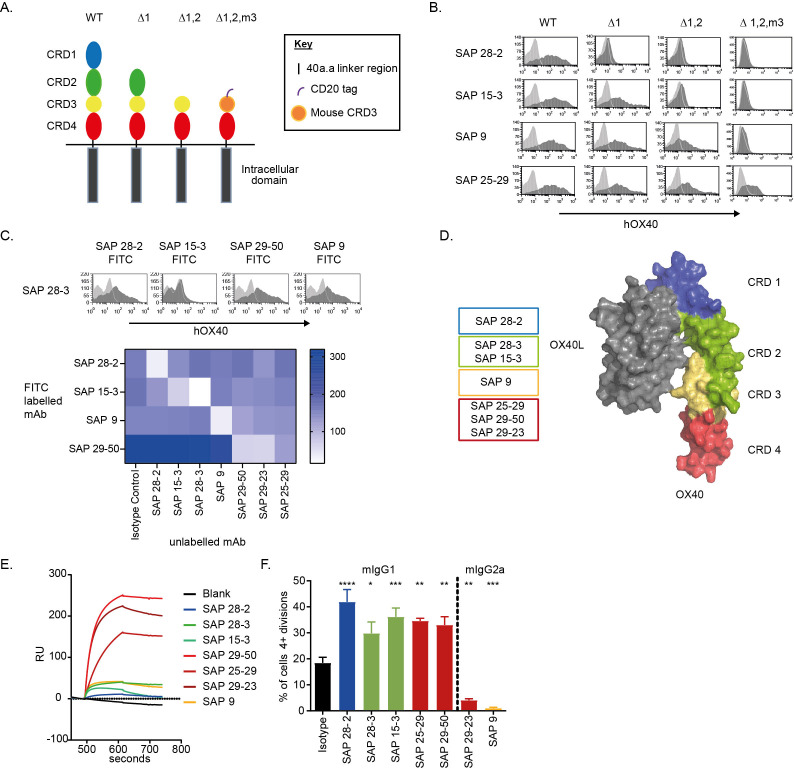

Figure 2.

Characterization of a panel of anti-hOX40 mAb. (A) Schematic of the WT and domain mutant hOX40 constructs generated. CRD3 from mOX40 was used to stabilize the human CRD4 construct. (B) Binding of anti-hOX40 mAb to domain constructs detected by a PE-labeled secondary Fab2 fragments. Representative histograms show hOX40 mAb binding (dark gray histogram) compared with an isotype control (light gray histogram). (C) Representative histograms show anti-hOX40 FITC-labeled mAb binding (dark gray histogram) in relation to an isotype control (light gray histogram) after binding of unlabeled anti-hOX40 mAb. The heat map shows MFI of FITC-labeled antibody binding in the presence of unlabeled antibodies with the absence of color indicating blocking. (D) Diagram summarizing antibody binding domains in relation to the crystal structure of the OX40:OX40L complex. (E) Surface plasmon resonance analysis of anti-hOX40 mAb binding to hOX40-hFc in the presence of hOX40L-His fusion protein. (F) Proliferation of hCD8+ T cells within PBMC cultures in response to sub-optimal anti-CD3 and anti-hOX40 mAb stimulation (representative of four individual donors). Mean±SEM ****p<0.0001, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05, Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. PE, Phycoerythrin; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; CRD, cysteine-rich domain; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; mAb, monoclonal antibody; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; WT, wildtype.