.93±0.17d | 8.79±0.29e | 5.10±0.07 b∗ | 6.38±0.07 c∗ | 7.20±0.95 d∗ | |

| LDL (mg/dL) | Liver | 33.76±1.27a | 41.27±1.53b | 35.18±1.15c | 29.80±0.88d | 33.04±0.08e | 57.81±0.11 b∗ | 48.17±0.45 c∗ | 42.55±0.38 d∗ |

| Kidney | 13.26±0.73a | 21.60±0.82b | 17.54±0.42c | 14.83±0.36d | 12.13±0.48e | 22.74±0.27 b∗ | 17.28±0.15 c∗ | 14.32±0.12 d∗ | |

| Serum | 22.36±0.32a | 34.26±0.53b | 28.47±0.21c | 23.08±0.41d | 24.67±0.72e | 39.53±0.68 b∗ | 33.29±0.76 c∗ | 27.42±0.61 d∗ | |

| SOD (μmol /min) | Liver | 6.14±0.09a | 4.53±0.73b | 5.12±0.07c | 6.07±0.12d | 6.20±0.34e | 2.36±0.04b∗ | 4.19±0.06c∗ | 5.26±0.16d∗ |

| Kidney | 3.84±0.18a | 2.46±0.09b | 2.89±0.10c | 3.17±0.06d | 3.15±2.23e | 1.93±0.18 b∗ | 2.41±0.17 c∗ | 2.84±0.20 d∗ | |

| Serum | 4.29±0.19a | 3.17±0.16b | 3.55±0.23c | 4.24±0.63d | 4.34±0.15e | 2.42±0.13 b∗ | 3.93±0.20 c∗ | 4.62±0.14 d∗ | |

| CAT (μmol /min) | Liver | 4.70±0.07a | 2.89±0.24b | 3.82±0.06c | 4.14±0.23d | 4.45±0.13e | 1.63±0.42 b∗ | 1.93±0.22 c∗ | 4.07±0.03 d∗ |

| Kidney | 2.77±0.14a | 2.02±0.12b | 2.39±0.15c | 2.61±0.14d | 2.58±0.19e | 1.88±0.18 b∗ | 2.21±0.25 c∗ | 2.68±0.21 d∗ | |

| Serum | 3.06±0.13a | 2.38±0.28b | 2.89±0.11d | 2.86±0.18d | 2.93±0.12e | 1.76±0.14 b∗ | 2.97±0.10 c∗ | 3.10±0.06 d∗ | |

| GSH (μmol) | Liver | 5.77±0.27a | 3.87±0.13b | 5.41±0.15c | 5.81±0.18d | 5.43±0.08e | 2.93±0.11 b∗ | 3.86±0.15 c∗ | 5.14±0.18 d∗ |

| Kidney | 3.23±0.13a | 2.53±0.12b | 3.08±0.12c | 3.15±0.16d | 3.19±0.15e | 3.04±0.27 b∗ | 3.10±0.15 c∗ | 3.17±0.12 d∗ | |

| Serum | 2.66±0.32a | 1.57±0.13b | 1.90±0.21c | 2.23±0.11d | 2.49±0.17e | 2.08±0.18 b∗ | 2.28±0.16 c∗ | 2.37±0.11 d∗ | |

| T. Protein (mg/mL) | Liver | 2.64±0.08a | 1.47±0.09b | 2.07±0.10c | 2.25±0.06d | 2.33±0.03e | 1.04±0.08 b∗ | 1.66±10.07 c∗ | 2.38±0.20 d∗ |

| Kidney | 1.73±0.10a | 0.76±0.07b | 0.97±0.03c | 1.23±0.02d | 1.44±0.05e | 1.06±0.13 b∗ | 1.20±0.12 c∗ | 1.47±0.11 d∗ | |

| Serum | 2.08±0.13a | 1.26±0.05b | 1.74±0.13c | 1.95±0.12d | 2.17±0.15e | 1.02±0.31 b∗ | 1.42±0.20 c∗ | 1.91±0.11 d∗ |

Data shows mean ± SEM values of four independent experiments performed in triplicate. ‘a’, ‘c’, ‘d’ and ‘e’ represent significant difference (p<0.05) from (‘b’) and (‘b∗’) - positive controls (PCI and II); C∗ and d∗ represent animals treated with 50 mg/kg bw and 100 mg/kg bw of PA respectively after initial exposure to rifampicin toxicity; NC- negative control; PA- P. amarus; Rif- rifampicin.

4. Discussion

Globally, use of plants for prophylaxis and curative treatment of diseases is an age-long practice. Till date, a significant proportion of the world population depends on herbal preparations as drugs (Ogbera et al., 2010). P amarus is an ubiquitous plant that has been exploited in folkloric medicine due to its vast medicinal potentials (Ankur et al., 2011).

Exposure of experimental animals to CCl4 and rifampicin respectively resulted in multiple oxidative damages to kidney and liver cells. Biochemical and histopathological observations confirmed the oxidative damage. Biomarkers of liver injury including AST, ALT and ALP were markedly increased in the serum of albino rats following exposure to CCl4 and rifampicin. This indicates that both CCl4 and rifampicin triggered an increased production of ROS in excess of the endogenous antioxidant capacity to mop –up, thereby eliciting organ damage. However, treatment with P. amarus leaves extract caused a dose-dependent restoration of ALT, ALP and AST in fashion similar to the negative control animals and those treated with silymarin. This agrees with the report of Surya et al. (2011). Phytochemical screening of P. amarus has shown that it is rich in flavonoids, alkaloids, major lignans, hydrolysable tannins and polyphenols (Kassuya et al., 2005; Morton, 1981; Srivastava et al., 2008; Chevallier, 2000; Maciel et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2003). Earlier reports have shown that phyllanthin, a major lignan present in abundance in P. amarus leaves is responsible for attenuation of liver toxicity (Chirdchupunseree and Pramyothin, 2010; Krithika and Verma, 2009a,b; Yadav et al., 2008). In line with these reports, the restorative potential of P. amarus leaf extract used in the present study is attributable to phyllanthin. Noteworthy is the fact, that there was no significant difference in therapeutic efficiency between P. amarus extract at 100 mg/kg bw and silymarin at the same dose. This finding is in line with Igwe et al. (2007) who reported the restorative potential of methanolic extract of P. amarus (whole plant) in chemically induced hepatotoxicity.

Exposure to CCl4 and rifampicin resulted in an elevated lipid peroxidation, indicating that the major mechanism of toxicity of these compounds is via lipid peroxidation. Obviously, when free radicals are produced at a level beyond the antioxidant capacity of the system, they constitute a major threat to health. By virtue of their chemistry, free radicals are highly reactive because of an unpaired electron in the shell. In an attempt to gain stability, free radicals abstract protons from chemically stable macromolecules such as proteins, carbohydrates, nucleic acids and lipids, wrecking havocs. Polyunsaturated lipids, a major component of the biomembrane are more susceptible to ROS. Hence, an oxidative attack on membrane lipids could result in compromise of critical membrane functions. It has been suggested that malondialdehyde (MDA) produced during lipid peroxidation is responsible for organ damage (Arun and Balasubramanian, 2011; Lodhi et al., 2014; Das and Vasudevan, 2006). The present study established that, administration of P. amarus markedly restored the antioxidant capacity by inhibiting lipid peroxidation. Nikam et al. (2011) reported the antioxidant capacity of P. amarus to inhibit lipid peroxidation in ethanol-induced liver damage and attributed same to its high polyphenolic content. In line with this finding, inhibition of lipid peroxidation by P. amarus leaves extract is due to the presence of a wide array of polyphenols.

Reduced glutathione is an intracellular non-protein thiol that coordinates the biochemistry of antioxidants defense. It is the major source of cellular reducing power, acting as free radicals scavenger, thereby arresting oxidative stress. It is also the model substrate for major enzymes of phase II detoxification of xenobiotics. Routinely, level of GSH has been used to predict the health status of an organism. The present study indicates that, administration of CCl4 and rifampicin caused a significant depletion of GSH in the serum and tissue homogenates. This is an indication that the two compounds (CCl4 and rifampicin) at the stated doses generated enough ROS that overwhelmed the endogenous antioxidant capacity of the animals. However, treatment with P. amarus extract markedly raised intracellular GSH concentration, thereby boosting the biochemical antioxidant pool of the cell. Generally, flavonoids had been reported to increase the concentration of reduced glutathione in the intracellular milleu via an up-regulation of glutamylcysteine synthetase, the rate limiting enzyme in the synthesis of GSH (Moskaug et al., 2005; Myhrstad et al., 2002). P. amarus is rich in flavonoids (Foo, 1993a; Foo and Wong, 1992; Londhe et al., 2008; Wongnawa et al., 2005; Morton, 1981), hence, its ability to boost the antioxidant capacity of experimental animals viz-a-viz GSH synthesis is due to the presence of its flavonoids (Chirdchupunseree and Pramyothin, 2010).

Superoxide dismutase has been suggested as the most vulnerable hepatic antioxidant enzyme in the event of an oxidative attack on the liver (Kharpate et al., 2007). It is the enzyme responsible for the conversion of ROS to H2O2 and eventually to water. Exposure to CCl4 and rifampicin caused a marked depletion in GSH relative to the negative control animals, suggesting toxicity. This marked depletion is traceable to the production of superoxide anion, in excess of the antioxidant capacity of the experimental animals (Mukherjee, 2002). However, treatment with P. amarus extract restored SOD activity to a level comparable with the negative control and silymarin treated animals. This can be attributed to P. amarus-triggered up-regulation in the synthesis of mitochondrial SOD via enhanced transcription of its DNA.

Catalase acts by decomposing H2O2 to water and oxygen thereby preventing its accumulation in the cell. In the present study, exposure to rifampicin and CCl4 resulted in a marked decrease in catalase activity both in the serum and tissue homogenates of albino rats. Depletion in catalase activity as a result of exposure to both toxicants is traceable to a decrease in NADPH or increased lipid peroxidation or both (Arun and Balasubramanian, 2011). However, treatment with P. amarus significantly restored activity of catalase both in the serum and tissue homogenates by increasing the level of NADPH and inhibiting lipid peroxidation as earlier reported (Nazeema and Brindha, 2009).

Administration of CCl4 and rifampicin respectively caused a marked derangement in lipid profile both in the tissue homogenates and serum and of albino rats. Specifically, total cholesterol level was markedly increased relative to negative control. This increment can be attributed to the activation of HMG-CoA reductase, the rate limiting enzyme of cholesterol biosynthesis (Pari et al., 2015). However, when treated with P. amarus, total cholesterol in the liver and kidney as well as serum markedly reduced to a level comparable with animals treated with standard drug. This decrease in cholesterol can be linked to P. amarus triggered increase in HDL-C- which is responsible for the transport of cholesterol to the liver (Der Gaag et al., 2001). On the other hand, administration of CCl4 and rifampicin respectively triggered a marked increase in LDL-C level of experimental rats. Treatment with P. amarus extract attenuated the LDL-C level and reversed it to level comparable with animals treated with the standard drug. The ameliorative effect of P. amarus on the deranged lipid profile can be attributed to the polyphenols and flavonoids in the extract. Flavonoids have been reported to modulate the metabolism of lipid by the inhibiting acyl coenzyme A: cholesterol O-acyltransferase and 3-hydroxy- 3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG CoA) reductase in albino rats (El-Newary et al., 2016; Kurowska et al., 2000). Specifically, quercetin which is abundant in P. amarus extract, has been reported to ameliorate hyperlipidemia, by enhancing lipolysis and upregulation of beta oxidation pathway at the level of gene transcription (Abbass, 2011).

Selected markers of organ toxicity such as urea, uric acid and total bilirubin were significantly raised when animals were exposed to rifampicin and CCl4 relative to the negative control animals. Treatment with P. amarus restored the urea and uric acid levels to levels comparable with the negative control and those treated with silymarin.

Histopathological examination of kidney and liver slices of experimental animals established the medicinal relevance of P. amarus in the management of toxicant-induced hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity. Pramyothin et al. (2007) reported the beneficial role of P. amarus in ethanol-induced model of hepatotoxicity. In line with this finding, treatment with P. amarus histopathological observation of the liver and kidney slices showed a significant restoration of histoarchitecture of the liver and kidney cells.

In conclusion, P. amarus leaf extract curtailed the toxic effects of CCl4 and rifampicin on the liver and kidney respectively. Histopathological examination established the ameliorative potentials of P. amarus leaf extract as reflected in the restoration of both liver and kidney histoarchitecture that were initially distorted by the toxicants. Liver and kidney function biomarkers which were grossly altered following exposure to the toxicants, were also restored dose-dependently in a manner comparable to animals treated with silymarin. Hence, P. amarus has potentials that can be exploited in the management of liver and kidney diseases.

Declarations

Author Contribution statement

T. Ogunmoyole: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

M. Awodooju, S. Idowu and O. Daramola: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge the support of Mr. Oyelade of The Department of Science Laboratory Technology, Federal Polytechnic, Ado Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria.

References

- Abbass A. Efficiency of some antioxidants in reducing cardiometabolic risks in obese rats. J. Am. Sci. 2011;7:1146–1159. [Google Scholar]

- Adeneye A.A., Benebo A.S., Agbaje E.O. Some Protective effect of the aqueous leaf and seed extract of Phyllanthus amarus on alcohol-induced hepatotoxity in rats. West Afr. J. Pharmacol. Drug Res. 2006;229(23):42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Alugoju P., Dinesh B.J., Latha P. Free radicals: properties, sources, targets, and their implication in various diseases. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2015;30(1):11–26. doi: 10.1007/s12291-014-0446-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankur R., Divya K., Seema R., Khan M.U. Phyllanthus amarus: an ample therapeutic potential herb. Int. J. Res. Ayurveda Pharm. 2011;2(4):1096–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Arun K., Balasubramanian U. Comparative Study on Hepatoprotective activity of Phyllanthus amarus and Eclipta prostrate against alcohol induced in albino rats. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2011;2:373–391. [Google Scholar]

- Beutler E.D.O., Kelly B.M. Improved method for the determination of blood glutathione. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1963;61:882–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat K.K.P. Non-Wood Forest Products. Medicinal Plants for Conservation and Health Care. Food and Agriculture Organization; Rome: 2014. Medicinal plant information databases. [Google Scholar]

- Burkill H.M. The useful plants of west tropical Africa. 1994;2 [Google Scholar]

- Calixto J.B. Efficacy, safety, quality control, marketing and regulatory guidelines for herbal medicines (phytotherapeutic agents) Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2000;33(2):179–189. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2000000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier A. second ed. Dorling Kindersley Book; USA: 2000. Encyclopedia of Herbal Medicine: Natural Health; p. 336. [Google Scholar]

- Chirdchupunseree H., Pramyothin P. Protective activity of phyllanthin in ethanol treated primary culture of rat hepatocytes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;128:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S.K., Vasudevan D.M. Effect of lecithin in the treatment of ethanol mediated free radical induced hepatotoxicity. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2006;21:62–69. doi: 10.1007/BF02913068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Der Gaag M., Van T.A., Vermunt S., Scheek L., Schaafsma G., Hendriks H. Alcohol consumption stimulates early steps in reverse cholesterol transport. J. Lipid Res. 2001;42:2077–2083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Newary S.A., Sulieman A.M., El-Attar S.R., Sitohy M.Z. Hypolipidemic and antioxidant activity of the aqueous extract of Cordia dichotoma fruit non-eaten pulp on healthy and hyperlipidemic wistar albino rats. J. Nat. Med. 2016;70(3):539–553. doi: 10.1007/s11418-016-0973-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englehardt A. Measurement of alkaline phosphatase. Aerztl. Lab. 1970;16:42. [Google Scholar]

- Fossati P., Prencipe L., Berti G. Use of 3,5-dichloro-2-hydroxybenzenesulfonic acid/4-aminophenazone chromogenic system in direct enzymic assay of uric acid in serum and urine. Clin. Chem. 1980;26(2):227–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo L.Y. Amarulone, a novel cyclic hydrolyzable tannin from Phyllanthus amarus. Nat. Prod. Lett. 1993;3:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Foo L.Y., Wong H. Phyllanthus iin D, an unusual hydrolysable tannin from Phyllanthus amarus. Phytochem. 1992;31:711–713. [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald W.T., Levy R.I., Fredrickson D.S. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove T.H. Effect of reagent pH on determination of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol by precipitation with sodium phosphotungstate-magnesium. Clin. Chem. 1979;25(4):560–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R.L., Huang Y.L., Ou J.C., Chen C.C., Hsu F.L., Chang C. Screening of 25 compounds isolated from Phyllanthus Species for anti-human hepatitis B virus in vitro. Phytother Res. 2003;17:449–453. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idowu O.A., Soniran O.T., Ajana O., Aworinde D.O. Ethnobotanicalsurvey of anti-malarial plants used in Ogun state, Southwest Nigeria. Afr.J.Pharm. Pharmacol. 2009;4:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Igwe C.U., Nwaogu L.A., Ujuwondu C.O. Assessment of the hepatic effects, phytochemical and proximate compositions of Phyllanthus amarus. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2007;6:728–731. [Google Scholar]

- Kassuya C.A.L., Daniela V.M., Lucilia G.R., Joao B.C. Antiorganic solvents provides a higher efficiency in extracting inflammatory properties of extract, fractions and compounds for antimicrobial activities compared to water lignans isolated from Phyllanthus amarus. Planta Based Med. 2005;71:721–726. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharpate S., Vadnerkar G., Jain D., Jain S. Hepatoprotective activity of the ethanol extract of the leaf of Ptrospermum acerifolium. Indian J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2007;69:850–852. [Google Scholar]

- Kiemer A.K., Hartung T., Huber C., Vollmar A.M. Phyllanthus amarus has antiinflammatory potential by inhibition of iNOS, COX-2, and cytokines via the NF-κB pathway. J. Hepatol. 2003;38:289–297. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00417-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krithika A., Verma R.R.J. Mitigation of carbon tetrachloride induced damage by Phyllanthus amarus in liver of mice. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica – Drug Res. 2009;66:439–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krithika A.R., Verma R.J. Ameliorative potential of Phyllanthus amarus against carbon tetrachloride induced hepatotoxicity. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica – Drug Res. 2009;66:579–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar K.B., Kuttan R. Chemoprotective activity of an extract of Phyllanthus amarus against cyclophosphamide induced toxicity in mice. Phytomedicine. 2005;12:494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurowska E.M., Borradaile N.M., Spence J.D., Carroll K.K. Hypocholesterolemic effects of dietary citrus juices in rabbits. Nutr. Res. 2000;20:121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lodhi P., Tandan N., Singh N., Kumar D., Kumar M. Camellia sinensis (l.) kuntze extract ameliorates chronic ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity in albino rats. J. Evid. Based Compl. Altern. Med. 2014;2014:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2014/787153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londhe J.S., Devasagayam T.P., Foo L.Y., Ghaskadbi S.S. Antioxidant activity of some polyphenol constituents of the medicinal plant Phyllanthus amarus Linn. Redox Rep. 2008;13:199–207. doi: 10.1179/135100008X308984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciel M.A.M., Cunha A., Dantas F.T.N.C., Kaiser C.R. NMR characterization of bioactive lignans from Phyllanthus amarus Schum & Thonn. J. Magn. Reson. Imag. 2007;6:76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder A., Mahato A., Mazumder R. Antimicrobial potentiality of Phyllanthus amarus against drug resistant pathogens. Nat. Prod. 2006;20:323–326. doi: 10.1080/14786410600650404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra H.P., Fridovich I. The role of superoxide anion in the autoxidation of epinephrine and a simple assay for superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 1972;247(15):3170–3175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton J.F. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data. Thomas books; 1981. Atlas of Medicinal Plants of Middle America; p. 1420. [Google Scholar]

- Moskaug J., Carlsen H., Myhrstad M.C., Blomhoff R. Polyphenols and glutathione synthesis regulation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005;81:277S–283S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.277S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee P.K. first ed. Business Horizons Pharmaceutical Publication; New Delhi: 2002. Quality Control of Herbal Drugs; p. 531. [Google Scholar]

- Myhrstad M.C., Carlsen H., Nordstrom O., Blomhoff R., Moskaug J.J. Flavonoids increase the intracellular glutathione level by transactivation of the gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase catalytical subunit promoter. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002;32:386–393. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00812-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazeema T.H., Brindha V. Antihepatotoxic and antioxidant defense potential of Mimosa pudica. Int. J. Drug Discov. 2009;1:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Nikam P.S., Nikam S.V., Sontakke A.V., Khanwelkar C.C. Role of Phyllanthus amarus treatment in Hepatitis-C. Biomed. Res. 2011;22:319–322. [Google Scholar]

- Notka F., Meier G.R., Wagner R. Concerted inhibitory activities of Phyllanthus amarus on HIV replication in vitro and ex vivo. Antivir. Res. 2004;64:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odetola A.A., Akojenu S.M. Antidiarrhoeal and gastro-intestinal potential of the aqueous extract of Phyllanthus amurus (Euphorbiaceae) Afr. J. Med. Sci. 2000;29:119–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbera A.O., Dada O., Adeyeye F., Jewo P.I. Complementary and alternative medicine use in diabetes mellitus. West Afr. J. Med. 2010;29:158–162. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v29i3.68213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa H., Ohishi N., Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Ann. Biochem. 1979;95:351–358. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluwafemi F., Debiri F. Antimicrobial effect of Phyllanthus amarus and Parquetina nigrescens on Salmonella typhi. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2008;11:215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Pari L., Karthikeyan A., Karthika P. Protective effects of hesperidin onoxidative stress dyslipidaemia and histological changes in iron induced hepatic and renal toxicity in rats. Toxicol. Rep. 2015;2:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramyothin P., Ngamtin C., Poungshompoo S., Chaichantipyuth C. Hepatoprotective activity of Phyllanthus amarus Schum & Thonn. extract in ethanol treated rats: in vitro and in vivo studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;114:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajeshkumar N.V., Joy K.L., Kuttan G., Ramsewak R.S., Nair M.G., Kuttan R. Antitumour and anticarcinogenic activity of Phyllanthus amarus extract. J. Ethnoparmacol. 2002;81:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00419-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael K.R., Sabu M.C., Kuttan R. Hypoglycemic effect of methanol extract of Phyllanthus amarus Schum and Thonn on alloxan induced diabetes mellitus in rats and its relation with antioxidant potential. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2002;40:905–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitman S., Franke S. Glutamic – pyruvate transaminase assay by colorimetric method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1957;28:56–60. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/28.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surya S.K., Poornima G., Ravikumar M., Kalaiselvi D., Gomathi V.K. In- vitro antioxidant activity and phytochemical screening of ethanolic extract of Tabernaemontana coronaria (L.) Pharmacol. Online. 2011;2:212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg F., Corrigan D. Taylor & Francis; Abingdon: 2001. Natural Remedies. Their Origins and Uses. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz V., Hänsel R., Tyler V.E. fourth ed. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2001. Rational Phytotherapy. A Physician’s Guide to Herbal Medicine; p. 306. [Google Scholar]

- Singh M., Tiwari N., Shanker K., Verma R.K., Gupta A.K., Gupta M.M. Two new lignans from Phyllanthus amarus. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2009;11:562–568. doi: 10.1080/10286020902939174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha A.K. Colorimetric assay of catalase. Anal. Biochem. 1972;47:389–394. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava V., Singh M., Malasoni R., Shanker K., Verma R.K., Gupta M.M., Gupta A.K., Khanuja S.P.S. Separation and quantification of lignans in Phyllanthus species by a simple chiral densitometric method. J. Separ. Sci. 2008;31:2338. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200700282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyagarajan S.P., Subramanian S., Thirunalasundari T., Venkateswaran P.S., Blumberg B.S. Effect of Phyllanthus amarus on chronic carriers of hepatitis B virus. Lancet. 1988;2:764–766. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tietz N.W. third ed. W.B. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1995. Clinical Guide to Laboratory Tests. [Google Scholar]

- Toyin Y.F., Stephen M., Michael A.F., Udoka E.O. Hepato protective potentials of Phyllanthus amarus against ethanol-induced oxidative stress in rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008;46:2658–2664. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran Q.L., Tezuka Y., Ueda J., Nguyen N.T., Maruyama Y., Begum K. In vitro antiplasmodial activity of antimalarial medicinal plants used in Vietnamese traditional medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003;86:249–252. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinder H. A simple turbidimetric method for the determination of serum cholesterol. Ann. Din. Biochem. 1969;6:165. [Google Scholar]

- Veniamin M.P., Vakirtz C. ChemicaI basis of the carbamidodiacetyl micromethod for estimation of urea, citrulline, and carbamyl derivatives. Clin. Chem. 1970;16(1):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weichselbaum P.E. An accurate and rapid method for the determination of proteins in small amounts of blood serum and plasma. Am. J. Pathol. 1946;16:40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsten S., Cehelyk B. A rapid micro diazo technique for measuring total bilirubin. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1969;25(3):441–446. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(69)90206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongnawa M., Thaina P., Bumrungwong N., Nitiruangjarat A., Muso A., Prasartthong V. Congress on medicinal and aromatic plants: traditional medicine and nutraceuticals. ISHS Acta Hortic. 2005;6:680. III WOCMAP. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav N.P., Pal A., Shanker K., Bawankule D.U., Gupta A.K., Darokarm M.P.S., Khanuja S.P. Synergistic effect of silymarin and standardized extract of Phyllanthus amarus against CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity in Rattus norvegicus. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:1053–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.