Abstract

Aims

Syncope can lead to injuries. We determined the frequency, severity, and predictors of injuries due to syncope in cohorts of syncope patients.

Methods and results

Participants were enrolled in the POST2 (fludrocortisone) and POST4 (midodrine) vasovagal syncope (VVS) randomized trials, and POST3 enrolled patients with bifascicular block and syncope. Injury was defined as minor (bruising, abrasions), moderate (lacerations), and severe (fractures, burns, joint pain), and recorded up to 1 year after enrolment. A total of 459 patients (median 39 years) were analysed. There were 710 faints occurred in 186 patients during a 1-year follow-up. Fully 56/186 (30%) of patients were injured with syncope (12% of overall group). There were 102 injuries associated with the 710 faints (14%), of which 19% were moderate or severe injuries. Neither patient age, sex, nor the presence of prodromal symptoms associated with injury-free survival. Patients with bifascicular block were more prone to injury (relative risk 1.98, P = 0.018). Patients with ≥4 faints in the prior year had more injuries than those with fewer faints (relative risk 2.97, P < 0.0001), but this was due to more frequent syncope, and not more injuries per faint. In VVS patients, pharmacological therapy significantly reduced the likelihood of an injury due to a syncopal spell (relative risk 0.64, P = 0.015). Injury severity did not associate with age, sex, or prior-year syncope frequency.

Conclusion

Injuries are frequent in syncope patients, but only 4% of injuries were severe. None of age, sex, and prodromal symptoms associate with injury.

Keywords: Syncope, Vasovagal, Injury, Injury severity, Clinical trial

What’s new?

We determined the frequency, severity, and predictors of injuries due to syncope in cohorts of 459 syncope patients in three randomized clinical trials of syncope.

Injuries occurred in 14% of patients.

Eighty-one percent of injuries were only abrasions or contusions.

Neither age nor sex predicted injuries.

Patients with a recent history of more frequent syncope were also more likely to be injured.

Active pharmacologic treatment reduced the risk of injury with each faint.

Introduction

Syncope is a common clinical problem affecting at least 40% of adults in their lifetime, and recurs in at least 13% of adults.1,2 Syncope recurrences affect physical, psychological, and psychosocial aspects of daily life and lead to reduced quality of life.3,4 Vasovagal syncope (VVS) is the most common type of syncope, accounting for about half of syncope presentations to emergency departments.5 Vasovagal syncope does not increase the risk of death for most patients, and many physicians consider it a benign affliction. However, sudden incapacitation can cause injury, and we do not know the likelihood and severity of injuries due to a syncopal spell.

Injury data are available from three Prevention of Syncope Trials (POST), including the POST26 study of fludrocortisone in VVS, the POST47 study of midodrine in VVS, and the POST38 study, which was a pragmatic randomized trial of pacing vs. implantable loop recorders in generally elderly patients with bifascicular block and syncope. All three studies collected detailed information about injuries and their severity with each syncopal spell.

The present study aimed to investigate the frequency, severity, and predictors of injuries due to syncope in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of syncope in the POST2,6 POST3,8 and POST47 studies during a 1-year follow-up. We analysed the predictive effects of demographic and symptom characteristics, as well as the impact of pharmacological therapy on the likelihood of injuries from syncope.

Methods

Study populations

The study population consisted of syncope patients who were enrolled in one of three randomized syncope trials. The POST2 trial6 studied fludrocortisone in VVS (NCT00118482), the POST4 trial7 studied midodrine in VVS (NCT01456481), and the POST3 trial8 was a pragmatic randomized trial of pacing vs. implantable loop recorders in generally elderly patients with bifascicular block and syncope (NCT01423994). POST2 and POST4 included normotensive patients with at least two VVS spells ascertained with the Calgary Syncope Symptom Score. POST3 included patients at least 50 years old with bifascicular block and at least one syncopal spell in the previous year, and no clear diagnosis. All three studies were approved by ethics review committees in all centres. In all three studies, patients were asked to notify the nurse coordinator as soon as possible after a syncopal spell. Syncope incidence and descriptors and details of injuries were captured in prespecified case report forms and open text narratives.

Analytic approach

We described the incidence of injuries on a per-person and per-faint basis, including categorization by severity. Syncope severity was defined as minor (bruising), moderate (abrasions, lacerations), and severe (fracture, burns, head injury, or joint pain). We then tested the association of demographic, symptom, and treatment variables with the likelihood of injury.

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS 21 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for data analysis. Summary descriptions included means and standard deviations, or medians and interquartile intervals where appropriate. Survival analysis used the Kaplan–Meier technique with the statistical significance of differences tested with the Wilcoxon log-rank test. The significance of associations of categorical values were tested with the χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests (conditional on expected counts). The differences between distributions were tested with T-tests.

Results

Study populations

In the three study populations, there were a total of 459 syncope patients [median 39 years old; 278 (61%) female; Table1]. POST2 enrolled 210 patients (mean 34 years; 70% female), with a median syncope frequency of 4 in the year prior to enrolment, and a median duration of follow-up of 7.8 months. POST4 enrolled 134 patients (mean 35 years; 73% female), with a median syncope frequency of 6 in the year prior to enrolment, and a median duration of follow-up of 8.7 months. POST3 enrolled 115 patients (mean 76 years; 30% female), with a median syncope frequency of 2 in the year prior to enrolment, and a median duration of follow-up of 33 months.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and frequency of injuries

| POST 2 | POST 4 | POST 2 and 4 | POST 3 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 210 | 134 | 344 | 115 | 459 |

| Mean age | 34 | 35 | 35 | 76 | 45 |

| Female, n (%) | 146 (70%) | 98 (73%) | 244 (71%) | 34 (30%) | 278 (61%) |

| Syncope in prior year, median | 4 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Median follow-up duration, months | 7.8 | 8.7 | 8.4 | 33.0 | 11.9 |

| Patients fainted, n (%) | 97 (46%) | 68 (51%) | 165 (48%) | 21 (18%) | 186 (41%) |

| Patients injured, n | 29 | 18 | 47 | 9 | 56 |

| Patients injured, % total | 14% | 13% | 14% | 8% | 12% |

| Patients injured, % of fainters | 30% | 26% | 28% | 43% | 30% |

| Total number of faints, n | 453 | 220 | 673 | 37 | 710 |

| Total number of injuries, n | 53 | 39 | 92 | 10 | 102 |

| Injuries per faint, % | 12% | 18% | 14% | 27% | 14% |

| Minor injuries, n (%) | 41 (77%) | 36 (92%) | 77 (84%) | 6 (60%) | 83 (81%) |

| Moderate injuries, n (%) | 10 (19%) | 2 (5%) | 12 (13%) | 3 (30%) | 15 (15%) |

| Severe injuries, n (%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (10%) | 4 (4%) |

Syncope and injuries

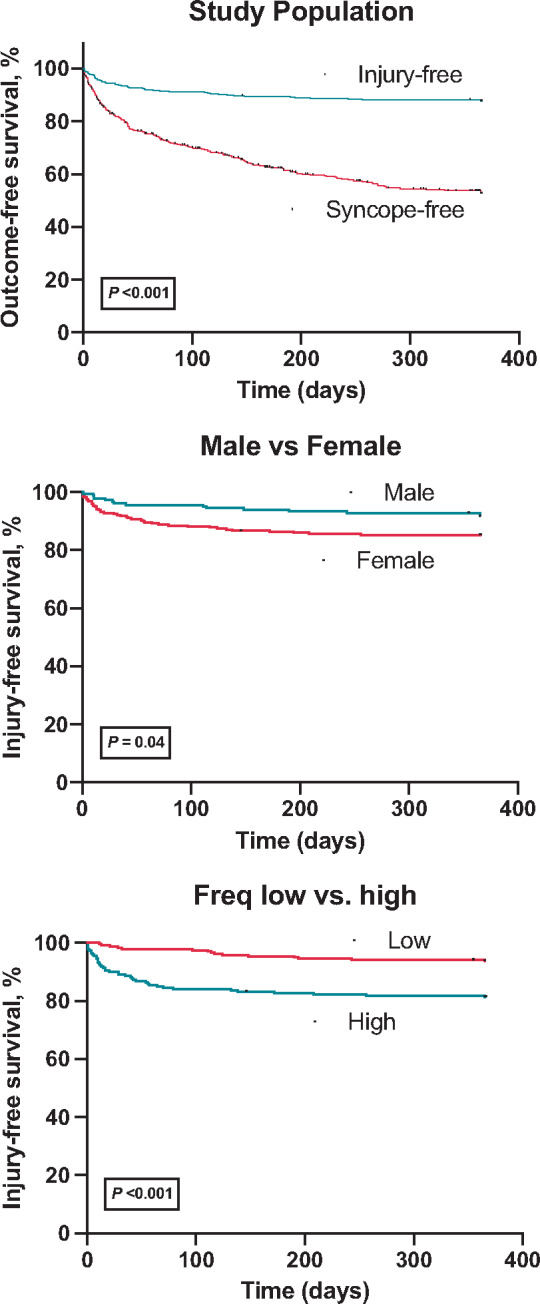

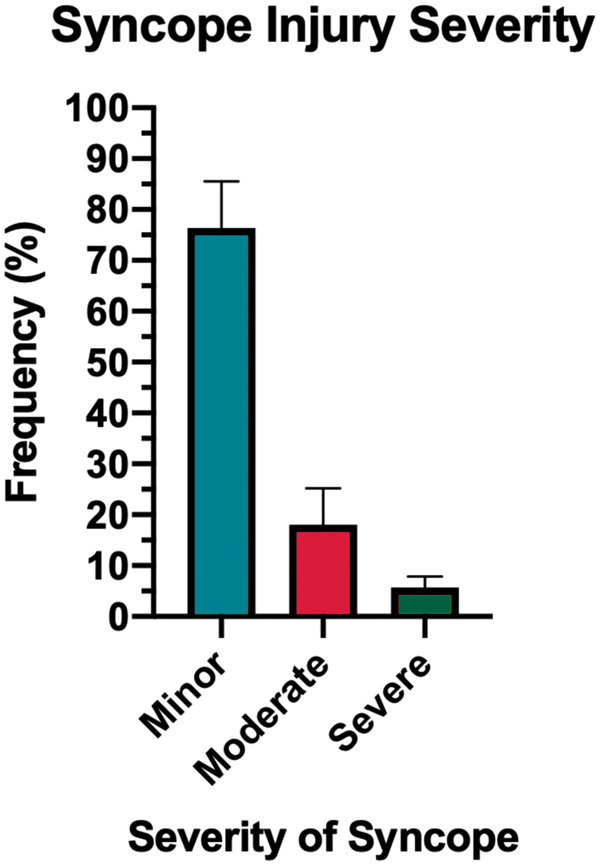

During a 1-year follow-up period, 186 patients had at least one episode of syncope and there was a total of 710 faints (Figure 1, top panel). Of the 186 patients who fainted, 56 (30%) had at least one injury related to syncope (12% of the total study population of 459 patients, Table 2; Figure 1, top panel). In the patients who fainted, none of age, sex, type of population, presence of prodrome, or drug therapy associated with the likelihood of a patient reporting being injured (Table 3). An injury related to syncope occurred in 102 of the 710 (14%) syncopal episodes (Table 4). Of the 102 total injuries, 83 (81%) were minor, 15 (15%) were moderate, and 4 (4%) were severe in nature (Table 1; Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Survival free of events in follow-up. Top panel, comparison of syncope and injury rates in the total population. Middle panel, comparison of survival free of injury in males and females. Bottom panel, comparison of survival free of injury in patients with more or fewer than the median numbers of faints in the year before study enrolment. The median number of faints in the year before randomization was 3.

Table 2.

Risk factors for injury per patients

| Population | Size, n | Injured, n | Mean risk (CI) | Relative risk (CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 459 | 56 | 0.12 (0.10–0.15) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 181 | 15 | 0.08 (0.05–0.13) | ||

| Female | 278 | 41 | 0.15 (0.11–0.19) | 1.78 (1.02–3.12) | 0.044 |

| Age | |||||

| <Median | 214 | 28 | 0.13 (0.09–0.18) | ||

| >Median | 245 | 28 | 0.11 (0.08–0.16) | 0.87 (0.54–1.43) | 0.32 |

| Population type | |||||

| Bifascicular block | 115 | 9 | 0.08 (0.04–0.14) | ||

| Vasovagal | 344 | 47 | 0.14 (0.10–0.18) | 1.59 (0.81–3.14) | 0.089 |

| Prior year, n | |||||

| <Median | 239 | 15 | 0.06 (0.04–0.10) | ||

| >Median | 220 | 41 | 0.19 (0.14–0.24) | 2.97 (1.69–5.21) | <0.0001 |

| Prodrome | |||||

| Absent | 61 | 15 | 0.25 (0.15–0.37) | ||

| Present | 28 | 11 | 0.39 (0.24–0.58) | 1.60 (0.85–3.02) | 0.075 |

| Drug therapy | |||||

| Placebo | 172 | 24 | 0.14 (0.10–0.20) | ||

| Active | 172 | 23 | 0.13 (0.09–0.19) | 0.96 (0.56–1.63) | 0.88 |

The mean age in the total study population was 45 and the median number of faints in the year before randomization was 3. Prodromal symptoms were recorded in POST 3 and 4. The bifascicular heart block population was in POST 3 and the vasovagal population was in POST 2 and 4.

CI, confidence interval.

Table 3.

Risk factors for injury in patients who fainted

| Population | Size, n | Injured, n | Mean risk (CI) | Relative risk (CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 186 | 56 | 0.30 (0.24–0.37) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 55 | 15 | 0.27 (0.15–0.45) | ||

| Female | 131 | 41 | 0.31 (0.22–0.42) | 0.87 (0.53–1.44) | 0.59 |

| Age | |||||

| <Median | 110 | 28 | 0.25 (0.17–0.37) | ||

| >Median | 76 | 28 | 0.37 (0.24–0.53) | 0.69 (0.45–1.10) | 0.10 |

| Population type | |||||

| Bifascicular block | 21 | 9 | 0.43 (0.24–0.63) | ||

| Vasovagal | 165 | 47 | 0.28 (0.22–0.36) | 0.66 (0.38–1.15) | 0.15 |

| Prior year, n | |||||

| <Median | 50 | 15 | 0.30 (0.17–0.50) | ||

| >Median | 136 | 41 | 0.30 (0.22–0.41) | 0.99 (0.61–1.63) | 0.98 |

| Prodrome | |||||

| Absent | 58 | 15 | 0.52 (0.29–0.85) | ||

| Present | 31 | 11 | 0.24 (0.12–0.43) | 0.73 (0.38–1.39) | 0.34 |

| Drug therapy | |||||

| Placebo | 95 | 24 | 0.25 (0.16–0.38) | ||

| Active | 70 | 23 | 0.33 (0.21–0.49) | 0.77 (0.48–1.24) | 0.28 |

The mean age in the total study population was 45 and the median number of faints in the year before randomization was 3. Prodromal symptoms were recorded in POST 3 and 4. The bifascicular heart block population was in POST 3 and the vasovagal population was in POST 2 and 4.

CI, confidence interval.

Table 4.

Risk factors for injury per faint

| Population | Size, n | Injuries, n | Mean risk (CI) | Relative risk (CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 710 | 102 | 0.14 (0.12–0.17) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 154 | 23 | 0.15 (0.10–0.21) | 1.05 (0.68–1.61) | 0.82 |

| Female | 556 | 79 | 0.14 (0.12–0.17) | ||

| Age | |||||

| <Median | 346 | 51 | 0.15 (0.11–0.19) | 1.05 (0.74–1.51) | 0.39 |

| >Median | 364 | 51 | 0.14 (0.11–0.18) | ||

| Population type | |||||

| Bifascicular block | 37 | 10 | 0.27 (0.15–0.43) | 1.98 (1.13–3.47) | 0.018 |

| Vasovagal | 673 | 92 | 0.14 (0.11–0.17) | ||

| Prior year, n | |||||

| <Median | 74 | 16 | 0.22 (0.14–0.32) | 1.60 (0.99–2.57) | 0.027 |

| >Median | 636 | 86 | 0.14 (0.11–0.16) | ||

| Prodrome | |||||

| Absent | 116 | 29 | 0.25 (0.18–0.34) | 1.60 (0.91–2.81) | 0.10 |

| Present | 96 | 15 | 0.16 (0.10–0.24) | ||

| Drug therapy | |||||

| Placebo | 360 | 59 | 0.16 (0.13–0.21) | ||

| Active | 313 | 33 | 0.11 (0.08–0.15) | 0.64 (0.43–0.96) | 0.015 |

| Device therapy | |||||

| ILR | 11 | 5 | 0.40 (1.1–10.2) | ||

| Pacemaker | 10 | 4 | 0.45 (1.6–11.7) | 1.1 (0.42–3.1) | 0.8 |

Size, n is the number of faints. Injured, n is the number of faints resulting in an injury. The mean age in the total study population was 45 and the median number of faints in the year before randomization was 3. Prodromal symptoms were recorded in POST 3 and 4. The bifascicular heart block population was in POST 3 and the vasovagal population was in POST 2 and 4.

CI, confidence interval; ILR, implantable loop recorder.

Figure 2.

Distribution of minor, moderate, and severe injuries associated with syncopal spells.

Injury in each study

Of the 115 patients with bifascicular block (POST3), 21 (18%) fainted at least once over the first 12 months of follow-up, and 10 (8%) reported at least one injury related to syncope (Table 1). Over the first 12 months, there were 37 faints, of which 10 (27%) resulted in injury (Table 1). Of the 344 patients with VVS (POST2 and POST4), 165 (48%) fainted at least once during follow-up, and 47 (14%) reported at least one injury due to syncope. Over the 12 months, there were 673 faints in VVS patients, of which 92 (14%) resulted in injury.

More patients with VVS had a syncope recurrence during 12 months follow-up than patients with bifascicular block (48% vs. 18%; P < 0.0001). Patients with VVS who fainted did not have a significantly different risk of injury due to syncope during 12 months follow-up than patients with bifascicular block (Table3, 28% vs. 43%; relative risk 0.66, P = 0.15). In contrast, patients with bifascicular block had a significantly higher risk of injury per faint than VVS patients (Table4, 27% vs. 14%; relative risk 1.98, P = 0.018). Of the 344 patients with VVS (POST2 and POST4), 165 (48%) fainted at least once during follow-up, and 47 (14%) reported at least one injury due to syncope. Over the 12 months, there were 673 faints in VVS patients, of which 92 (14%) resulted in injury.

Patients with VVS had a numerically higher risk of injury due to syncope during 12 months follow-up than patients with bifascicular block (Table2, 14% vs. 8%; relative risk 1.59, P = 0.089). In contrast, patients with bifascicular block had a significantly higher risk of injury per faint than VVS patients (Table4, 27% vs. 14%; relative risk 1.98, P = 0.018). In other words, the bifascicular block patients were more likely to be injured if they fainted.

Predictors of injury severity

When injury severity was analysed by minor vs. moderate/severe, none of age (P = 0.4), sex (P = 0.6), or prior-year syncope frequency (P = 0.9) predicted injury severity. Syncope patients with bifascicular block had a trend towards a greater proportion of moderate or severe injuries than VVS patients (40% vs. 16%, P = 0.087; Table 1).

Demographics and syncope-related injury

Females with syncope were more likely to be injured, having a lower injury-free survival at 1 year than males (65% vs. 85%; P = 0.03; Figure 1, middle panel). They were also more likely to faint (females 527 faints/278 fainters; males 183 faints/181 fainters). Similarly, a significantly higher proportion of females than males were injured due to syncope (15% vs. 8%, relative risk 1.78, P = 0.044; Table 2). Females who fainted reported a similar risk of injury per patient as did men (Table3, 31% vs. 27%, P = 0.59). However, the risk of injuries per faint in males and females were similar (15% vs. 14%, relative risk = 1.05, P = 0.82, Table 4). Populations older and younger than the median age had similar proportions of patients injured due to syncope (13% vs. 11%, P = 0.32; Table 2) and similar likelihoods of injuries per faint (15% vs. 14%, P = 0.39; Table 4).

Prior-year syncope and syncope-related injury

The number of faints in the year before study enrolment predicted more likely injury in the follow-up period. At least 38% of patients with four or more faints in the prior year were injured during syncope compared to only 24% of those with fewer than four faints in the prior year (P = 0.03; Figure 1, bottom panel). Similarly, Table 2 reports that patients with more than the median number of faints in the prior year were more likely to be injured (19% vs. 6%, relative risk 2.97, P < 0.0001; Table 2).

In contrast, the proportion of injuries per faint was significantly higher in patients with less frequent syncope in the prior year (22% vs. 14%, relative risk 1.60, P = 0.0027; Table 4). That is, patients with more frequent syncope were more likely to be injured, and less likely to be injured per faint. The higher likelihood of injury was due to the higher likelihood of syncope, and not a higher risk of injury per faint.

Prodromes

The presence of prodromal symptoms was recorded only from patients enrolled in POST3 and POST4. Of the 89 patients who fainted during the 12-month observation period, 61 (69%) patients had prodrome symptoms, and 28 (31%) did not have prodromal symptoms. There was a trend towards a lower proportion of syncope patients with prodromal symptoms having an injury than those without prodromal symptoms (39% vs. 24%; relative risk 1.60, P = 0.075; Table 2). As well, the likelihood of injury per faint in patients with and without prodromal symptoms were similar 25% and 16% (relative risk 1.60, P = 0.10; Table 4).

Drug treatment and injury

Among VVS patients enrolled in the POST2 and POST4 studies, patients assigned to treatment with either fludrocortisone or midodrine had a significantly lower likelihood of injury per syncopal episode that those in the placebo group (Table 4). The relative risk of injury per faint for patients on active treatment compared to placebo was 0.64 (95% confidence interval 0.43–0.96, P = 0.015). In the bifascicular population, there was no evidence that pacemakers reduce the risk of injury compared to permanent pacemakers.

National perspectives

To estimate rates of severe injury without syncope we compared fall-related injuries leading to hospital admissions in four national datasets (Table 5) with the data from POST 2–4. Serious injuries were generally defined as fractures or head trauma, which is similar to our definition. In Denmark,9 Canada,10 the UK,11 and the USA, the12 proportions of the populations admitted with fall-related injuries were 3.2%, 0.4%, 0.33%, and 0.24%, respectively. In POST 2–4, the risk of serious injury was 4/459, or 0.9%.

Table 5.

Rates of admissions for serious fall-related injury in Denmark, the USA, the UK, and Canada

| Population | Data type | Inclusion | Period 2 | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Danish national | Administrative | No recent syncope | One-year admission due to fall-related injury | 3.2 |

| US national | Administrative | Injury admission | One-year admission due to fall-related injury | 0.24 |

| UK national | Administrative | Injury admission | One-year admission due to fall-related injury | 0.33 |

| Canadian national | Administrative | Injury admission | One-year admission due to fall-related injury | 0.4 |

| All study patients | POST 2–4 | Recent syncope | One-year syncope-related serious injury | 0.9 |

These populations serve as controls for the likelihood of serious injury not related to syncope.

Discussion

Using prospectively collected data from three randomized trials, we estimated the likelihood of injuries during syncope. Overall, there is a 14% risk of injury per faint, and almost one-fifth of these are moderate or severe in nature. Fully 30% of patients who faint are injured in a 1-year observation period. The risk of injury is higher in patients with more frequent syncope. Modestly effective drug therapy significantly reduces the risk of injury in VVS patients.

Syncope is very common, and often assumed to be troublesome but not particularly dangerous.1 There is a significant psychosocial impact on quality of life, which is reduced substantially in patients with recurrent syncope.3,13,14 In particular, Ng et al.3 reported in patients with VVS that the most severely reduced of eight dimensions of quality of life was physical role functioning. Patients feel limited in their physical roles and are significantly more anxious than matched subjects who do not faint. The results reported here substantiate these apprehensions and anxiety: the risk of injury is significant with each faint, and some of these injuries are moderate to severe in severity. The risk of injury per faint in the total study population was 14%, with patients having bifascicular block at significantly higher risk than those with VVS. In this population, followed for no more than 1 year, the risk of injury per person was 12%, with similar groups at higher risk. Fortunately, the large majority of injuries (81%) are no worse than abrasions and contusions, and the likelihood of severe injuries per faint is only 4%.

Injuries due to syncope have been reported by others, although usually in cross-sectional surveys.15–17 Bartoletti et al.18 reported the prevalence of injuries related to syncope at the time of presentation at the emergency room. There was an incidence of 29% of traumatic injuries for all syncope causes, and 24% for VVS. Ammirati et al.15 recorded detailed histories of 346 patients with at least two recent spells of VVS. Fully 27% had been injured at least once, and 9% were admitted to hospital because of the degree of injury. Factors that predicted injury included male sex, more frequent syncope, and a shorter prodromal period. One strength of the results reported here is that the data were collected prospectively and over a reporting period up to a year, rather than at a single timepoint in the patients’ lives.

Our results complement those of Aydin et al.,17 who followed 316 patients with syncope after an initial assessment. The mean age was 50 years and they had had a median of 3 syncopal spells in about 1 year before assessment. Only 40% had positive tilt tests. All received diagnostic explanation, reassurance, and dietary and counterpressure manoeuvre education, as did our patients. In a 2-year telephone and mail follow-up only 27% of patients reported a syncope recurrence. Injuries occurred in 17/87 patients with syncope (20%) and 17/316 patients who completed follow-up (5.4%). In contrast, our patients had a higher reported likelihood of both syncope and injuries. Possible contributing factors include a higher risk population in clinical trials, unreported differences in confounding factors, and much more intense follow-up and reporting in clinical trials. As well, Aydin et al.17 focused on the effect of conservative treatment, while our analysis aimed to determine risk factors for both injuries per person and importantly injuries per faint.

To estimate rates of severe injury without syncope we compared fall-related injuries leading to hospital admissions in four national datasets (Table 5) with the data from POST 2–4. There is no control group without syncope and we cannot determine directly whether syncope increases the overall risk of fall-related injury.9 These are structurally similar controls in that they report the admission rates for injuries for all subjects, rather than based on a syncope-related injury. Assuming that many fall-related severe injuries would be hospitalized these provide an estimate of their incidence. The apparent differences between Danish9 and USA,12 UK,11 Canadian10 estimates may be due to differences in populations, inclusion criteria, active study enrolment compared to passive administrative datasets, and analytic methodologies.

Females are at higher risk of fainting and of injury due to fainting, both per person and per faint. However, their risk of injury per faint was similar to that of males, suggesting that this effect was simply due to females fainting more frequently in follow-up. Age was not a factor, as older and younger patients had similar risks of injury.

The significantly worse outcome of syncope patients with bifascicular block does raise concerns. These patients had both an increased risk of injury per faint and an increased risk of moderate and severe injury. This does not seem to be a simple matter of increased age. We conjecture this may be due to the presence of multiple co-morbidities and risk factors, including possibly osteoporosis,19 lack of mobility,20 and frailty21 in this older cohort. Age by itself did not predict injury, but women with bifascicular block appear to be at particularly elevated risk of injury. Given the impact of fractures on the elderly, it may be that aggressive early intervention is warranted, and a formal geriatrics consultation might be helpful. Working with a Falls clinic may also be helpful.

Limitations

Participants included in this analysis were all enrolled in clinical trials, which means that they were highly selected and self-selected, which might limit the generalizability of the results. Possibly this overestimated the likelihood of being injured with each faint, although we did not detect this effect. Only patients with recurrent syncope are included in this series and not solely patients with the first episode. As well, the proportion of patients who were injured is similar to that reported by Aydin et al.,17 using a related but lower risk study population. There is no control group without syncope and we cannot determine directly whether syncope increases the overall risk of fall-related injury.9 We did not collect uniform information on co-morbidities (POST2 and POST4 anticipated a predominantly young and healthy population) or about prodromal symptoms (not collected in POST2). The population of POST 3 is quite different from that of POST2 and 4, and care should be taken when combining the data. To ameliorate this we also examined bifascicular block as a separate risk factor. The patients in POST3 were about 40 years older than those in POST2 and 4 yet constitute only 25% of the study population. This relatively small sample size of older patients may have prevented us from detecting serious injuries such as hip fractures. These can lead to serious morbidities and occasionally mortality. Even when considered in aggregate, this study’s sample size was too small to ask more detailed and specific questions, such as about the interactions of medication and prodromes and risk factors that predict severe injury. Since the majority of patients with a known diagnosis of syncope do not seek medical attention, the unselected population rate of injuries due to syncope is unknown.

Conclusion

The frequency of injuries is significant in patients with syncope, including VVS, although most are simply contusions and abrasions. Patients with conduction disease appear to be a higher risk group requiring particular care. Patients and physicians should be alert to the consequences of recurrent syncope and injuries, and that females and patients with frequent syncope are more likely to be injured. Finally, patients with syncope should be assessed for other factors that increase the risk of moderate to severe trauma including comorbidities, frailty, specific occupational risk, and sports activities.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the Cardiac Arrhythmia Network of Canada, a Canadian federal Networks of Centres of Excellence. The data are from the Prevention of Syncope Trials 2, 3, and 4, which were funded by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Conflict of interest: No authors have any relevant financial activities outside the submitted work or any other relationships or activities that readers could perceive to have influenced, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing what is written.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Shen W-K, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, Cohen MI, Forman DE, Goldberger ZD. et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:e39–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ruwald MH, Hansen ML, Lamberts M, Hansen CM, Numé AK, Vinther M. et al. Comparison of incidence, predictors, and the impact of co-morbidity and polypharmacy on the risk of recurrent syncope in patients <85 versus ≥85 years of age. Am J Cardiol 2013;112:1610–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ng J, Sheldon RS, Ritchie D, Raj V, Raj SR.. Reduced quality of life and greater psychological distress in vasovagal syncope patients compared to healthy individuals. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018;42:180–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barón-Esquivias G, Gómez S, Aguilera A, Campos A, Romero N, Cayuela A. et al. Short-term evolution of vasovagal syncope: influence on the quality of life. Int J Cardiol 2005;102:315–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blanc J-J, L’Her C, Touiza A, Garo B, L’Her E, Mansourati J.. Prospective evaluation and outcome of patients admitted for syncope over a 1 year period. Eur Heart J 2002;23:815–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sheldon R, Raj SR, Rose MS, Morillo CA, Krahn AD, Medina E. et al. Fludrocortisone for the prevention of vasovagal syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Raj SR, Faris PD, McRae M, Sheldon RS.. Rationale for the prevention of syncope trial IV: assessment of midodrine. Clin Auton Res 2012;22:275–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krahn AD, Morillo CA, Kus T, Manns B, Rose S, Brignole M. et al. Empiric pacemaker compared with a monitoring strategy in patients with syncope and bifascicular conduction block-rationale and design of the Syncope: pacing or Recording in ThE Later Years (SPRITELY) study. Europace 2012;14:1044–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Numé A-K, Carlson N, Gerds TA, Holm E, Pallisgaard J, Søndergaard KB. et al. Risk of post-discharge fall-related injuries among adult patients with syncope: a nationwide cohort study. PLoS One 2018;13:e0206936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slips, trips and falls: Our newest data reveals causes of injury hospitalizations and ER visits in Canada | CIHI. https://www.cihi.ca/en/slips-trips-and-falls-our-newest-data-reveals-causes-of-injury-hospitalizations-and-er-visits-in (June 2020, date last accessed).

- 11.Falls: applying All Our Health - GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/falls-applying-all-our-health/falls-applying-all-our-health (December 2020, date last accessed).

- 12.WISQARS (Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System)|Injury Center|CDC [Internet]. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/ (December 2020, date last accessed).

- 13. Ng J, Sheldon RS, Maxey C, Ritchie D, Raj V, Exner DV. et al. Quality of life improves in vasovagal syncope patients after clinical trial enrollment regardless of fainting in follow-up. Auton Neurosci Basic Clin 2019;219:42–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grimaldi Capitello T, Fiorilli C, Placidi S, Vallone R, Drago F, Gentile S.. What factors influence parents’ perception of the quality of life of children and adolescents with neurocardiogenic syncope? Health Qual Life Outcomes 2016;14:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ammirati F, Colivicchi F, Velardi A, Santini M.. Prevalence and correlates of syncope-related traumatic injuries in tilt-induced vasovagal syncope. Ital Heart J 2001;2:38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sheldon R, Connolly S, Rose S, Klingenheben T, Krahn A, Morillo C. et al. Prevention of syncope trial (POST). Circulation 2006;113:1164–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aydin MA, Mortensen K, Salukhe TV, Wilke I, Ortak M, Drewitz I. et al. A standardized education protocol significantly reduces traumatic injuries and syncope recurrence: an observational study in 316 patients with vasovagal syncope. Europace 2012;14:410–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bartoletti A, Fabiani P, Bagnoli L, Cappelletti C, Cappellini M, Nappini G. et al. Physical injuries caused by a transient loss of consciousness: main clinical characteristics of patients and diagnostic contribution of carotid sinus massage. Eur Heart J 2008;29:618–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keramidaki K, Tsagari A, Hiona M, Risvas G.. Osteosarcopenic obesity, the coexistence of osteoporosis, sarcopenia and obesity and consequences in the quality of life in older adults ≥65 years-old in Greece. J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls 2019;4:91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cao J, Wang T, Li Z, Liu G, Liu Y, Zhu C. et al. Factors associated with death in bedridden patients in China: a longitudinal study. PLoS One 2020;15:e0228423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Viljanen A, Salminen M, Irjala K, Korhonen P, Wuorela M, Isoaho R. et al. Frailty, walking ability and self-rated health in prediting institutionalization: an 18-year follow-up study among Finnish community-dwelling older people. Aging Clin Exp Res 2020; doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01551-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.