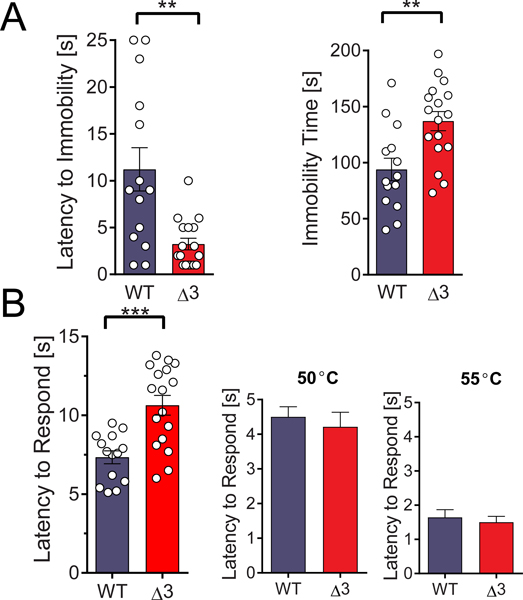

Figure 7. SNAP25Δ3 mutant mice showed altered affect and supraspinal nociception.

A. SNAP25Δ3 animals show greater immobility in the forced swim paradigm. Left panel: Bar graph shows the time spent immobile subsequent to immersion for 16–17-week old littermate male WT or SNAP25Δ3 homozygotes. Immobility time was significantly greater for SNAP25Δ3 than WT littermates (**p< 0.01, Student’s two-tailed t-test) Right panel: Bar graph showing the latency to immobility subsequent to immersion for littermate male WT or SNAP25Δ3 homozygotes in the forced swim paradigm. Latency time before immobility was significantly lower for SNAP25Δ3 than WT littermates (**p< 0.01). B. SNAP25Δ3 animals have impaired nociception. Left panel: Bar graph showing latency required for 20 week old littermate male WT or SNAP25Δ3 homozygotes to respond to supraspinal thermal pain in the hot plate paradigm, in which animals are placed on a plate heated to 55°C and the time required to produce a paw movement is measured. Latency time was significantly greater for SNAP25Δ3 than WT littermates (**p< 0.01, Student’s two-tailed t-test). Right panel: Bar graph showing latency required for 21-week old littermate male WT or SNAP25Δ3 homozygotes to respond to spinal thermal nociception in in the tail flick paradigm, in which mouse tails are immersed in a hot water bath heated to 50° or 55° C and the time required for tail movement is recorded. No differences were detected between littermate SNAP25Δ3 and WT (p= 0.29 and 0.53 respectively, Student’s two-tailed t-test). For A and B, 14 WT mice and 17 SNAP25Δ3 homozygotes were used.