Abstract

Objectives:

Geriatric palliative care approaches support deprescribing of antihypertensives in older nursing home (NH) residents with limited life expectancy and/or advanced dementia (LLE/AD) who are intensely treated for hypertension (HTN), but information on real-world deprescribing patterns in this population is limited. We examined the incidence and factors associated with antihypertensive deprescribing.

Design:

National, retrospective cohort study.

Setting and Participants:

Older Veterans with LLE/AD and HTN admitted to VA NHs in fiscal years 2009-2015 with potential overtreatment of HTN at admission, defined as receiving at least 1 antihypertensive class of medications and mean daily systolic blood pressure (SBP) <120 mm Hg.

Measures:

Deprescribing was defined as subsequent dose reduction or discontinuation of an antihypertensive for ≥7 days. Competing risk models assessed cumulative incidence and factors associated with deprescribing.

Results:

Within our sample (n = 10,574), cumulative incidence of deprescribing at 30 days was 41%. Veterans with the greatest level of overtreatment (ie, multiple antihypertensives and SBP <100 mm Hg) had an increased likelihood (hazard ratio 1.75, 95% confidence interval 1.59, 1.93) of deprescribing vs those with the lowest level of overtreatment (ie, one antihypertensive and SBP ≥100 to <120 mm Hg). Several markers of poor prognosis (ie, recent weight loss, poor appetite, dehydration, dependence for activities of daily living, pain) and later admission year were associated with increased likelihood of deprescribing, whereas cardiovascular risk factors (ie, diabetes, congestive heart failure, obesity). shortness of breath, and admission source from another NH or home/assisted living setting (vs acute hospital) were associated with decreased likelihood.

Conclusions and Implications:

Real-world deprescribing patterns of antihypertensives among NH residents with HTN and LLE/AD appear to reflect variation in recommendations for HTN treatment intensity and individualization of patient care in a population with potential overtreatment. Factors facilitating deprescribing included treatment intensity and markers of poor prognosis. Comparative effectiveness and safety studies are needed to guide clinical decisions around deprescribing and HTN management.

Keywords: Hypertension, antihypertensives, deprescribing, older adults, end-of-life, nursing homes

Medication management is an important consideration during end-of-life (EoL) care,1,2 especially addressing polypharmacy.3 Polypharmacy is associated with harm, including hospitalizations and adverse drug reactions.2,4 As such, there is great interest in supporting the deprescribing of medications (ie, deintensification, tapering or stopping drugs to improve outcomes or prevent harm3) that have questionable benefits or increased risks in patients nearing EoL, especially in nursing homes (NHs).5,6

Antihypertensives are one of the most prevalent medications prescribed among those with hypertension (HTN) and limited life expectancy and/or advanced dementia (LLE/AD).2,5,7 They are considered a target for deprescribing medications to reduce the risks associated with low blood pressure (BP), specifically postural hypotension, which contributes to falls and fractures and all-cause mortality.8

Clinical practice guidelines for HTN management vary with regard to treatment intensity recommendations for older adults with LLE/AD, because of a lack of direct evidence from studies conducted in this population.9 For example, European and American guidelines acknowledge the potentially increased risks and reduced benefits of intensive treatment in patients with LLE/AD. Yet, these stop short of recommending less intensive treatment, instead calling for individualized assessment and goals for older adults with LLE/AD. Other guidelines recommend higher BP targets and/or avoiding the use of >3 antihypertensives. Inconsistency among guidelines and inadequate direct evidence regarding outcomes of antihypertensive deprescribing to tailor care may result in real-world variability in treatment and deprescribing patterns in older NH residents with HTN at EoL.

Few observational studies have examined rates of and factors associated with antihypertensive deprescribing among older adults with HTN, with most focusing on ambulatory populations.9–11 Rates of deprescribing were low, ranging from 11% in the general NH population and 16% to 19% among ambulatory older adults.10,11 No studies have focused on the subpopulation of LLE/AD. Therefore, we sought to describe the rates of and factors associated with deprescribing antihypertensives in NH residents with LLE/AD who are potentially overtreated for HTN at admission.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study that examined antihypertensive deprescribing among residents of Veterans Affairs (VA) NHs, known as Community Living Centers (CLCs), over fiscal years (FYs) 2009-2015. CLCs provide both post-acute and long-term care. This study received institutional review board approval with a waiver of informed consent from the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System.

Data Sources

Information on episodes of VA CLC care were extracted from the VA Residential History File, which tracks Veterans across care settings using integrated VA, Medicare, and Minimum Data Set (MDS) records12,13 The VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) was used to identify use of VA health care services. Within CDW, bar code medication administration data provided documentation of all doses administered in the CLC. Medicare claims were used to identify non-VA use for Veterans with dual Medicare and VA coverage.14,15 MDS provided information on sociodemographic, environment of care, and clinical variables based on assessments conducted at CLC admission.16 As VA transitioned from MDS v2.0 to v3.0 in July 2012, we used variables that could be constructed from either version. VA Service Support Center (VSSC) files were used to obtain VA facility characteristics.17

Sample

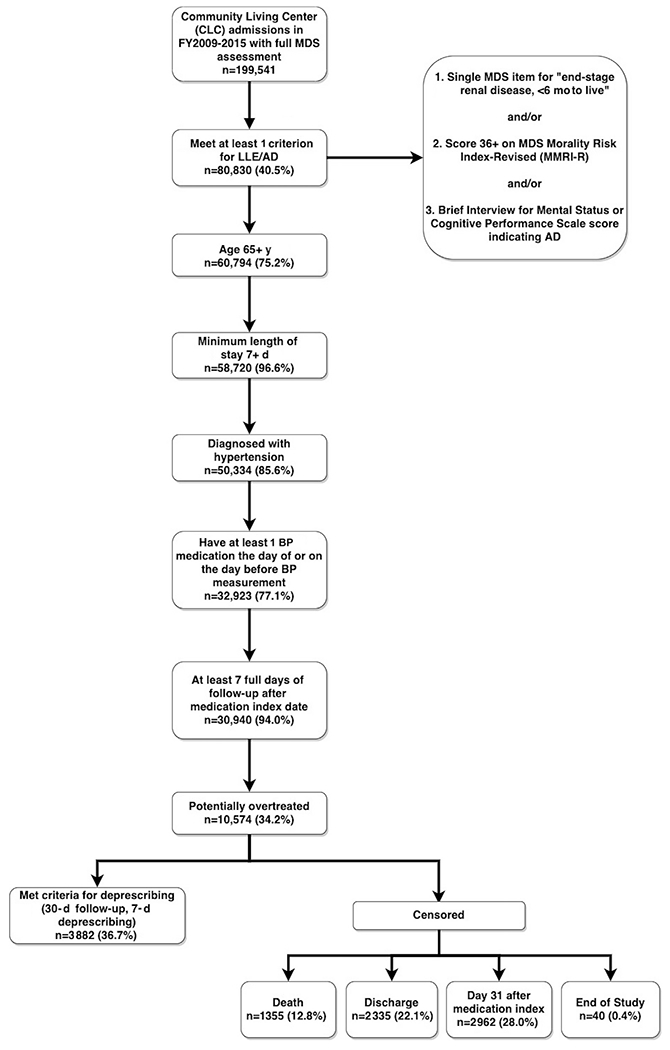

The sample included Veterans ≥65 years old admitted to CLCs for at least 7 days over FY2009-2015 with evidence of LLE/AD and potential overtreatment of HTN (Figure 1). Evidence of LLE/AD required at least 1 of the following criteria: MDS Mortality Risk Index (MMRI) score of at least 36, MDS item indicating end-stage disease or <6 months to live, or advanced dementia, defined using a score ≤7 on the Brief Interview of Mental Status20 or ≥4 on the Cognitive Performance Score 21 HTN diagnosis was based on the MDS indicator for HTN or ICD-9 codes in VA or Medicare use records 23

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of sample construction of older Veterans with limited life expectancy and/or advanced dementia and hypertension admitted to VA CLCs in FY2009-2015 with potential overtreatment for HTN. Potentially overtreated: mean daily systolic BP <120 mm Hg and receipt of at least 1 antihypertensive medication. MMRI-R, Mortality Risk Index for predicting death in the next 6 months validated in VA nursing home population.

We used a combination of BP measurements and medication classes administered on days 2-7 to identify residents who were potentially overtreated for HTN (Supplementary Figure 1). We used this time frame because the date of CLC admission (day 1) may be a partial day (transferring care). We required residents to have at least 1 valid BP value (systolic 30-305 mm Hg and diastolic 20-180 mm Hg)24 and an antihypertensive (Supplementary Table 1). To determine baseline BP, we used available systolic BP (SBP) readings on the first day in this time frame and calculated the mean SBP on that day if there were multiple values. For the baseline medication regimen, we evaluated antihypertensives administered on either the day of or day before the valid BP measurement to account for any doses that were withheld on a given day, and used the day with the greater number of antihypertensive classes (ie, medication index date). We limited the sample to residents with at least 7 days of follow-up after the medication index date to allow for sufficient time to observe deprescribing. Finally, we identified those with potential overtreatment for HTN (N = 10,574), defined as an SBP <120 mm Hg and receipt of at least 1 antihypertensive medication at baseline.10,11,25

Dependent variable

Deprescribing of antihypertensives was defined as a dose decrease (in total daily dose) or discontinuation of an antihypertensive medication, without increase or addition of another antihypertensive drug, within 30 days following the medication index date (Supplementary Figure 1).11 In primary analyses, we required the dose decrease/discontinuation to be sustained for at least 7 days to qualify as deprescribing.10 In sensitivity analyses, we extended the length of the sustained deprescribing period to 14 days. Date of deprescribing was defined as the first day of the sustained dose decrease/discontinuation. Residents were followed from the medication index date until the deprescribing date or censoring due to death, discharge, end of follow-up, or the end of the available data (ie, September 30, 2015).26 For residents who were censored and not considered deprescribed, the maximum possible calculated survival time was 30 days. In these cases, 37 days of data were used, and the censoring date was set to 7 days before the censoring event (the last 7 days of available follow-up represents immortal time attributable to observing deprescribing).26,27

Independent variables

We hypothesized that the likelihood of antihypertensive deprescribing could be influenced by the following factors: level of potential overtreatment, sociodemographics, environment of care factors, markers of poor prognosis, cardiovascular (CV) risk factors, and facility characteristics.28 We created independent variables to reflect factors within each of these categories.

We defined 4 categories for intensity of overtreatment based on number of antihypertensive classes and baseline BP as a covariate: low SBP (100 to <120 mm Hg) with 1 class, low SBP with multiple classes, very low SBP (<100 mm Hg) with 1 class, and very low SBP with multiple classes.10,11

Sociodemographic factors of sex, race or ethnicity, marital status, and age at admission were obtained from the MDS. Environment of care factors included admission source on the MDS, hospitalization in a VA or non-VA setting in the 365 days prior to admission, characteristics of the next of kin (NOK) recorded in the electronic health record, and NOK geographic proximity to the CLC.

Clinical markers of poor prognosis were included based on studies showing their association with mortality.18,19,29 Most factors were derived from the admission MDS, including advanced dementia, recent acute mental status changes, dehydration, activities of daily living (ADL) limitation,21 aggressive behavior,30 pain, infection, swallowing difficulty, recent weight loss, poor appetite, renal failure, cancer, dehydration, mechanical diet, and parenteral nutrition/feeding tube. History of serious falls and fractures was assessed using the MDS indicator for a fall within the past 180 days combined with a validated claims-based (VA or Medicare) algorithm10 to create an overall indicator for recent fall history.31,32 We captured overall number of comorbidities using the Elixhauser comorbidity index applied to VA use records and Medicare claims for the year prior to admission.33,34 Finally, although all residents in our study were required to have LLE/AD as described above, only some of these residents had their limited prognosis (LP) explicitly documented at admission, which we hypothesized may impact prescribing decisions. The resident’s LP was considered explicitly documented if there was at least 1 of the following: (1) admission to a hospice bed within the CLC; (2) MDS documentation of hospice use within the past 14 days; or (3) endorsement of the item “end-stage disease, <6 months to live” on the MDS.

Conditions contributing to CV risk included coronary artery disease, stroke/transient ischemic attack, diabetes, congestive heart failure (CHF), hyperlipidemia, venous thromboembolism, atrial fibrillation, and myocardial infarction, defined using ICD-9–based algorithms applied to VA use data and Medicare claims.23,35 Current smoking/tobacco use, height, and weight were obtained from the MDS. We then used height and weight values to calculate and categorize body mass index.36

We were interested in VA facility characteristics, given previous studies on the impact of interfacility variation in EoL care.37–39 We classified the US census region and urban influence code of each CLC40 by linking to the Area Health Resources File.41 We used data on CLC bed size; complexity level of the VA parent station with which the CLC was affiliated; and turnover rates of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, physician assistants, practical nurses, and psychologists from the Veterans Support Service Center files.17 We also included FY of admission to assess temporal patterns.

Analysis Plan

Analyses were conducted with SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.1 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC), and StataMP, version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). We first summarized descriptive statistics for all independent variables and imputed missing data using chained equations (no variables had >5% missingness).42 We also described the use of antihypertensive regimens in the overall sample and by intensity of overtreatment. We then estimated the 30-day cumulative incidence of deprescribing, accounting for the competing risk of death, and used Fine and Gray competing risk models to calculate fully adjusted subdistribution hazard ratios (HRSD’s) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association of each independent variable described above to deprescribing of antihypertensives.43 The HRSD represents the effect of the factor on the hazard of deprescribing, holding all other independent variables constant.

We conducted sensitivity analyses to examine the robustness of our primary results to alternative definitions of potential overtreatment and deprescribing: (1) redefining potential overtreatment using the lowest SBP available (vs mean) on the index BP day, as used in previous studies,10,11,44 and (2) extending the deprescribing period to 14 days (vs 7 days).25

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the 32,940 residents with LLE/AD and HTN and at least 7 days of follow-up time, 36.7% met criteria for our final sample with potentially overtreated HTN (N = 10,574) (Table 1). Most were male (98.7%) and non-Hispanic white (81.1%), with 29.7% aged ≥85 years. Many residents had multiple comorbidities (39.4% with >5) and comorbidities related to CV risk, including hyperlipidemia (64.2), CHF (50.9%), diabetes (47.4%), atrial fibrillation (22.1%), and recent stroke/transient ischemic attack (16.5%). More than a third (36.2%) had documentation of LP at admission, and 24.7% had AD. For poor prognosis markers, 44.4% had shortness of breath, 16.8% had renal failure, and 52.3% experienced a recent fall/fracture.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Veterans With Limited Life Expectancy and/or Advanced Dementia and HTN Admitted to a VA CLC in FY2009-2015 With Potential Overtreatment for HTN

| Characteristics/Risk Factors | Potentially Overtreated for HTN, n (%) (N = 10,574) |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |

| Age at admission, y | |

| 65-74 | 3502 (33.1) |

| 75-84 | 3928 (37.2) |

| ≥85 | 3144 (29.7) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 10,440 (98.7) |

| Female | 134 (1.3) |

| Race or ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 8579 (81.1) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1382 (13.1) |

| Hispanic | 371 (3.5) |

| Other race or ethnicity | 157 (1.5) |

| Missing | 85 (0.8) |

| Marital status | |

| Not married | 5845 (55.3) |

| Married | 4716 (44.6) |

| Missing | 13 (0.1) |

| Environment of care factors | |

| Living arrangement before admission | |

| Acute hospital | 7733 (73.1) |

| Home/assisted living | 2120 (20.1) |

| Nursing home | 489 (4.6) |

| Other | 231 (2.2) |

| Hospitalization in 365 d prior to admission | 8392 (79.4) |

| Next of kin relationship to the Veteran | |

| Spouse | 3924 (37.1) |

| Child | 4305 (40.7) |

| Sibling | 1195 (11.3) |

| Other relative | 510 (4.8) |

| Friend or other specified person of unknown relation | 637 (6.0) |

| Distance from next of kin zip code centroid to CLC | |

| Quartile 1: ≤12.5 miles (20.1 km) | 2550 (24.1) |

| Quartile 2: 12.5-33.9 miles (20.1-54.6 km) | 2545 (24.1) |

| Quartile 3: 33.9-93.2 miles (54.6-150 km) | 2547 (24.1) |

| Quartile 4: >93.2 miles (150 km) | 2747 (24.1) |

| Missing | 385 (3.6) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |

| Coronary artery disease | 7205 (68.1) |

| Diabetes | 5013 (47.4) |

| Congestive heart failure | 5381 (50.9) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 6792 (64.2) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 1532 (14.5) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2338 (22.1) |

| Recent myocardial infarction (past year) | 593 (5.6) |

| Recent stroke/transient ischemic attack (past year) | 1744 (16.5) |

| Current smoker | |

| No | 9401 (88.9) |

| Yes | 1014 (9.6) |

| Missing | 159 (1.5) |

| Body mass index | |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 987 (9.3) |

| Normal or healthy weight (18.5 to <25.0) | 4499 (42.6) |

| Overweight (25.0 to <30.0) | 2857 (27.0) |

| Obese (≥30) | 2012 (19.0) |

| Missing | 219 (2.1) |

| Factors indicating poor prognosis | |

| Number of Elixhauser conditions | |

| 0-1 | 763 (7.2) |

| 2-3 | 2482 (23.5) |

| 4-5 | 3159 (29.9) |

| >5 | 4170 (39.4) |

| Advanced dementia | 2608 (24.7) |

| Limited prognosis explicitly documented at admission* | 3830 (36.2) |

| Recent weight loss | 4741 (44.8) |

| Leaves food uneaten | 4575 (43.3) |

| Renal failure | 1718 (16.8) |

| Dehydration | 141 (1.3) |

| Acute change in mental status | 1043 (9.9) |

| Shortness of breath | 4696 (44.4) |

| Cancer | 4402 (41.6) |

| ADL† | |

| Independent, requires supervision, or requires limited assistance | 2827 (26.7) |

| Requires extensive assistance | 3887 (36.8) |

| Dependent or totally dependent | 3860 (36.5) |

| Aggressive behavior‡ | |

| None | 8860 (83.8) |

| Moderate | 1108 (10.5) |

| Severe | 390 (3.7) |

| Very severe | 165 (1.6) |

| Missing | 51 (0.5) |

| Presence of any pain | |

| No | 2761 (26.1) |

| Yes | 7316 (69.2) |

| Missing | 497 (4.7) |

| Presence of infection | 2850 (26.2) |

| Swallowing problem | 1872 (17.7) |

| Mechanical diet | 4189 (39.6) |

| Intravenous nutrition or feeding tube | 1101 (10.4) |

| Falls or fractures in past 180 d | |

| Yes | 5525 (52.3) |

| No | 4823 (45.6) |

| Missing | 226 (2.1) |

| Facility characteristics§ | |

| Urban influence code | |

| Large metro | 4962 (46.9) |

| Small metro | 4526 (42.8) |

| Micropolitan | 893 (8.5) |

| Noncore rural | 193 (1.8) |

| US Census region of the CLC | |

| Northeast | 1658 (15.7) |

| Midwest | 3628 (34.3) |

| South | 3331 (31.5) |

| West | 1957 (18.5) |

| Complexity level of the parent station | |

| 1a (most complex) | 4359 (41.2) |

| 1b | 1405 (13.3) |

| 1c | 1617 (15.3) |

| 2 | 1228 (11.6) |

| 3 (least complex) | 1965 (18.6) |

| Bed size of CLC | |

| >120 beds | 1778 (16.8) |

| 60-120 beds | 3842 (36.3) |

| <60 beds | 4954 (46.9) |

| Fiscal year of admission | |

| 2009 | 1497 (14.2) |

| 2010 | 1443 (13.7) |

| 2011 | 1454 (13.8) |

| 2012 | 1539 (14.6) |

| 2013 | 1579 (14.9) |

| 2014 | 1601 (15.1) |

| 2015 | 1461 (13.8) |

Limited prognosis: defined as endorsement of end-stage disease on Minimum Data Set (MDS), hospice use in the past 14 days per MDS, and/or treating specialty of hospice.

ADL: per Morris categories of dependency.

Aggressive Behavior Scale (ABS): none (ABS = 0), moderate (ABS = 1, 2), severe (ABS = 3, 4, 5), very severe (ABS > 5).

Facility characteristics not shown in table: health professional turnover rates for the CLC, categorized into quartiles of the distribution.

Antihypertensive Regimens Associated with Potential Overtreatment for HTN at Baseline: Descriptive Statistics

Among potentially overtreated Veterans, 60.5% were taking multiple antihypertensive classes (Table 2). Many had low SBP (51.9%), and 8.6% very low SBP with multiple classes. Overall, the most common classes were beta-blockers (66.9%), loop diuretics (38.3%), and alpha-1 (nonuroselective) blockers (37.3%).

Table 2.

Antihypertensive Regimens Administered on Admission to Older Veterans With Limited Life Expectancy and/or Advanced Dementia and HTN Admitted to VA CLCs in FY2009-2015 With Potential Overtreatment for HTN, Stratified by Intensity of Overtreatment

| Overall | Intensity of Overtreatment* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSBP and 1 Class | VLSBP and 1 Class | LSBP and >1 Class | VLSBP and >1 Class | ||

| Treatment administered, n (row %) | N = 10,574 | 3579 (33.8) | 600 (5.7) | 5489 (51.9) | 906 (8.6) |

| Number of antihypertensive classes used on admission (column %) | |||||

| 1 | 39.5 | 100 | 100 | – | – |

| 2 | 32.2 | – | – | 53.5 | 51.8 |

| 3 | 20.4 | – | – | 33.3 | 35.7 |

| >3 | 7.9 | – | – | 13.2 | 12.6 |

| Most common antihypertensive classes (column %) | |||||

| Beta blockers | 66.9 | 50.0 | 48.7 | 77.7 | 80.5 |

| Loop diuretics | 38.3 | 12.7 | 19.5 | 53.7 | 59.2 |

| Alpha blockers | 37.3 | 13.6 | 12.0 | 52.2 | 56.4 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 19.9 | 12.0 | 8.2 | 27.2 | 14.4 |

| ACE/ARB | 15.8 | 8.2 | 7.3 | 21.2 | 18.3 |

| Thiazide diuretics | 8.1 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 12.3 | 11.9 |

| Most common antihypertensive regimens (column %) | |||||

| Multidrug class regimens | |||||

| Beta blockers and loop diuretics | – | – | 14.2 | 13.6 | |

| ACE/ARB, beta blockers, and loop diuretics | – | – | 11.1 | 14.2 | |

| ACE/ARB, and beta blockers | – | – | 11.0 | 13.0 | |

| Beta blockers, and calcium channel blockers | – | – | 5.3 | 3.3 | |

| Alpha blockers, and beta blockers | – | – | 4.0 | 4.8 | |

| Other regimens† | 3.6 | 4.3 | 54.4 | 51.1 | |

ACE/ARB, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers; LSBP, low systolic blood pressure; VLSBP, very low systolic blood pressure.

Levels of overtreatment: LSBP defined as 100 to <120 mm Hg measured during days 2-7 of CLC stay; VLSBP defined as <100 mm Hg measured during days 2-7 of CLC stay; class = antihypertensive class.

include potassium-sparing diuretics, centrally acting agents, and other vasodilators.

Competing Risk Models: Factors Associated with Antihypertensive Deprescribing

Cumulative incidence of antihypertensive deprescribing at 30 days was 41% (95% CI 40%, 42%) (Figure 2). Statistically significant predictors of deprescribing are in Figure 3 (all predictors in Supplementary Table 2). Overall, sociodemographic factors were not significantly associated with deprescribing, except for Hispanic vs non-Hispanic white race or ethnicity (aHRSD 0.81, 95% CI 0.66, 0.99). Several environment of care factors were significantly associated with deprescribing. Admission sources of home or assisted living setting (aHRSD 0.85, 95% CI 0.78, 0.93) or NH (aHRSD 0.76, 95% CI 0.64, 0.91) were associated with decreased likelihood of deprescribing compared with acute hospital setting. Sibling designated as NOK, compared with spouse (aHRSD 1.15, 95% CI 1.01,1.30), and farther distance of NOK to the CLC were associated with greater likelihood of deprescribing.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence of antihypertensive deprescribing with 95% confidence interval bands at 30-day follow-up and 7-day deprescribing window among older Veterans with limited life expectancy and/or advanced dementia and HTN living in VA CLCs in FY2009-2015 with potential overtreatment for HTN (n = 10,574).

Fig. 3.

Sociodemographic, environment of care, CV risk, markers of poor prognosis, and facility-level factors with statistically significant (P < .05) associations with antihypertensive deprescribing among older Veterans with limited life expectancy and/or advanced dementia and HTN living in VA CLCs in FY2009-2015 with potential overtreatment for HTN, N = 10,574. Distance of NOK: between the NOK’s zip code centroid and the address of the CLC, categorized in quartiles of the distribution. ADL: activities of daily living per Morris categories of dependency (independent, requires supervision, or requires limited assistance), (requires extensive assistance), (dependent or totally dependent); VLSBP: <100 mm Hg measured during days 2-7 of CLC stay (baseline); LSBP: 100 to <120 mm Hg at baseline; class: antihypertensive class; BMI: underweight (<18.5), normal weight (18.5 to <25), overweight (25 to <30), or obese (≥30); Facility complexity: complexity level of the VA parent station with which the CLC was affiliated (1a, 1b, 1c, 2, or 3, in order of decreasing complexity). BMI, body mass index; CV, cardiovascular; LSBP, low systolic blood pressure; VLSBP, very low systolic blood pressure.

Most CV risk–related conditions were consistently associated with decreased likelihood of deprescribing, with the exception of venous thromboembolism (aHRSD 1.09). The strongest positive predictor of deprescribing was intensity of overtreatment, especially for the highest level of overtreatment (very low SBP with multiple antihypertensive classes) compared with the lowest (low SBP with a single antihypertensive class; aHRSD 2.44, 95% CI 2.16,2.75). Diabetes (aHRSD 0.92, 95% CI 0.86, 0.99), CHF (aHRSD 0.90, 95% CI 0.83, 0.96), and obesity were significantly associated with decreased likelihood of deprescribing (overweight aHRSD 0.87, 95% CI 0.81, 0.94; obese aHRSD 0.79, 95% CI 0.73, 0.85, compared to normal weight).

Poor prognosis markers were generally associated with greater likelihood of deprescribing antihypertensives, including recent weight loss (aHRSD 1.12, 95% CI 1.05,1.20), poor appetite/uneaten food (aHRSD 1.09, 95% CI 1.03, 1.15), dehydration (aHRSD 1.47, 95% CI 1.12, 1.92), dependent/total dependence with ADL compared to least dependent (aHRSD 1.12, 95% CI 1.03,1.22), and pain (aHRSD 1.12, 95% CI 1.04,1.21). Shortness of breath was the only marker significantly associated with lower likelihood of deprescribing (aHRSD 0.93, 95% CI 0.87, 0.99).

Facility complexity was associated with deprescribing, with lower complexity levels associated with decreased likelihood of deprescribing, compared to the most complex facilities [level 1b (aHRSD 0.86, 95% CI 0.74, 1.00) and 2 (aHRSD 0.81, 95% CI 0.69, 0.96) vs level 1a]. Overall, more recent years, compared to FY2009, were associated with increased likelihood of deprescribing [FY2012 (aHRSD 1.13,95% CI 1.00, 1.27); FY2014 (aHRSD 1.17, 95% CI 1.01,1.36); and FY2015 (aHRSD 1.26, 95% CI 1.08,1.46)]. Health professional turnover rates were not associated with deprescribing (data not reported).

Sensitivity Analyses

Overall, results were similar in 2 sensitivity analyses. In analyses with an extended 14-day deprescribing window (n = 8646), 30-day cumulative incidence of deprescribing decreased slightly to 35% (95% CI 34%, 36%). When potential overtreatment for HTN was redefined using the lowest SBP rather than the mean SBP, our sample size increased (n = 15,356) and resulted in a similar 30-day cumulative incidence of deprescribing (39%, 95% CI 38%, 40%). With both sensitivity analyses, factors associated with deprescribing were substantively similar within categories of predictors (Supplementary Table 2); however, using the 14-day period attenuated the magnitude of associations for some predictors of deprescribing. Also, when using the lowest daily SBP, explicit documentation of limited prognosis became a statistically significant facilitator of deprescribing.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first observational study to characterize antihypertensive-deprescribing patterns for a large, national sample of NH residents at EoL and potentially overtreated for HTN. The overall cumulative incidence of antihypertensive deprescribing at 30 days was just under 50%, suggesting inconsistency in deprescribing across residents with potential overtreatment near the EoL, potentially reflecting the lack of evidence regarding patient-centered outcomes (eg, mortality, falls, hospitalization, cognitive performance) of deintensifying antihypertensives in this population. We observed a higher incidence of deprescribing than prior observational studies conducted in potentially overtreated, non-EoL NH residents and ambulatory older adults with antihypertensive prescription use (~10%). In a systematic review, only 1 of 11 studies of inappropriate use of antihypertensives at EoL evaluated deprescribing,45 in a single-site, pre-post observational comparison.46 Future comparative effectiveness and safety studies are clearly needed to guide clinical decisions for deprescribing antihypertensives.

Intensity of treatment exhibited the strongest association with deprescribing. Markers of poor prognosis (ie, recent weight loss, poor appetite, dehydration, dependence for ADL, and pain) and later admission year were associated with increased likelihood for deprescribing. Another national study of NH residents also found that poor prognosis factors (cognitive impairment and functional impairment) were associated with potential overtreatment for HTN in residents with dementia.47 This is consistent with the geriatric palliative approach to medication management, with less intensive treatment with reduced life expectancy.48

History of recent fall and fracture was not strongly associated with antihypertensive deprescribing. NH residents with LLE/AD may be at lower risk of fall or fracture, given institutional monitoring and dependence in ADL; however, an opportunity to improve fall prevention via less intensive treatment remains for mobile residents. Documentation of LP was not strongly associated with antihypertensive deprescribing; other studies showed mixed associations, where this factor was strongly associated with less intensive antihypertensive treatment47 but not with deprescribing.10 Again, lack of associations between these factors and deprescribing can stem from the unclear clinical recommendations in this population.

Notably, CHF and atrial fibrillation were less strongly associated with deprescribing. When antihypertensives are used in the management of other CV comorbidities, the risks and benefits of deprescribing may be less clear to providers,2 which may explain this finding. The frequency of beta-blocker and loop diuretic use in our sample reflects the high degree of CV comorbidities. Use of nonuroselective alpha-1 blockers (non–first line treatment for HTN), often in combination regimens, likely reflects use for comanagement of non-CV indications. Rationales for deprescribing specific antihypertensives vs others should be explored in future research.

Other factors associated with increased likelihood of deprescribing were NH admission from an acute hospital, admission in more recent years, and relationship (sibling vs spouse) and location of the resident’s NOK. Acute hospitalizations are associated with intensification of antihypertensives during admission and at discharge among older adults.44 Thus, NH admissions represent a deprescribing opportunity to reconcile these treatment changes. Our findings with admission year may reflect a greater acceptance of deprescribing over time. Finally, our findings suggest that residents may be more likely to be deprescribed when NOK was a sibling and lived geographically farther from the NH. This finding is difficult to interpret because the NOK listed in the medical record may not be the primary surrogate decision maker. To our knowledge, no studies have examined associations between family’s physical proximity to the resident and decision making. A few studies have examined the effect of family members’ relationship on NH and EoL care decisions and report mixed findings. One study showed that spouses experienced greater burden in decisions about NH placement compared to other kin.50 In contrast, other studies found no significant associations between kinship to the patient and EoL decision making.50,51 Future studies should examine the impact of the caregiving context and relationship on deprescribing and other EoL decisions.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although our study included a large sample and many potential factors associated with deprescribing, there are several limitations. First, there are no agreed on criteria for identifying potential overtreatment of HTN at EoL. However, we stratified by low and very low SBP11 and used a combination of SBP and antihypertensive burden, also used in previous NH studies,10,49 to examine the relationships between intensity of overtreatment and deprescribing. Also, we conducted sensitivity analyses using the mean or minimum daily BP to support the robustness of our definition of overtreatment. The ideal time period for defining deprescribing is unknown, but our use of bar code medication administration data provided granular prescription information that allows for shorter periods and more closely connects changes in medications to provider decisions, compared with claims data. We used 7 days in our main analysis, which was used by a previous VA NH study.10 Results were substantively similar using a 14-day deprescribing period, with a slight decrease in the cumulative incidence of deprescribing and minimal changes to associated factors. BP frequently fluctuates; thus, longer deprescribing windows may obfuscate the relationship of deprescribing to the baseline potential overtreatment. Lastly, we did not assess patient or caregiver preferences, intentionality, or outcomes of antihypertensive deprescribing, which are important directions for future research.

Conclusions and Implications

Real-world deprescribing patterns of antihypertensives among NH residents with HTN and LLE/AD appear to reflect variation in recommendations for HTN treatment intensity in this population and individualization of patient care in the setting of limited evidence regarding patient-centered outcomes. Factors that facilitated deprescribing reflected markers of poor prognosis and more intense treatment, which are consistent with the geriatric palliative approach. CV risk factors, especially CV comorbidities managed by antihypertensives, may deter deprescribing or were not associated with action, given inadequate evidence to inform deprescribing decisions in residents with CV comorbidities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (IIR 14-306, principal investigator C.T.T.; Office of Academic Affairs Fellowship in Medication Safety & Pharmacy Outcomes, M.V., S.P.S.). J.D.N. was funded by a T32 award from the National Institute on Aging (T32AG021885). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Preliminary research as part of this study was presented as a poster at the American Society for Health-Systems Pharmacists Midyear Meeting in December 2019 in Las Vegas, NV, and has been accepted for presentation at the American Geriatrics Society Meeting in May 2020 in Long Beach, CA.

References

- 1.Morin L, Vetrano DL, Rizzuto D, et al. Choosing wisely? Measuring the burden of medications in older adults near the end of life: Nationwide, longitudinal cohort study. Am J Med 2017;130:927–936.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNeil MJ, Kamal AH, Kutner JS, et al. The burden of polypharmacy in patients near the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:178–183.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: The process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maher RL, Hanlon JT, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2014;13:57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Todd A, Husband A, Andrew I, et al. Inappropriate prescribing of preventative medication in patients with life-limiting illness: A systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017;7:113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor CA, Greenlund SF, McGuire LC, et al. Deaths from Alzheimer’s disease–United States, 1999-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66: 521–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malek MA, van Hout H, Onder G, et al. Prevalence of preventive cardiovascular medication use in nursing home residents. Room for deprescribing? The SHELTER Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:1037–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benetos A, Bulpitt CJ, Petrovic M, et al. An expert opinion from the European Society of Hypertension–European Union Geriatric Medicine Society Working Group on the management of hypertension in very old, frail subjects. Hypertension 2016;67:820–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vu M, Schleiden LJ, Harlan ML, Thorpe CT. Hypertension management in nursing homes: Review of evidence and considerations for care. Curr Hypertens Rep 2020;22:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song W, Intrator O, Lee S, Boockvar K. Antihypertensive drug deintensification and recurrent falls in long-term care. Health Serv Res 2018;53:4066–4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sussman JB, Kerr EA, Saini SD, et al. Rates of deintensification of blood pressure and glycemic medication treatment based on levels of control and life expectancy in older patients with diabetes mellitus. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175: 1942–1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Intrator O, Cai S, Miller S. The Veterans Health Administration residential history file: A resource for research and operations. Paper resented at: The 2015 HSR&D/QUERI National Conference; July 8-10, 2015; Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Intrator O, Hiris J, Berg K, et al. The Residential History File: Studying nursing home residents’ long-term care histories. Health Serv Res 2011;46:120–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hynes DM, Koelling K, Stroupe K, et al. Veterans’ access to and use of Medicare and Veterans Affairs health care. Med Care 2007;45:214–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/CMS Data. VHA directive 1153: Access to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the United States Renal Data System (USRD) Data for Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Users within the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Information Technology (IT) Systems; April 15, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Minimum Data Set 3.0 Public Reports Overview. 2012. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Computer-Data-and-Systems/Minimum-Data-Set-3-0-Public-Reports/index.html. Accessed June 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.United States Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Support Service Center Products 2019. Available at: https://vssc.med.va.gov/VSSCMainApp. Accessed June 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porock D, Parker-Oliver D, Petroski GF, Rantz M. The MDS Mortality Risk Index: The evolution of a method for predicting 6-month mortality in nursing home residents. BMC Res Notes 2010;3:200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niznik JD, Zhang S, Mor MK, et al. Adaptation and initial validation of Minimum Data Set (MDS) mortality risk index to MDS version 3.0. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018; 66:2353–2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chodosh J, Petitti DB, Elliott M, et al. Physician recognition of cognitive impairment: Evaluating the need for improvement. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52: 1051–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol 1994;49:M174–M182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saliba D, Jones M, Streim J, et al. Overview of significant changes in the Minimum Data Set for Nursing Homes Version 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13: 595–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buccaneer Computer Systems and Service Inc. Chronic Condition Data Warehouse Medicare Administrative Data User Guide; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Genes N, Chandra D, Ellis S, Baumlin K. Validating Emergency Department Vital Signs Using a Data Quality Engine for Data Warehouse. Open Med Inform J 2013;7:34–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAlister FA, Lethebe BC, Lambe C, et al. Control of glycemia and blood pressure in British adults with diabetes mellitus and subsequent therapy choices: A comparison across health states. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2018;17:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suissa S Immortal time bias in pharmacoepidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 167:492–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niznik JD, Zhao X, He M, et al. Risk for health events after deprescribing acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in nursing home residents with severe dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:699–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Springer SP, Mor MK, Sileanu FE, et al. Incidence and predictors of aspirin discontinuation in older adult veteran nursing home residents at end-of-life. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:725–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berlowitz DR, Hickey EC, Saliba D. Can administrative data identify active diagnoses for long-term care resident assessment? J Rehabil Res Dev 2010;47: 719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perlman CM, Hirdes JP. The Aggressive Behavior Scale: A new scale to measure aggression based on the Minimum Data Set. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56: 2298–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ray WA, Griffin MR, Fought RL, Adams ML. Identification of fractures from computerized Medicare files. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:703–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamblyn R, Reid T, Mayo N, et al. Using medical services claims to assess injuries in the elderly: Sensitivity of diagnostic and procedure codes for injury ascertainment. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;36:8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar A, Graham JE, Resnik L, et al. Examining the association between comorbidity indexes and functional status in hospitalized Medicare Fee-for-Service beneficiaries. Phys Ther 2016;96:232–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamariz L, Harkins T, Nair V. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying venous thromboembolism using administrative and claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21:154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. 2018. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight Accessed January 31, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ersek M, Thorpe J, Kim H, et al. Exploring end-of-life care in Veterans Affairs Community Living Centers. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:644–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levy CR, Fish R, Kramer AM. Site of death in the hospital versus nursing home of Medicare skilled nursing facility residents admitted under Medicare’s Part A benefit. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:1247–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casarett D, Pickard A, Bailey FA, et al. Do palliative consultations improve patient outcomes? J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Services. Urban influence codes. 2019. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/urban-influence-codes.aspx Accessed October 22, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Resources Health & Administration Services. Data downloads: Area Health Resources Files. Available at: https://data.hrsa.gov/data/download Accessed October 22, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 42.StataCorp. Multiple Imputation. 2013. Available at: https://www.stata.com/manuals13/mi.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anderson TS, Wray CM, Jing B, et al. Intensification of older adults’ outpatient blood pressure treatment at hospital discharge: National retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2018;362:k3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Molist Brunet N, Sevilla-Sánchez D, Amblàs Novellas J, et al. Optimizing drug therapy in patients with advanced dementia: A patient-centered approach. Eur Geriatr Med 2014;5:66–71. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morin L, Todd A, Barclay S, et al. Preventive drugs in the last year of life of older adults with cancer: Is there room for deprescribing? Cancer 2019;125: 2309–2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boockvar KS, Song W, Lee S, Intrator O. Hypertension treatment in US long-term nursing home residents with and without dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:2058–2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holmes HM, Hayley DC, Alexander GC, Sachs GA. Reconsidering medication appropriateness for patients late in life. Arch Intern Med 2006;166: 605–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benetos A, Labat C, Rossignol P, et al. Treatment with multiple blood pressure medications, achieved blood pressure, and mortality in older nursing home residents: The PARTAGE study. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:989–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boucher A, Haesebaert J, Freitas A, et al. Time to move? Factors associated with burden of care among informal caregivers of cognitively impaired older people facing housing decisions: Secondary analysis of a cluster randomized trial. BMC Geriatr 2019;19:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maust DT, Blass DM, Black BS, Rabins PV. Treatment decisions regarding hospitalization and surgery for nursing home residents with advanced dementia: The CareAD Study. Int Psychogeriatr 2008;20:406–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toles M, Song MK, Lin FC, Hanson LC. Perceptions of family decision-makers of nursing home residents with advanced dementia regarding the quality of communication around end-of-life care. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018;19: 879–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.