Abstract

Anti‐mitochondrial antibody (AMA)‐positive myositis is an atypical inflammatory myopathy characterized by chronic progressive respiratory muscle weakness, muscular atrophy, and cardiac involvement. Arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, and myocarditis have been reported as cardiac manifestations. Herein, we present the first report of a patient diagnosed with having AMA‐positive myositis with cardiac involvement mimicking cardiac sarcoidosis.

Keywords: Anti‐mitochondrial antibody, Anti‐mitochondrial antibody‐positive myositis, Cardiac sarcoidosis

Introduction

Inflammatory myopathy occurring in association with anti‐mitochondrial antibody (AMA) is rare, but there is a growing recognition for this clinical entity. AMA‐positive myositis is an atypical inflammatory myopathy that is characterized by chronic progressive respiratory muscle weakness, muscular atrophy, and cardiac involvement. 1 Cardiac lesions include arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, and myocarditis. 2 Although varied cardiac manifestations such as regional wall motion abnormality in the left ventricle (LV) without dilation, 3 dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)‐like LV systolic dysfunction, 4 and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC)‐like right ventricular dysfunction have been reported, 5 no typical cardiac findings have been described. Herein, we report the case of a middle‐aged man who was diagnosed as having AMA‐positive myositis associated with cardiac involvement mimicking cardiac sarcoidosis.

Case report

A 55‐year‐old man sought medical attention because of progressive difficulty in getting up from sitting and difficulty in breathing for 2 months. He had a history of weakness in the lower limbs and fatigue for 9 years. He had been evaluated in another centre for the present complaints where an echocardiogram had revealed LV systolic dysfunction. He was then referred to our department and admitted for the management of his worsening symptoms.

The physical examination at admission revealed that he was 158 cm tall and weighed 39 kg. His body mass index (BMI) was 15.6 kg/m2. His breathing was shallow, and he was tachypnoeic. His pulse rate was 64/min, blood pressure was 106/74 mmHg, and transcutaneous oxygen saturation was 98% in room air. Clinical examination revealed no distension of the jugular vein, heart murmur, third heart sound, or pedal oedema. His power on neurological examination of the limb muscles revealed mild weakness in the proximal muscles (manual muscle test score 4), and Gowers' sign was positive.

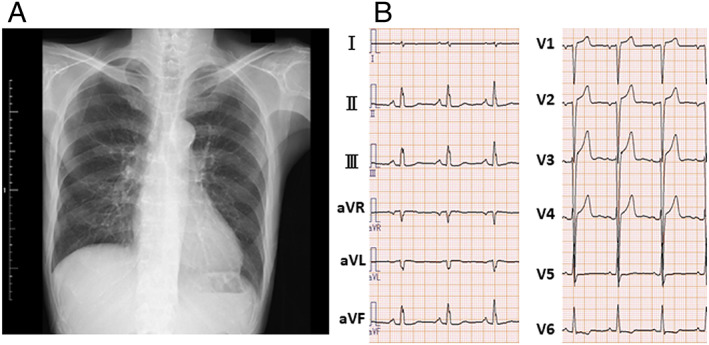

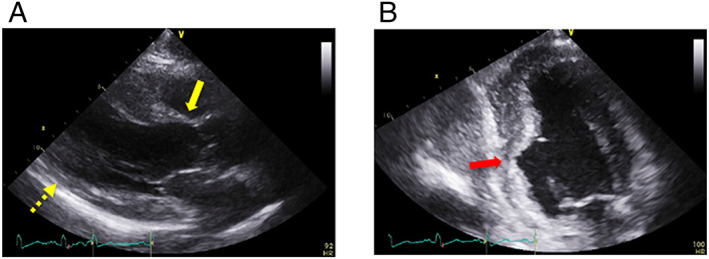

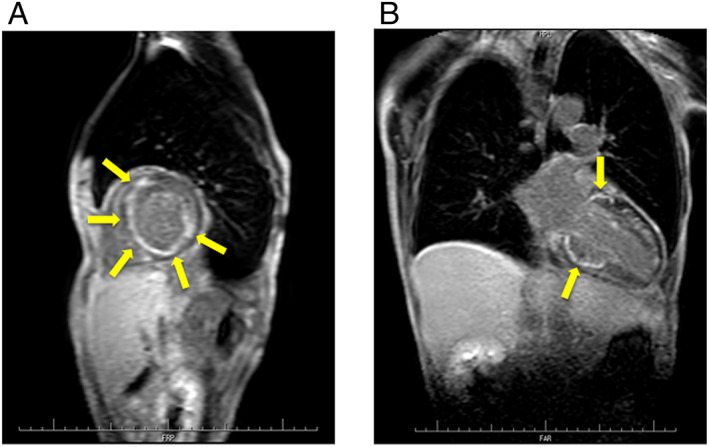

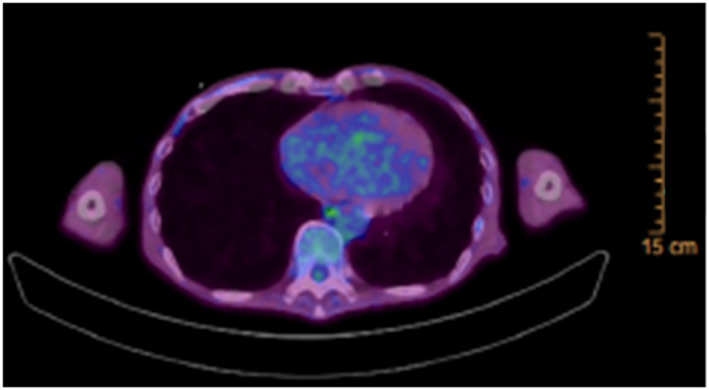

Chest radiography showed no cardiomegaly or lung congestion (Figure 1A). Electrocardiogram showed poor R wave progression and ST segment elevation in the right precordial leads (V1–4) (Figure 1B). The laboratory tests revealed an increased level of serum N‐terminal‐pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (1900 pg/mL) and troponin T (36 ng/L). The serum level of creatine kinase was normal (175 IU/L). The angiotensin‐converting enzyme level was below the normal value (0.6 U/L); and liver function test results including those for bilirubin, transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, and gamma‐glutamyl transpeptidase were normal. The computed tomography of the liver revealed no liver abnormal morphology. Echocardiography showed LV wall thinning in the basal anteroseptum and middle level of inferoseptum walls (Figure 2A, Video S1) and extensive LV asynergies in the interventricular septum and inferior and posterior walls accompanied by an aneurysm from the middle level of the inferoseptal to posterior walls (Figure 2B, Video S2) with decreased LV ejection fraction (EF) (LVEF) (41%). These echocardiographic findings were interpreted as highly suggestive of cardiac sarcoidosis. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) also revealed delayed gadolinium enhancement in the middle layers of the LV portion of the interventricular septum and inferior and posterior walls (Figure 3), which was consistent with the findings of cardiac sarcoidosis. However, subsequent 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) revealed no abnormal FDG uptake in the LV myocardium (Figure 4). The patient had no previous history of advanced atrioventricular block or fatal ventricular arrhythmia. A coronary angiogram showed no stenotic lesions, and the histopathological findings in an endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) specimen obtained from the right side of the interventricular septum showed no evidence of cardiac sarcoidosis, myocardial fibrosis, or secondary cardiomyopathy (Figure 5A, B). Screening of other organs including the lung, eye, and skin showed no evidence of systemic sarcoidosis. Hence, myositis was considered as a possibility because of proximal limb muscle weakness with an impaired 6 min walk test (120 m) and a severe restrictive pattern on pulmonary function tests [vital capacity 1.08 L (30% of predicted values)]. Thus, a neurological consult was obtained. Autoimmune antibodies were measured and positive for anti‐nuclear antibodies (≧1:640), AMA (118.0 index), and rheumatoid factor (27.1 IU/L); and other autoantibodies were negative. Electromyogram examination showed low amplitude in quadriceps muscle and biceps brachii muscle. Nerve conduction study showed no abnormalities. Muscle biopsy of the left biceps brachii demonstrated sporadic necrotic fibres (Figure 6A, B) but no findings of mitochondrial myopathy, dystrophinopathy, and dysferlinopathy.

Figure 1.

(A) The chest radiograph at admission showing no cardiomegaly or lung congestion. (B) The electrocardiogram at admission showing poor R wave progression and ST segment elevation in the right precordial leads (V1–4).

Figure 2.

(A) Parasternal long‐axis echocardiographic view at end‐diastole showing left ventricular wall thinning in the basal anteroseptal (yellow arrow) and mid‐inferoseptal (yellow dotted arrow) walls. (B) Apical two‐chamber echocardiographic view showing an aneurysm from the mid‐inferoseptum to the posterior walls (red arrow).

Figure 3.

(A) Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) in the short‐axis view showing delayed gadolinium enhancement in the middle layers of left ventricular (LV) anteroseptal, inferoseptal, posterior, and lateral walls (yellow arrows). (B) CMR in the long‐axis view showing delayed gadolinium enhancement in the middle layers of LV anteroseptal, inferoseptal, and posterior walls (yellow arrows).

Figure 4.

18F‐Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) showing no abnormal FDG uptake in the left ventricular (LV) myocardium.

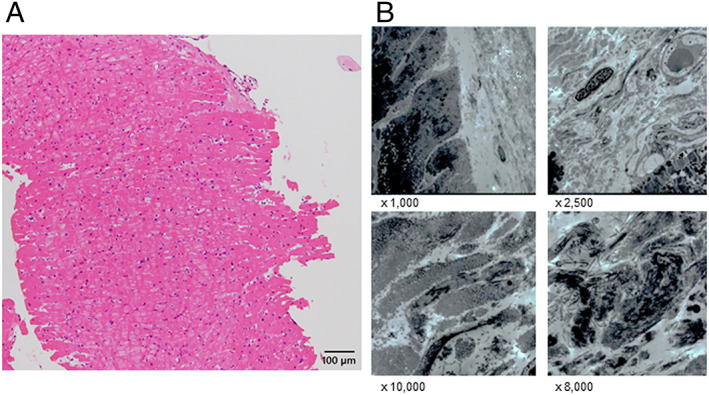

Figure 5.

(A) Histopathological findings showed no evidence of cardiac sarcoidosis, myocardial fibrosis, or findings specific for secondary cardiomyopathy (haematoxylin–eosin stain, ×400, dimensional bar = 100 μm). (B) Electron microscopy showed no findings suggestive of cardiac sarcoidosis or other secondary cardiomyopathy.

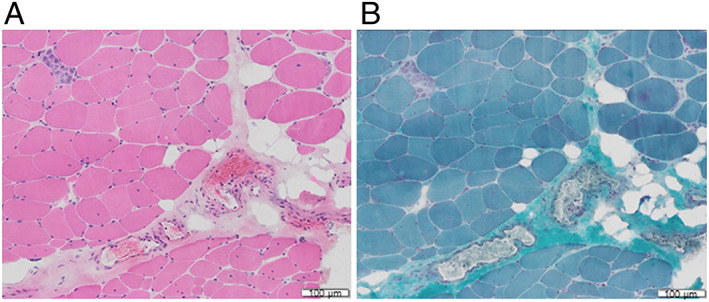

Figure 6.

Muscle biopsy of the left biceps brachii showing fibre size variation, sporadic necrotic fibres, and few inflammatory cell infiltration (A, haematoxylin–eosin stain; B, modified Gomori Trichrome Stain, dimensional bar = 100 μm).

The patient was, therefore, diagnosed as having AMA‐positive myositis; and the LV dysfunction was thought to be caused by cardiac involvement associated with the myositis. Non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) using bilevel positive airway pressure was initiated for respiratory support. After one course of intravenous methylprednisolone, pulse therapy (1 g/day for 3 days) was administered, and high‐dose oral prednisolone therapy (50 mg/day) was started. The dose was subsequently reduced by 10 mg each week to 5 mg/day. Oral cardioprotective drugs, such as enalapril (2.5 mg/day) and bisoprolol (2.5 mg/day), were also administered. Once muscular symptoms and dyspnoea were relieved, NPPV was discontinued. One month after treatment, the 6 min walk test (250 m) and pulmonary function tests [vital capacity 1.50 L (43% of predicted values)] had improved. Follow‐up echocardiogram showed mild recovery in LV systolic function (LVEF: 43%), even though it had not returned to normal. Currently, we are carefully observing the clinical course of the disease in the patient for 3 months.

Discussion

AMA is most commonly found in association with primary biliary cirrhosis 6 ; however, it has also been linked to idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. 1 The frequency of AMA‐positive myositis in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies is reported to vary depending on the country: Japan (11.3–19.5%), France (7.8%), China (5.15%), and North America (0.6%). 1 , 2 , 5 , 6 AMA‐positive myositis is characterized by chronic progressive respiratory muscle weakness, muscular atrophy, and cardiac involvement. 1 Among these patients, 20–30% have cardiac involvement including arrhythmias and LV dysfunction. 1 , 7 Cardiac involvement including a local wall motion abnormality in the LV without dilation and decreased LVEF or DCM‐like or ARVC‐like findings is reported 3 , 4 , 5 ; however, characteristic features have not been elucidated.

In this particular patient, initially, cardiac sarcoidosis was strongly suspected from echocardiographic and CMR findings including LV wall thinning in the basal anteroseptal or mid inferoseptal walls, extensive LV asynergy accompanied by an aneurysm, and delayed gadolinium enhancement in the middle layers of the LV walls. These were consistent with the typical findings of cardiac sarcoidosis. 8 However, in this patient, FDG‐PET revealed no abnormal FDG uptake in the LV myocardium, EMB showed no evidence of cardiac sarcoidosis, and other organs showed no evidence of systemic sarcoidosis. The patient did not match any expert consensus recommendations on the criteria for the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. 8 Based on suspected myositis‐related symptoms such as very low BMI, muscle weakness and a severe restrictive pattern on pulmonary function, myositis was considered. Finally, he was diagnosed as having AMA‐positive myositis on the basis of his neurological symptoms.

In summary, the cause of LV systolic dysfunction in this case was considered to be cardiac involvement associated with AMA‐positive myositis. Intriguingly, the cardiac morphology in this case mimicked cardiac sarcoidosis. However, the influence of immunosuppressive therapy on cardiac involvement with AMA‐positive myositis is unknown. 1 , 2 , 3 In this patient, improvements in muscle symptoms were observed, but no significant improvement in cardiac involvement was observed at 1 month after treatment, which necessitates careful follow‐up of cardiac function.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of cardiac involvement in a patient with AMA‐positive myositis mimicking cardiac sarcoidosis. This was an educational case suggesting that AMA‐positive myositis with cardiac involvement should be considered as a differential diagnosis when muscle symptoms such as respiratory muscle weakness and muscular atrophy are present, even if the cardiac morphology is suggestive of cardiac sarcoidosis.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Supporting information

Video S1. Transthoracic echocardiography in parasternal long‐axis view demonstrates left ventricular wall thinning in the basal anteroseptum and middle level of inferoseptum walls.

Video S2. Transthoracic echocardiography in apical two‐chamber view demonstrates an aneurysm from the mid‐inferoseptum to the posterior walls.

Kadosaka, T. , Tsujinaga, S. , Iwano, H. , Kamiya, K. , Nagai, A. , Mizuguchi, Y. , Motoi, K. , Omote, K. , Nagai, T. , Yabe, I. , and Anzai, T. (2020) Cardiac involvement with anti‐mitochondrial antibody‐positive myositis mimicking cardiac sarcoidosis. ESC Heart Failure, 7: 4315–4319. 10.1002/ehf2.12984.

References

- 1. Maeda MH, Tsuji S, Shimizu J. Inflammatory myopathies associated with anti‐mitochondrial antibodies. Brain 2012; 135: 1767–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Albayda J, Khan A, Casciola‐Rosen L, Corse AM, Paik JJ, Christopher‐Stine L. Inflammatory myopathy associated with anti‐mitochondrial antibodies: a distinct phenotype with cardiac involvement. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018; 47: 552–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bujo S, Amiya E, Kojima T, Yamada S, Maki H, Ishizuka M, Uehara M, Hosoya Y, Hatano M, Kubota A, Toda T, Komuro I. Variable cardiac responses to immunosuppressive therapy in anti‐mitochondrial antibody‐positive myositis. Can J Cardiol. 2019. Nov; 35: 1604 e1609–1604 e1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tanaka K, Sato A, Kasuga K, Kanazawa M, Yanagawa K, Umeda M, Tada M, Tanaka M, Nishizawa M. Chronic myositis with cardiomyopathy and respiratory failure associated with mild form of organ‐specific autoimmune diseases. Clin Rheumatol 2007; 26: 1917–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Uenaka T, Kowa H, Ohtsuka Y, Seki T, Sekiguchi K, Kanda F, Toda T. Less limb muscle involvement in myositis patients with anti‐mitochondrial antibodies. Eur Neurol 2017; 78: 290–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hou Y, Liu M, Luo YB, Sun Y, Shao K, Dai T, Li W, Zhao Y, Yan C. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies with anti‐mitochondrial antibodies: clinical features and treatment outcomes in a Chinese cohort. Neuromuscul Disord 2019; 29: 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koyama M, Yano T, Kikuchi K, Nagahara D, Ishibashi‐Ueda H, Miura T. Lethal heart failure with anti‐mitochondrial antibody: an arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy mimetic. Eur Heart J 2017; 38: 123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Birnie DH, Kandolin R, Nery PB, Kupari M. Cardiac manifestations of sarcoidosis: diagnosis and management. Eur Heart J 2017; 38: 2663–2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video S1. Transthoracic echocardiography in parasternal long‐axis view demonstrates left ventricular wall thinning in the basal anteroseptum and middle level of inferoseptum walls.

Video S2. Transthoracic echocardiography in apical two‐chamber view demonstrates an aneurysm from the mid‐inferoseptum to the posterior walls.