Abstract

Aliarcobacter butzleri is an emerging foodborne and zoonotic pathogen that is usually transmitted via contaminated food or water. A. butzleri is not only the most prevalent Aliarcobacter species, it is also closely related to thermophilic Campylobacter, which have shown increasing resistance in recent years. Therefore, it is important to assess its resistance and virulence profiles. In this study, 45 Aliarcobacter butzleri strains from water poultry farms in Thuringia, Germany, were subjected to an antimicrobial susceptibility test using the gradient strip diffusion method and whole-genome sequencing. In the phylogenetic analysis, the genomes of the German strains showed high genetic diversity. Thirty-three isolates formed 11 subgroups containing two to six strains. The antimicrobial susceptibility testing showed that 32 strains were resistant to erythromycin, 26 to doxycycline, and 20 to tetracycline, respectively. Only two strains were resistant to ciprofloxacin, while 39 strains were resistant to streptomycin. The in silico prediction of the antimicrobial resistance profiles identified a large repertoire of potential resistance mechanisms. A strong correlation between a gyrA point mutation (Thr-85-Ile) and ciprofloxacin resistance was found in 11 strains. A partial correlation was observed between the presence of the bla3 gene and ampicillin resistance. In silico virulence profiling revealed a broad spectrum of putative virulence factors, including a complete lipid A cluster in all studied genomes.

Keywords: Aliarcobacter, emerging pathogen, heavy metal resistance, virulence, antimicrobial resistance, whole-genome sequencing, antibiotic susceptibility

Introduction

The species Aliarcobacter (A.) butzleri (former Arcobacter butzleri) belongs to the genus Aliarcobacter, a member of the Campylobacteraceae family, together with A. cryaerophilus, A. skirrowii, A. thereius, A. cibarius, A. lanthieri, A. faecis, and A. trophiarum (Pérez-Cataluña et al., 2018a,b, 2019).

A. butzleri is an emerging foodborne and zoonotic pathogen that has been considered as a serious hazard to human health (ICMSF, 2002; Collado and Figueras, 2011; Ramees et al., 2017). In humans, A. butzleri infections are associated with self-limiting enteritis, diarrhea and rarely bacteremia; in animals, it has been associated with abortions, mastitis, and gastrointestinal diseases (Logan et al., 1982; Vandamme et al., 1992; Woo et al., 2001; Lau et al., 2002; Vandenberg et al., 2004; Collado and Figueras, 2011; Chieffi et al., 2020).

A. butzleri is the most prevalent foodborne Aliarcobacter species, followed in frequency by A. cryaerophilus and A. skirrowii (Lehner et al., 2005; Collado and Figueras, 2011; Ramees et al., 2017; Caruso et al., 2020). The bacteria have been found in water, vegetables, meat (especially poultry), milk, dairy products, and shellfish (Ho et al., 2006; Hausdorf et al., 2013; Yesilmen et al., 2014; Ramees et al., 2017; Fanelli et al., 2019; Caruso et al., 2020; Chieffi et al., 2020). Since A. butzleri is frequently isolated from food-producing animals, these animals should be considered as an important reservoir (Rahimi, 2014; Giacometti et al., 2015; Rathlavath et al., 2017; Sekhar et al., 2017; Caruso et al., 2018; Chieffi et al., 2020). However, this would require successful colonization of the intestines and contamination during the slaughter process (Chieffi et al., 2020).

The consumption of contaminated food/feed or water is the main transmission route for humans and animals. The contamination of food products is probably a consequence of unhygienic procedures (Chieffi et al., 2020). Contact from person-to-person and companion animals-to-person are also possible ways of transmission to humans (Fera et al., 2009; Collado and Figueras, 2011; Shah et al., 2012a; Giacometti et al., 2015; Ferreira et al., 2016; Ramees et al., 2017; Chieffi et al., 2020).

The antimicrobial susceptibility of A. butzleri has been frequently investigated phenotypically (Harrass et al., 1998; Fera et al., 2003; Houf et al., 2004; Ho et al., 2006; Vandenberg et al., 2006; Abay et al., 2012; Ferreira et al., 2013, 2017; Shah et al., 2013; Rahimi, 2014; Shirzad Aski et al., 2016; Van den Abeele et al., 2016; Pérez-Cataluña et al., 2017; Vicente-Martins et al., 2018; Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020; Parisi et al., 2019). The underlying genetic resistance mechanisms have been studied in more detail in recent years but data is still limited (Abdelbaqi et al., 2007; Merga et al., 2013a; Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020; Parisi et al., 2019; Isidro et al., 2020). In addition to virulence-associated genes that are homologs of genes previously found in Campylobacter (C.) jejuni (pldA, mviN, irgA, iroE, ciaB, hecA, hecB, cj1345, cadF, tlyA), further potential virulence-associated genes have been discovered (Miller et al., 2007; Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020; Isidro et al., 2020). Only little is known about the resistance of A. butzleri to heavy metals (Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020).

Here, we report antibiotic susceptibility profiles of 45 A. butzleri strains isolated from water poultry in Thuringia, Germany, and present insights into their phylogeny. Furthermore, we have complemented these data with 30 A. butzleri genomes from public databases, and described the presence of putative antimicrobial resistance genes, potential heavy metal resistance genes and virulence-associated genes in all genomes.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Culturing, and Identification

In 2016 and 2017, 188 fecal samples were collected from clinically healthy animals from seven water poultry farms in Thuringia, Germany. In detail, 88 fecal samples were collected in 2016 from five water poultry farms from 60 geese (Anser anser), 13 Muscovy ducks (Cairina moschata), and 15 mulard ducks (Cairina moschata × Anas platyrhynchos domesticus). In 2017, 100 fecal samples were gathered from 50 geese, 25 Muscovy ducks, 15 mulard ducks, and 10 Pekin ducks (Anas platyrhynchos domesticus) from seven water poultry farms. A veterinarian collected the fecal samples with the permission of the animal owners.

For this study, no ethical review process was required as there were no experiments with animals as defined by the German Animal Protection Law (Tierschutzgesetz) and the Animal Welfare Laboratory Animal Regulation (Tierschutz-Versuchstierverordnung).

Culturing and identification was performed as described previously (Müller et al., 2020a). Briefly, the Aliarcobacter isolates were cultivated in Arcobacter broth (Oxoid GmbH, Wesel, Germany), and then spread on plates (Mueller-Hinton-agar/5% defibrinated bovine blood; Sifin GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Nutrient broth and agar plates were supplemented with antibiotics (cefoperazone, amphotericin, and teicoplanin (CAT), SR0174, Oxoid GmbH). The incubation criteria were: 48–72 h at 30°C in microaerophilic atmosphere (5% O2, 10% CO2, and 85% N2). Suspicious colonies were further cultivated and subsequently identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) as described before (El-Ashker et al., 2015; Hänel et al., 2018). DNA was purified using the High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions and confirmation of the species identification was done with a multiplex PCR assay (Houf et al., 2000).

Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

Antibiotic susceptibility was determined using the gradient strip diffusion method (E-TestTM, bioMérieux, Nürtingen, Germany) as previously described (Müller et al., 2020a). Each strain was tested two times against erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, streptomycin, gentamicin, tetracycline, doxycycline, ampicillin, and cefotaxime. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined after 48 h of incubation at 30°C under microaerophilic conditions. The A. butzleri type strain DSM 8739 was used as a control. In this study, the cut-off values for Campylobacter spp. provided by EUCAST (2019) were used for erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, and tetracycline because currently no specific breakpoints are available for Aliarcobacter spp. For gentamicin, ampicillin, and cefotaxime, we used the breakpoints for Enterobacterales provided by EUCAST (2019). For streptomycin, the cut-off values for Campylobacter spp. provided by the EFSA Journal 2019 were used [European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) et al., 2019]. The bacterial strains were classified as sensitive, intermediate, or resistant.

Urease Test

For the urease test, the following ingredients of a urea broth (Merck KgaA, Darmstadt, Germany) were added to one liter of Arcobacter broth: potassium hydrogen phosphate (7.63 g/L), disodium hydrogen phosphate (9.59 g/L), urea (20.0 g/L), and phenol red (0.012 g/L). The final broth was inoculated with colony material from fresh A. butzleri cultures and incubated at 30°C for 48 h under microaerophilic conditions to increase bacterial growth. Then, the broth was further incubated at 37°C for at least 72 h. A color change from orange to pink was considered as a positive result. The urease assay was done for the 45 A. butzleri strains investigated in this study as well as for two strains (16CS0817-2 and 16CS0821-2) for which culture material was available as they were previously examined by our institute (Müller et al., 2020a). Each strain was subjected to the urease assay twice.

DNA Extraction and Whole-Genome Sequencing

DNA extraction was performed for 45 A. butzleri isolates as described previously (Müller et al., 2020a). Briefly, the DNA was extracted from fresh A. butzleri cultures using the Qiagen Genomic-tip 20/G (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). The concentration of the double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) was examined with a Qubit 3 Fluorometer using the QubitTM dsDNA HS Assay Kit (both InvitrogenTM, ThermoFischer Scientific, Berlin, Germany). The Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, United States) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions to generate a paired-end sequencing library. Whole-genome sequencing was done with an Illumina MiSeq instrument (Illumina, Inc.) generating reads of 300 base pairs (bp) in length.

Bioinformatic Analyses

The 45 genomes sequenced in this study were analyzed together with 29 European A. butzleri genomes (France = 1, UK = 1, Italy = 2, Germany = 4, and Portugal = 21) (Fanelli et al., 2019; Isidro et al., 2020; Müller et al., 2020a) and the A. butzleri reference genome (NCTC 12481T, accession: GCF_900187115.1) (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1). Those additional A. butzleri genomes were downloaded from the NCBI GenBank database (last accessed on 08.07.2020) (Benson et al., 2013). For 24 publicly available A. butzleri genomes raw sequencing reads were available and downloaded from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA, last accessed on 08.07.2020) (Leinonen et al., 2011). The raw reads together with the raw data of the 45 A. butzleri isolates sequenced herein were de novo assembled. For the analyses, we used the WGSBAC pipeline (https://gitlab.com/FLI_Bioinfo/WGSBAC) as described previously (Garcia-Soto et al., 2020; Wareth et al., 2020). WGSBAC assembled the raw data using shovill version 1.0.4 (https://github.com/tseemann/shovill) after adapter trimming with Trimmomatic (Bolger et al., 2014). The quality of all assemblies was then assessed with QUAST version 5.0.2 (Gurevich et al., 2013). The software Prokka version 1.14.5 (Seemann, 2014) in default settings was used to annotate the assembled genomes.

Table 1.

The metadata of 75 A. butzleri strains used in this study.

| WGS | Strain | BioProject | Isolation source | Year of isolation | Geographic location | Farm | Sample No. | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRR12709624 | 16CS0847-3 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2016 | Germany | A | 1 | This study |

| SRR12709623 | 17CS0824 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2017 | Germany | A | 2 | This study |

| SRR12709612 | 17CS1193-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (mulard duck) | 2017 | Germany | A | 3 | This study |

| SRR12709601 | 17CS1193-2 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (mulard duck) | 2017 | Germany | A | 3 | This study |

| SRR12709635 | 17CS1193-3 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (mulard duck) | 2017 | Germany | A | 3 | This study |

| SRR12709629 | 17CS1197 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2017 | Germany | A | 4 | This study |

| SRR12709628 | 17CS1197-2 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2017 | Germany | A | 4 | This study |

| SRR12709627 | 17CS1197-3 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2017 | Germany | A | 4 | This study |

| SRR12709626 | 17CS1198-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2017 | Germany | A | 5 | This study |

| SRR12709625 | 17CS1198-2 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2017 | Germany | A | 5 | This study |

| SRR12709622 | 17CS1198-3 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2017 | Germany | A | 5 | This study |

| SRR12709621 | 16CS0367-AR | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2016 | Germany | B | 6 | This study |

| SRR12709620 | 16CS0367-1-AR | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2016 | Germany | B | 6 | This study |

| SRR12709619 | 16CS0370-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2016 | Germany | B | 7 | This study |

| SRR12709618 | 16CS0375-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2016 | Germany | B | 8 | This study |

| SRR12709617 | 16CS0375-2 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2016 | Germany | B | 8 | This study |

| SRR12709616 | 16CS0831-1-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2016 | Germany | B | 9 | This study |

| SRR12709615 | 16CS0831-4-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2016 | Germany | B | 9 | This study |

| SRR12709614 | 17CS1200-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Pekin duck) | 2017 | Germany | B | 10 | This study |

| SRR12709613 | 17CS1201 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Pekin duck) | 2017 | Germany | B | 11 | This study |

| SRR12709611 | 17CS1205-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Pekin duck) | 2017 | Germany | B | 12 | This study |

| SRR12709610 | 17CS1205-2 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Pekin duck) | 2017 | Germany | B | 12 | This study |

| SRR12709609 | 17CS1206-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Pekin duck) | 2017 | Germany | B | 13 | This study |

| SRR12709608 | 17CS1208-3 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Pekin duck) | 2017 | Germany | B | 14 | This study |

| SRR12709607 | 17CS1167 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2017 | Germany | C | 15 | This study |

| SRR12709606 | 17CS1168 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2017 | Germany | C | 16 | This study |

| SRR12709605 | 17CS1056 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2017 | Germany | D | 17 | This study |

| SRR12709604 | 17CS1066 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2017 | Germany | D | 18 | This study |

| SRR12709603 | 17CS1067 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2017 | Germany | D | 19 | This study |

| SRR12709602 | 17CS1068-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2017 | Germany | D | 20 | This study |

| SRR12709600 | 17CS1068-2 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2017 | Germany | D | 20 | This study |

| SRR12709599 | 17CS0916-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2017 | Germany | E | 21 | This study |

| SRR12709598 | 17CS0916-2 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2017 | Germany | E | 21 | This study |

| SRR12709597 | 16CS0857-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2016 | Germany | F | 22 | This study |

| SRR12709596 | 16CS0861-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2016 | Germany | F | 23 | This study |

| SRR12709595 | 17CS1092-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2017 | Germany | F | 24 | This study |

| SRR12709594 | 17CS1092-2 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2017 | Germany | F | 24 | This study |

| SRR12709593 | 17CS1095 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2017 | Germany | F | 25 | This study |

| SRR12709637 | 16CS0815-2 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2016 | Germany | G | 26 | This study |

| SRR12709636 | 16CS0820-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2016 | Germany | G | 27 | [1], this study |

| SRR12709634 | 16CS0820-2 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2016 | Germany | G | 27 | This study |

| SRR12709633 | 16CS0823-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2016 | Germany | G | 28 | This study |

| SRR12709632 | 16CS0823-2 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2016 | Germany | G | 28 | [1], this study |

| SRR12709631 | 17CS0965-1 | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2017 | Germany | G | 29 | This study |

| SRR12709630 | 17CS0965-B | PRJNA665330 | Fecal sample (goose) | 2017 | Germany | G | 29 | This study |

| SRR10215626 | 16CS0817-2 | PRJNA575341 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2016 | Germany | G | – | This study |

| SRR10215625 | 16CS0821-2 | PRJNA575341 | Fecal sample (Muscovy duck) | 2016 | Germany | G | – | This study |

| GCF_900187115.1 | NCTC 12481 | PRJEB6403 | Diarrheic stool (human) | 1992 | USA | – | – | NA, [9]#, [10]§ |

| GCF_004283125.1 | 55 | PRJNA489574 | Mussel | 2014 | Italy | – | – | [2] |

| GCF_004283115.1 | 6V | PRJNA489609 | Clams | 2014 | Italy | – | – | [2] |

| GCF_013363865.1 | RMI | PRJNA637480 | Raw milk | 2018 | Germany | – | – | NA |

| GCF_013363855.1 | RMIII | PRJNA637480 | Raw milk | 2018 | Germany | – | – | NA |

| GCF_000215345.2 | 7h1h | PRJNA67167 | Fecal sample (beef) | 2007 | UK | – | – | [3, 6] |

| ERR3523212 | Ab_1426_2003 | PRJEB34441 | Diarrheic stool (human) | 2003 | France | – | – | [4, 6] |

| ERR3523199 | Ab_1711 | PRJEB34441 | Poultry slaughterhouse equipment surface | 2011 | Portugal | – | – | [5, 6] |

| ERR3523202 | Ab_2211 | PRJEB34441 | Slaughterhouse surface | 2011 | Portugal | – | – | [5, 6] |

| ERR3523203 | Ab_2811 | PRJEB34441 | Carcass neck skin (poultry) | 2011 | Portugal | – | – | [5, 6] |

| ERR3523197 | Ab_3711 | PRJEB34441 | Caecum (poultry) | 2011 | Portugal | – | – | [5, 6] |

| ERR3523210 | Ab_4211 | PRJEB34441 | Carcass drippings (poultry) | 2011 | Portugal | – | – | [5, 6] |

| ERR3523201 | Ab_4511 | PRJEB34441 | Carcass drippings (flock) | 2011 | Portugal | – | – | [5, 6] |

| ERR3523204 | Ab_A103 | PRJEB34441 | River water | 2016 | Portugal | – | – | [6] |

| ERR3523214 | Ab_A111 | PRJEB34441 | River water | 2016 | Portugal | – | – | [6] |

| ERR3523198 | Ab_CR1132 | PRJEB34441 | Ready-to-eat vegetables | 2016 | Portugal | – | – | [6, 7] |

| ERR3523196 | Ab_CR1143 | PRJEB34441 | Meat (poultry) | 2016 | Portugal | – | – | [6, 7] |

| ERR3523205 | Ab_CR424 | PRJEB34441 | Meat (poultry) | 2015 | Portugal | – | – | [6, 7] |

| ERR3523200 | Ab_CR461 | PRJEB34441 | Meat (fish) | 2015 | Portugal | – | – | [6, 7] |

| ERR3523213 | Ab_CR502 | PRJEB34441 | Meat (poultry) | 2015 | Portugal | – | – | [6, 7] |

| ERR3523209 | Ab_CR604 | PRJEB34441 | Meat (beef) | 2015 | Portugal | – | – | [6, 7] |

| ERR3523206 | Ab_CR641 | PRJEB34441 | Meat (poultry) | 2015 | Portugal | – | – | [6, 7] |

| ERR3523216 | Ab_CR891 | PRJEB34441 | Meat (poultry) | 2016 | Portugal | – | – | [6, 7] |

| ERR3523215 | Ab_CR892 | PRJEB34441 | Meat (poultry) | 2016 | Portugal | – | – | [6, 7] |

| ERR3523207 | Ab_DQ20dA1 | PRJEB34441 | Milk (goat) | 2015 | Portugal | – | – | [6, 8] |

| ERR3523217 | Ab_DQ31A1 | PRJEB34441 | Milk (sheep) | 2015 | Portugal | – | – | [6, 8] |

| ERR3523211 | Ab_DQ40A1 | PRJEB34441 | Dairy plant equipment surface | 2015 | Portugal | – | – | [6, 8] |

| ERR3523208 | Ab_DQ64A1 | PRJEB34441 | Dairy plant equipment surface | 2015 | Portugal | – | – | [6, 8] |

[1] - Müller et al. (2020a); [2] - Fanelli et al. (2019); [3] - Merga et al. (2013b); [4] - Ferreira et al. (2014); [5] - Ferreira et al. (2013); [6] - Isidro et al. (2020); [7] - Vicente-Martins et al. (2018); [8] - Ferreira et al. (2017); [9] - Miller et al. (2007); [10] - Miller et al. (2009); NA, not available;

antimicrobial susceptibility values and result of the urease assay were taken from reference [9];

results of the MLST analysis were taken from reference [10].

To confirm the species identity, taxonomic classification was performed using Kraken2 version 2.0.7_beta with the database Kraken2DB (Wood et al., 2019). The average nucleotide identity (ANI) was calculated using pyani version 0.2.9 (module ANIblastall) (Pritchard et al., 2016) for all A. butzleri strains (including the reference genome NCTC 12481T) in comparison to the reference genomes of A. cryaerophilus ATCC 43158T (accession: GCF_003660105.1) and A. trophiarum LMG 25534T (accession: GCF_003355515.1) as well as to the out-group genome C. jejuni subsp. jejuni NCTC 11168 (accession: GCF_000009085.1), which were downloaded from the NCBI repository. In silico DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) was done using the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) software (available at https://ggdc.dsmz.de). In this study, the recommended formula 2 was used for analysis (Meier-Kolthoff et al., 2013). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) based on the whole-genome sequences was performed using the mlst software version 2.19.0 (https://github.com/tseemann/mlst) and the PubMLST database (pubmlst.org/arcobacter; last accessed on 27.05.2020) (Jolley and Maiden, 2010). Phylogenetic analyses were performed using Roary version 3.13.0 (Page et al., 2015) as previously applied for A. butzleri (Pérez-Cataluña et al., 2018b) and Snippy version 4.3.6 (https://github.com/tseemann/snippy). The phylogenetic tree, based on the Roary output, was built using FastTree version 2.1.9 (Price et al., 2009, 2010) and visualized with iTOL version 5.6.3 (Letunic and Bork, 2007).

For further investigations, two custom-made databases specific for A. butzleri (available at https://gitlab.com/FLI_Bioinfo_pub, Müller et al., 2020a) were used to determine the presence of potential antimicrobial and heavy metal resistance genes as well as the presence of virulence-associated genes within ABRicate version 0.8.10 (https://github.com/tseemann/abricate). A gene was considered to be present with a detection value of at least 50% coverage and 75% identity. In addition, the gyrA gene, the 23S rRNA gene, the rplV gene and the rplD gene of all A. butzleri genomes were extracted and analyzed using Geneious Prime® 2019.2.3 (Kearse et al., 2012) to identify any known point mutations or amino acid changes that are known to exist in Campylobacter spp. (Perez-Boto et al., 2010; Bolinger and Kathariou, 2017; Shen et al., 2018; Elhadidy et al., 2020).

Plasmid prediction was performed for all A. butzleri strains using BLASTn (Altschul et al., 1990) and the NCBI RefSeq plasmid database (https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/release/plasmid/). With a detection value of at least 55% coverage and 85% identity, a plasmid was considered to be present.

Results and Discussion

Bacterial Strains and Whole-Genome Sequencing

Out of 188 fecal samples, 29 were positive for A. butzleri, 10 in 2016 and 19 in 2017. These were obtained from 15 geese, eight Muscovy ducks, five Pekin ducks, and one mulard duck (Table 1). Because of the different morphology of the suspected A. butzleri colonies on the culture plates, one to three single colonies were picked and processed separately. In total, 45 A. butzleri strains were identified by MALDI-TOF MS and multiplex PCR assay. Since sufficient spectra for A. butzleri were available in the database, species identification by MALDI-TOF MS (scores > 2.3) was reliable (Hänel et al., 2018). The multiplex PCR assay identified the species A. butzleri with 100% reliability (Houf et al., 2000; Levican and Figueras, 2013).

In the present study, whole-genome sequencing of 45 A. butzleri strains was performed. The Illumina sequencing yielded an average number of 0.86 million reads per strain (range: 219,906–3,042,034 reads) and an average depth of coverage of 73.9-fold (range: 23 to 176-fold). For the 45 genomes, an average N50 value of 137.0 kbp (range: 22.9–255.9 kbp) and an average of 49 contigs per strain (range: 17–191 contigs) was calculated (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sequencing statistics, assembly statistics, and annotation of 45 German A. butzleri strains.

| ID | Sequencing statistics | Assembly statistics | Annotation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing platform | Total number of reads (X1000) | Average read length (bp) | Coverage depth | Genome size | No. contigs | N50 | GC% | Total CDS | No. rRNA | No. tRNA | |

| 16CS0847-3 | Illumina MiSeq | 539.2 | 230 | 52 | 2.12 Mbp | 30 | 114,025 | 26.96 | 2,101 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS0824 | Illumina MiSeq | 917.0 | 208 | 80 | 2.19 Mbp | 35 | 135,672 | 26.92 | 2,155 | 3 | 47 |

| 17CS1193-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 368.9 | 222 | 34 | 2.23 Mbp | 20 | 201616 | 26.93 | 2,223 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS1193-2 | Illumina MiSeq | 554.0 | 233 | 54 | 2.23 Mbp | 17 | 237,465 | 26.93 | 2,223 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS1193-3 | Illumina MiSeq | 473.0 | 233 | 46 | 2.19 Mbp | 22 | 209,048 | 26.89 | 2,181 | 3 | 45 |

| 17CS1197 | Illumina MiSeq | 337.4 | 219 | 31 | 2.21 Mbp | 73 | 63,178 | 27.00 | 2,216 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS1197-2 | Illumina MiSeq | 533.7 | 225 | 50 | 2.21 Mbp | 47 | 117,432 | 26.99 | 2,224 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS1197-3 | Illumina MiSeq | 823.1 | 218 | 75 | 2.21 Mbp | 47 | 105,309 | 26.99 | 2,225 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS1198-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 885.7 | 245 | 91 | 2.16 Mbp | 35 | 181,112 | 26.90 | 2,164 | 3 | 45 |

| 17CS1198-2 | Illumina MiSeq | 910.2 | 217 | 83 | 2.16 Mbp | 35 | 181,142 | 26.90 | 2,166 | 3 | 45 |

| 17CS1198-3 | Illumina MiSeq | 789.5 | 209 | 69 | 2.16 Mbp | 36 | 165,442 | 26.90 | 2,166 | 3 | 46 |

| 16CS0367-AR | Illumina MiSeq | 1,001.3 | 237 | 99 | 2.19 Mbp | 79 | 54,432 | 26.96 | 2,204 | 3 | 46 |

| 16CS0367-1-AR | Illumina MiSeq | 219.9 | 257 | 23 | 2.20 Mbp | 25 | 251,305 | 26.94 | 2,214 | 3 | 45 |

| 16CS0370-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 1,038.6 | 224 | 97 | 2.20 Mbp | 25 | 251,305 | 26.94 | 2,213 | 3 | 45 |

| 16CS0375-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 630.7 | 259 | 68 | 2.20Mbp | 26 | 251,306 | 26.94 | 2,213 | 3 | 46 |

| 16CS0375-2 | Illumina MiSeq | 1,009.2 | 215 | 91 | 2.20 Mbp | 36 | 137,063 | 26.94 | 2,214 | 3 | 46 |

| 16CS0831-1-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 1,566.2 | 173 | 113 | 2.20 Mbp | 34 | 157,075 | 26.94 | 2,211 | 3 | 46 |

| 16CS0831-4-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 759.8 | 231 | 73 | 2.26 Mbp | 24 | 170,136 | 26.91 | 2,255 | 3 | 47 |

| 17CS1200-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 792.7 | 235 | 78 | 2.12 Mbp | 31 | 186,556 | 26.95 | 2,122 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS1201 | Illumina MiSeq | 1,015.7 | 210 | 89 | 2.12 Mbp | 34 | 157,092 | 26.95 | 2,122 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS1205-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 315.2 | 202 | 26 | 2.24 Mbp | 61 | 81,235 | 27.06 | 2,311 | 3 | 47 |

| 17CS1205-2 | Illumina MiSeq | 823.7 | 222 | 76 | 2.24 Mbp | 42 | 130,656 | 26.88 | 2,316 | 3 | 47 |

| 17CS1206-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 903.2 | 214 | 81 | 2.24 Mbp | 53 | 103,432 | 26.88 | 2,315 | 3 | 47 |

| 17CS1208-3 | Illumina MiSeq | 333.4 | 209 | 29 | 2.24 Mbp | 64 | 117,355 | 26.89 | 2,311 | 3 | 47 |

| 17CS1167 | Illumina MiSeq | 451.7 | 232 | 44 | 2.21 Mbp | 31 | 117,108 | 26.91 | 2,170 | 3 | 45 |

| 17CS1168 | Illumina MiSeq | 1,422.1 | 246 | 147 | 2.17 Mbp | 40 | 103,522 | 26.92 | 2,143 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS1056 | Illumina MiSeq | 279.2 | 208 | 24 | 2.19 Mbp | 191 | 22,951 | 26.99 | 2,167 | 3 | 45 |

| 17CS1066 | Illumina MiSeq | 459.5 | 265 | 51 | 2.21 Mbp | 71 | 66,964 | 26.93 | 2,158 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS1067 | Illumina MiSeq | 410.9 | 241 | 41 | 2.21 Mbp | 102 | 38,333 | 26.93 | 2,160 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS1068-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 1,215.5 | 217 | 110 | 2.21 Mbp | 29 | 160,528 | 26.91 | 2,170 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS1068-2 | Illumina MiSeq | 368.6 | 201 | 31 | 2.21 Mbp | 105 | 32,597 | 26.94 | 2,148 | 3 | 45 |

| 17CS0916-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 1,019.0 | 221 | 94 | 2.03 Mbp | 24 | 204,435 | 27.07 | 2,066 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS0916-2 | Illumina MiSeq | 2,003.3 | 210 | 176 | 2.03 Mbp | 25 | 204,435 | 27.07 | 2,066 | 3 | 46 |

| 16CS0857-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 812.9 | 234 | 80 | 2.06 Mbp | 37 | 168,312 | 26.99 | 2,082 | 3 | 46 |

| 16CS0861-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 2,967.4 | 124 | 154 | 2.18 Mbp | 64 | 69,382 | 26.92 | 2,149 | 3 | 53 |

| 17CS1092-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 860.1 | 211 | 76 | 2.15 Mbp | 44 | 111,096 | 27.07 | 2,177 | 3 | 45 |

| 17CS1092-2 | Illumina MiSeq | 1,008.8 | 204 | 86 | 2.15 Mbp | 46 | 102,709 | 27.07 | 2,174 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS1095 | Illumina MiSeq | 818.2 | 213 | 73 | 2.11 Mbp | 48 | 117,56 | 27.10 | 2,127 | 3 | 46 |

| 16CS0815-2 | Illumina MiSeq | 841.5 | 228 | 80 | 2.19 Mbp | 27 | 154,166 | 26.86 | 2,191 | 3 | 46 |

| 16CS0820-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 1,353.3 | 179 | 101 | 2.12 Mbp | 21 | 18,643 | 26.98 | 2,117 | 3 | 45 |

| 16CS0820-2 | Illumina MiSeq | 1,178.6 | 200 | 99 | 2.12 Mbp | 22 | 199,264 | 27.05 | 2,124 | 3 | 46 |

| 16CS0823-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 572.6 | 226 | 54 | 2.12 Mbp | 23 | 255,949 | 27.05 | 2,122 | 3 | 46 |

| 16CS0823-2 | Illumina MiSeq | 563.8 | 229 | 54 | 2.13 Mbp | 35 | 135,934 | 27.04 | 2,142 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS0965-1 | Illumina MiSeq | 849.5 | 218 | 77 | 2.43 Mbp | 60 | 95,695 | 26.84 | 2,493 | 3 | 46 |

| 17CS0965-B | Illumina MiSeq | 327.8 | 227 | 31 | 2.18 Mbp | 147 | 26,561 | 26.99 | 2,166 | 3 | 46 |

Taxonomic Classification of A. butzleri From Germany

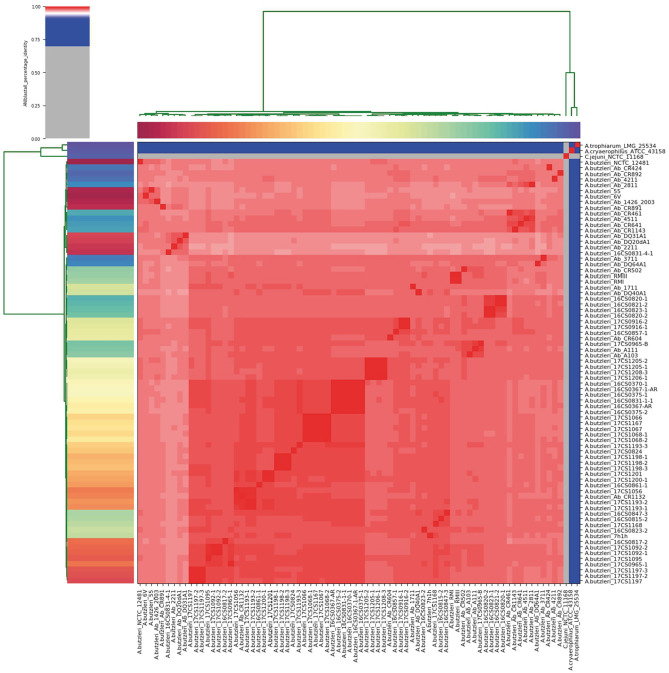

The German A. butzleri strains sequenced herein were taxonomically classified at species level, based on their reads, with an average of 89.9% (range: 72.2–94.7%) as A. butzleri using the bioinformatic tool Kraken2. To confirm this result, ANI was calculated between each genome pair based on the whole-genome sequences. The analysis showed that the German A. butzleri strains were highly similar (>95%) to the other European A. butzleri strains used in this study, confirming that those genomes belong to the same species (Goris et al., 2007; Richter and Rossello-Mora, 2009) (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 2). All A. butzleri strains (n = 74) had an average pairwise ANI value of 97.9% (range: 96.75 to 100.0%) and shared a mean nucleotide identity of 97.5% (range: 97.15 to 97.82%) with the A. butzleri reference genome NCTC 12481T. The closest relative for all 74 A. butzleri genomes was A. cryaerophilus ATCC 43158T with a mean ANI value of 78.09%. Interestingly, all A. butzleri strains were also closely related to A. trophiarum LMG 25534T (ANI of 77.22%). The analysis also showed that A. butzleri genomes had less than 67% nucleotide identity with C. jejuni subsp. jejuni NCTC 11168. Additionally, an in silico DDH analysis was performed, revealing DDH values above 76% when comparing all 74 A. butzleri strains with the reference genome NCTC 12481T (Supplementary Table 3). The recommended standard for delineating distinct species is a DDH threshold of 70% (Wayne et al., 1987; On et al., 2017). C. jejuni subsp. jejuni NCTC 11168, A. cryaerophilus ATCC 43158T, and A. trophiarum LMG 25534T do not belong to the species A. butzleri due to their low DDH values (21.80, 21.70, and 20.90%, respectively). The DDH results supported the results of the ANI analysis because the recommended DDH cut-off value corresponds very well to an ANI value of 95% (Goris et al., 2007; Richter and Rossello-Mora, 2009). Therefore, we concluded that the species of the newly sequenced German strains had been correctly identified as A. butzleri.

Figure 1.

Results of the ANI analysis. The cells in the heatmap corresponding to an ANI value of 95% and above are colored in red, indicating that the associated strains belong to the same species. Strains that do not belong to the same species are colored in blue. The dendrograms (above and on the left side), representing hierarchical clustering of the analysis results in two dimensions, were constructed by the simple linkage of the ANI percentage identities, and correspond to the results of the clustering of the ANI values between the used strains.

Phylogenetic Relatedness of the German A. butzleri Strains

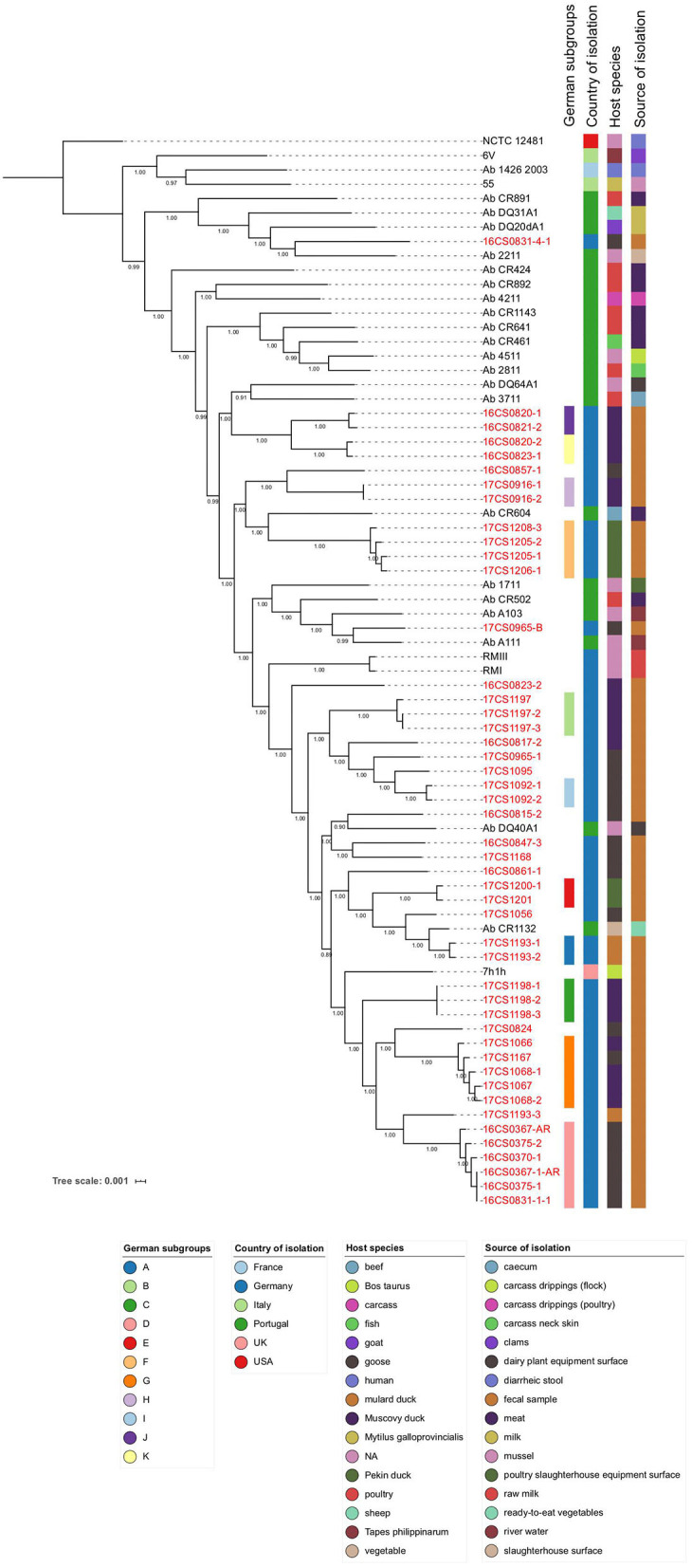

Figure 2 visualizes the phylogenetic tree based on the core genome alignment (including all A. butzleri genomes) done by Roary, which has been used before for this species (Pérez-Cataluña et al., 2018b). Most of the tree branches present high bootstrap values (average: 0.97; range: 0.89–1.00). The identified core genome consists of 1,295 genes corresponding to a size of ~1.18 Mbp, which represents half of the average A. butzleri genome. We observed that after adding about 50 genomes, the size of the core genome did not decrease any further (data not shown). The A. butzleri accessory genome comprised 10,435 genes. These findings lead to the conclusion that A. butzleri harbors an open pan-genome with a total of 11,730 genes. This result is comparable to a previous study (Isidro et al., 2020).

Figure 2.

Core-genome based phylogenetic tree involving 75 A. butzleri strains with associated metadata. All 47 German A. butzleri strains from our collection are highlighted in red. Of those, 33 strains formed 11 subgroups (A–K). Bootstrap values are depicted on the branches.

The core genome SNP analysis revealed that the mean pairwise genetic distance between our German A. butzleri isolates (n = 47) was 10,923 SNPs (range: 0–19,930 SNPs) (Supplementary Table 4). While the majority of our whole-genome sequences has sufficient coverage (>30-fold), four strains (16CS0367-1-AR, 17CS1056, 17CS1205-1, 17CS1208-3) have low coverage (23 to 29-fold). This might be an explanation for the differences between the observed SNP-inferred phylogeny and the epidemiology. Recombination might lead to false-positive SNPs but according to Isidro et al. (2020), they do not affect the phylogeny of A. butzleri. However, the distances between the genomes are reduced by 30% (Isidro et al., 2020). Thirty-three German strains could be grouped into 11 subgroups (A to K) (Figure 2). In those groups, the individual strains, which had been isolated from a single sample or multiple samples collected in the same water poultry farm, were less than 50 SNPs apart. The remaining German strains (n = 14) could not be assigned to any subgroup. Subgroup G included isolates (n = 5) that were recovered from fecal samples collected from two different farms in 2017, four from farm D (four samples from ducks), and one from farm C (one sample from a goose). Those isolates were distant to each other by less than 12 SNPs (Supplementary Table 4). The finding of highly similar strains in two different farms may indicate a possible epidemiological relatedness between them. We speculate that this could be due to a common source of animals or personnel. A fifth sample from farm D was collected from a goose in 2017. But the isolate 17CS1056 retrieved from this sample did not group with the other isolates from farm D, which could be due to the low coverage of the whole-genome sequence of this isolate or due to genetic diversity. In five subgroups (A, B, C, H, and I) the isolates were retrieved from the same sample and were less than or equal to 2 SNPs distant from each other, indicating a clonal-relatedness. Although the remaining 5 subgroups (D, E, F, J, and K) included isolates of two or more samples from the same farm, they were distant to each other by less than 35 SNPs. A possible explanation for this result could be that there is a clone circulating in the water poultry farm's herd. Subgroup A contains two isolates (17CS1193-1 and 17CS1193-2) retrieved from a fecal sample of a duck that was collected from farm A in 2017. The third isolate of this sample, 17CS1193-3, is distant by more than 8,500 SNPs to the two strains of subgroup A. This finding might be due to the presence of two A. butzleri strains which are not clonally related. High divergence was also observed in two isolates (16CS0831-1-1, 16CS0831-4-1) from farm B, isolated in 2016 from a goose; a distance of 19,445 SNPs was detected. The same applied for four isolates retrieved out of 2 different samples from ducks in 2016 from farm G. While the isolates 16CS0820-1 and 16CS0820-2 were distant by 6,973 SNPs, the other two isolates (16CS0823-1, 16CS0823-2) were distant by 13,490 SNPs. The same farm had been sampled once more in 2017, and from this additional sample (from a goose), two isolates were recovered. These were ~12,580 SNPs distant from each other. This phenomenon has also been described before for A. cryaerophilus isolates from German water poultry (Müller et al., 2020b).

Furthermore, the MLST analysis showed that out of 45 German A. butzleri strains sequenced herein, only four were assigned to a known sequence type (ST) (Table 3). The remaining 43 strains most likely belong to new STs. Nevertheless, most of the German A. butzleri strains assigned to a subgroup have the same MLST profile. Therefore, we hypothesize that strains with the same allelic profile also belong to the same ST. Since January 2019, the PubMLST database for Aliarcobacter is no longer curated, therefore, it was not possible to upload the sequences and assign them to new STs. The PubMLST database contains MLST data of 736 A. butzleri isolates from 18 countries. Of these, 725 A. butzleri strains were assigned to 680 different STs, showing a high genetic diversity of this species. This high genetic diversity of A. butzleri may be the reason why we could not assign 43 of the German genomes to a specific ST. In this study, the MLST results of some European strains varied from the MLST results of a previous study which is most likely due to different assembly approaches (Table 3). In fact, when the available assembly data of the European strains were used for the MLST analysis, the same alleles were identified as in the study conducted by Isidro et al. (2020). However, in some genomes (n = 10) the accurate assignment was not possible due to the presence of paralogs for the glyA and gltA loci (i.e., multiple copies in the same genome). Similar observations were made for strains of the species A. butzleri and A. cryaerophilus (Isidro et al., 2020; Müller et al., 2020b), although the paralogs found here were not identical except for the gltA locus. While developing the first MLST scheme for Aliarcobacter, Miller et al. (2009) reported the presence of two glyA loci, glyA1 and glyA2. At the end, the glyA1 locus was integrated into the scheme due to its discriminatory power. Consequently, the here identified paralogs of the glyA locus could represent the alleles of both glyA loci. This is supported by the fact that the detected alleles (1; 142) for the glyA locus of the A. butzleri reference strain NCTC 12481T are identical with the alleles identified by Miller et al. (2009). In that study, allele 1 was assigned to the glyA1 locus and allele 142 to the glyA2 locus (Miller et al., 2009). We conclude that the glyA locus is either not suitable for MLST analysis since it can lead to incorrect allele calling, or new bioinformatic approaches need to be developed to tackle this problem (Isidro et al., 2020; Müller et al., 2020b).

Table 3.

Results of the MLST analysis of 75 A. butzleri strains.

| Strain | Subgroup | aspA | atpA | glnA | gltA | glyA | pgm | tkt | ST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16CS0367-1-AR | D | 4 | 4 | 40 | 19 | 471, 534 | 194 | 158 | New |

| 16CS0367-AR | D | 4 | 4 | 40 | 19 | 471, 534 | 194 | 158 | New |

| 16CS0370-1 | D | 4 | 4 | 40 | 19 | 471, 534 | 194 | 158 | New |

| 16CS0375-1 | D | 4 | 4 | 40 | 19 | 471, 534 | 194 | 158 | New |

| 16CS0375-2 | D | 4 | 4 | 40 | 19 | 471, 534 | 194 | 158 | New |

| 16CS0815-2 | – | 182 | 4 | 40 | 136 | 413? | 211 | 87 | New |

| 16CS0817-2 | – | 177 | 39 | 40 | 123 | ~511 | 194 | 24 | New |

| 16CS0820-1 | J | 47 | 217 | 4 | 129 | ~694 | 123 | 37 | New |

| 16CS0820-2 | K | 47 | 217 | 9 | 129 | ~615 | 123 | 37 | New |

| 16CS0821-2 | J | 47 | 217 | 4 | 129 | 694? | 123 | 37 | New |

| 16CS0823-1 | K | 47 | 217 | 9 | 129 | ~632 | 123 | 37 | New |

| 16CS0823-2 | – | ~229 | 4 | 34 | 4 | 488 | 102 | 63 | New |

| 16CS0831-1-1 | D | 4 | 4 | 40 | 19 | 471, 534 | 194 | 158 | New |

| 16CS0831-4-1 | – | 81 | 69 | 26 | 66 | 182 | 124 | 86 | 205 |

| 16CS0847-3 | – | 4 | 12 | 1 | 19 | 346 | ~103 | 24 | New |

| 16CS0857-1 | – | 20 | 7 | 20 | 7 | 186 | 8 | 7 | New |

| 16CS0861-1 | – | 4 | 12 | 1 | 19 | ~418 | 213 | 160 | New |

| 17CS0824 | – | 4 | 58 | 44 | 19 | 150 | 4 | 89 | New |

| 17CS0916-1 | H | 20 | 7 | 20 | 23 | 186? | 45 | 37 | New |

| 17CS0916-2 | H | 20 | 7 | 20 | 23 | 186? | 45 | 37 | New |

| 17CS0965-1 | – | 153 | 39 | 1 | 19 | 184 | 11 | ~9 | New |

| 17CS0965-B | – | 20 | 39 | 11 | 11 | 513 | 26 | 55 | New |

| 17CS1056 | – | 37 | 133 | 44 | 12 | ~379 | 278 | 160 | New |

| 17CS1066 | G | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ~139 | 4 | 89 | New |

| 17CS1067 | G | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 89 | 17 |

| 17CS1068-1 | G | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 139 | 4 | 89 | 18 |

| 17CS1068-2 | G | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ~139 | 4 | 89 | New |

| 17CS1092-1 | I | 153 | 4 | 40 | 19 | 497? | 98 | 158 | New |

| 17CS1092-2 | I | 153 | 4 | 40 | 19 | 489? | 98 | 158 | New |

| 17CS1095 | – | 153 | 4 | 40 | 19 | 528? | 98 | 158 | New |

| 17CS1167 | G | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 139 | 4 | 89 | 18 |

| 17CS1168 | – | ~69 | 12 | 9 | 19 | 410 | 290 | 165 | New |

| 17CS1193-1 | A | 4 | 4 | 44 | 12 | 376 | 4 | 160 | New |

| 17CS1193-2 | A | 4 | 4 | 44 | 12 | 376 | 4 | 160 | New |

| 17CS1193-3 | – | 4 | 4 | 51 | 126 | 471 | 20 | 89 | New |

| 17CS1197 | B | ~15 | 4 | 40 | 19 | ~677 | 63 | 9 | New |

| 17CS1197-2 | B | ~15 | 4 | 40 | 19 | ~677 | 63 | 9 | New |

| 17CS1197-3 | B | ~15 | 4 | 40 | 19 | ~677 | 63 | 9 | New |

| 17CS1198-1 | C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 19 | 351 | 219 | 158 | New |

| 17CS1198-2 | C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 19 | 351 | 219 | 158 | New |

| 17CS1198-3 | C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 19 | 351 | 219 | 158 | New |

| 17CS1200-1 | E | 41 | 133 | 51 | 19 | 510 | 4 | 160 | New |

| 17CS1201 | E | 41 | 133 | 51 | 19 | 510 | 4 | 160 | New |

| 17CS1205-1 | F | 37 | 23 | 7 | ~165 | 659 | 26 | New | New |

| 17CS1205-2 | F | 37 | 23 | 7 | ~165 | 659 | 26 | New | New |

| 17CS1206-1 | F | 37 | 23 | 7 | ~165 | 659 | 26 | New | New |

| 17CS1208-3 | F | 37 | 23 | 7 | ~165 | 659 | 26 | New | New |

| Ab_CR1143 | – | 23 | 5 | 24 | 44 | 112 | 35 | 55 | New |

| Ab_3711 | – | 20 | 2 | 1 | ~15 | ~449 | 71 | 165 | New |

| Ab_CR1132 | – | 240 | 133 | 40 | 12 | 541 | 278 | 160 | 519 |

| Ab_1711 | – | 13 | 4 | 40 | 15,15 | ~536 (545) | 102 | 158 | New |

| Ab_CR461 | – | 5 | 5 | 24 | 27 | 80 | 62 | 20 | New |

| Ab_4511 | – | 23 | 44 | 24 | 44 | 112 | 35 | 20 | 510 |

| Ab_2211 | – | 234 | 15 | 26 | 164 | 375 | 260 | 176 | 460 |

| Ab_2811 | – | 23 | 44 | 24 | 2 | 769? (137) | 62 | 20 | New (107) |

| Ab_A103 | – | 20 | ~39 | 11 | 11 | 98 | 87 | 178 | New |

| Ab_CR424 | – | 23 | 7 | 33 | 38 | 156 (~745) | ~120 | 174 | New |

| Ab_CR641 | – | 23 | 44 | 24 | 15 | 124 | 55 | 20 | 108 |

| Ab_DQ20dA1 | – | 59 | 47 | 26 | 53 | ~205 | 88 | 60 | New |

| Ab_DQ64A1 | – | 10 | 20 | 11 | 19 | 192 | 123 (134) | 11 | New |

| Ab_CR604 | – | 26 | 22 | 4 | 44 | ~24 | 55 | 165 | New |

| Ab_4211 | – | 20 | 25 | 7 | 2 | ~595 (~465) | 32 | 2 | New |

| Ab_DQ40A1 | – | 4 | 164 | 40 | 19 | 418 (528) | 102 | 4 | New |

| Ab_1426_2003 | – | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 191 (9) | 9 | 8 | New (47) |

| Ab_CR502 | – | 20 | 39 | 11 | 15 | ~103 (~666) | ~26 | 2 | New |

| Ab_A111 | – | 20 | 12 | 11 | 19 | 112? (~692) | 127 | 88 | New |

| Ab_CR892 | – | 10 | 14 | 41 | 30 | 747? (~602) | ~263 | ~31 | New |

| Ab_CR891 | – | 21 | 22 | 21 | 24 | 48 | 27 | 25 | 94 |

| Ab_DQ31A1 | – | 55 | 45 | 26 | 48 | 113 | 85 | 59 | 172 |

| 7h1h | – | 150 | 4 | 1 | 122 | ~370 | 194 | 52 | New |

| 6V | – | 236 | 161 | 1 | 183 | 521 | 296 | 207 | 537 |

| 55 | – | 332 | 8 | 1 | 166 | 685 | 367 | 292 | 675 |

| RMIII | – | 5 | 5 | 5 | 15 | 66,176 | 11 | 10 | New |

| RMI | – | 5 | 5 | 5 | 15 | 66,176 | 11 | 10 | New |

| NCTC 12481 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1,142 | 1 | 1 | New |

The allele loci that do not agree with previous results are written in bold. The alleles identified by Isidro et al. (2020) are shown in brackets. (~ = novel full length allele similar to a known allele; ? = allele partial matches to a known allele).

In summary, our results indicate a high genetic diversity among A. butzleri strains, although the sample pool of German strains was limited to one federal state (Thuringia, Germany), water poultry as host, and a short study period (2 years). Since similar isolates were identified in geese and ducks (e.g., as in subgroup G), strain diversity within A. butzleri seems to be independent of the host species. This was also supported by the overall phylogeny, as it was not possible to identify major clusters related to the host species. The phylogenetic analysis did also not support clustering based on either the isolation source or geographical location of the genomes. Similar observations have been reported before for A. cryaerophilus (Müller et al., 2020b).

Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

The 45 German A. butzleri strains were resistant to cefotaxime (Supplementary Table 1). Resistance to cefotaxime in A. butzleri is well-known, and therefore, cefotaxime is often added to selective media to inhibit the growth of accompanying bacteria (Shah et al., 2013; Rathlavath et al., 2017; Fanelli et al., 2019; Müller et al., 2020a). None of the strains was resistant to gentamicin but 26 strains showed intermediate resistance. These findings are in line with earlier studies (Abay et al., 2012; Kayman et al., 2012; Shah et al., 2012b; Ferreira et al., 2013, 2019; Van den Abeele et al., 2016; Rathlavath et al., 2017; Fanelli et al., 2019; Isidro et al., 2020). Our data shows that gentamicin can still be used for the treatment of Aliarcobacter infections like it has been suggested before (Ramees et al., 2017; Rathlavath et al., 2017), but the increasing resistance has to be kept in mind. In our study, only two isolates (17CS0916-1, 17CS0916-2) were resistant to ciprofloxacin. This result is consistent with previous studies (Miller et al., 2007; Kayman et al., 2012; Ferreira et al., 2017; Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020), although there are studies which have reported higher resistance rates (Collado and Figueras, 2011; Shah et al., 2012b; Ferreira et al., 2013, 2019; Isidro et al., 2020). From a total of 45 A. butzleri isolates tested in this study, 32 were resistant to erythromycin, 26 to doxycycline and 20 to tetracycline. These results are in line with previous studies, but resistance to erythromycin has been described controversially (Miller et al., 2007; Abay et al., 2012; Kayman et al., 2012; Shah et al., 2012b; Van den Abeele et al., 2016; Ferreira et al., 2017; Rathlavath et al., 2017; Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020; Isidro et al., 2020). Similar resistance rates for ciprofloxacin, tetracyclines, and erythromycin have been observed for Campylobacter spp. in poultry (Nobile et al., 2013; Marotta et al., 2019). Rising resistance in Campylobacter spp. has been connected with the inappropriate use or overuse of antibiotics in animal husbandry (Endtz et al., 1991; Marotta et al., 2019). We assume, that this might also be true for tetracyclines and erythromycin and Aliarcobacter spp. as they are admitted for treatment of bacterial infections in poultry in Germany. According to existing studies A. butzleri isolates are highly resistant to ampicillin (Abay et al., 2012; Kayman et al., 2012; Shah et al., 2012b; Van den Abeele et al., 2016; Rathlavath et al., 2017; Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020). However, in this study more than half of the A. butzleri strains (n = 28) were susceptible to ampicillin in vitro. Nearly all studied strains were resistant to streptomycin (n = 39), although in previous studies A. butzleri strains were usually sensitive to streptomycin (Abay et al., 2012; Rathlavath et al., 2017; Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020). This indicates an increase in resistance. Therefore, we do not recommend the use of streptomycin for the treatment of A. butzleri infections in both veterinary and human medicine.

In previous studies, the antimicrobial susceptibility of A. butzleri has been determined with different methods e.g., disk diffusion, broth microdilution, or agar diffusion. However, according to a study conducted by Van den Abeele et al. (2016), the gradient strip method should be preferred over the disk diffusion method. Since both methods' agreement stands at only 60%, our results can be compared with those of earlier studies to a limited extent. This shows the need for a standardized method for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Aliarcobacter spp., and for the interpretation of the results as already noticed by other authors (Ferreira et al., 2016; Ramees et al., 2017; Riesenberg et al., 2017).

In silico Prediction of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes

To determine the underlying genotypic antimicrobial resistance (AMR) profile, we screened all 75 A. butzleri genomes with a custom-made database (ARCO_IBIZ_AMR) as described previously (Müller et al., 2020a). This database contains 92 putative AMR genes and 27 putative heavy metal resistance genes.

The survey revealed that all tested genomes contained an average of 80 potential antimicrobial and heavy metal resistance genes. Strain NCTC 12481T harbored most of the genes (n = 104) and strain Ab_3711 the fewest (n = 66) (Supplementary Table 5).

Out of 19 efflux pumps (EP) that have been described before for A. butzleri (Isidro et al., 2020), 17 EP systems were found in the A. butzleri genomes tested in this study. The two missing efflux pump systems are EP18 and EP19 [both belong to the resistance-nodulation-division (RND) family]. Eight EPs were present in all genomes: (a) EP2, EP12, EP13, and EP14 [all members of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS)]; (b) EP5, EP6, and EP10 [belonging to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family]; and (c) EP8 [belongs to the small multidrug resistance (SMR) family]. This result is concordant with those of previous studies (Isidro et al., 2020; Müller et al., 2020a). The remaining nine EPs belong to the ABC (EP3), RND (EP4, EP7, EP11, EP15, EP16), and MFS families (EP9, EP17) and were present in 16 A. butzleri genomes. These findings showed that A. butzleri harbors all major families of efflux transporters which are present in prokaryotes except for the multidrug and toxic efflux (MATE) family (Webber and Piddock, 2003). Although they are classified into different families, EPs can confer multidrug resistance as they can export a variety of different substrates (Van Bambeke et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2014; Alcalde-Rico et al., 2016). It is worth mentioning that EP5, EP6, EP8, EP9, EP12, EP13, EP14, and EP17 each consist of only one gene. Hereby, EP9, EP14, and EP17 are of particular interest. Both, EP14 and EP17, contain the same gene, the bcr gene which is associated with resistance to sulfonamides and bicyclomycin in Escherichia coli (E. coli) (Nichols and Guay, 1989). EP9 contains the fsr gene that confers resistance to fosmidomycin (Fanelli et al., 2020). The presence of an EP does not necessarily mean that resistance to a particular antibiotic is also present; the resistance rather depends on the expression level of the EP (Alcalde-Rico et al., 2016).

Type 1 secretion systems (T1SS), which are responsible for the transport of unfolded substrates across the inner and outer membrane, are usually found in Gram-negative bacteria (Green and Mecsas, 2016). The putative T1SS described for A. butzleri (Isidro et al., 2020), was only present in six strains.

The analysis of potential antibiotic determinants revealed that all tested genomes carried additional putative multidrug export ATP-binding/permease proteins (RM4018p_11130, ybiT1, ylmA, macB1) and parts of putative EP systems (acrB, tolC). The outer membrane protein gene, oprF3, and the putative multidrug export ATP-binding/permease protein, RM4018p_04700, were also present in all A. butzleri genomes except strain 16CS0817-2.

Resistance to tetracyclines is probably due to efflux pump mechanisms, ribosomal protection and enzymatic inactivation (Grossman, 2016). Although the tetA gene—encoding the tetracycline EP as described for Campylobacter spp. (Shen et al., 2018)—was present in 37 genomes, the phenotype did not correspond to the genotype as both, sensible and resistant isolates carried this gene (Table 4). However, as mentioned above, the phenotype may depend on the expression level of the EP. Ribosomal protection proteins encoded by, for example the tet(O) gene, were not present, which is not surprising as they are usually located on plasmids (Elhadidy et al., 2020). Although the plasmid prediction in this study revealed the possible presence of a known A. butzleri plasmid in seven strains (Supplementary Table 6), none of the suggested plasmid carried a potential resistance or virulence-associated gene. Therefore, A. butzleri strains either carry a hitherto unknown plasmid or harbor an unknown resistance mechanism against doxycycline and tetracycline. Further studies on this topic are needed in the near future.

Table 4.

Genotype-phenotype correlations regarding antibiotic resistance detected in this study.

| Strain | DC | tetA_gene | TET | CIP | gyrA_gene* | AMP | bla2_gene | bla3_gene | hcpC_gene | mrdA_gene | pbpB_gene | pbpF_gene | CTX | Urease assay | Urease cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16CS0847-3 | S | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS0824 | R | R | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1193-1 | S | S | S | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1193-2 | S | S | S | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1193-3 | S | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1197 | R | R | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1197-2 | R | R | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1197-3 | R | R | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1198-1 | S | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1198-2 | S | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1198-3 | S | S | S | S | R | Ø | |||||||||

| 16CS0367-AR | R | R | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 16CS0367-1-AR | R | R | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 16CS0370-1 | R | R | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 16CS0375-1 | R | R | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 16CS0375-2 | R | R | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 16CS0831-1-1 | R | R | S | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 16CS0831-4-1 | R | R | S | R | R | Ø | |||||||||

| 17CS1200-1 | S | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1201 | S | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1205-1 | S | S | S | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1205-2 | R | S | S | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1206-1 | R | S | S | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1208-3 | R | S | S | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1167 | R | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1168 | S | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1056 | S | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1066 | S | S | S | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1067 | S | S | S | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1068-1 | R | R | S | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1068-2 | R | R | S | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS0916-1 | S | R | R | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS0916-2 | R | R | R | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 16CS0857-1 | R | R | S | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 16CS0861-1 | R | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1092-1 | R | R | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1092-2 | S | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS1095 | S | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 16CS0815-2 | S | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 16CS0817-2 | S | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 16CS0820-1 | R | R | S | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 16CS0820-2 | R | R | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 16CS0821-2 | R | R | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 16CS0823-1 | R | R | S | R | R | + | |||||||||

| 16CS0823-2 | R | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS0965-1 | S | S | S | S | R | + | |||||||||

| 17CS0965-B | R | S | S | S | R | + |

The determined phenotype of the 47 German strains is presented next to the associated genotype, their presence/absence is marked by colored/ white boxes.

Presence of the mutation Thr-85-Ile.

R, resistant phenotype; S, susceptible phenotype; +, positive urease assay; Ø, negative urease assay; DC, doxycycline; TET, tetracycline; CIP, ciprofloxacin; AMP, ampicillin; CTX, cefotaxime.

In this study, five genes which might cause phenotypic resistance to cefotaxime were identified in all genomes: bla2 (putative metallo-hydrolase), hcpC (putative beta-lactamase), mrdA, pbpB, and pbpF (all penicillin-binding proteins). Penicillin-binding proteins are the target of beta-lactam antibiotics and are therefore not a resistance mechanism as such, unless they have a low affinity for beta-lactams (Macheboeuf et al., 2006; Zapun et al., 2008). As already described by Georgopapadakou (1993), resistance to beta-lactams in Gram-negative bacteria is the result of a combination of the presence and activity of beta-lactamase genes and penicillin-binding proteins as well as reduced membrane permeability. However, this would contradict the phenotype determined against ampicillin (Table 4). Isidro et al. (2020) noticed a strong correlation between the ampicillin resistance and the presence of the bla3 gene (OXA-15 beta-lactamase). This hypothesis is partly supported by the results of this study. Here, only two strains (16CS0831-1-1, 16CS0820-1) that did not carry the bla3 gene were resistant to ampicillin, and of 33 genomes carrying the bla3 gene, only four isolates (17CS1167, 16CS0820-2, Ab_CR1132, Ab_DQ64A1) were susceptible to ampicillin.

As reported previously, resistance to ciprofloxacin in Aliarcobacter spp. is due to a point mutation (C254T) in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) at position 254 of the gyrA gene (Abdelbaqi et al., 2007). This transition leads to the substitution of threonine to isoleucine (Thr-85-Ile). In this study, 11 A. butzleri genomes showed this mutation, two German strains (17CS0916-1 and 17CS0916-2) and nine Portuguese strains (Ab_1711, Ab_2811, Ab_3711, Ab_4211, Ab_A103, Ab_CR1143, Ab_CR502, Ab_CR892, and Ab_DQ20dA1). Those A. butzleri strains were also phenotypically resistant to ciprofloxacin (Table 4, Supplementary Table 1). This result is concordant with earlier studies, although higher resistance rates have been reported (Fera et al., 2003; Ferreira et al., 2013, 2017; Van den Abeele et al., 2016; Rathlavath et al., 2017; Vicente-Martins et al., 2018).

Point mutations in the 23S rRNA gene and amino acid changes in the rplD and/or rplV gene are considered to be the cause of resistance to erythromycin, as described previously for Campylobacter spp. (Alfredson and Korolik, 2007; Perez-Boto et al., 2010; Bolinger and Kathariou, 2017; Shen et al., 2018; Elhadidy et al., 2020). All used genomes were screened for modifications, but none was detected in any strain. Therefore, the resistance mechanism in A. butzleri needs to be different. In a previous study, it has been hypothesized that the protein size of the regulator TetR (RM4018p_22360), part of EP16, might correlate with the resistance to erythromycin. Truncating mutations in the tetR gene could lead to overexpression of EP16 and thus to increased excretion of erythromycin (Isidro et al., 2020). In another study, the involvement of EP3 has been discussed because it contains two macrolide export proteins (encoded by macA1 and macB2 gene) (Fanelli et al., 2019). Although the presence of those export proteins could explain the phenotype of the resistant isolates, it contradicts the phenotype of the susceptible isolates. The fact that these genes were present but not expressed, might explain the susceptible phenotype.

Furthermore, the screening for other antibiotic determinants identified additional genes in all isolates that are potentially responsible for resistance to certain antibiotics: arnB and eptA (conferring resistance to polymyxin), and rlmN (resistance to various classes of antibiotics) (Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020). The two genes, cat3 and wbpD, which confer resistance to chloramphenicol were detected in 11 and 27 genomes, respectively. While nine isolates carried three hipA genes (hipA2, hipA3, and hipA4), was the hipA1 gene only present in two and the hipA2 gene in three genomes. The hipA genes encode a serine/threonine-protein kinase—a toxic component of the type II toxin-antitoxin system—and are suspected to be involved in multidrug resistance (Schumacher et al., 2009).

In silico Prediction of Heavy Metal Resistance

The survey for heavy metal resistance genes revealed the presence of a putative cluster of genes coding for arsenic resistance in all isolates (Supplementary Table 5). This arsenic cluster consists of four genes: arsB (arsenic pump membrane protein), arsC1 (arsenate reductase), arsC2 (glutaredoxin arsenate reductase), and an arsenic resistance protein (ABU_RS02800). Simple arsenic clusters or ars operons have been reported for various Gram-negative bacteria (Ben Fekih et al., 2018). Also a putative copper cluster was found in 59 genomes, consisting of six genes: copA1 (copper-exporting P-type ATPase A), copA2 (putative copper-importing P-type ATPase A), copR (transcription activator protein), copZ (copper chaperone), csoR (copper-sensing transcriptional repressor), and cusS (sensor kinase). Furthermore, a molybdate cluster (ABC-type transport system) that has been described for E. coli and Staphylococcus carnosus, was present in all strains (Rech et al., 1995; Neubauer et al., 1999). However, the cluster was incomplete because the modC gene (encoding the cytoplasmic ATPase) was not present. Instead of the modC gene, we identified the mopA gene (regulator of modABC) which has been described in Rhodobacter capsulatus (Wiethaus et al., 2006). These findings are mostly in line with the results of previous studies (Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020).

The export mechanism for cadmium, zinc, and cobalt represented by cadA (a cadmium, zinc and cobalt transporting ATPase) and czcD (a cadmium, cobalt and zinc/H+-K+ antiporter) was present in all genomes except for Ab_3711. This is concordant with previous studies (Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020). The genes czcA and czcB, encoding cobalt-zinc-cadmium resistance proteins, were found in eight and 10 strains, respectively. Interestingly, three genes (czcR1, czcR2 and czcR3) responsible for the transcription activator protein CzcR were found in all strains, while the czcR4 gene was only present in 22 genomes.

Furthermore, all A. butzleri genomes carried four additional transporters: a mercuric transporter (merT), a zinc transporter (zntB), a putative manganese/zinc-exporting P-type ATPase (ctpC) and a magnesium and cobalt efflux protein (corC) (Fanelli et al., 2020).

The detection of heavy metal resistance clusters/transporters was expected, as the co-resistance and co-selection of AMR and heavy metal resistance, as well as the risk of simultaneous horizontal transmission between bacteria, is driven by their genetic linkage (Bengtsson-Palme and Larsson, 2015; Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020; Zhao et al., 2019). However, this also means that in an environment polluted with heavy metals, this mechanism will lead to the promotion of antibiotic resistance even without the presence of antimicrobials (Fanelli et al., 2020).

In silico Virulence Profiling

The virulence-associated genes of all 75 A. butzleri genomes were determined using the database ARCO_IBIZ_VIRULENCE (Müller et al., 2020a). This database can identify 148 virulence-associated genes, including flagellar genes (n = 36), chemotaxis system genes (n = 8), urease cluster genes (n = 6), putative capsule cluster genes (n = 7), type IV secretion system (T4SS) genes (n = 55), lipid A cluster genes (n = 12), and other virulence determinants (n = 24) described in earlier studies (Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020; Isidro et al., 2020; Müller et al., 2020a). The analysis showed that all investigated genomes carried an average of 78 putative virulence-associated genes (Supplementary Table 7). While strain 17CS0965-1 had most of the genes (n = 87), strains Ab_2811 and Ab_A103 had the fewest (n = 71).

The detection of virulence-associated genes was first reported in the context of the description of the complete genome sequence of A. butzleri RM4018 (Miller et al., 2007). In that study, Miller and his colleagues discovered homologs of the virulence genes cadF, ciaB, cj1349, mviN, pldA, and tlyA of C. jejuni as well as four other virulence determinants (irgA, iroE, hecA, hecB) in A. butzleri RM4018 (Miller et al., 2007). Of these virulence-associated genes, the following genes associated with cell adhesion and invasion were present in all 75 genomes: ciaB (host cell invasion protein), oprF2 (fibronectin-binding protein), cj1349 (fibronectin-binding protein), murJ (integral membrane protein of murein biosynthesis), pldA (outer membrane phospholipase A), tlyA (hemolysin), and additionally degP (chaperone involved in adhesion folding; Isidro et al., 2020). These results are largely consistent with those of previous studies (Douidah et al., 2012; Karadas et al., 2013; Rathlavath et al., 2017; Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020; Parisi et al., 2019; Isidro et al., 2020). The virulence determinants cirA1 and besA, which have been associated with the uropathogenicity in E. coli, were detected in 11 and 57 genomes, respectively. This is also consistent with earlier studies, as both genes are found less frequently in A. butzleri strains (Miller et al., 2007; Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020; Isidro et al., 2020). Three additional cirA genes (cirA2, cirA3, cirA4) were identified in some genomes. While cirA2 and cirA4 had the same annotation made by Prokka as cirA1—colicin I receptor—suggesting that both may be involved in iron uptake (Griggs et al., 1987), the cirA3 gene represents the former cfrB gene, which is involved in iron absorption (Isidro et al., 2020). The fur gene, which regulates the ferric uptake, was found in all tested genomes (Griggs et al., 1987; Isidro et al., 2020). According to existing studies, the genes cdiA (filamentous hemagglutinin) and shlB (hemolysin transporter protein) are rarely found. However, there are no consistent data on the presence of shlB (Douidah et al., 2012; Karadas et al., 2013; Rathlavath et al., 2017; Fanelli et al., 2019, 2020; Isidro et al., 2020). This is supported by the results of our study since cdiA was found in only two genomes (NCTC 12481T, Ab_DQ20dA1) and shlB in 11 genomes, respectively.

A. butzleri is a motile bacterium due to the polar flagellum. Therefore, the presence of flagellar genes was expected. All 36 flagellar genes were present in 62 genomes. Among the remaining 13 genomes, the flaA and flaB genes (both coding for flagellin) were absent in seven genomes, while in six genomes, only the flaA gene was missing. Similar results have been reported in previous studies (Fanelli et al., 2019; Isidro et al., 2020). The absence of both fla genes could have consequences for the assembly and/or function of the flagellum (Isidro et al., 2020).

Each of the 75 tested genomes contained a complete chemotaxis system. This is consistent with the results of earlier studies (Miller et al., 2007; Isidro et al., 2020). Of the two chemotaxis-associated genes, the luxS gene was present in all genomes, while the ccp gene was detected in only four genomes (Isidro et al., 2020).

The complete urease cluster was detected in 59 A. butzleri genomes. Forty-seven German A. butzleri isolates (45 strains from this study and two strains from a previous study of the authors; Müller et al., 2020a) underwent a functional urease test. The assay revealed that 45 strains were urease-positive. The urease-negative phenotype of strain 16CS0831-4-1 was consistent with the genotype (Table 4) because of the absence of the urease cluster in this strain. While the urease cluster was present in strain 17CS1198-3, the urease assay of this strain was negative. A detailed examination of the urease cluster of this isolate showed several changes in the amino acid sequence of the ureE gene (encoding the urease accessory protein) which could justify the observed discrepancy. Although 17CS0965-B did not carry the urease cluster, this strain was phenotypically positive. So far, we do not have a sufficient explanation for this finding. Overall, these results are concordant with previous results (Isidro et al., 2020). Consequently, we hypothesize that there is a correlation between the occurrence of the urease cluster and the urease-positive phenotype. While the ability of A. butzleri to metabolize urea is well-known (Miller et al., 2007), the presence of the urease enzyme may also be a threat to a potential host. Due to the degradation of urea to ammonium and carbon dioxide, A. butzleri might be able to survive in an acidic environment as observed for H. pylori (Gupta et al., 2019).

As part of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an endotoxin in Gram-negative bacteria, lipid A is recognized by the innate immune system and can trigger a strong immune response in humans and animals (Emiola et al., 2014). Therefore, it should be considered as an important virulence factor. We highlight the detection of a complete putative lipid A cluster in all 75 A. butzleri genomes. The putative lipid A cluster contains eight genes that are necessary for the biosynthesis of lipid A: lpxA, lpxB, lpxC, lpxD, lpxH, lpxK, lpxP, and waaA (Opiyo et al., 2010; Emiola et al., 2014; Steimle et al., 2016). Although a ninth gene, the lpxM gene (encoding myristoyltransferase), is described, its presence is usually not essential (Raetz et al., 2009; Emiola et al., 2014; Steimle et al., 2016). The presence of the lpxP gene (a paralogue of lpxL) in all genomes could explain the adaptation of growth to low temperatures and the survival of A. butzleri outside a host because the palmitoleolytransferase encoded by the lpxP gene is induced by low temperatures (Carty et al., 1999; Opiyo et al., 2010). Previous studies reported that some Gram-negative bacteria have the ability to change their lipid A structure (Ernst et al., 2001; Ramachandran, 2014; Steimle et al., 2016). These changes are regulated by a two-component system called PhoP-PhoQ and can lead, for example, to increased resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides and reduced receptor recognition (Ramachandran, 2014). Two genomes, NCTC 12481T and 6V, carried the two-component system consisting of three phoP genes (phoP1, phoP2, and phoP3) and the phoQ gene. While the PhoP-PhoQ system was detected in four strains (16CS0831-4-1, Ab_2211, Ab_DQ20dA1, and Ab_DQ31A1) without the phoP2 gene, phoP3, and phoQ were the only genes found in 17CS0965-1. Since no data were available in the current literature on how many phoP genes are necessary for the functionality of the PhoP-PhoQ system, it remains unclear if these seven strains might be able to modify their lipid A structure. All the other genomes had at least one phoP gene (phoP3) but no phoQ gene, suggesting that the two-component system was not functional. These A. butzleri strains were therefore either unable to modify their lipid A structure or used a hitherto unknown mechanism.

In this study, the genes coding for heptosyltransferases I and II, namely rfaC and rfaF, were identified in all 75 A. butzleri genomes. These heptosyltransferases are possibly responsible for the assembly and the phosphorylation of the inner-core region of the LPS (Rovetto et al., 2017; Fanelli et al., 2020). Although heptosyltransferases are not essential, their absence may affect the structure of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, and thus lead to a rough phenotype (Gronow et al., 2000).

Furthermore, the following genes were detected in all analyzed genomes: (a) cvf B (conserved virulence factor B), which is known to regulate the expression of virulence factors in Staphylococcus aureus (Matsumoto et al., 2007); (b) voc (virulence protein); and (c) virF (virulence regulator transcription activator), which has been associated with the regulation of plasmid-transmitted virulence genes in Shigella flexneri (Adler et al., 1989; Tobe et al., 1993). In contrast, the bvgS gene (virulence sensor protein) was only present in six A. butzleri strains.

Conclusion

In this study, 45 A. butzleri strains isolated from seven water poultry farms in Thuringia, Germany, were sequenced and correctly identified as Aliarcobacter butzleri.

We observed a high genetic diversity between the German A. butzleri strains, even though the isolates were limited to one federal state (Thuringia), a certain host (water poultry), and a short study period (2 years). However, the phylogenetic analysis did not support clustering based on the isolation source or geographical location of the strains.

Here, we were able to identify a comprehensive profile of potential resistance and virulence-associated genes in all investigated A. butzleri genomes. The antimicrobial genotype, however, only corresponds partially to the determined phenotype. Therefore, phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing remains necessary and important. A strong correlation was found between the presence of the gyrA mutation (Thr-85-Ile) and the phenotypic ciprofloxacin resistance, as well as between the presence of the urease cluster and urease-positive phenotype. Only a partial correlation was observed between the presence of the bla3 gene and ampicillin resistance. In addition, we would like to highlight the identification of a lipid A cluster in all studied genomes, which may allow some strains a certain amount of flexibility to the host's immune response due to the ability to modify their lipid A structure.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions generated for this study are publicly available. This data can be found here: DDBJ/ENA/GenBank; BioProject: PRJNA665330, and PRJNA575341. Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: DDBJ/ENA/GenBank; BioProject: PRJEB6403, PRJNA489574, PRJNA489609, PRJNA637480, PRJNA67167, and PRJEB34441.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the animal study because there were no experiments with animals as defined by the German Animal Protection Law (Tierschutzgesetz) and the Animal Welfare Laboratory Animal Regulation (Tierschutz-Versuchstierverordnung). Written informed consent was obtained from the owners for the participation of their animals in this study.

Author Contributions

EM and HT conceived the work. IH provided the strains and metadata. EM and IH performed antimicrobial susceptibility testing. EM performed the urease test and bioinformatic analyses and wrote the manuscript. HH, JL, and HT supervised the data interpretation. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript, read and approved the submitted manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank S. Thierbach, P. Methner, A. Hackbart, and B. Hofmann for their qualified microbiological, molecular biological and biotechnological assistance. We are also grateful to the Veterinary Health Service of Thuringia in the person of C. Ahlers for providing the samples.

Footnotes

Funding. EM is participating in a project of the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut (Antimicrobial Resistance – One Health; HJ-0005; AZ C 200 302 02/ 2018). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.617685/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abay S., Kayman T., Hizlisoy H., Aydin F. (2012). In vitro antibacterial susceptibility of Arcobacter butzleri isolated from different sources. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 74, 613–616. 10.1292/jvms.11-0487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelbaqi K., Menard A., Prouzet-Mauleon V., Bringaud F., Lehours P., Megraud F. (2007). Nucleotide sequence of the gyrA gene of Arcobacter species and characterization of human ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 49, 337–345. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00208.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler B., Sasakawa C., Tobe T., Makino S., Komatsu K., Yoshikawa M. (1989). A dual transcriptional activation system for the 230 kb plasmid genes coding for virulence-associated antigens of Shigella flexneri. Mol. Microbiol. 3, 627–635. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcalde-Rico M., Hernando-Amado S., Blanco P., Martínez J. L. (2016). Multidrug efflux pumps at the crossroad between antibiotic resistance and bacterial virulence. Front. Microbiol. 7:1483. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfredson D. A., Korolik V. (2007). Antibiotic resistance and resistance mechanisms in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 277, 123–132. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00935.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Fekih I., Zhang C., Li Y. P., Zhao Y., Alwathnani H. A., Saquib Q., et al. (2018). Distribution of arsenic resistance genes in prokaryotes. Front. Microbiol. 9:2473. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson-Palme J., Larsson D. G. J. (2015). Antibiotic resistance genes in the environment: prioritizing risks. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 396–396. 10.1038/nrmicro3399-c1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson D. A., Cavanaugh M., Clark K., Karsch-Mizrachi I., Lipman D. J., Ostell J., et al. (2013). GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D36–D42. 10.1093/nar/gks1195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A. M., Lohse M., Usadel B. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolinger H., Kathariou S. (2017). The current state of macrolide resistance in Campylobacter spp.: trends and impacts of resistance mechanisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83, e00416–e00417. 10.1128/AEM.00416-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]